January 27, 2017

Picture Book Wisdom

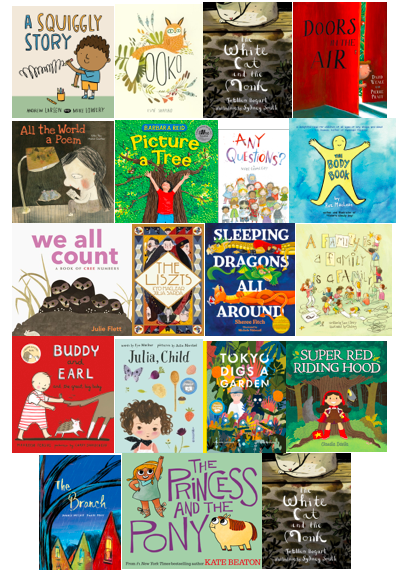

It’s Family Literacy Day today, and I’ve written a post at 49thShelf about how everything I know about the world I’ve learned from picture books. Including, “Dance in the kitchen. Don’t do the dishes” and “Far more than any fame, enjoy the peaceful pursuit of knowledge. Treasure the wealth to be found in your books.”

You can read all the words of wisdom here, and make sure you pick up these great titles if you haven’t already.

January 26, 2017

Rebecca Solnit, and on “joy as an initial act of insurrection”

The 2003 anti-war protests turned out to be pretty foundational for me, but in all the wrong ways. I was living in England then, which was not my country, and my actual country wasn’t going to be invading Iraq, so it was easy to think the whole thing had nothing do with me. Of course, I knew that invading Iraq was going to be a terrible idea, and I still don’t understand how anyone could have though it wasn’t a terrible idea (or how anybody who thought was a good idea got to be recognized as an authority on anything after that). But still, apart from arguing with people online about how no one really likes being “liberated” via bombs being dropped on their houses and their children being killed, I was not particularly moved by the situation. In fact, I was distinctly unmoved. A colleague of mine was rushing about the office on her way to go and join the protest in our town, and I remember her glee; “I love politics,” she said, and I thought everything was wrong with that. That politics should be a necessary means to an end, which is ordinary life, and not a reason for being.

Will you forgive me? I was 23. And while I still find mobs of people congregating and shouting together unnerving, no matter what they are saying (because when The People start speaking with one voice, then something has certainly gone amiss, I mean, have you ever met people?) I realize how wrong I was about the necessity of activism. And that activism always fails when it’s regarded as a means to an end, when you go home too soon, rather than a process.

“Paradise is imagined as a static place, as a place before or after history, after strife and eventfulness and change: the premise is that once history has arrived change is no longer necessary. The idea of perfection is also why people believe in saving, in going home, and in activism as crisis response rather than every day practice.” —Rebecca Solnit

On Saturday, when our family joined the millions of people all over the world marching for women’s rights, I too began to see the point of the glee. That the glee wasn’t simply fervour, but that it was also a kind of relief, and it was more substantial too than merely glee—it was joy.

“Joy doesn’t betray but sustains activism. And when you face a politics that aspires to make you fearful, alienated, and isolated, joy is a fine initial act of insurrection.” —Rebecca Solnit

Of course, initial act, is a very important distinction.

It was a terrific event, and I refuse to apologize for it having flaws the same way I felt I had to apologize for admiring Hillary Clinton. Nope, in the name of FEMINIST FEMINIST FEMINIST FEMINIST, and Nellie McClung. Read Jia Tolentino in The New Yorker: “But this is precisely why the Women’s March feels vital. Of course it’s difficult to pull together an enormous group of women who may have nothing in common other than the conviction that a country led by Trump endangers their own freedoms and the freedoms of those they love. That conviction is nonetheless the beginning of the resistance that those planning to attend the march hope to constitute.” (And no, not inviting Pro-Life women is not “intolerance,” because if you’re actively campaigning to restrict my reproductive freedoms, you go find another yard to play in. That is not and can never be feminism, no matter who you are.)

It’s necessarily awkward, it just is, to be, for example, a white woman dipping her toe into notions of social justice, as women of colour have been swimming in these seas for ages. It’s sort of embarrassing and uncomfortable to admit that the is new to me, that I was wrong in 2003 and in all the years after when I continued to think that “ordinary life” and politics was something a person could draw a line between. It’s showing up at the party and not knowing the dance, and looking really stupid, but we’re coming anyway—and we’re going to be fucking stomping our lady-sized feet with all the rest of them. The best of them.

“Resistance is first of all a matter of principle and a way to live, to make yourself one small republic of unconquered spirit.” —Rebecca Solnit

January 24, 2017

Feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist is for me.

