June 17, 2019

Gleanings

- Amelia Bedelia turns passive aggression into a kind of art.

- Sharing and generosity are at the core of our values and at the core of my art. Sharing, giving and generosity is a central tenet of my life. It’s tied to love, respect and compassion. It’s tied to justice.

- I expect the process of writing a novel might just involve a lot of thinking you are unworthy.

- The first day of outdoor swimming in Toronto is truly my favourite day of the year.

- ‘taxi!’, by helen potrebenko

- There’s some science behind the appeal of comfort reads, it turns out.

- And then I started thinking about community and about belonging.

- So after all the white and drabness of the other season, suddenly we arrive at summer.

Do you want to learn more about to write good things to read online? Check out Blog School and sign up for the newsletter.

June 14, 2019

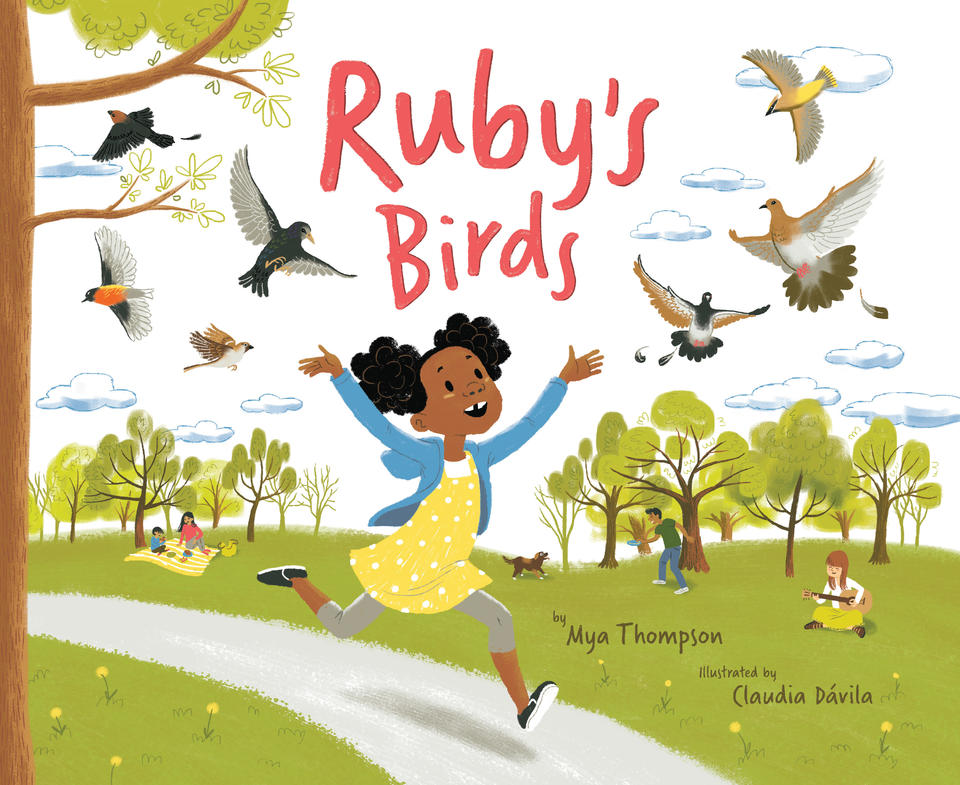

Ruby’s Birds, by Mya Thompson and Claudia Dávila

Having recently read and loved Ariel Gordon’s celebration of urban forests, not to mention still coming off a recent trip to New York City, Ruby’s Birds, by Mya Thompson and Canadian illustrator Claudia Dávila (we’re big fans of hers) is high up on our list at the moment. It’s the story of Ruby, a young girl with too much energy—so much so that she’s driving her family batty as they’re cooped up in their apartment. And so when a neighbour offers to take Ruby on an adventure to Central Park, she’s totally game, and brings her usual merrymaking self—which is a bit of a problem. Because they’ve gone birding, for which a person must necessarily be quiet, and be patient. Which does not come easy to Ruby at all, but then her patience is rewarded at the sight of a golden-winged warbler.

“We move carefully. We’re serious. We pay attention. We watch for tiny movements in the leaves. We try and try.”

