May 29, 2019

My Ill-Fated Career in STEM

I spend a lot of time grateful for being a parent in the age of the internet, online bullying and Insta-perverts notwithstanding, because it means I’ve not only got at my fingertips birthday party ideas, assurances in the event of weird health symptoms, and recipes whose ingredients are whatever random vegetables happen to be shrivelling in my fridge, but that I’ll never be as lost as my mother must have been on that afternoon in 1988 when I came home from school and informed her that I needed to have a science project to take to school the following day.

And so began my ill-fated career in STEM, a career that was managed by my mom, from whom I might have received my lack of proclivity in the sciences, but who also taught me everything I know about being a parent who shows up for her kid. She must have called around our subdivision and found a book of home science experiments, and somehow that night she managed to help me put together some experiment involving a bottle and a balloon that inflates. I don’t remember what the science was. I don’t suppose I ever knew. I was oblivious to a lot in 1988, not just to science, but also to life-management in general, which was underlined when I took my project to school the next day, and learned I’d gotten mixed up and the science fair was not until the following week. Which meant that I was just ahead of the game, I thought, feeling cocky, until the science fair finally arrived, and one kid had built a solar powered barbecue, and here it became clear—with my pop bottle and balloon—that perhaps this was to be a field in which I wasn’t destined to shine.

We resolved to do better the following year, or at least my mom did, coming up with an ingenious solution—and indeed, this would be the zenith of my scientific career: she found someone else to do my project altogether. It wasn’t cheating, exactly, because the whole thing was transparent. Somehow, without internet—if I can remind you—my mom managed to track down contact information for Canadian Astronaut Marc Garneau, to whom we sent a list of interview questions and a cassette tape on which he could record the answers, which he did, sending it back with photographs, stickers, and other cool things that made an excellent display. At the Science Fair, I played his answers on a tape player, and won a prize in my category, and felt pretty good about what I’d accomplished here, although I secretly wanted to build a model of the solar system like everyone else was doing, but my mom thought that was cliched.

Things would never be that good again. The following year, I began suffering from basilar artery migraines, which really only happened a handful of times, but the diagnosis meant that I could pretend to collapse on the playground and spend time in the nurses’s room being the centre of attention, and then my mom would come and pick me up and I’d go home and watch TV. The doctor I was seeing suggested I could do a project on brains and migraines, and my mom and I jumped right on board, because it meant we didn’t have to think of a project ourselves. I did some research, and must have learned something, although I remember none of it, and wrote up my project to be displayed on the three panelled wooden boards we now had explicitly for science fair purposes, held together with hinges. (Where did my mom get this board? How did she enact such miracles? Perhaps I should have done a science project on questions such as this…).

But there was a problem: I had nothing to display. Everyone else would have experiments, and the proverbial solar system models, and the kids whose dads were engineers all would have built water filtration systems in aquariums. But then my mom had an idea: what if we got a brain? An actual brain. And because she was my mom, she somehow managed to get a brain. (Where do you go to get a brain? How does she do it? Especially when you don’t have the option of online.) A cow’s brain, from a farmer, which came frozen, and I brought to school in a pie plate. But in all the trouble of acquiring a brain, my mom hadn’t thought about another scientific principle, and obviously neither had I, because I don’t think I ever thought about science at all: what happens to frozen things kept at temperatures above zero?

And so that was the year my science project was basically a melting cow’s brain, whose sight caused more than one child to vomit as she perused the science fair, and so that day my table had a layer of sawdust on the floor before it, courtesy of the janitor. It goes without saying that this was another year I didn’t win a prize at all.

We would do better then. Maybe I needed to be a more active part of the process, and do an actual experiment, so the next year I resolved that I would do some inquiry and come up with a vital scientific question that needed answering, and then I had one. Eureka. What was it? My question was: Do Plants Need Air. Which, to be fair, was a burning question that science has been trying to answer for centuries, and because my mom’s approach to parenting was to make me feel like everything I did or made or thought was excellent (and/or maybe she really did think that the jury was still out on plants and air?), she was all in.

