November 22, 2018

Margaret Laurence and Jack McClelland: Letters

It’s not typically a ringing endorsement when I tell you in November about the book that I’ve been reading since June, but this is no ordinary book. Margaret Laurence & Jack McClelland: Letters, edited by Laura K. Davis and Linda M. Morra has been one of the highlights of my literary 2018, a mainstay on my bedside which I’d pick up and read a couple of pages from every night. It begins with a letter from Canadian Publisher J.G. McClelland who sends a letter to a “Mrs. Laurence” in 1959 upon learning from a mutual friend that she’d recently completed a novel whose description sounded like something he’d be interested in. “I would be delighted if you would let us have the opportunity to consider the manuscript,” he writes.

It’s not typically a ringing endorsement when I tell you in November about the book that I’ve been reading since June, but this is no ordinary book. Margaret Laurence & Jack McClelland: Letters, edited by Laura K. Davis and Linda M. Morra has been one of the highlights of my literary 2018, a mainstay on my bedside which I’d pick up and read a couple of pages from every night. It begins with a letter from Canadian Publisher J.G. McClelland who sends a letter to a “Mrs. Laurence” in 1959 upon learning from a mutual friend that she’d recently completed a novel whose description sounded like something he’d be interested in. “I would be delighted if you would let us have the opportunity to consider the manuscript,” he writes.

Three weeks later, Margaret Laurence sends her reply. along with her manuscript for This Side Jordan, and so a literary partnership was born, between one of Canada’s greatest writers and McClelland, of McClelland and Stewart, the iconic Canadian publisher. And what a thing to watch, to read—the camaraderie developing between them, Laurence finding her voice as a writer, McClelland’s nurturing of and respect for her talent, which continues through the book entire. By November 1960, they’ve dropped formalities and are “Jack” and “Margaret,” and they spar, and they gossip, and they worry for each other, and support each other, and their letters tell a great of the story of Canadian literature and publishing in the second half of the 20th century (which seems just as perilous and depressing as it is in the 21st, fuelled by passion and no cash. “The market for fiction is so bad,” McClelland writes Laurence in 1964).

She writes to him in 1965, “I have finally managed to get a novel finished, but do not know yet if it’s any good or not.” That novel was A Jest of God, which McClelland finally reads and responds to by telling her, “The thing that continues to amaze me about your writing, Margaret, is that you improve with everything you write.” I adored so many parts of this book in the specific, like when Laurence coerces McClelland into creating an LP to release alongside The Diviners, which was so not his jam and much more trouble than it was probably worth. Or when McClelland is speaking to a group of English teachers and railing against Alistair MacLean (“one of the worst writers in the world”—what a distinction!) and the teaching of his works in Canadian high school classes, and then one of the teachers responds with “here you have been complaining about the censorship of The Diviners and, at the same time, you are attempting to censor Alistair MacLean.” McClelland closes the anecdote with this: “It’s a crazy fucking world.”

I also really loved the story of Margaret Laurence’s trip to the Writers Development Trust fundraising dinner in 1982, mostly because I often find being an author in public is often an exercise in various humiliations (see my friend Rebecca Rosenblum’s recent post “Indignities”). There were various complications at this particular dinner, particularly involving Margaret Laurence having to wait for a long time in a stifling corridor with nowhere to sit down or get a drink, and then when she finally enters the event and arrives at her table, she discovers that her table is…empty. The businessman who bought her table is late, and then when he finally shows up, he spends 20 minutes talking to Pierre Berton, and he also neglected to invite anyone else to sit at their table. It’s agonizing, and hilarious, and so many of us have been there.

By 1986, however, the dust has settled enough that McClelland dares to invite Laurence to another fundraising dinner for the Writers Development Trust, but this time the party is in her honour, and he’ll even host it in Peterborough so she won’t have to travel, and she’s even in agreement. But in September of that year, he receives the news that Laurence has terminal cancer, and he writes to her immediately: “Funnily enough what catches me at this particular moment is that I wish to God I could write. I would like to write you such a superb letter that it would enchant your and enrich you and support you through whatever the months ahead have to impose on you. I just don’t have that gift [or] skill—the one in the world that I admire more than any other.”

Laurence would die the following January, and I must say I have some vague idea of how hard that must have hit McClelland, how much he must have missed her, because I could have read this book forever. And possibly I will.

