December 10, 2018

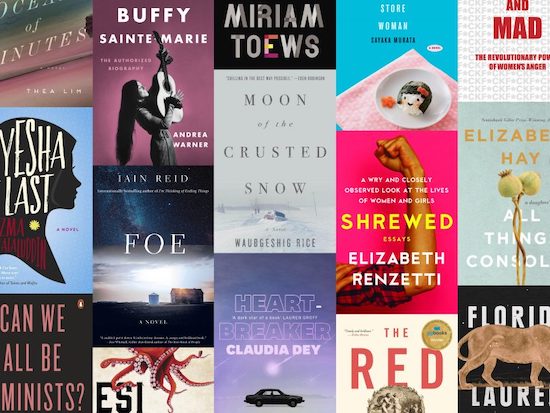

Chatelaine: Books of Year

I cannot overstate the pleasure I had being tasked with creating Chatelaine’s 2018 Books of the Year last, and how pleased I am with how it turned out. You can read the whole list here. And lucky me, I also got to help create the Books of the Year list at 49thShelf—there is definitely some overlap. And stay tuned for the Pickle Me This Books of the year list, coming up sometime later this week.

December 7, 2018

Owls Are Good at Keeping Secrets, by Sara O’Leary and Jacob Grant

One of my favourite kids’ books this year, a book with a wonderful premise and an execution just as good, is Sara O’Leary’s latest picture book, illustrated by Jacob Grant, the fun, clever and adorable Owls Are Good at Keeping Secrets—and of course they are! It just makes perfect sense, along with “Elephants are happiest at bath time” and “Jellyfish don’t care if you think they look funny when they dance.” And Z is my very favourite of all the alphabetized animal facts appearing in this whimsical abecedary, but I’m not going to tell it here, because that would be a spoiler. Of course, “Raccoons are always the first to arrive for a party,” but did you know that “Narwhals can be perfectly happy all alone”? And just wait until you get to U, which I’m going to let you discover by yourself, but I’ll trust you’ll find it as delightful as I did. The whole thing is good, O’Leary’s pitch perfect character details enriched by Grant’s illustrations, which manage to be cute and stylish at once. Even those who know their ABCs are likely to find this book absolutely enchanting, so while it’s an excellent pick for a Christmas gift for that someone little on your list, it will go over well also for those who are a little bit taller.

December 5, 2018

New Books on the Radio

I just can’t stop with the 2018 new releases, but one after another continues to wow me, so I’m very pleased by the opportunity to talk about five more of them this morning on my CBC Ontario Morning books column. You can listen again here—I come on at 41.30.

December 3, 2018

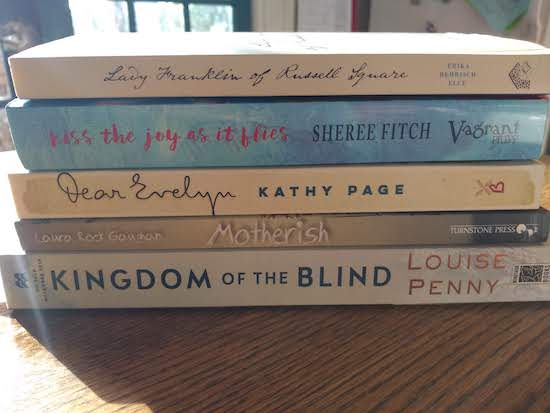

Dear Evelyn, by Kathy Page

Dear Evelyn, by Kathy Page, is a novel so good that last night I was full of nostalgia because it had been a whole week since I was reading it. And I was reading a very good novel last night too, but still, I was sorry to have been a whole seven days away from the remarkable experience of having been absorbed in Page’s award-winning book, which I read in two two-hour sittings. It’s the story of a marriage, the story loosely inspired by letters between Page’s own parents, some of which actually appear in the novel, making authorship an interesting collaborative endeavour. Beginning with the birth of Harry Miles, who grows up between the wars in London, the reader aware of the inevitability of his trajectory toward battle himself. But first, Harry meets Evelyn on the steps of the Battersea Library, and they fall in love with the same urgency as the world’s preparation for war, another kind of unreality. They spent most of the first years of their marriage apart, as Harry takes part in training and departs for war in North Africa. Seemingly-pivotal scenes—their wedding, Evelyn’s first pregnancy, the birth of their daughter—take place outside the narrative while Page focusses on the quotidian instead, the ordinary dailiness that Harry so longs for when he is away at war and longing for his wife.