During the past year or so, the delusion I’ve been most sorry to let go of is the one in which most people, as I do, simply see feminism as a synonym for “normal.” It’s why it never bothered me much when some people felt uncomfortable with the term, because it didn’t really matter what you called yourself. If you were a person who felt that women were deserving of voices, votes, careers, multifaceted lives and ownership of their own bodies, then you were a feminist, or so I thought. And who didn’t think that? But it turns out..a lot of people do?

From the appalling US election and its stunning results, it has been affirmed to me that misognyny is actually a thing and that for millions of people, women’s lives matter less than “teaching an unlovable female scholar a lesson she won’t forget.” When I question the validity of the Men’s Rights Movement on twitter, ugly beardos jump into my mentions for weeks afterwards calling me a cunt. When I continue to speak up about the importance of access to abortion, while the responses are predictably yawnish (“if you don’t want to get pregnant, don’t have sex, you slutty murderer”) the hatred toward women in general and people’s consternation at concept of our own agency over our bodies and our lives is palpable. Women’s torture and pain gets picked up and used as a tool by people who hate women and Muslims, and wonder why we’re taking to the streets when FGM is a thing in the world (never mind that these people have never stood up for women a day in their lives, except when doing so permits them to be unabashedly racist) or how I can stand up for reproductive rights while women in India are aborting female fetuses. The response to all this being: Because women’s lives are terrifyingly, fervently and violently devalued everywhere, you fucking asshole, and you are part of the problem.

So what to do? My favourite solution was found in a Facebook thread in which a friend of mine was discussing the violent pushback she’d received from engaging Men’s Rights Activists online. She was dismayed at the backlash, but a friend of hers had a suggestion, a piece to the vast puzzle of disentangling our current misogynistic anti-feminist mess. She wrote, “I am using the word feminism in every project I do now, my bio and website. It is all feminism. All the time.”

And I love that idea. All day yesterday, a song was running through my head, “Feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, is for me,” to the tune of John F. Kennedy’s 1960 campaign theme song. I’ve put “feminist” in my twitter bio, and made my “My Body My Choice” sign part of my header photo. My book comes out in six weeks, and it’s feminist as fuck. I’m learning how to be a better feminist. I’d get the women’s symbol tattooed to my ankle, but I won’t, because I already did that 14 years ago, but still. If we’ve ever needed a moment to be post-post-feminist, that moment is now, and I don’t fucking care if you don’t like it.

January 20, 2017

Have You Seen My Trumpet?, by Michael Escoffier and Kris Di Giacomo

Tonight at dinner, Harriet told us a story. “Today for Show and Tell,” she said, “Eric brought in a diaper.” A diaper? “Yes,” she continued. “He punched it, and then he cut it in half and took these things out from inside it, and he put it in his jello bowl, only there wasn’t any jello in it.” I was trying to make sense of this. “So it was like an experiment?” I suggested. The insides of diapers are filled with these gross little gel balls that I only know about because of the times(s) I put a diaper through a wash cycle and it exploded (don’t ask).

“And then he ate it,” said Harriet, and I said, “What?” and we all started laughing, quite hysterically, the way you might if you were eating dinner, someone ate a diaper, and the world’s worst man was being elected the American president tomorrow.

At certain moments, absurdity is fitting, and not much else these days is making the me laugh the way I like to laugh, which is to say, so hard that I shake noiselessly with one of my eyes closed—trust me when I tell you it’s very attractive. At certain moments all you want is a picture book with a sea urchin, a gruff fly, a missing trumpet, and a bat that’s sitting on the toilet. In 2016, the word of the year was “surreal,” and so all this is quite in keeping with the zeitgeist.

Have You Seen My Trumpet?, by Michael Escoffier and Kris DiGiacomo, is a book that’s brought delight to all of us during the past few months. Ostensibly the story of a small girl searching for a trumpet (that doesn’t turn out to be quite what you’d expect), the book’s true charm is spread after spread of bizarre beach scenes with appealing illustration and engaging, amusing details. On every page, a question is asked whose answer is to be found in not only the illustration, but also the question itself—and don’t you love that smug fish (above), who’s hogging all the pails and is sporting his I Love Me t-shirt?

The strangeness of the English language is underlined by this exercise—because indeed, the crow thinks it’s too CROWded, but that’s not we say it. And while it’s true that the owl has fallen in the bOWL, we don’t pronounce “bowl” as “bowel.” Which brings us to everybody’s favourite page, who’s in the BAThroom indeed?