In order for my experiment to be a success, my mom managed to procure plastic water coolers, have the bottoms sawed off them, and then we could use caulking to seal the water coolers to piece of plywood. Some of the plants would grow as usual outside the sealed coolers, which the others would grow inside the coolers which (as we failed to note or perhaps my mom was just too busy sawing plastic to consider it) were themselves filled with air. Maybe we had failed to think this through. And how would we water the plants that were in the sealed coolers? A burning question that (although we didn’t admit it to ourselves) transformed the scope of my project into one addressing the even less burning question of plants and air to this one: Do Plants Need Water? (Spoiler: yes they do.) I don’t remember precisely what the conclusions of my project were, but I know that I did not win a prize. (Also, because I had a mom that made me feel like everything I did or made or thought was excellent, I was surprised and disappointed by this.)

As a parent, this might have been the point where I packed the whole thing in, or had my child bake a cake and bring it in and declare that this was chemistry. But my mom would not give in so easily, was not that into baking, and between us we supposed we’d learned about from science fair disasters to do an experiment that was actually good. But in order to be good, preparation was necessary, so we started six months in advance—I would do a project on fast food packaging and biodegradation. (This was back when McDonalds burgers still came in Styrofoam boxes.) I remember driving around town with my mom and going to various fast good outlets to ask for wrappers, boxes and other kinds of packaging to use, and then I buried these packages in containers of soil that we kept behind our furnace with labels on the container so that we’d know which establishment had supplied each one. Sounds good, right? An actual experiment, with social relevance, and possibly could launch my career as an environmentalist? My science project was all set before the school year had even started. We had triumphed. We were awesome. We would not be defeated by the science fair, for once in our lives.

Except that turned out to be the year that the science fair was cancelled, and so the wrappers remained in our basement and rotted (or didn’t), and after that I decided to focus on the arts.

May 28, 2019

New York is Magic

I’m having trouble finding my feet again after a weekend away where everything was extreme: hot, amazing, delicious, fun, expensive, tall, far, sunny, crowded, and wonderful. A record of our adventures can be had over at Instagram, where I will continue to post New York photos into the weekend because it was summer and beautiful there, and here it’s just cold and raining (again). I didn’t spend the entire weekend on bookish pilgrimages, because I want my family to continue to want to go on vacations with me in the future, but I did spend the whole weekend reading Madeleine L’Engle’s now-obscure 1982 novel for adults The Severed Wasp (blurbed by Norman Lear, no less!) which underlined my New York experience in terrific ways, even if the novel was like a soap opera set in a church community (and how come, between L’Engle and Barbara Pym, soap operas set in church communities are my favourite kind of book?). The book was why I wanted to see The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, which was not far from where we were staying, so we went there on Friday evening. Saturday we spent walking through Chelsea, just close enough to Greenwich Village that I was channelling my two patron saints, Grace Paley and Jane Jacobs—and while I wanted to go find Faith Darwin in a tree in Washington Square, we went to Union Square instead because it was closer to The Strand Bookstore, and I can’t expect my children to traipse across the entirety of New York City on my bookish whims, because New York is very big and also then my children would hate me.

Sunday’s allusions were more musical, as I went to Strawberry Fields in Central Park, a memorial to John Lennon, which was kind of the worst kind of circus, but I suppose that was the case with everything with the Beatles in the end. I was also excited to see The Dakota, not for John Lennon because I don’t like to be morbid, BUT because it was home two to amazing literary characters, Rosemary Woodhouse in Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (well, the film version, at least) and also Laine Cummings, Stacey McGill’s best friend in The Babysitters Club, which was how I learned about many places in New York in the first place. (I wonder if they ever met in the elevator?)

On Monday, we went to Brooklyn, because I wanted to visit Books Are Magic, which everybody in our family really liked for its great aesthetics, chilled out vibe, and good books selection, plus Stuart and Iris got to read stories and lie in the floor, which is always nice at the end of a busy four days of touristing. Which was still not enough to even get a proper sense of the city and all it holds, but it was a very good start, and now we all want to go back again.

May 22, 2019

Ten Years is What

“Parent time is like fairy time but real. It is magic without pixie dust and spells. It defies physics without bending the laws of time and space. It is the truism everyone offers but no one believes until after they have children: that time will actually speed, fleet enough to leave you jet-lagged and whiplashed and racing all at once. Your tiny perfect baby nestles in your arms his first afternoon home, and then ten months later he’s off to his senior year of high school… It is so impossible yet so universally experiences that magic is the only explanation.” —Laurie Frankel, This is How It Always Is

I remember ten years ago, the weeks leading up to this weekend, a mysterious “here-be-dragons” date on the calendar. I remember sitting in the chair in my living room and the books I was reading—The Girls Who Saw Everything, by Sean Dixon, and The Children’s Book, by AS Byatt, which I binge-read all day on Monday May 25, because the book was a hardcover, big and heavy, and I was having a baby in the morning, and if I didn’t finish it before then, I knew I probably never would.