Dear Evelyn, by Kathy Page, is a novel so good that last night I was full of nostalgia because it had been a whole week since I was reading it. And I was reading a very good novel last night too, but still, I was sorry to have been a whole seven days away from the remarkable experience of having been absorbed in Page’s award-winning book, which I read in two two-hour sittings. It’s the story of a marriage, the story loosely inspired by letters between Page’s own parents, some of which actually appear in the novel, making authorship an interesting collaborative endeavour. Beginning with the birth of Harry Miles, who grows up between the wars in London, the reader aware of the inevitability of his trajectory toward battle himself. But first, Harry meets Evelyn on the steps of the Battersea Library, and they fall in love with the same urgency as the world’s preparation for war, another kind of unreality. They spent most of the first years of their marriage apart, as Harry takes part in training and departs for war in North Africa. Seemingly-pivotal scenes—their wedding, Evelyn’s first pregnancy, the birth of their daughter—take place outside the narrative while Page focusses on the quotidian instead, the ordinary dailiness that Harry so longs for when he is away at war and longing for his wife.

And long for her he does, resisting temptation from other women when he’s far from home, and when he returns and settles into civilian life, the attraction between them is still strong. It’s not that this is a love poorly thought out, marry in haste, etc, but rather that life is long and love is complicated. And what is so astounding about the novel is how Page manages to show that complicatedness without compromising either of her characters. She shows how love and marriage can turn into something else as husband and wife continue to become more and more themselves as they age. It’s not that Evelyn changes—it’s that she never does. That strong personality that Harry continues to admire in his wife for so many years becomes a force that eventually pushes him out of his home, and the force is devastating—and yet he still continues to love her. And Evelyn herself, who is indeed herself but to a fault, and how her character traits borne out of struggle and deprivation during her childhood eventually leave her utterly alone. No wrenches need be thrown into this plot line, is what I mean. Or maybe what I mean is that that’s just what life is, a wrench. And characters themselves are just along for the ride, for better or for worse.

Dear Evelyn has a wonderful, effortless sweep, moving its characters from their hearty youth on to their nineties, including just the right details to show how the world is changing around them. Here, the novel benefits from Page’s experience as a short story writer, which is reflected in the novel’s episodic structure, the ease with which it moves from scene-to-scene and accumulates story without becoming bogged down. Short story writers are expert at efficiently fitting big ideas into small packages, which is how—in just 300 pages—Page is able to contain a century; two wars; two fully realized, flawed and complicated people; a rich and tumultuous marriage; so much love; and the pride, rage and resentment that keeps so much from ever being properly expressed.

November 30, 2018

The Zombie Prince and Mustafa

The Zombie Prince, by Matt Beam and Luc Melanson

The Zombie Prince, by Matt Beam and Luc Melanson

The first time we read The Zombie Prince, I was entranced by it, its puzzles and strangeness, how curiously it was framed, but the rest of my family weren’t so into it. “I didn’t get it,” they said, but I insisted, that this was a book that was special, that this was a book about boys and their feelings and the powers inherent in being sensitive. So we read it again, and they started to get it, liked the book as much as I do. I book that invites plenty of questions, which is why reading it again and again is worthwhile. “Why did Brandon tear up the flower?” I asked them tonight, and they speculated. This book isn’t breezy and is not a one-off, and runs the risk of being just a bit too subtle, but the illustrations are fun and appealing and the ideas of zombies and vampires are attractive enough to make a reader pick up the book a second time. This is a book with undercurrents, and the discerning reader will be able to put the pieces together. The discerning older reader will also be able to understand the implications of Brandon’s classmate having called him a “fairy,” and that this is a story with big implications. I appreciate its lack of obviousness, and that this is a book about boys and feelings that isn’t cheesy, or preachy. It’s expansive, like all the best books are, and isn’t afraid to ask its readers to think.