Ruby’s Birds is published by Cornell Lab of Ornithology, whose mission is advancing the understanding and protection of the natural world. The story is fun, the illustrations interesting and dynamic, and the book concludes with information about city birds, the Cornell Lab’s Celebrate Urban Birds project, a list of 14 different species that can be located in the pages of the book and even in the reader’s own city, plus a list of inspiring tips for nature walks. It’s a great book to inspire readers to get outside and get exploring, and perfect for spring.

June 13, 2019

We Need Each Other: Part Two

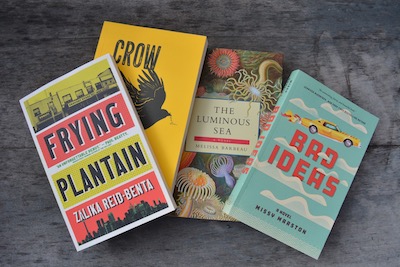

No writer is an island, as much as many of them try to fashion themselves as such. But those of us who are paying attention know how everything is connected. (Do read Kimmy Beach on how injections are friendship are essential to the writing life!). Which is why I think that having a bookstore with only four books in it is a thing that really matters.

Okay, hear me out.

Four books, each by writers who live in different parts of the country, published by four different Canadian independent publishers. But these books look good together, and side by side they’re selling a few more copies than they would have on their own. And as a Canadian writer, I benefit from this, even though my own book is not one of the four, not least because as a Canadian writer I am necessarily a Canadian reader, and so everything that promotes good books and reading is to my benefit. But also because getting these great books into the hands of great readers serves to enrich our reading culture, and a rich reading culture serves every single one of us with books to sell, even if it’s not my book they’re selling.

This is also why we’re encouraging readers to seek out Briny Books titles at their local indie bookstores, if they’re lucky enough to have one. Yes, indeed, we’ve got free shipping, but I personally know that a trip to the bookstore is even more exciting than a book in the post (even with the free shipping). Our mail order business is intended to woo the reader who is wedded to Amazon purchases or who has to drive for miles to land at a place that sells books at all, let alone excellent ones. But all readers and writers benefit from a culture in which indie bookstores are thriving, and so we want to help that happen. With bookselling too, as with reading, writing, and everything, it’s way more fun when you’re doing it together. It’s not a contest, or a race—it’s a network.

I want to challenge our notions of scarcity. Or maybe rather to acknowledge that even within a culture of scarcity, a spirit of of generosity is powerful, and that we will always have more when we have it together, because what we have in each other is actually priceless.

June 12, 2019

Echolocation and Meteorites

Echolocation, by Karen Hofmann

As a fan of Karen Hofmann’s novels (I loved After Alice, and What is Going to Happen Next is a title I’ve been recommending widely) I’ve been looking forward to her short story collection, Echolocation, which was published in April—and it did not disappoint. The stories themselves are wide-ranging in tone and style, as well as in their publication history, if Hofmann’s “Acknowledgements” are any indication—the title story was published in Chatelaine in 1998 (and now I am nostalgic for short fiction in women’s magazines, and women’s magazines in general. But I digress). Stories are written in the first person, third person, and even one in first person plural, which I liked a lot—about a group of colleagues retreating to a cottage after a conference, and it’s an incredibly orchestrated melee. “Echolocation” is a story of miscarriage and marriage. In “Virtue, Prudence, Courage,” two misfit newlyweds turn feral on their wilderness honeymoon. In “The Swift Flight of Data Into the Heart,” a woman’s long-buried secret is beginning to rise to the surface. As in What Is Going to Happen Next, this book is impressive for its broad scope and convincingness at all corners—suburban wives and mothers, middle-aged men, a family of immigrants from Bosnia, an ex-nun, an elderly painter who clings to her independence, and former trumpet player from a travelling band of people with dwarfism, although the narrator was taller than they would have liked, but they needed trumpet players, as all bands do.

Meteorites, by Julie Paul

I was also excited to read the latest by Julie Paul, whose last book was winner of the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize and made the Globe and Mail’s Top 100. Similar to Echolocation, Meteorites is a grab-bag of various delights, whose stories whose concerns include obnoxious step-children, ghosts, teenage friendship, brotherhood, a young daughter’s self-harming, an organist determined to persist after her arm is amputated, and also murder. The settings seem familiar, but something sinister lies at their edges—sometimes surreally so—which is part of what makes these stories such compelling reading.