November 21, 2018

Lady Franklin of Russell Square

There is such a thing as a “[John] Franklinophile,” and I am not one, but still, Erika Behrisch Elce’s novel Lady Franklin of Russell Square delighted me. Written as a series of items discovered in old scrapbooks at Jane Franklin’s childhood home years later by a charwoman, the novel comprises news clippings of stories concerning the search for Franklin, who was presumed missing in late 1847, and also letters Lady Franklin had written for her husband from 1847 to 1857, the years during which went from imminently awaiting her husband’s homecoming to a gradual acceptance that he was not coming back. Not that she ever gives up home completely—she continues to use whatever money she can access to purchase ships and send out search parties, and she continues to engage the government in Britain to continue their search for Franklin’s party, and she solicits aid from abroad as well. No, she is not content to be “the Penelope of England,” as she was called in the press, and she doesn’t go for needlecraft. Instead, she consults maps with the same fervour her explorer husband must have (and the reader gets a sense that they were well matched in their thirsts for adventure), and reads the papers, and lobbies the government, and spends her time among the flowers of nearby Russell Square, with whose gardener she has developed an affinity.

There is such a thing as a “[John] Franklinophile,” and I am not one, but still, Erika Behrisch Elce’s novel Lady Franklin of Russell Square delighted me. Written as a series of items discovered in old scrapbooks at Jane Franklin’s childhood home years later by a charwoman, the novel comprises news clippings of stories concerning the search for Franklin, who was presumed missing in late 1847, and also letters Lady Franklin had written for her husband from 1847 to 1857, the years during which went from imminently awaiting her husband’s homecoming to a gradual acceptance that he was not coming back. Not that she ever gives up home completely—she continues to use whatever money she can access to purchase ships and send out search parties, and she continues to engage the government in Britain to continue their search for Franklin’s party, and she solicits aid from abroad as well. No, she is not content to be “the Penelope of England,” as she was called in the press, and she doesn’t go for needlecraft. Instead, she consults maps with the same fervour her explorer husband must have (and the reader gets a sense that they were well matched in their thirsts for adventure), and reads the papers, and lobbies the government, and spends her time among the flowers of nearby Russell Square, with whose gardener she has developed an affinity.

I loved this book. The letters are funny and smart, and sometimes angry and disappointed, and give the reader a rich perspective on this nineteenth-century woman’s interior life. An interior life that must necessarily be fictional, however, because Lady Franklin herself would destroy much of her personal correspondence, journals and records before her death. But if anyone is qualified to try to put the pieces back together again, it’s Erika Behrisch Elce, a Professor of English at the Royal Military College of Canada and editor of Lady Jane Franklin’s selected letters, As affecting the fate of my husband, in 2009. And I’m fascinated to consider how this novel must have grown out of that project, and how it felt for an academic to be blurring the lines between fact and fiction as she does here—and what kind of an adventure must that have been!

The prose sparkles in this novel, the plot is riveting even as we already know the ending, but maybe the ending is not the point—it’s the waiting instead. There is so much nuance in these letters, and also plot going on deep below the surface, and Elce also provides a remarkable record of the constraints placed on a Victorian woman, particularly one without a husband, the very opposite of the limitlessness imposed on so many men of the same era.