*

In her latest picture book, Marie-Louise Gay moves from her worlds of flying cats and a brother and sister in bucolic idylls to a different kind of reality, although it still comes with her characteristic whimsy. The title character in Mustafa is a young boy who has moved with his family away from an old country he still dreams of. “Dreams full of smoke and fire and load noises.” Lonely, he plays alone in the near near his new home, and takes in his new surroundings—shiny red bugs with black spots on their backs, trees whose leaves mysterious turn orange and red. “He sees two small animals jumping from branch to branch, They bushy tails wave and curl in the air. They chatter like monkeys.” There’s also a girl who walks a cat on a leash, and Mustafa is fascinated by all of it, but the girl in the particular because he fancies a friend. He asks his mother if perhaps he’s invisible. ‘”If you were invisible, I couldn’t hug you, could I?” answers his mama.’ But then one day the girl gestures for him to follow her, and they go together to watch fish in the pond. And Mustafa doesn’t feel invisible anymore, which makes for a really nice story about a refugee’s experience, but also an interesting exercise in seeing our homes from other people’s points of view, what we all look like from the outside, and how much it means to be invited in.

November 29, 2018

Gifts

There comes a point when one’s books enthusiasm reaches a certain height at which people just stop giving you books altogether. Because you’ve probably read it already, or if you haven’t, there’s a good reason why not, and either way, you’re probably so overwhelmed with books already that you’re hardly in need of another. And I lament this, the loss of books wrapped up with a bow, because books have always been my favourite gifts to receive. But at the same time, yes, I probably have already read it, or there’s a good reason why I never did. Because part of being a books enthusiast is possessing a very defined sense of what you don’t like too, for better or for worse.

There comes a point when one’s books enthusiasm reaches a certain height at which people just stop giving you books altogether. Because you’ve probably read it already, or if you haven’t, there’s a good reason why not, and either way, you’re probably so overwhelmed with books already that you’re hardly in need of another. And I lament this, the loss of books wrapped up with a bow, because books have always been my favourite gifts to receive. But at the same time, yes, I probably have already read it, or there’s a good reason why I never did. Because part of being a books enthusiast is possessing a very defined sense of what you don’t like too, for better or for worse.

So I relish those rare occasions where it all works out like serendipity, like the time my friend Jennie gave me Catherine O’Flynn’s What Was Lost after I had my first baby. It was one of the best gifts I’ve ever received, an acknowledgement of my identity as a person who was not only a mother, who still deserved something for herself, and could retain an element of who she was before the baby came. Also, because when somebody gives you a book, they give you a world.

At Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge, they’ve had mystery books wrapped in brown paper so that the costumer doesn’t’ know what they’ve got until they’ve bought it. Risky indeed—but then that was how I ended up with Herman Koch’s The Dinner a few years ago, a book I would never have bought on my own terms, but ended up really appreciating.

It was such a good experience that not long ago when I ended up in another bookstore (that shall remain unnamed) I was eager to lay down some cash for another mystery book. And once I bought the book, I was reluctant to even open it, for the mystery to be solved, for the anticipation was actually the best part: what was I going to get? What unknown world was I about to discover? And so imagine my disappointment then when I finally unwrapped my package and the book turns out to be The Fucking Pilot’s Wife by Anita Shreve, an Oprah’s book club pick from 1998, and I think I even read it then, but have no memory of it. A book that every single second-hand bookstore on the planet has at least twenty copies of, willingly or otherwise, and the only way to get anybody to buy them is to wrap them in brown paper. They saw me coming from miles away…

My faith in bookseller picks was restored a couple of weeks ago, however, when I picked up Let Me Be Like Water, by S.K. Perry, purchased in the summer when we visited the wonderful A Novel Spot Books in Etobicoke. It wasn’t wrapped in brown paper, but it might as well have been, because I knew nothing about it, but it was one of their picks of the year and I mostly bought it because they are very good at selling books there—they made it hard to say no. And then a few weeks ago after a reading rut, I finally picked it up, and I loved it. I was reading it on the Saturday morning and for some reason my paper hadn’t been delivered, and I didn’t care, because it meant I could read the novel all morning while I drank my tea and the sun poured into my kitchen. A book it took an expert reader—a bookseller—to connect me with. A kind of magic indeed.