June 11, 2019

We Need Each Other

This week in a blog post, Carrie Snyder made a note about her discomfort in receiving, and if her post had been a page in a book, I would have underlined the entire passage and made an annotation in the margin: YES!! But it’s strange for me, because I’m never expecting to feel this way. My instinct is to feel absolutely entitled to everything…until it arrives and then I want to sit under the table and hide. So that the two choices the end up available to me are between not getting what I want and being dissatisfied (and angry and resentful), or getting what I want and feeling tremendously uncomfortable. (“The one great thing about having your book rejected is that at least you don’t have to go through the agony of publishing a book,” is a thing that I’ve said lately.)

Launching Briny Books last week was a million times less stressful than launching a book—and I have so enjoyed learning more about marketing and the opportunity to market something that is less connected to me personally. (I am ridiculously sensitive, although I am working on it always, but the most 2019 emo thing about me is that every time someone unsubscribes from my newsletter, my feelings are hurt.) It’s been fun and exciting and I’ve been so pleased that others seems to find the idea (which is a pretty simple one) as compelling as I do. Getting comments on Facebook (and sales too!) from people who I don’t know and/or who are unconnected with my mom seems significant. My mom commands a vast and powerful social network, to which I have to thank for a sold-out book launch awhile back, but moving beyond the plane of her influence seems next-level to me.

But moving beyond would not be possible if not for my mom, and my friends, whose support of the project was overwhelming and amazing, even if it did make me want to hide under the table. The support of my husband too, who has devoted more labour than anyone else to the project, with web design and photography. To me, this entire experience has underlined the power and possibilities of collaboration and community. I am so grateful to everyone I know and love who purchased books and helped spread the work in their own networks. I continue to be overwhelmed by the kindness and generosity of people I’ve never met except on Instagram or through my blog, people in whose lives and experiences I’ve found myself become so invested, and who are incredible champions of the stuff I get up to. To my friends, who never show it if they’re tired of showing up for me, and all week I kept thinking, “What did I ever do to deserve all this goodness?” That there are people out there like you.

My favourite thing about Briny Books is that partnership is at the heart of it, though that’s primarily because it’s always my objective to make things as simple as possible. Sure, it’s great to support to independent bookstores in principle, but in practice too, there’s a lot going for the idea. They know how to sell books for one, as in bring in copies from the distributor and then ring the order through the till. Possibly my greatest strength as an entrepreneur is an openness to outsourcing—which comes of my greatest weakness as an entrepreneur, which is having no money. But what a thing, to put our strengths and passions together. I know that having Blue Heron as a partner in Briny Books has done good things for our reputation—and I know too that Blue Heron’s willingness to pursue a project like Briny Books is how they got their reputation in the first place, for ever pursuing fresh and creative ways to connect books with readers. And bringing books to readers is a kind of partnership too. In a community of readers, books connect us all.

Maybe what I’m trying to get at here is how surprised I am at the revelation that my reliance upon other people is actually a kind of strength, instead of its opposite.

(Even though once upon a time, I thought this reliance was something I must necessarily defy, possibly because I spent my formative years reading too many books by men, and that was when I was 23 and ran away to Europe with a backpack in order to discover myself—but the only thing I would discover was abject loneliness and a propensity for crying in phone booths.)

But perhaps reframing receiving in these terms—of strength and community—is what’s necessary to help me work through the discomfort of receiving. What if it’s receiving care and support from others that makes us our truest selves? As Briellen Hopper writes in her essay, “Lean On,” “I experience myself as someone formed and sustained by others’ love and patience, by student loans and stipends, by the kindness of strangers.”

My friend Ann Douglas has been writing a lot about community lately and inspiring so much of my own thinking, and I appreciate what she said in this piece about thinking of community as a resource instead of a burden. “The more you turn to other people for support, the more you give them the opportunity to support you, which feels really good to the other person,” she explains. Which is true: I remember one day a few months back, Ann reached out to me for something, and I felt so buoyed by being called upon, by having something to offer.

Similarly, I have a very generous and kind neighbour who is forever bringing us gifts and doing us favours, and the best email I ever received from him was the day he needed to use my printer. When you get to help out your neighbour, you’re also contributing to making a world in which people help their neighbours happen. Bad news though: he did use our printer, but has since approached me with a problem that he’s having, which is that he has too much beer, but wasn’t sure if we liked beer, so he’d felt uncomfortable bringing bottles over.