Our garden was huge and overgrown that year, and I am sure I could see the top of the forsythia from my second floor window, where I sat sitting reading these books and waiting for the day to arrive, anticipating an unknown I couldn’t properly comprehend, which was even incomprehensible in itself. One afternoon while I was sitting there, uncomfortable and enormous, a ladder appeared at the window, the housepainter I’d not been expecting, and that was day our blue house turned yellow, and now I don’t properly understand that it had ever been any other way.

The arrival of double digits is a momentous occasion in the life of a child, a kind of pseudo-legitimacy, and as a parent it is also cause for reflection. The containment of a decade is a remarkable thing, finished and solid, and all the lifetimes it has managed to hold, which was what I didn’t properly understand when Harriet was born ten years ago and my world was thoroughly rocked in a way that felt terrifying and dangerous. Because I hadn’t understood how everything would always be changing, how nothing would ever stand still again. I thought it would always be like this, those broken nights that stretched out long as my baby cried and cried, long and lonely days, and the weight of my ineptitude. The first book I read after her birth was Tom’s Midnight Garden, which seemed congruent with my own disorientation. On June 9, 2009, I wrote about the book, “The secret world wherein the clock strikes thirteen, and I feel like I’ve been there lately, up with the squalling baby who refuses to eat properly or be satiated. ‘Only the clock was left, but the clock was always there, time in, time out.'”

But those days were only ever a moment, though it didn’t feel like it at the time, and there would be moments after that were different, and I began to understand how much of being a parent is standing in the middle of a whirlwind. The person who my child would become as much of an enigma as parenthood had been in the first place, and now it’s hard to understand that that baby and the nearly ten-year-old girl who lives in my house are the actually same person. How is that even possible? Her very existence as miraculous as it has ever been, but also that she has existed in thousands of incarnations, which is weird because hasn’t it only been about ten minutes since I was sitting in that chair?

When Harriet was born, words failed me. I wrote about the greeting card verses that read so hollow, and all the cliches that didn’t work for me—the people who couldn’t imagine their lives without their children, who were “over the moon.” Although I didn’t properly understand it until after the fact, I was very unhappy and felt like I’d lost the ground beneath my feet, and was struggling to make sense of this new world that I’d arrived in—and imagining it all was permanent, that things would ever after be broken. I imagined my life without my child all the time, and missed that life—how carefree and easy it had been. I hadn’t anticipated the labour of motherhood. I’ve never had to work like that before, and it didn’t satisfy. It should have been enough, I told myself, that I had this healthy child, which I’d thought was all I wanted, but reality would prove more complicated. And complicated realities has been my salient lesson of the last ten years. There is so much I never knew before, my limits more close at hand than I’d ever imagined.

But ten years on, some things are simpler. So much isn’t, BUT the certainty with which I can say now: I can’t imagine my life without her, or her sister. I’m still mystified that they’re here at all, that we can go and make new people, and that they’re here, but also that they weren’t always. Is that even more impossible? That I had a life without them? Because I can’t fathom it, my life without the richness my children bring me. Two of the most interesting people I’ve ever met, and perhaps I’m biased because they’re mine, or else that’s just the result of knowing somebody ever since they took their first breath, and having spent year-after-year watching them grow into such remarkable human beings.

The thing about becoming a parent that is so fascinating but also excruciatingly boring for everybody else is how the most ordinary things become miraculous—pregnancy, childbirth, crawling, walking, growing, talking, reading, writing, arguing, questioning, learning, and then when they start telling you things—the moments when I feel like this is what I came for. My daughter knew all about the Winnipeg General Strike, and when I’ve got a question about insects or small mammals, she’s the one I turn to, and she’s the only person I know who read more books than I do, and her jokes are super terrible, and she’s much less proficient at magic tricks than she’d like to be, but she did a presentation in front of her whole school about climate change, and read almost all the Silver Birch Fiction picks, and she goes to Guide Camp, and she plays piano, and (most of the time) delights in the company of her sister, and she asks the best questions, and challenges me in good ways (and bad—full disclosure), and I’m just so glad she’s here, and I don’t think I will ever stop being dazzled by the fact that she’s here. Who she has been and who she is ever becoming.