November 20, 2018

What I’ve Been Reading

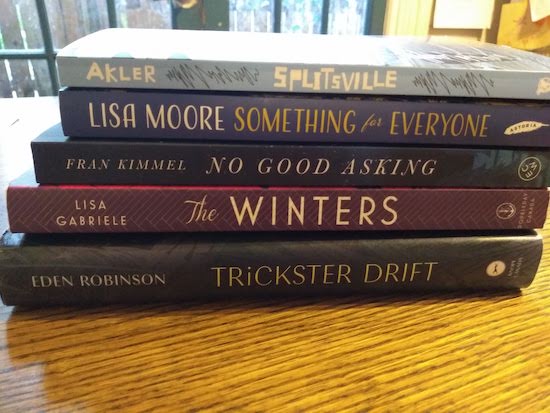

No Good Asking, by Fran Kimmel

No Good Asking, by Fran Kimmel

Kimmel’s novel is a perfect book for a winter’s night, the story of a cold world with warmth at its core. The Nyland family is close to breaking, estranged from each other even as they inhabit the same home. Eric has left his job with the RCMP and doesn’t quite know how to define himself outside of that role, plus he’s straining under the pressure of living with his elderly father after his mother’s death; Eric’s wife Ellie also wonders if coming to live with her father-in-law was the right choice, and she feels distant from her husband after years of disappointment and heartache after multiple miscarriages; plus, she is overwhelmed with caring for her youngest son, who has autism; and her teenage son is in trouble after crashing his grandfather’s car. And into this scene arrives Hannah, a girl escaping a traumatic home situation who needs a place to stay until proper foster care can be arranged. In connecting with Hannah, the family remembers also how to connect with each other, and while the novel is a little too lovely to be true (if only all children in care could have as little emotional baggage as Hannah does…), I forgave it because the other characters’ respective pain and sadness was so true and deeply realized—Kimmel does an incredible job of moving between all the characters’ different points of view. Plus, the scene that flashes back to Hannah’s mother and a trip they took together to the beach (which establishes Hannah’s solid grounding and makes clear that her late mother was such a good mother) is my favourite one in the book, rich with evocative writing.

*

Difficult People, by Catriona Wright

Difficult People, by Catriona Wright

I am such a fan of Catriona Wright, whose first book was the remarkable poetry collection, Table Manners, and I’ve been looking forward to her fiction debut, Difficult People, whose first story hit me like a brick. “Content Moderator” is the story of a failed academic turned moderator on a social media site whose days are spent having her should destroyed as she is forced to view one horrifying image after another until her faith in humanity is as gone as her soul is, and it’s dark and awful with the cleverest twist. It will leave you disquieted, as will “Lean Into the Mic,” about a stand-up comedian whose personal struggles are seeping into her act in destructive ways, and the piece is formatted as a monologue. A woman’s relationship with a prison inmate takes a turn for the (even more) dysfunctional. “Olivia and Chris” takes place in a not-so distant future where white North American women are outsourcing their pregnancy to Asian surrogates, but take pre-natal yoga anyway for an authentic experience. In the title story, a woman continues to chase corporate success after the suicide of her brother, who had stowed away in their parents’ basement and become a passionate Wikipedia deletionist. A friendship between two women fizzles out when one accuses the other’s stepbrother of raping her. And finally, in “Them,” a woman navigates her distance from a childhood friend/roommate who has come out as transgender, which only exacerbates the usual coming-of-age struggles of friendship anyway. These are stories that are singular, and Wright has such an eye for detail, a knack for character and nailing a particular point of view, and for rendering the ordinary as strange and baffling as it actually is.(This book also makes a nice companion for Emily Anglin’s The Third Person, which I read in October.)

*

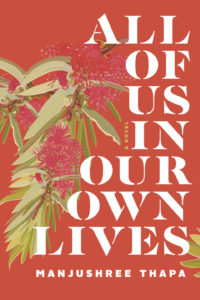

All of Us In Our Own Lives, by Manjushree Thapa

All of Us In Our Own Lives, by Manjushree Thapa

And I had the pleasure of reading Manjushree Thapa’s novel All of Us In Our Lives for Quill and Quire:

“First published in India in 2016 (and re-edited for publication in Canada), this is a novel that – as Gyanu is urged to do by a colleague – “look[s] at the world through a wide-angle lens.” Fitting for a story about cosmopolitanism, Thapa employs astral imagery and the connections between her characters create a kind of earthbound constellation. It is an ambitious project, drawing lines across continents, between cities and villages, and between people of different social standings and backgrounds. It works because characters’ experiences don’t map onto each other exactly, leaving room for complication and ambivalence.” (Go here to read the entire review.)

November 19, 2018

A Hat Like That

Millinary grief: It’s a thing. And you would think that mere hours after having listened to a radio interview with a woman whose child had died after she forgot him in her car, I would be able to refrain from going into a paroxysm of sadness from the realization that I’d lost my hat, but you’d be wrong then. Because relativity is a bitch, and it was not just any hat, which I know for certain now because I’ve tried three other hats in the 24 hours since, and none of them have measured up…to the specific proportions of my outsize head, I mean. But my Kyi Kyi hat always did, with a fleece liner and room for a ponytail even. After putting on a hat like that, all the others just seem paltry, scanty, barely worthy of the title “hat” at all—more like antimacassars for the head. And what’s the point in that?