I am beginning to accept that I will never outdo this person when it comes to kindness and generosity…

But maybe it was never a contest anyway?

June 10, 2019

Gleanings

- Jennifer Weiner created the perfect reading nook. No one used it.

- Whatever we do next, as adults of our species, will determine everything.

- Women, can two or more of us get together without mentioning our bodies and diets? It would be a small act of resistance and a kindness to ourselves.

- What does it mean to be “the village” — to not just long for connection with other people but to actually show up and build those kinds of relationships and, along the way, create community for yourself and other people?

- What a gift is this life, the tawdry glamour, the writing, the body that I’ve been given and that has taken me this far.

- As the years tick past those early days, parenting life becomes less visible, doesn’t it? I suppose you are meant to know what you are doing by then?! Imagine that! Because we’re just winging it like way back when.

- So yes, we’re uncomfortable with the notion that genocide can happen within our borders, in our communities, on the long highways of our country, in its rivers where so many young women were thrown…

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

June 5, 2019

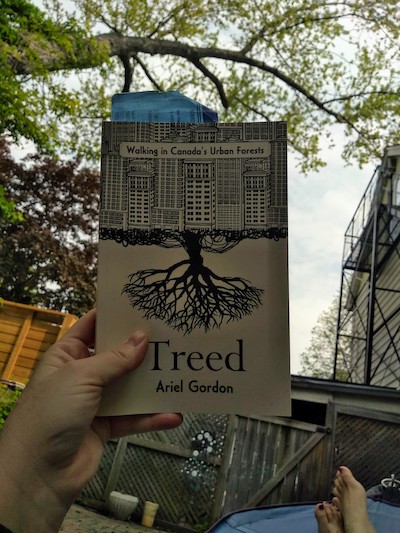

Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests, by Ariel Gordon

Ariel Gordon’s brand new essay collection Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forest, was just the book I needed last weekend, a weekend we headed into amidst news headlines of rising water and forest fires, which I was finding positively dispiriting. And yes, of course, it is supposed to be dispiriting, but I also just can’t live like that, so certain in my despair. I need to still love the world, and find wonder here, and it’s a kind of compulsion, which is what Treed is all about as it makes a kind of sense of the messiness—of hybrid spaces, our history of colonialism, of contradictions, tension and balance, and the absolute insistence of wild things. The very fact of an urban forest.

“But this is a multi-use space. It is a public space. Which means people bring to the forest what they have: Dogs. Children. Inappropriate nudity.”

Treed is also a book about mushrooms, which if you’ve known Gordon online for any length of time is unsurprising, and about the way that mushrooms became her gateway to Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Forest as she began to explore this space which was overwhelming in its immensity, but noticing mushrooms was about detail. And the book’s third essay is a diary of these explorations as Gordon moves through the seasons of the year and of her life, and it acquaints us with the subject, our intrepid narrator, and the space and trees that come to fascinate her.

There are challenges and complexities: balancing urban trees with development, fighting diseases and pests, that trees have a natural lifespan at all, invasive species, monocultures, balancing the needs of people with the trees they live amongst, and Pokemon Go vs. proper exploring (and her cat), and Gordon shows that these complexities are more complicated than she properly understands, a perfect balance impossible, the tension inherent. The challenge of being a living thing on the planet.

I loved this book, which was also about balancing motherhood and writing, the family and the self, solitude and community, city life and the inexorable fact of nature, abject despair indeed and the wonder that is everywhere, if you care to look—starting with the mushrooms.

June 4, 2019

Briny Books is here!