May 21, 2019

Gleanings

- That’s what theoretical and ideal thinking abstracted from lived experience does, and it does it on purpose. Which…is why the anecdote has the capacity to do radical knowledge work.

- I wrote the first line of each chapter first, to get an idea of what it could be about or what might happen. It was like a poem because at that point, the novel was so distilled.

- Rage works. It takes time and numbers and a willingness to express it, but it is among the most reliable catalysts of social and political change.

- She made being human into an art.

- When I planted the clematis, I wasn’t thinking about the future.

- The placement of the park benches aren’t accidental.

- No one wants to stress out over waffles – even the Liège kind.

- I knew nothing about blogging and didn’t know how to start but I did want to write honestly about our ordinary days here at home that, in the context of the times, were surprisingly enriching and satisfying.

- Each small thing offered, in this world in my mind, is actually a really big thing.

- When people are close to us through their stories – around the dinner table, over Netflix or through blogs – it becomes impossible to put people into groups out of fear and hate, despite the horrors others may be trying to push into our ears.

- Her dual loyalties, she says, have led to an interest in translation.

- When I look at certain photographs I am immediately transported back to where it was taken.

- And this, really, in a nutshell, is why I blog.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

May 17, 2019

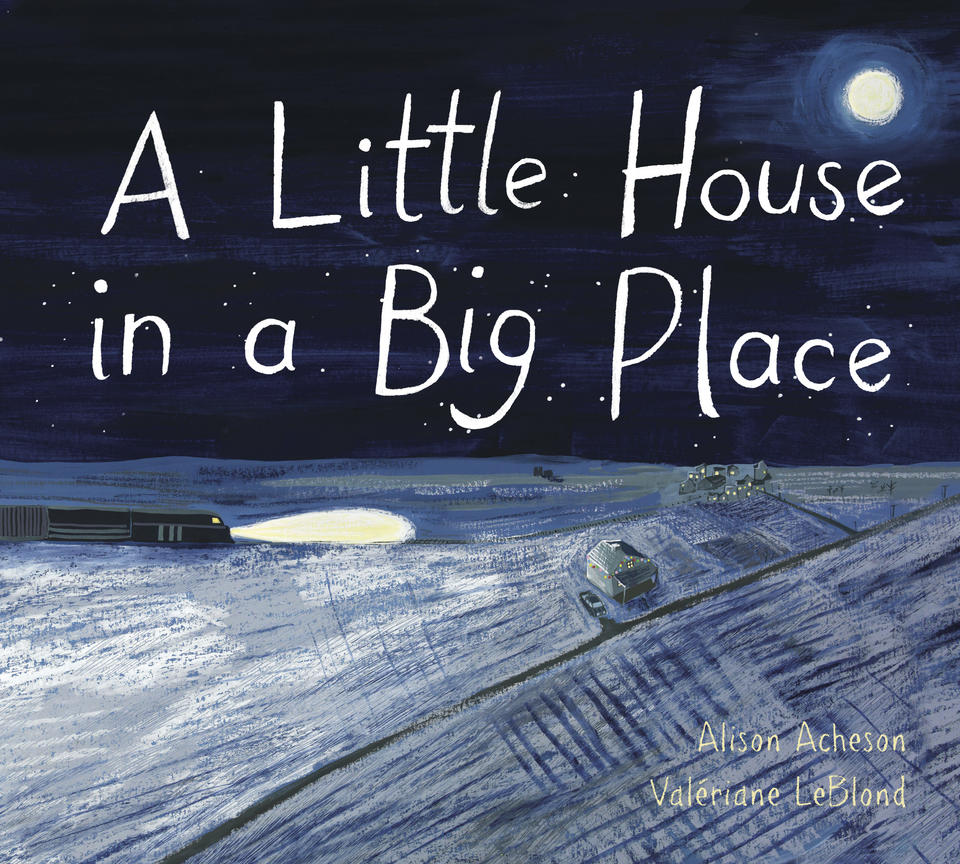

A Little House in a Big Place, by Alison Acheson and Valériane Leblond

We are in love with A Little House in a Big Place, by Alison Acheson and Valériane Leblond, a picture that manages to combine an old-fashioned sensibility with a storyline that’s utterly surprising. It’s the story of a young girl who lives in a house on the edge of a small prairie town, and every day she stands at her window and wave that the train engineer who goes past. “…[A]nd she wondered. About where he came from and where he went. And if she might go away too, someday.”