There is so much to keep track of. This is what I was thinking on Friday evening when Stuart rushed Iris out of a movie theatre shortly before the credits because she was tired and ragey, and then I was charged with carrying out four winter coats when the film was finally over, along with mittens, neck warmers, and everybody’s hat. And I managed not to drop a single item, which I was particularly proud of, and then Stuart took Iris outside because she was threatening to vomit (she didn’t) and put on her coat there, and then they came back in—she only had one mitten. “No, we had all the mittens,” I was adamant. It was a point of pride, and then Iris started crying, and the theatre staff were promising they’d find it for her after the show was done, but I knew we’d had the pair and went outside to find the errant mitten lying on the sidewalk. Which was better than the time I had to go all the way back to the theatre at Yonge and Dundas Square to locate Harriet’s mittens, which turned out to have actually travelled home alongside her in her pockets, I suppose. But still: why do I spend so much time time enlisting cinema staff to locate missing mittens? What is it about the psychology of mittens anyway that gives them such a propensity for lostness? Such an endemic problem that they even wrote a nursery rhyme about it.

Hats too have a similar propensity, I suppose, as demonstrated in Jon Klassen’s loose-linked trilogy of books about missing hats and our the extent of our longing for these things. And while I would not eat a rabbit, if I could I would go to great lengths to track down my missing hat, which I think I must have left in a taxi on Saturday evening—except taxis apparently don’t have lost-and-founds, so it’s almost as thought my hat has ceased to be altogether. And I miss it desperately, even as I realize I’m lucky enough that I’ll be able to replace it. But not in that exact colour, and further, my thoughtlessness in losing it makes me feel like I was never really worthy of such a hat in the first place, plus I’ve lost my place in our family pom-pom squad. I miss my hat very much.

November 15, 2018

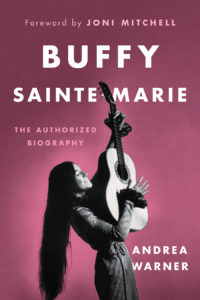

Andrea Warner and Buffy Sainte-Marie

“One of the first things that Buffy said to me was, “I’m not much of a linear thinker.” And this was kind of a soft warning. Her mind jumps around, and she goes backwards and forwards in time a lot, but I love it. I love following the sudden jolts, and she almost always comes back to a point, too, even if she left it behind four thoughts ago. It’s a very creative thought process, a vibrant and lively one. ”

“One of the first things that Buffy said to me was, “I’m not much of a linear thinker.” And this was kind of a soft warning. Her mind jumps around, and she goes backwards and forwards in time a lot, but I love it. I love following the sudden jolts, and she almost always comes back to a point, too, even if she left it behind four thoughts ago. It’s a very creative thought process, a vibrant and lively one. ”

November 13, 2018

Call Them by Their True Names, by Rebecca Solnit

While I really liked Rebecca Solnit’s The Mother of All Questions when I read it during the spring of last year, there was something about its tone that didn’t ring quite right. “There is a Rebecca Solnit book for every moment,” I wrote in my review, and there is indeed, but I think The Mother of All Questions was supposed to arrive in a different kind of moment, the kind that so many of us were expecting when America was on the cusp of electing its first woman president back in November of 2016. There was an optimism to the collection that seemed incongruous with 2017 in general—celebrating 2014 as a watershed in which women finally began to be listened to and believed when they shared stories of violence, for example. When just two years later a man who bragged about sexual assault would be elected to his country’s highest office—some watershed, I thought. Like most things in 2017, it was depressing and I wondered if maybe Solnit didn’t have her finger on the cultural zeitgeist after all.

18 months later, however, my position has shifted. I was revisiting the essay on 2014 (“An Insurrectionary Year”) the other week, and realized that 2014 was only part of the beginning of the project of changing the way we look at women, and violence, and power, and that while the backlash is full-on four years later, it’s only because the project is really happening. A watershed, of course, is never about just moment, and it’s about ideas that are out there now and can’t be packed away again. Of course, society is still struggling to reconcile all this, but it’s happening. Nobody ever said it would be easy, and it’s not as hopeless as I thought.