Yesterday was the launch of Briny Books, a project I’ve been scheming over the last six months, with the help of my web-designer/photographer husband, and the amazing Blue Heron Books who came on board when I sent an email with the subject heading, “So, I have this dream…” The dream, which is probably your dream too if you love books as much as I do, is to own a bookstore—but I have no business acumen, or capital, or experience in bookselling, which is a proper vocation for sure. So how to scale that dream down to something achievable, something meaningful that could still make a difference? And Briny Books is the answer, a boutique online bookstore—whose purchase links direct to Blue Heron’s site so they can take care of that end of things, which is in their wheelhouse—and they’ve even finagled free delivery. But curating an incredible book selection? Why, of course, that IS my wheelhouse, and oh my goodness, is our inaugural lineup ever exceptional. I’m so thrilled by all four books and so proud to recommend them, because I know that readers will respond and appreciate what these amazing authors are up to, authors and books that should be on everybody’s radar. And while I understand that through Briny Books, we don’t (yet!) have access to everybody, we do have the opportunity to bring these books attention they mightn’t have received without the project, and likewise to bring to readers these amazing books that they deserve to be falling in love with. The books will also be featured in-store at Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge, and we hope that other booksellers will stock and even display our picks, and this way everybody wins, a richer reading culture, little-by-little, step-by-step.

I’m grateful to everyone who’s as excited as I am.

June 3, 2019

Gleanings

Whew! A bumper crop of good things to read online this week (or “on the line” as my youngest daughter said to me today when she was trying to explain something she’d seen on the internet). Gleanings was on hiatus last week while I was on vacation, which means I’ve got even more than usual to share this time. Thank you, as always, for reading!

- First, I stumbled upon a Chuck E. Cheese training video from the 1980s when I was procrastinating on my master’s thesis.

- I was already in love with notebooks and spying before I met Harriet, but she made that okay.

- How Claudia Kishi Inspired A Generation Of Asian American Writers

- What are children to do when they realize that the adults in their lives are making it up as they go along.

- This year I even considered scaling back the unicorn party as a sort of white flag gesture.

- What my mother likely hadn’t considered until that moment was that my books, and my Anne books in particular, were the constants in my life.

- You want to be building community, so that when you need to access community, community’s there for you.

- This is what it looks like to have a feminist husband.

- What I’ve learned from being vulnerable is we are not alone, we are all different, and we all desire to be accepted and accept ourselves fully in this journey we call life.

- it’s the swim cap, it gives me a facelift

- What are your indelible words?

- My goal is to make this summer all about having fun in the water.

- Holy cow. Can you even believe an amazing baker is whipping up ’embroidered’ cakes?

- nanaimo ice cream bars (!!!)

- I have learned the hard way that this is a lesson that everyone comes to in their own time–if a friend is fretting endlessly about what to wear to a party, “What makes you think everyone is going to be looking at you?” is not an immensely helpful thing to say.

- Over the years we’ve lived here, I’ve grown to love the homing pigeons that live a few doors down.

- I’d be a faster reader if I read one at a time, I imagine.

- It’s a bit of a shame that the in-between has not really had its time to shine, isn’t it?

- I’m especially glad that I can keep the old and useless and rejected in use a bit longer.

- If any of the eyeballs in your manuscript make sparks or are steely or artless, I would further invite you to try to make that happen and ask someone to tell you exactly what you’re doing with your eyes.

- Women acting collectively in open and angry defiance can change history…

May 30, 2019

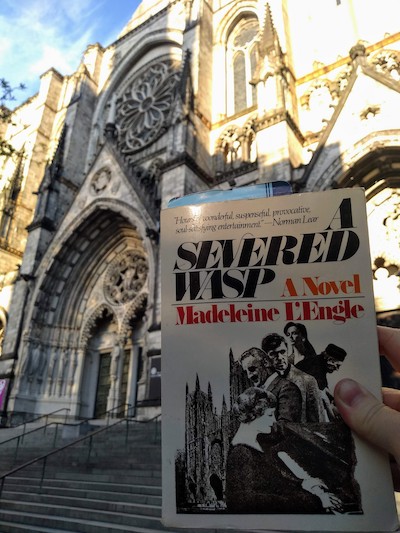

The Severed Wasp, and New York City

Sometimes, one’s inflexibilities rub up against each other in complicated ways, for example: yes, one wants to read Madeleine L’Engle’s lesser known novels in chronological order (ie two more Polly O’Keefe books to go before I read The Small Rain/A Severed Wasp) but also: I really want to read A Severed Wasp during the weekend we’re in New York, because of its setting (which is the same setting for The Young Unicorns, a novel I adored). So what to do? Well. because I am all cool and laidback, I just skipped ahead to be the other books, NBD. Ha ha.