And we hear the story too from the point of view of the engineer, who waves to the girl everyday. The prairie landscape informing the narrative’s perspective: “His train came over the horizon every morning. One moment there was only sky, and the next moment there would be a dot/ that got bigger/ and bigger/ and bigger [the text getting larger with each line] and the dot would become the train.” And the train rushes away until it becomes a dot again. “But his wave and her wave together made a home in [the girl’s] heart.”

The girl wonders about the engineer, as he no doubt wonders about the girl in the window of the small house on the prairie, and they’re connected to each other, though neither knows the other at all. The girl has no idea that one day will be the train engineer’s last day on the job—but then he throws something from his window that she runs through the fields to find. And he will never know it, but the girl will carry it with her through her life.

I have a theory that this book is a secret ode to Joni Mitchell, because the end of the story finds that small girl who grew up in a prairie town living in a place far eastward, strumming her guitar in a coffee shop. But there is a universality about the story too, about the anonymous people who touch our lives, and about the places where we come from, which set us on the road towards where we’re meant to be.

May 16, 2019

Little Darlings, by Melanie Golding

If domestic noir is still your thing, but you’re finding the genre a little tired (and then some), then pick up Melanie Golding’s debut novel, Little Darlings, which blends the imperilled housewife trope with literary chops and allusions, and hearkens toward the supernatural in the most delicious way.

I read the novel in a single day over Mother’s Day weekend, which seemed entirely appropriate, this book that begins in the delirious aftermath of birth. The birth of twins, no less, and Lauren is shattered, troubled, her husband sent home and she’s left to care for her babies alone, which leaves to a terrifying nocturnal encounter—but is the whole thing just in Lauren’s mind? (And the question I always get stuck on when determining when a woman’s trouble postpartum is in her mind or otherwise—why does the difference even matter, unless you think her mind doesn’t count.)

There’s nothing like the destabilization of new motherhood, how it can reduce one to a vessel, how it realigns marriages and relationships and one’s own sense of self. Golding captures that instability incredibly in this novel as Lauren grows more and more unstable, isolated, and divorced from reality. Or is she? Could it be that Lauren is more perceptive than anyone else around her to the threat she and her sons her facing, a threat that even comes to pass. Or perhaps it does—it’s all unclear. And afterwards, Lauren is convinced that her children are not her own, that they’ve been switched with those belonging to the terrifying “river woman” who is connected to a now flooded village and lore about changelings from centuries ago.

Has Lauren lost her mind? Are the children okay? Is their mother the most real threat they’re facing? And Golding weaves these questions into another storyline involving a police detective who can’t quite let the case go after hearing a recording of Lauren’s emergency call from that night in the hospital. A detective who reminded me of Rachel Bailey from the amazing TV series Scott and Bailey, what with the dysfunctional personal life and disregard for rules and the opinions of her superiors. Turns out this Detective, Jo Harper, gave up her own child born decades before when she was a teenager, and once again the question is whether Harper’s personal experiences are guiding her intuition or whether they’re distracting her from the reality of Lauren’s case. I think we all know what the answer is…

But we don’t entirely, which I appreciate, the way that Golding complicates her story in a way that might prove frustrating to some readers who are hoping for straightforward resolutions, but the author is giving us more than that. She’s giving us problems to think on, sexist biases to consider, and also a dark and creepy story designed to unsettle.

May 16, 2019

The Arm of the Starfish and Dragons in the Water

I think it’s been about ten minutes since I last wrote an ecstatic blog post about how my decision to read Madeleine L’Engle’s Austins series was completely the best thing I’ve done in 2019; so we’re due, right? I finished up the Austin books with Troubling a Star about a month ago, and then decided to embark upon the Polly O’Keefe books, which sort of bridge the Austin and Wrinkle in Time Series. I’d tried to read An Acceptable Time as part of the Wrinkle series when I was a child, but I don’t think I finished it, and I can understand now why it might not have appealed to me, because maybe all these books are best understood in the wider context of L’Engle’s fictional universe(s).