It’s almost as weird as a kid who brought a diaper to Show and Tell and ate it, and makes as much sense as anything.

January 19, 2017

I don’t want to tell them, “Nothing.”

“One day my daughters will ask what I did to save the world for them, and I don’t want to tell them, ‘Nothing.’” I wrote a piece for Today’s Parent about why I’m taking my daughters to the Women’s March here in Toronto on Saturday.

See you there, or in solidarity?

January 19, 2017

The 1980s: Macleans Chronicles the Decade

Three years ago, I wrote about the importance of using books as literal building blocks, but it’s true that our metaphoric bookish building blocks are always what’s most fundamental. I suspect that somewhere deeply twined into my DNA is the book The 1980s: Macleans Chronicles the Decade, published in 1989 by Key Porter Books. It is possible that no one, apart from the book’s editors, have read this book as avidly as I did, for years and years, and at point in my life too when my brain was still forming so that its images are now seared upon my consciousness—in particularly, unfortunately, a photo of Lech Walesa fishing in his tiny underpants. It would be years before I learned why Lech Walesa mattered, and even once I did, I’ve never been able to disassociate him from his weird blue plaid briefs.

1991, of course, was the end of history, according to Francis Fukuyama, and this is the lens through which I viewed this book, perused its pictures, fascinated. History was done. In my recollection, I was literally in my grade seven history class when the Soviet Union was dissolved—though I am not sure how this is possible because the coup was in August and the union was finished on Christmas, and at neither of these moments was I at school, but still. It’s the idea of a thing. Suddenly all of history was there in the past, and I remember wondering what The 1990s: Macleans Chronicles THAT Decade would look like. But my family never got that book. If history is finished, who needs a chronicle after all?

A copy of this book lives on my shelf, and I don’t leaf through with the same regularity I did as a child, but I did the other week, after two months of feeling so downtrodden, uncannily not at home within the world in which I find myself. I’d read somewhere about the psychology of nostalgia, and how for all of us the moment of greatness in the past lies precisely when we were on the cusp of everything, with so much hope. Remember the ’80s, I was thinking, a decade so ripe with possibility, Lech Walesa’s underpants aside. But then as I started flipping the pages, seeing those iconic, devastating images—the Challenger explosion, famine stricken children in Ethiopia, Bloody Sunday in Beijing, the body of a child buried in ash after the gas leak at a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India; another dead child, lying with its mother, the casualty of poison gas attacks in the Iran-Iraq War; terrorist hijackings, albeit the retro kind when in the end the bad guys let the hostages go. But still. There’s an entire chapter entitled “Assassinations.” The ’80s were really terrible.

I want to hug the woman in the above photo who is protesting for the Equal Right Amendment to the US Constitution. “My foremother,” I want to say to her, “you don’t even fucking know.” Except she probably does, hence the look on her face. To think that 30 years after Henry Morgentaler, on the facing page, won his legal battle to strike down Canada’s abortion law, access to abortion would still seem so precarious (and only theoretical to Canadian women who live in so many places). #FuckThatShit has been my go-to hashtag these last few months as I grapple with “the absurdities that have been foisted on me and my neighbours,” to paraphrase Jane Jacobs. As Macleans chronicles the decade, things right now seem not much different from what they ever were.

None of this is a new story, in what I mean. Donald Trump and his ilk have always skulked the earth, knuckles dragging on the ground. Which is incredibly annoying and demoralizing, but also kind of reassuring too, that people have stood up against dark forces before and we can take courage from them. That goodness prevails, that things can get better.

None of this is a new story, in what I mean. Donald Trump and his ilk have always skulked the earth, knuckles dragging on the ground. Which is incredibly annoying and demoralizing, but also kind of reassuring too, that people have stood up against dark forces before and we can take courage from them. That goodness prevails, that things can get better.

The fight is never won, but maybe the winning is not the point, and instead the fight is.

January 17, 2017

Reconciling

The first definition of “reconcile” in the Merriam Webster is ” to restore to friendship or harmony <reconciled the factions>” but it’s the second definition that is more meaningful to me: “to make consistent or congruous <reconcile an ideal with reality>.” This definition certainly resonating in general, because in the past two months my ideals and reality have certainly been at odds, and reconciling that has been a process. The world is more complicated than I ever knew, which makes “restoring to friendship and harmony” seem like a pipe-dream, except: restoring, how? Because when was there ever friendship and harmony? It all sounds a bit like the notion of making America great again—elusive and facile. The first definition is a misnomer. Reconciliation is a process, and in order to be properly it is a process that will never end.