Which is the point of Solnit’s latest collection, Call Them By Their True Names, which has a freshness and vibrancy that her previous book (along with everything else in 2017) may have been lacking. Solnit has been busy since then writing for outlets including The Guardian and LitHub, but I think I encountered most of the essays in this book for the very first time, and she continues the same message she began with her collection Hope in the Dark in 2004, about the grounds for hope lying in the fact that nobody ever knows what is going to happen next—and 2016 only underlines that. She writes about Trump and Clinton—and on white left-leaning men and Clinton, “They saw the loss as theirs rather than ours and they blamed her for it, as though election was a gift they withheld from her because she did not deserve it or did not attract them.” About the men whose misogyny has since been made implicit by #MeToo, who turned out to be the same men who’d been defining cultural conversations for decades and had been instrumental in the way Hillary Clinton was presented in her presidential bid—and Solnit connects the voices missing in these conversations to the votes that are missing from democracy after years of voters suppression by various means. I loved her essay “Preaching to the Choir” in which she interrogates that metaphor—”And is there no purpose in getting preached to, in gathering with your compatriots? Why else do we go to church but to sing, to pray a little, to ease our souls, to see our friends, and to hear the sermon?”

She writes about climate change, the prison industrial complex, gentrification in her native San Francisco, the fight to remove Confederate statues, the meaning of the protests at Standing Rock, and also, as always, about hope. The final essay in the book is “In Praise of Indirect Consequences,” which brings me back to 2014, and 2017, and how you never really know what’s going to happen, the hope implicit in uncertainty. “Hope is a belief that what we do might matters an understanding that the future is not yet written.” She writes that she did not anticipate and was “moved and thrilled and amazed by the strength, breadth, depth, and generosity of the resistance to the Trump administration and its agenda.” But she is concerned it might not endure:

“Newcomers often think that results are either immediate or they’re nonexistent…This is a dangerous mistake I’ve seen over and over. To see where we are, you need a complex calculus of change instead of the simple arithmetic of short-term cause-and-effect.”

And then: “The only power adequate to stop tyranny and destruction is civil society, which is the great majority of us when we remember our power and come together.”

November 9, 2018

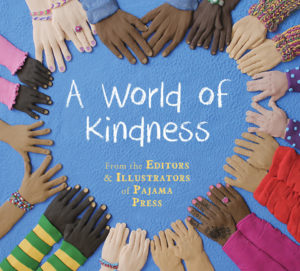

A World of Kindness

The superhero of my day today was the woman behind the counter of the Second Cup coffee shop where I was working this morning who engaged with every customer like she was happy to see them, who helped at least two elderly customers with fine motor tasks they were struggling with, and you could tell that for some people their conversations with her were the best parts of their days. She was just base level kind to everyone, and I thanked her for it when I finally left, because I liked the world a little bit better due to the fact that she was in it. Hers were little gestures, but they mean so much, and it’s how it all adds up that really matters, which is the point of a new picture book I love, A World of Kindness.

The superhero of my day today was the woman behind the counter of the Second Cup coffee shop where I was working this morning who engaged with every customer like she was happy to see them, who helped at least two elderly customers with fine motor tasks they were struggling with, and you could tell that for some people their conversations with her were the best parts of their days. She was just base level kind to everyone, and I thanked her for it when I finally left, because I liked the world a little bit better due to the fact that she was in it. Hers were little gestures, but they mean so much, and it’s how it all adds up that really matters, which is the point of a new picture book I love, A World of Kindness.

In a note inside the book, Pajama Press Publisher Gail Winskill writes that the idea for the book was born when her three-year-old granddaughter asked her one day, “Nana, how can I be kind?” Dedicated to the memories of Fred Rogers and Ernie Coombs (Misters Rogers and Dressup, respectively), the book has us to begin to contemplate that question, and makes some suggestion toward answers. “Do you wait your turn?/ Will you help someone younger…/or older?” Each page features art by Pajama Press’s acclaimed illustrators, some from previous books and others original (and my children were excited to see illustrations from books they’ve loved before!). Being gentle with animals, saying please and thank you, helping shy friends join in, watching over those who need it. “Will you be a friend to someone new?”

The ideas are simple, but they’re also transformative and profound, and the depth and diversity of illustrations on this book provide another layer of richness, making A World of Kindness a deeply meaningful read. Even better: royalties from the book will be donated to Think Kindness.

November 7, 2018

More Fall Book Picks

So many Fall Books to talk about this year that I had to do an extra instalment of my books column on CBC Ontario Morning. You can listen again to my recommendations on the podcast here (I come in at 46.00).