Which is the most amazing mind-bending, time-bending universe. When I picked up Arm of the Starfish, I was actually travelling back in time myself from 1994 (when Troubling a Star was published) to 1964, when she published Arm… (I still can’t believe that this book, which includes a grown-up Meg Murry, now a rather innocuous “Mrs. O’Keefe, was written before A Swiftly Tilting Planet. The way that L’Engle wrote her books so far from the chronological order in which they can be understood to be connected to each other…) Which means that while it was remarkable to reading a novel set just before the summer depicted in A Ring of Endless Night, I was also reading a book by a less sophisticated and practiced novelist. The Arm of the Starfish was also the novel with which L’Engle followed up the smash hit A Wrinkle in Time, which no doubt was some kind of pressure.

The book was okay—it was plot driven and interesting and had all the same kinds of thematic concerns of L’Engle’s work (the nature of good and evil and how they’re connected), but it was lacking in depth and was a bit too action packed. I also found Adam Eddington a less compelling narrator than Vicky Austin, and indeed Meg Murry has not grown into a very interesting woman and my goodness, she is has more children than the Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe. But also, we’re seeing her through Adam Eddington’s eyes and teenage boys are perhaps not the greatest at seeing the marvellousness of a middle aged woman, especially when she is dripping with children. Interesting how Poly swimming with dolphins portends what happens with Vicky Austin not long after—and also I enjoy contemplating what might happen if Poly and Vicky ever met—would the universe explode?

So I wasn’t especially geared up for Dragons in the Water, published in 1976, about a boy called Simon who is on a nautical voyage to Venezuela and meets Poly (who has not yet become “Polly”) and Charles (who is Charles Wallace redux) on board, and together they have to solve a murder and also there are smugglers and art thieves. But I loved it! Simon was a great character (but then again, name a fictional orphan who isn’t) who has been raised to revere an ancestor whose story turns out to be more complicated and troubling than Simon knew. We also get a glimpse of “Mrs. O’Keefe” near the beginning of this book, and she’s a more interesting character than in the previous book.

It was also exciting to meet Mr. Theo who is travelling to hear a concert by Emily, and I met both of these characters first in The Young Unicorns (published in 1969), along with Canon Tallis, who was also in Arm of the Starfish. I love that if we tried to map out a timeline of all these books and universes and how it all fits together, my brain would turn into silly string.

As with the Austin series, the novel is informed by the time it was written in: “I know a lot of politicians nowadays, and even presidents, don’t take promises seriously and even lie under oath, but I was brought up to speak the truth,” says Simon, post-Watergate. I also read this book right after reading an article in The Guardian on a small town in Louisiana that’s one of the most toxic places to live in America because of contamination from a chemical plant, and this scenario is the same as in the novel, which is why Dr. O’Keefe has been called to Venezuela because fish are dying in a lake there where companies are drilling for oil. “Miss Leonis looked down at her feet where black sludge oozed heavily out of the lake. ‘It looks to me as though the oil industry is raping the lake….'”

And then the response: “One thing I have learned in three years at Port of Dragons is that there are no easy solutions.”

And isn’t that the truth.

May 14, 2019

We Should All be Activists

I am not an activist.

I remember the very first time I had to explain this to somebody. It was on Twitter, naturally, but way back in 2013 when Twitter really did properly qualify as an echo chamber. I thought we were all pretty much over racism, and that nobody in their right mind would flirt with authoritarianism just to own the libs, all of which is to say—2013 was a very long time ago. And midwives in Ontario were protesting wage discrimination and a gender gap, which meant they made significantly less money than (mostly male) doctors for bringing babies in the world. I tweeted about it, because I think the work that midwives do is sacred, and in late 2013 it had only been a handful of months since I’d recently had a baby. And it would turn out that support for midwifery is more controversial than you might expect, or at least than I would have expected in 2013, back when I was still mostly unaware that we live in a world absolutely steeped in misogyny. Someone accused me of being a midwife or paid by the midwifery lobby (Big Midwife?) to be tweeting in support of their side on the issue, and I was so confused by this. No, I was just a person with an opinion, who supposed that my perspective on an issue mattered. How cynical can you be not to imagine that such people actually exist?

I am not an activist. I’ve said this more than a couple of times over the years, but mostly because I don’t feel I have the proper cred for such a designation. I’ve never chained myself to a tree, or gone to jail, to stared down police in riot gear, and when faced with confrontation, my first impulse is to cry. Sometimes I sign online petitions, but I don’t think that really counts.

In 2016, Tabatha Southey published an excellent column in the Globe and Mail headlined “Might I demand that we stop agitating against activism?” It was in response to an ad campaign from the Ontario Medical Association about changes to health care in Ontario (which seems very quaint now, that they thought they had something to complain about then…) featuring a person who was supposed to be an “everywoman”—”I have never protested a day in my life,” she explains, as though somehow this makes her complaint more legitimate than a person who was campaigning for nuclear disarmament in the 1980s. Southey writes, “Since when did never having been so passionate about something that you felt the need to speak out about it become an express ticket to the moral high ground?”

I was thinking about all this the other weekend when I went to The Festival of Literary Diversity (the FOLD) in Brampton and attended the absolutely terrific “My Body is an Activist” panel with Imani Barbarin, Joshua M. Ferguson and Adam Pottle, moderated by Carrianne Leung. All three writers spoke about activism, identity, limits and labels. Pottle pointed out that what many people might call “activism” might actually just be people trying to live their best lives—and the way that “activism” as a label can serve to reduce that experience. He also noted how calling someone an activism (or something “activism”) also serves as a convenient way of getting rid a nuisance, how it’s something easy to push aside.

Which is where I began thinking about Southey’s article again, and the woman on Twitter way back in 2013. About the weaponization of the word “activist,” which is a way of rendering activism as meaningless, inconsequential (which, indirectly, was precisely what was happening in that 2016 OMA ad).

Which is why I have to say things like, “I am not an activist” quite often now in order to legitimize the ideas I am expressing, never mind that I literally have a collection of broomsticks and wooden dowels on my porch for securing to placards that read things like, “Fund Public Schools” or “Hands Off My Uterus, You Weird Religious Ding-Dong.” It’s been two years since I started carrying around a banner in my purse that says, “My Body, My Choice,” and I’ve had occasion to use it. I have become that weird mom in the school yard gathering signatures for her petition protesting cuts to school funding, and indeed have co-organized an Action Day for this Thursday, for which I am baking four sheet cakes and we will be distributing cards for our postcard campaign. But I am not an activist.

I am not an activist, because the only way for one’s ideas to be worthy of consideration is to stand for nothing and accept the status quo, which is just how the government in power likes it. (“The constant disparaging of activism – the casual acceptance of the idea that the more dedicated a person is to a subject, the less they are worth listening to on that subject – has been fashionable for a while now,” wrote Southey in early 2016. “The plethora of ‘Taxpayers for …’ and ‘Concerned Citizens Against …’ groups is a reaction to that trend. These people are ‘concerned,’ about an issue, you see, having apparently rejected ‘Peeved’ and ‘Indignant’ as descriptors. We are to understand that while, yes, these groups are campaigning to bring about political or societal change through vigorous action, the difference is they’re right.”)

There is the thinnest line for who is permitted to stand up for anything these days. I have found over the last five years speaking out about my experience with abortion and speaking up in favour of reproductive justice and increased access to abortion in Canada and abroad that having a uterus, children and lived experience of abortion doesn’t count for as much as you’d think in the minds of some people, and these matters really should be left in the hands of random guys on Twitter or 21-year-old virgins.

And while you’d thinking that speaking up for children’s right to well funded schools would be a less controversial topic, it’s proven not have been. On this topic too, there are men on Twitter who are quite sure I don’t have the right to hold opinions on this topic, that I’m a partisan shill. When I inform them that I’ve been speaking out about education funding models for two consecutive governments, they demand to know the exact date when I started, and why I wasn’t shouting about this a decade ago, because it’s not a new problem. So either I am not an activist, or I’ve not been activisting enough—and it’s almost as though forces are trying to make it impossible for people to express their ideas, to have dissent, for us to work together as communities to bring around any kind of change at all. (Unless we are concerned taxpayers, which apparently is fine.)

But of course, I am an activist—in spite of myself. In 2019, I don’t how anybody can’t be. Whether you’ve got wooden dowels on your porch, or you’re petitioning your friends and neighbours about climate change, or you want your children to have a future that isn’t hellfire, or you want the right to decide not to have children at all should you need to, or you care about endangered species, and affordable housing, and you want the police to cease stopping Black people when they’re walking down the street, or you understand now the way women are vilified when run for office and you want to do something about it, or you’re concerned that racists are so emboldened and flying Nazi flags is actually a thing, and you would really love some democratic reform in order for the stupidest people not to be elected into office over and over again.

We should all be activists. Short of that, we should all be aspiring to be activists. If I don’t see you while I’m collecting signatures on the playground, then I will see you in the streets.