So first to The Small Rain, which was Madeleine L’Engle’s first novel, published in 1945, 37 years and 29 books before its sequel, almost 20 years before L’Engle made her great success with A Wrinkle in Time. And…it was not good. There were interesting tastes of what would come to be L’Engle’s literary preoccupations—it begins with a young girl being cared for by a friend of the family, because her musician parents are unable to be there for her, which reminded me of Maggy in Meet the Austins. There is romance, there is melodrama, there are weird dynamics between teenage girls and grown men, there is a sea voyage. There are weird problems with plot and pacing, and I didn’t really like the book–it read like something terribly old fashioned written by someone who was terribly young and trying to be terribly edgy, and the effect was kind of terrible. I am glad I read it, but I desperately hoped that A Severed Wasp would be very different, but then I supposed it would be, written 37 years and 29 books later. Possibly, L’Engle has learned something about writing novels in the meantime.

A Severed Wasp—published in 1982, and blurbed by no less than Norman Lear!—finds Katherine Forrester in her seventies now, instead of a teenage ingenue. Now widowed and retired after a hugely successful career as a pianist, she has returned to the scene of the previous novel, to New York where she came of age and suffered her first heartbreaks, and she runs into her old friend from Greenwich Village, Felix, who was once a violin-playing beatnik, but now he’s a bishop, which is the way things go in Madeleine L’Engle novels, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on New York’s Upper West Side.

Which is a cathedral I first encountered through L’Engle’s The Young Unicorns (1968), the one book in the Austin series that did not feature Vicky at its centre and which was odd, plot-driven, and very compelling. Dave Davidson, who was a teenage boy in the first book, appears again in this one, now grown and Dean of the cathedral, and married to ACTUAL Suzy Austin, who has realized her dream of becoming a doctor, and is also now a mother of four. Interesting because Suzy had been the one who’d always challenged her own mother’s anti-feminism, and I’d wondered about L’Engle’s emphasis on women who had abandoned dreams of career for families, as though the two were impossible to balance. But here was Suzy, doing it all, which Katherine thinks about a lot, because she is conscious of having failed her own children as she’d travelled and toured for much of her daughter’s childhood, and her daughter now remained quite distant from her—in terms of geography and emotion.

But then we will learn that Katherine’s relationship with her daughter is complicated not just for this reason, but also because the daughter was conceived not with Katherine’s husband who’d been castrated at Auschwitz, but by her Nazi prison guard, with whom she’d had a brief affair right after the war. I know, right? The Katherine of The Small Rain has not lost her taste for melodrama, but the stakes have been raised much higher, plus Katherine is receiving obscene phone calls, Felix is also receiving threats to reveal his homosexual affairs, her pregnant downstairs neighbour’s husband has having an affair with a man, the Bishop’s wife is a former pop-singer whose past involvement with drugs continues to haunt her, the streets of New York are dangerous and riddled with crime, and Suzy Austin’s youngest daughter had lost her leg not long ago after being hit by a car in what may or may not have been an accident.

Too much, all of it. Also, too many racist stereotypes—the worst. But the plot did unfold in a most compelling way, and actually being in New York as I was reading made the whole thing much more meaningful to me. (I don’t think many people make A Severed Wasp pilgrimages. There wasn’t even a copy of the book in the Toronto Library system. I had to order a secondhand copy. My instagram hashtag was the only one!) We went to the Cathedral on Friday evening (“The very size of the Cathedral was a surprise…” the book begins. It was!) and got there too late to be able to visit or even explore the grounds, but I just wanted to see it anyway. (Would have been interested to see the plaque that is apparently there once the Cathedral was made a literary landmark because of L’Engle in 2012—she was a writer in residence and librarian there for decades.) We did get to the see the albino peacock in the garden, although the peacocks in the novel seemed to have been conventionally coloured.

We had dinner across the road from the cathedral, and then it was very exciting to be reading the next day and realize that the very place we’d eaten at—the V&T—was described by Suzy Austin was “the best pizza in New York.” It really was! And then the next day we visited other parts of the city, and though I never got to Tenth Street, where Katherine lives in Greenwich Village, we were just close enough that I felt her presence and the streets she’s describing. And the book was in my bag the entire weekend, to be taken out and read on long subway journeys—not that Katherine ever took the subway. I don’t think she even knows it exists.

“Odd, how complex and intertwined life is. Every time I think I’m settling for chance and randomness, then pattern enmeshes me in its strands.”