I’ve been thinking a lot about reconciliation lately, as I’ve been reading I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up. A friend of mine has also recommended Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair. I’m interested in and troubled by the way that people seem unable to constructively disagree with each other. (Another book along these lines that I’ve appreciated is Creative Condition: Replacing Critical Thinking With Creativity, by Patrick Finn.) I take some solace in the fact that people in disagreement, while inconvenient, is actually much healthier than the alternative, and that the potential for learning is infinite. A community in which everybody though the very same thing, and nobody challenged anyone or asked any questions, would be the very worst thing I could imagine. Worse even than the state we’re in now.

Remember my mantra for 2017, “Listen. Be Better.” I’m trying. It’s a challenge, and such an opportunity. Once upon a time, when I was young and things were simpler, I fervently underlined the following bit from Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, a play I loved: “This is the best time possible to be alive. When everything you know is wrong.” Such a prospect is more terrifying than I ever thought it would be, now that we’re kind of here and, you know, with the collapse of the world order, but still, there is something extraordinary about it too. I’m thinking about reconciliations big and small, in terms of domestic politics and literary criticism, even. Literary criticism, especially, because I wonder if this is a constructive metaphor with which to understand the process that has to happen in order for anything to happen.

Literary criticism, the best kind, is a conversation. A back-and-forth, a broadening, the prying of a text wide open. The best kind of literary criticism isn’t just about the text itself, but it’s about everything, and it invites big questions and many different answers. It provokes debate and causes the reader to change her mind—about the text, about the world. It’s not about whether a text is necessarily good or bad, but about the things it makes us think about, the places it takes its readers beyond itself. Literary criticism is a process, a collaborative ongoing pursuit which requires generosity, openness, consideration and respect on the part of the players involved. If no one’s listening, nothing happens, but if everyone is willing, anything can.

I was thinking about all this as I read Debbie Reese’s review of the award-winning picture book, Missing Nimama, which I reviewed in 2015—and you can read my review here. I am a huge admirer of Debbie Reese’s scholarship and advocacy about representations of Indigenous people in children’s books—she’s taught me a lot and she challenges my understanding in uncomfortable and constructive ways. She’s not afraid to go up against really popular authors—see her review of Raina Telgemeier’s Ghosts. I don’t always agree with her assessments of certain books, mostly because there are so many lenses through which readers approach a book, and hers is one, but I’ve never found her to be wrong.

While I still appreciate Missing Nimama and celebrate its success, Reese’s review shows me my own weaknesses in approaching it as a writer and a critic. Reese writes: “To me, however, Missing Nimama …. strike[s] me as something Canadians can wrap their arms around, to feel like they’re facing and acknowledging history, to feel like they’re reconciling with that history.” She continues, ” To many, this review…will feel harsh. Most people are likely to disagree with me. That’s par for the course, but I hope that other writers and editors and reviewers and readers and sponsors of writing contests will pause as they think about projects that involve ongoing violence upon Native women.”

And this is just the point. The pause, the reflection. Disagreeing is even okay, but it’s failing to consider that is inexcusable. The point is the conversation, the questions that are asked, which are far more important than the answers. And how we take these questions with us, this broadened perspective, with the books we read and the books we write. The point is to listen, and then be better.

UPDATE From Carleigh Baker’s review of Katherena Vermette’s The Break:“A generous storyteller, Vermette does not take it for granted that all readers will inherently understand how damaged the relationship between indigenous people and Canadian society has become. As readers, we can honour this generosity by not allowing ourselves to be lulled into a satisfying sense of camaraderie, having suffered alongside fictional characters. We can honour it by not repeating over and over how strong the women in this book are. It is true, they are strong. But let us not nod our heads in grim recognition of this strength, as if acknowledgement equals solidarity [emphasis mine]. Let us not pull our lips into thin lines and furrow our brows and express amazement at their resilience, as if its origin is a mystery. This makes it too easy to dismiss.”

January 16, 2017

Take Us To Your Chief, by Drew Hayden Taylor

I absolutely loved Take Us To Your Chief, by Drew Hayden Taylor, which was just as fun as its cover promised, and meaningful in a way I should have expected. Because while there is indeed something incongruous about First Nations’ science fiction, it’s only because I’ve never read any, not because it doesn’t make total sense. Is there a cultural group more familiar with notions of alien contact and invasion, for example, as in “A Culturally Inappropriate Armageddon,” in which broadcasters at a community radio station inadvertently summon attention from extraterrestrial beings? In “I Am…Am I,” scientists manage to create artificial intelligence, and the being (who is fed encyclopedias of knowledge) is drawn to notions of First Nations culture for its notions that all things, in fact, have souls, because the alternative is too hard to bear. In “Lost in Space,” an astronaut contemplates being Native in orbit: “What happens when you aren’t able to run your fingers through the sand along the river? Or walk barefoot in the grass? Or feel the summer breeze blowing through your hair?”