November 6, 2018

Publishing a Book is Not a Catapult

Publishing a book is not a catapult, unless you’re someone very lucky, and even if you are, I would imagine that even successful authors still have to contend with ordinary things like laundry, dry skin, and busses that don’t come. I’ve heard it on record that even the bestsellers show up at events and end up reading to empty rooms. Probably not as often as the rest of us, but still. But even though publishing is not a catapult, sometimes it is indeed just like a trampoline. Tomorrow night I get to show up at an awards ceremony and present a $10,000 cheque to the winner of the Journey Prize. And it’s funny to fit this into the context of ordinary experience, as in my husband will be taking our children to piano lessons tomorrow so I can be at the ceremony in time for the mic check, and afterwards we’ll both have to make the kids’ lunches. Or this: after spending days fretting about the fiction market and my future as a novelist, I get to fly away on an airplane to a literary festival where people bought tickets to hear me (and others) speak, and bought my books and requested I sign them. On Monday morning I took my children to school, but on Saturday people were asking for my autograph. By which, I mean, they wanted me to sign my novel, but it’s still the same thing. I feel very fortunate to have had a busy literary fall, especially since my book came out eighteen months ago. The life of a book is long, it’s true, and I’m so grateful to everyone who has worked to keep it going.

I had the most wonderful time in Sudbury on the weekend at their Wordstock Literary Festival. As Kim Thuy said to me as we were waiting at the airport, you know you’re a big deal when you get invited to a festival in a smaller city or town, because it’s amazing that they’ve even heard of you. And I know I’m not even a big deal, but it was sure nice to get to be in the company of Kim Thuy, and to meet so many readers and writers and bring books to life through great conversation. (I also got the chance to hang out with the amazing Danielle Daniel and see her gorgeous mural in person, and it was one of the best parts of an excellent weekend.) As always, I bow down to literary festival organizers, those tireless people who are usually volunteers and who pull off miracles every time. I feel so lucky for the chance to do authorial things, and take none of it for granted.

Publishing a book is not a catapult. I knew this, of course. The week before my novel came out I did a talk at a writers’ group and talked about how important failure had been to my process, about the novel I’d written ten years before that never was published, about the things I’d written that had turned out to be stepping stones to my success. “And there will always be some way to feel like you’ve not yet arrived,” I remember saying. “Maybe the book is not a bestseller, or it is a bestseller, but only for five weeks, or it’s a bestseller for months, but wins none of the prizes,” and on and on, the litany of ways for an author to feel unsuccessful. Maybe you’ll be giving a talk and nobody comes, and then the next time you give a talk and lots of people come, you’ll still be thinking about the last time. Since my book came out, many kind people have remarked upon how well everything seems to be going, how successful the book is: “I see it everywhere.” Like, all over my Instagram feed. But still. I’ve stopped correcting those people though, offering to clarify things, to underline all the ways in which I don’t measure up. I have decided that appearing successful might be the closest I ever come to being successful, and maybe there’s not even a distinction. Failure continues to be integral to my process, even though I was secretly hoping I was done with it when I gave that talk eighteen months ago. I have a feeling I’ll only ever be done with failure when I’m dead, but at least it’s never not been useful.