November 28, 2018

A Spark of Light, by Jodi Picoult

“Oh my gosh, does Jodi Picoult ever know how to write a novel,” I said to my husband the other night on the tail end of having read her latest in a single day. But of course she does, having written twenty-three of them, and has a reputation for bestsellerdom as well as a penchant for melodrama. I’d started one of her novels years ago—I think it was Nineteen Minutes, about a school shooting, and decided it wasn’t for me, and I actually hadn’t given Jodi Picoult a lot of consideration since…until A Spark of Light, set against a hostage taking at a Mississippi abortion clinic. And we all know there is nothing I’m more interested in than a good pop-culture abortion narrative, so I put this book on hold at the library, and it turns out that now I know what everybody else knows, which is Jodi Picoult is really extraordinary.

“Oh my gosh, does Jodi Picoult ever know how to write a novel,” I said to my husband the other night on the tail end of having read her latest in a single day. But of course she does, having written twenty-three of them, and has a reputation for bestsellerdom as well as a penchant for melodrama. I’d started one of her novels years ago—I think it was Nineteen Minutes, about a school shooting, and decided it wasn’t for me, and I actually hadn’t given Jodi Picoult a lot of consideration since…until A Spark of Light, set against a hostage taking at a Mississippi abortion clinic. And we all know there is nothing I’m more interested in than a good pop-culture abortion narrative, so I put this book on hold at the library, and it turns out that now I know what everybody else knows, which is Jodi Picoult is really extraordinary.

Obviously, her narrative being constructed around a hostage stand0ff, Picoult’s melodramatic bent continues, and I was wary of her reputation “for writing about both sides of polarizing issues.” Frankly, we’ve got far too much of “both sides-dom” going on in our discourse at the moment, which results in justifications for fascists being given wide-platforms, sympathy for white nationalists, and slow, terrifying and far from grass-roots growth of the anti-abortion movement in Canada. Now is hardly the time to stand on the middle, to sit on the fence, etc, instead at this dangerous political moment it’s more important to take a stand than ever, to draw a line.

The thing is, of course, that abortion isn’t actually polarizing after all, and the only people who might suppose it is are the people who’ve only ever considered abortion in the abstract or as a thought-exercise. But for those of us with lived experience of abortion and those who perform abortions as part of their medical practice, abortion is very much a space in between, where women who have abortions tend to be mothers already, where almost all abortions after 12 weeks are for very much wanted pregnancies whose severe and unviable fetal abnormalities, where women who miscarry and have abortions are sometimes the same women, where women who have abortions go on to have the families they wanted when they’re ready for it—and where “pro-life” women can find themselves on the other side of the debate when they’re faced with complicated or unwanted pregnancies. As Picoult writes in her novel’s Author’s Note: “Laws are black and white, The lives of women are a thousand shades of grey.”

And she shows so many of those shades in A Spark of Light, which begins with a paragraph on how Mississippi abortion clinics had had so many restrictions placed upon them (“the halls had to be wide enough to accommodate two passing gurneys; any clinic where that wasn’t the case had to shut down or spend thousands of dollars on reconstruction…”) so that those remained were rare as unicorns. On the periphery of the novel is a young girl who was unable to obtain an abortion due to age restrictions and other legal hoops to jump through so that she ended up administering a pill ordered from the internet, and when she’s brought to the hospital after bleeding profusely, police are called and she’s arrested for murder. The pregnant women in the clinic when the gunman breaks in are from all kinds of different backgrounds and in various situations, and some of them aren’t pregnant, because abortion is only one kind of health care administered by women’s health clinics. And what I loved most about the novel is that even the characters who aren’t pregnant or haven’t had abortions have had their lives touched issues of reproductive justice—sometimes without even knowing it, which is often the case in a society where things like rape, women’s sexuality and abortion are taboo.