I absolutely loved Take Us To Your Chief, by Drew Hayden Taylor, which was just as fun as its cover promised, and meaningful in a way I should have expected. Because while there is indeed something incongruous about First Nations’ science fiction, it’s only because I’ve never read any, not because it doesn’t make total sense. Is there a cultural group more familiar with notions of alien contact and invasion, for example, as in “A Culturally Inappropriate Armageddon,” in which broadcasters at a community radio station inadvertently summon attention from extraterrestrial beings? In “I Am…Am I,” scientists manage to create artificial intelligence, and the being (who is fed encyclopedias of knowledge) is drawn to notions of First Nations culture for its notions that all things, in fact, have souls, because the alternative is too hard to bear. In “Lost in Space,” an astronaut contemplates being Native in orbit: “What happens when you aren’t able to run your fingers through the sand along the river? Or walk barefoot in the grass? Or feel the summer breeze blowing through your hair?”

In “Dreams of Doom,” an Ojibway journalist learns that dream catchers are a government conspiracy, actually devices to spy on and control First Nations people and keep them in line: “You will notice that since Oka and Ipperwash, other than a few flare-ups here and there, things have been relatively quiet.” In “Mr Gizmo,” a suicidal teenage point is given a wake-up call by a toy robot, in keeping with his culture’s understanding that all things are imbued with a soul (including, awkwardly, your toilet). The narrator of “Petropaths” is a man whose troubled grandson learns to travel through time via ancient codes in petroglyphs. In “Superdisappointed,” the shockingly common conditions of housings on a First Nations reserve (houses with mould, substandard drinking water) causes a chemical effect that renders one man an actual superhero. And finally, in the title story, three reticent Objbway men are taken as ambassadors from Earth when aliens arrive on the planet.

I’ve cited nearly every story in the collection here because they were all of them hits, no misses. I read this book exclaiming at how fun it was, and appreciating the way in which Taylor plays with sci-fi tropes, and that each story pursues such a different line. And yet this collection is not merely an exercise in whimsy either—Taylor’s stories are fervent arguments as to the continuing tragedy of colonialism, which seems to be a solid through-line from the past and right into the future. Familiar ideas then, to those who’ve been paying attention, but the point is that too few are paying attention and maybe more might be with this fresh and utterly engaging context.

January 15, 2017

Cake Breaker

I specialize in accidental cakes—I wrote about one of these in my favourite blog post ever. And here is another, in a post that was originally an Instagram post, but I was a few hundred words in before I realized it was a blog post after all. And so here it goes.

Yesterday there was no cake scheduled and there would have been no cake, except that when I was looking in a drawer for chopsticks at lunchtime (we were having udon noodles), I found an implement (shown in the photo above) which I’ve never used and cannot remember where it came from—from my mom or my aunt? Was it my grandmother’s? But regardless of origin, I didn’t even know its purpose: a comb? A plow for mashed potatoes? But then Stuart remembered that it was a cake server. “That’s right. But how??”

And then I googled “cake server with prongs” and found Jessica Reed’s website (“CakeWalk: Exploring Stories, History, and Identity Though Cake”), which is my new favourite place on the internet. In the post I found, Reed writes about this implement, “the cake breaker,” patented by Cale J Schneider in 1932. The cake breaker is specially designed to slice a cake without destroying it, essential in delicate cakes such as angelfood…

“Well, let’s make an angelfood cake,” I declared, determined—until I found the recipe had 12 eggs in it. Our eggs are free range and eggs are far far too precious for that. So no. I scoured my cookbooks for other options, and settled on an apple upside-down cake. Not the best cake for a breaker, I realized in retrospect, because it would have to slice through apples too. So not optimal, but it worked. We ate the second half of it this afternoon, and it was even yummier.

And the point of this, of course, is the amazing way that all roads (even udon!) lead to cake, however indirectly.

I mean, at least they do if you’re lucky…

January 14, 2017

25 Books, Including Mitzi Bytes

Today I was thrilled to find Mitzi Bytes in the paper, in grand company on a list of “25 Books We Can’t Wait to Read” in The Toronto Star. You can read it online here. Other books on the list I’m particularly excited about include new non-fiction by Sharon Butala, Marianne Apostolides, and fiction by Eva Crocker, Suzette Mayr, Eden Robinson, and, well, everything.