November 6, 2018

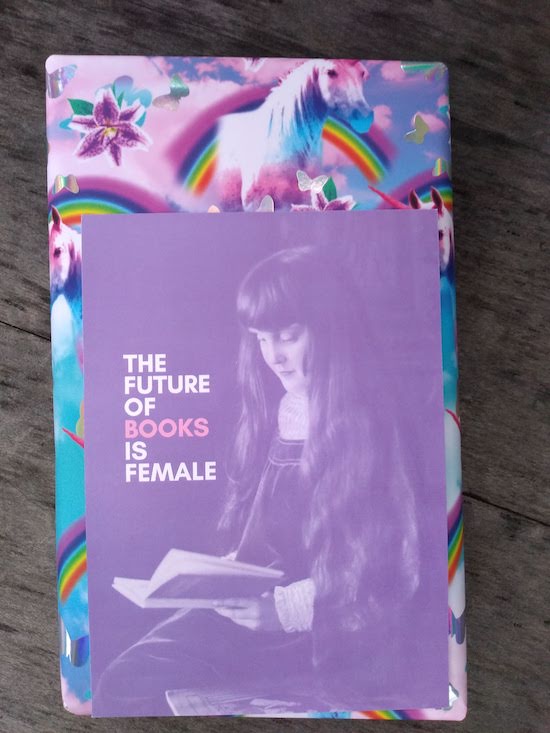

The Future of Books is Female

In this moment when so much seems dark, the light tends to shine even brighter, or maybe it’s just that I’m looking for it, but does the distinction even matter? It all began with a tweet thread, I think, when the editor of The Paris Review joined the parade of men who’ve lately been called out for sexual misconduct and when the editorial history of the magazine was being chronicled, one vital detail had gone amiss. “I’m going to show you how a woman is erased from her job,” the writer A.N. Devers tweeted, and proceeded to tell the story of Brigid Hughes, who’d succeeded George Plimpton at The Paris Review after Plimpton’s death, after working at the magazine for her entire career. But out of respect for Plimpton, Hughes was billed as “executive editor,” Plimpton remaining on the masthead. And then a year later Hughes was fired, and thereafter The Paris Review’s second editor and first female editor was written out of its history. Devers would eventually write this story into an essay published at Longreads.

Plans for Devers’ Second Shelf Books venture had been in the works for a few years, apparently (and is just one of the many fascinating things that she’s been up to), but for me the link seemed quite direct to me from her work on re-establishing Hughes’ professional record to starting a business that champions under-appreciated books by women authors (“rare books, modern first editions, and rediscovered works…”), and I was so galvanized by her work on the former that I jumped on board to support the latter. I signed up for the Second Shelf Books kickstarter to support the project and receive a copy of their Quarterly, a gorgeously produced magazine that is a literary catalogue and a celebration of women’s writing at once—and then before time ran out upgraded my support so I would receive a surprise first edition from Second Shelf. And it has been a pleasure to watch from across the ocean as Devers’ vision has become reality, the funding drive a success, a profile in Vanity Fair among other coverage, and the online store expanding to be actual bricks and mortar.

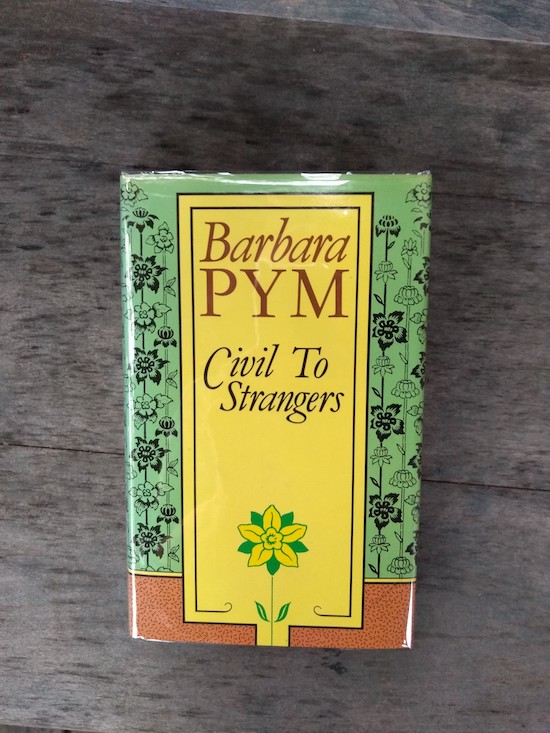

My copy of the Quarterly arrived a month ago, and I’ve deeply appreciated its aesthetic (marbled papers!), what it’s taught me about book collecting, and the writers I’ve been able to discover—for example, the first Black woman in South Africa to publish a novel was Miriam Tlali in 1975, with Muriel at Metropolitan. It has awakened my interest in book collecting for sure, and I’ve been pleased to discover I’ve already got a few first editions by women writers on my shelf, and now I’m on the look out for more—I found Carol Shields’ The Republic of Love at a used bookshop this weekend. It’s an opportunity, as Devers has explained, because books by women have historically been undervalued by book collectors (who’ve tended to be men), and therefore the investment is lower, but as more people begin to take notice, values will begin to rise. Or so it’s hoped, but regardless, I was overjoyed to receive my surprise first edition yesterday, carefully chosen after I’d completed a short survey online of my favourite authors. Wrapped in unicorn paper AND bubble wrap, so my children were squealing, and I got in on it too when I realized which book I had gotten. The hardcover Barbara Pym Civil to Strangers, a collection of stories and fragments published after her death. Could it be more perfect? And who knew there was a whole other reason to buy books that I hadn’t even considered? But I’m hooked now, and excited for the future of Second Shelf Books.