The novel was gripping, and here is where I saw Jodi Picoult’s plotting prowess in action—the twists kept coming right to the end. And the novel is set in reverse chronological order, even, which makes the twists at the end all the most astounding from a craft standpoint, and none of them were cheap either—I really appreciated that. The characters were rich and fully developed, and this is where the novel was wonderfully challenging to me, in how Picoult humanizes a character who’s actually a pro-life protestor gone undercover to record illegal practices inside the clinic (she doesn’t find any, btw) when the gunman arrives. It turns out not to be about “both sides,” but instead understanding one’s humanity and motivations, in making characters real and multi-faceted, and learning where someone is coming from. Which doesn’t mean they’re right, and Jodi Picoult shows that they’re definitely not (fact: the best way to limit abortion is to have liberal abortion laws, access to birth control and sexual education. fact: making abortion illegal drives abortion underground and puts women at risk. fact: there has been abortion everywhere and always. fact: opposition to abortion is fundamentally an opposition to women’s sexuality). It remains ever important for us to listen to and learn from each other.

This is the kind of novel that can change the world, because if it challenged my ideas about abortion, it will also challenge the mindset of someone whose ideas are different, to consider other points of view. To bridge a divide that grows ever wider as we all sit convinced of our righteousness, without considering that someone on the other side feels just as righteous as we do. (Picoult doesn’t include male pro-life activists in the novel, who are the more typical demographic actually. I suspect that she knows that their motivations and backstories are less interesting than their women counterparts, that they have less to teach us in this situation.) It’s also just a thoroughly terrific read with great characters and plotting, and facts and current events while not being too heavy on the research, and really good writing, apart from one unfortunate paragraph where a father makes a twist on that “one’s child being your heart outside your body” idea to talk about a child being like a soap bubble you carry on your palm while you run through an obstacle course, or something like that. But let us forgive the novel that has just one terrible simile, especially if it does all the other incredible things. After twenty-three novels, Jodi Picoult knows what she’s doing.

November 27, 2018

My 2018 Best Books That Weren’t Published In 2018 List

I have but one complaint about literary 2018, which is that I didn’t read enough books that weren’t new releases, but then when I think about all the new releases I never even got to, I’m not sure what else I should have done. I did my best, but still, it’s those back catalogue books that keep one’s reading life truly interesting, I think. I will attempt more of this in 2019, and in the meantime, here are some very good books I read in 2018 that were published in previous years.

*****

Joyce Wieland: A Life In Art, by Iris Nowell

Joyce Wieland: A Life In Art, by Iris Nowell

One of the biographies I read over the holidays, this was a fascinating look at the life of one of Canada’s most innovative and important artists.

*

Salvage the Bones, by Jesmyn Ward

Salvage the Bones, by Jesmyn Ward

Behind on the times here. I finally read Men We Reaped last year, which meant I had to read everything else by Ward. Salvage the Bones is masterful and devastating, essential reading for our times (and I also loved Sing Unburied Sing).

*

Life in Code, by Ellen Ullman

Life in Code, by Ellen Ullman

As I’ve found through reading and writing about blogging, women’s voices and experiences are so often missing from stories about the history of computers and technology. A coder since the 1970s, and also a fiction writer, Ullman has a singular voice and a unique perspective. I gave this book to my husband for Christmas but ended up enjoying the book as much as he did.

*

Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life, by Amy Krouse Rosenthal

Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life, by Amy Krouse Rosenthal

I can’t remember why I ended up taking a whole bunch of books by Amy Krouse Rosenthal out of the library in January/February, but I did and they were delightful, and this one reminded me of the mundanity of the early internet in the most extraordinary way.