May 13, 2019

Spring, by Ali Smith

I wasn’t so much addicted to the spectacle as to the ongoing certainty that the next click, the next link, would bring clarity. I felt like if I watched everything, if I read every last conspiracy theory and threaded tweet, the reward would be illumination. I would finally be able to understand not just what was happening but what it meant and what consequences it would have. But there was never a definitive conclusion. I’d taken up residence in a hothouse for paranoia, a factory manufacturing speculation and mistrust.

Olivia Laing, “I was hooked and my drug was Twitter”

I don’t always love Ali Smith’s work (How to be Both did not do it for me) but I cannot overstate what the books in her seasonal quartet have meant to me since the world descended into Worst Possible Timeline, which I date to June 16, 2016, the day that British MP Jo Cox was murdered outside her constituency office by a man who shouted, “Britain First.”

What is going on here, I remember asking myself in horror (except with more expletives) and then again a week later when the Brexit verdict was delivered, and six months after that when Hillary Clinton did not become the first woman President of the United States, and then basically about every ten minutes ever since then. Clinging to Twitter, as Olivia Laing describes in her essay, to make some kind of sense out of this real time nightmare—but then again if there was any sense to be made of it, Twitter would not deliver, because it’s in their interest to keep me refreshing my timeline, to have me yearning for clarity and illumination but never actually delivering.

But then in the Spring on 2017, Autumn arrived, the first book in Ali Smith quartet, set just six months before I was reading it, which is a remarkable turnaround in the world of publishing. And the books in this series are the closest I’ve ever come to the clarity and illumination that Laing is seeking in her essay, the clarity and illumination that I’ve been craving ever since I started to realize that the world is a vastly different place than I’d supposed it was. Even though it’s not so clear or altogether illuminating, but still—that Smith is fashioning art and story out of these times that we’re living in. I get comfort from that. A lazy kind of comfort, possibly, and her novel Winter—published in January 2018 (I walked through a blizzard to get it)—alludes to this. That turning these events into literature puts then at a distance that makes me feel better, and maybe I don’t deserve to. Look, here’s art. These things are cyclic. It will be fine.

It’s not fine, and I know it’s not fine, but I am still roused at Smith’s ability to articulate our situation in her novels. Spring came out this month and begins with four pages of run-on text that appears to be cribbed from Twitter. “We need the dark web algorithms social media. We need to say we’re doing it for free speech.” And then the story begins with a screenwriter who is mourning the death of an old friend who was briefly his lover and who was also his mentor. (What is going on here?) He’s on a train platform in the north of Scotland, and he’s mostly lost in nostalgia, and the train doesn’t come.

In the next section, more disturbing zeitgeist (“We want you to know how much your face means to us. We want your face and the faces of everyone you photograph and the faces of all your friends and the faces of the people they photograph recorded online for our fun data archive and research…”) and then a young woman called Brittany Hall who works as a guard in a detention facility for asylum seekers and/or illegal immigrants—but something strange is afoot. A young girl who managed to get through the barricades, past the guards, inside locked doors and into an office where she convinced the powers that be to have the facility professionally cleaned. Which is to say that it no longer smells like shit in this place where actual people live anymore, even though Brittany Hall has forgotten these are people, because you have to forget, or else how can you bear it. And Brittany Hall is going to end up with this girl on a train to the north of Scotland where they’re going to cross paths with the screenwriter, and like the other two books in the series, this is a novel about art, and the nature or art, and the purpose of art. About hope (springs eternal), because what is art but hope embodied after all.

May 13, 2019

Gleanings

- I wasn’t so much addicted to the spectacle as to the ongoing certainty that the next click, the next link, would bring clarity.

- She was not a brand. She was a warrior in a cardigan.

- But men themselves also need to think more carefully about how they behave in public spaces.

- But here’s what I notice more and more often… this focus on the ‘want’

- I marvel that we can swim up and down in harmony: overtaking, capitulating, motioning to pass with a silent frantic wave, smiling a nod of thanks between gasps and tumbles.

- When I wake in the morning, I am no longer waking to darkness.

- This is my neighbour’s plot. Rhubarb and raspberries so far. He will have tomatoes that should win a prize by August.

- I pulled my suit on the other morning at the pool, only to find the top band had entirely unattached from the rest of the suit.

- The oak table became Mum’s worktop and her most valuable tool…

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.