*

The Ballad of Peckham Rye, by Muriel Spark

The Ballad of Peckham Rye, by Muriel Spark

I bought this book when we were on holiday in England during a snowstorm in March in a spiffy new edition, and it served to remind me that Muriel Spark is utterly strange and unfathomable, and brilliant.

*

The Handyman, by Penelope Mortimer

The Handyman, by Penelope Mortimer

Of all the Penelopes, Mortimer is my favourite, although I read her best-known and reissued The Pumpkin Eaters and failed to love it, but her others have delighted me, reading as fresh, contemporary, subversive and unafraid of darkness.

*

Behold the Dreamers, by Imbolo Mbue

Behold the Dreamers, by Imbolo Mbue

Everyone screeching about illegal immigration should read this book about the limits and challenges of people who are hoping to find their way to the American dream by any means necessary, the desperation of their plight. This was a novel that was rich with twists and surprises.

*

A View Of the Harbour, by Elizabeth Taylor

A View Of the Harbour, by Elizabeth Taylor

I read this during the last weekend in June when it was so hot I almost died, and it had been been sitting on my shelf for years, and I’m so glad I finally got to it. It was so Woolfian, almost uncannily like an inversion of To the Lighthouse.

*

What Alice Forgot, by Lianne Moriarty

What Alice Forgot, by Lianne Moriarty

Moriarty is a genius. I love her, and everything she does, and just because I exclusively read her books on vacation should not mean she does not get full points for character development and intricate plotting.

*

Everything I Never Told You, by Celeste Ng

Everything I Never Told You, by Celeste Ng

I must confess that I liked Little Fires Everywhere better than Everything I Never Told You, mostly because a book that things people never tell each other sets itself up to be full of weird unbridgeable gaps and it brought up too many questions for me as a reader. But it was still really, really good.

*

Moon Tiger, by Penelope Lively

Moon Tiger, by Penelope Lively

I reread Moon Tiger this summer after falling in love with it more than a decade ago. It was a contender for a best-of-the-Booker winner that went on earlier this year, and in this feature for the Guardian reading group, it’s discussed that the book was dismissed as “the housewives’ choice” when it won the Booker Prize in 1987. Lively is my other favourite Penelope, and it was a pleasure to be reminded of how huge and wonderful this novel is.

*

Conversations With Friends, by Sally Rooney

Conversations With Friends, by Sally Rooney

There was such hype for this novel that I must confess I was a bit disappointed when it didn’t blow my mind, but then blowing minds was never going to be what this book is about. Instead it’s subtle and quiet and most remarkable for the things the narrator is never able to articulate. I read it last week so I’m still thinking it over. Her new book is out here in the spring and even more hyped (nominated for the Man Booker Prize) so we will see what happens next…

November 27, 2018

Motherish, by Laura Rock Gaughan

True confession: I find debut short story collections to be a bit hit and miss, more miss than hit, actually, but Laura Rock Gaughan’s Motherish turns out to be one hit after another. The entire book cohering around ideas of being a mother and having a mother, and smart enough to know that within this “niche” are a million degrees of experience. Every story is distinct, sparkling in its own particular way. It begins with “Good-Enough Mothers,” about a woman whose wife travels for work while she stays at home with their children and ponders the neighbourhood, including the family across the road who run a tow-truck company, and the woman next door who lives with her ailing adult daughter, and the strange and disturbing ways that these households’ connect with each other. Notions of bad mothers and good mothers intermingle here, and everything is relational. This story’s tone is ominous, dark-undercurrents. In motherhood always, there will be peril, and you’ll have to read to find out where.

True confession: I find debut short story collections to be a bit hit and miss, more miss than hit, actually, but Laura Rock Gaughan’s Motherish turns out to be one hit after another. The entire book cohering around ideas of being a mother and having a mother, and smart enough to know that within this “niche” are a million degrees of experience. Every story is distinct, sparkling in its own particular way. It begins with “Good-Enough Mothers,” about a woman whose wife travels for work while she stays at home with their children and ponders the neighbourhood, including the family across the road who run a tow-truck company, and the woman next door who lives with her ailing adult daughter, and the strange and disturbing ways that these households’ connect with each other. Notions of bad mothers and good mothers intermingle here, and everything is relational. This story’s tone is ominous, dark-undercurrents. In motherhood always, there will be peril, and you’ll have to read to find out where.

“Maquila Bird” takes place in Mexico where a woman who works in a garment factory sewing jackets aims to escape her employers’ mandatory pregnancy test and hold onto her job just a little bit longer. In “Transit,” a pregnant woman who is uncertain of the terrain that lies before partakes in an eventful streetcar journey. “Let Heaven Rejoice” is the story of an oblivious church organist and the thoughts of those around her while the music plays, including her husband and children. “At the Track” takes place during the summer of 1975 (“The summer of 1975, my grandfather’s friends wore leisure suits in turquoise and moss and mulberry with patterned shirts left open a few buttons to reveal an overgrowth of chest hair…”) when a young girl is left in the car of her not-always-responsible grandparents while her single mother works nightshifts. In “The Winnings,” a woman’s fiancé wins the lottery and she starts to reconsider their future together. “Me and Robin” is narrated by a young girl who cares for her effeminate younger brother, although her feelings toward him are ambivalent.

“Masters Swim” is a strange but compelling story about swimming, and sisterhood. In “The New Kitten,” a woman’s job as a bank teller gives her a unique perspective on her husband’s infidelities as she tracks his accounts. “Leaping Clear” is about a woman nearing the end of her life who is visited by the ghost of the man who’d got her “in trouble” years before, and reveals the real story of what happened to him after he skipped town (and what happened to her when she said yes to another man who wanted to marry her anyway). “Woman Cubed” about a contortionist and her overbearing partner. “Mother Makeover” about reality TV show when mother drama gets ramped up to max. And finally, “A Flock of Chickens,” which I loved, about a teacher who gets into an ill-advised relationship with a colleague and ends up in a chicken coop, as you do.

Which is all the stories in the book, actually, which means not a dud among them, and I enjoyed reading this collection so much, its tautness, its polish, and wise perspective on characters’ lives. Stories that are never samey, but instead such a pleasure to behold, one after anther.

November 26, 2018

Good and Mad, by Rebecca Traister

“The ability to narratively flip the dynamics of aggression and abuse—to view the less powerful as a menace to the aggressors—has been key to how white patriarchal structures have persisted. It’s how police can systematically killed black people but when black people protest those killings with Black Lives Matter marches, those protestors can be called “terrorists” on the news, or a “hate group,” by the Republican pundit Meghan McCain. It’s why, when Baltimore resident Freddie Grey was hauled into a van by police in Baltimore in 2015 and taken on a rough ride that resulted in his death, multiple news reports asserted that the “violence started” when protestors threw rocks in protest of his killing, and now when he was murdered.

“The ability to narratively flip the dynamics of aggression and abuse—to view the less powerful as a menace to the aggressors—has been key to how white patriarchal structures have persisted. It’s how police can systematically killed black people but when black people protest those killings with Black Lives Matter marches, those protestors can be called “terrorists” on the news, or a “hate group,” by the Republican pundit Meghan McCain. It’s why, when Baltimore resident Freddie Grey was hauled into a van by police in Baltimore in 2015 and taken on a rough ride that resulted in his death, multiple news reports asserted that the “violence started” when protestors threw rocks in protest of his killing, and now when he was murdered.

The violence done by the more powerful entity—the police and the state—to the less powerful entity is often so normalized, so banal, so expected as to not even be discernible, not even visible. But angry resistance to that violence, coming from the less powerful and directed at more powerful, is automatically understood as disruptive, dangerous, electric. The upset of power dynamics creates chaos…

These structural assumptions are why calls for civility almost always redound positively to the oppressors, because incivility against the oppressed is not only so normalized, it is also so comforting that it can barely be detected as oppression; while even the most trivial challenge from the less powerful sets off alarms.”

—Rebecca Traister, Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger