February 26, 2019

Gleanings

- She’s spent a lot of her career thinking about the province she calls home, but her stories aren’t usually warm and nostalgic.

- On not centring menstruation around fertility.

- Irises really are a grand and whimsical bloom.

- I love how much these children want stories. A book is a spell.

- Many of my dreams are semi-nightmares but this one sort of snuck up on me and I don’t like it, even though I’m all for the experiment with narrative form.

- Definitely a great discovery, this is prickly strange reading.

- Looking for midwinter inspiration, I took Rob to our favourite flower store…

- The Starship Enterprise Editing Technique.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

February 25, 2019

Where I Find the Time to Read: The Post-Breastfeeding Edition

In 2015, when my youngest child was not quite two, I published a popular blog post called “Where I Find the Time to Read,” a list of ordinary occurrences disguising excellent opportunities to steal a moment with a book. Understandably, considering my life at the time, many of these occurrences revolved around breastfeeding, which I always found to be a tremendous reading opportunity (and never mind the risk of dropping a hardcover on my baby’s head—and she was fine). But now that it’s been a few years since I’ve breastfed anyone, I wanted to come back to that list, provide some update and revisions. Because of course you don’t need to be lactating to get that book read. The following are how I still manage to be reading all the time.

- A hammock of my own: I may not have a room of my own, but I have a hammock in my backyard set up all summer long in the shade of our silver maple tree. On sunny days, I’ll set up my children with a movie, and then head outside for hammock time, which entails at least an hour of uninterrupted reading, and the reading is ideal there. Everyone should have a hammock, whether metaphorical or otherwise.

- Be prepared: I’ve written about this before, about how I’ve gone to concerts, birthday parties, and even my own book launch with a book in my bag—because you never know when an opportunity for reading is going to arise. Pro-tip: If you’re nearly finished one book, make sure you pack another, and maybe a back-up in case the other doesn’t take. Second pro-tip: book sleeves are really, really great.

- I like my children to be well-rounded: My children are not enrolled in a huge number of extra-curricular activities, but the ones they are involved in permit me to read while they’re attending. I work extra hard at scheduling to make sure both children are busy at the same time so that I can read instead of entertaining the other. I read when they’re at Girl Guides, piano lessons, and swimming lessons, and I find it infinitely rewarding.

- There is no data on my phone: It’s much easier to scroll through feeds on my phone than it is to read, it’s true, but scrolling on my phone makes the time go by so much faster and in the end I have nothing to show for how I spent my half hour while my children were at swimming lessons, just say. But without data, I can only use the internet on my phone where WiFi is available, which (mercifully!) isn’t everywhere yet. It makes my phone less of a distraction and I get a lot of reading done.

- Frequent long baths: For me, a hot bath is like a hammock, an avenue to reading. The only real risk is getting into the bath and realizing that you’re not really into the book you’re reading, so I usually have at least two books piled up on my toilet seat so that there’s no possible reason why I might have to get out of the tub.

- I read for lunch: Going out for lunch with a book continues to be my favourite kind of date, my ultimate indulgence. Restaurant hostesses really do have to get over acting so surprised when a diner shows up for a meal solo though, and you don’t need to make it so awkward by taking away the glass and a cutlery. A good book is worthy of its own plate setting. (Also, when I used to work full-time, I ate my packed lunch with a book every day.)

- Public transit: Okay, I don’t take public transit on a regular basis (my primary mode of transport is walking, which is also a great excuse to read, except it’s winter now and it’s too hard to read while wearing mittens), but whenever I ride the subway, I’m reading a book, whether I’m holding onto a straphanger or sitting in an actual seat. (My biggest regret continues to be that reading on busses and streetcars makes me carsick.)

- I pack books in the bag en famille: While reading in front of people can be anti-social, there is nothing better than reading together. For long subway journeys, trips to the beach, or to the park, I bring books for everybody. The extra weight is worth it for the extra reading.

- I binge-read on my holidays: “How many books is too many books for a weekend away?” so goes the question on social media, captioned to a leaning tower of bookishness. But the question is absolutely rhetorical—there is no such thing as too many books. And I personally consider a holiday a bust unless I’ve managed to read at least a book every day.

- Going to bed early: There is a definite relationship between finding lots of time to read, and being a little bit boring. Once upon a time, when I wasn’t almost forty, I would read into the wee hours of the morning, but those days are gone now, particularly since I must now rise early every morning and go for a swim first in order to have the kind of day I want to have. (My inability to read while swimming continues to be one of my life’s great frustrations.) So now I tend to go to bed soon after my children do, and leave my phone far, far away, which had result in two solid hours of reading before I turn out the light. These days, this is really how I get most of my reading done.

- I stay in bed in the mornings: I do not go swimming on weekend mornings, and instead I roll over and turn the light back on and indulge in a chapter or two. Sometimes if I am lucky, someone will bring me tea. Sometimes my children will also come and visit, but eventually they go away, because watching someone read is very dull.

- My limited relationship with Netflix: The only thing I binge on is books—and tea. I like Netflix a lot, but only watch it on the weekends, and usually just an episode at a time. Which means there is always time to read, even on Fridays and Saturdays.

- I only read good books: What I mean by this is that I give up on books that aren’t working for me. I no longer read books that I think I “should” be reading if I really don’t think they’re appealing. I also have a trusted list of book experts whose recommendations I always listen to, all of which means that when I am reading, the activity is usually a pleasure. Which is absolutely the way it should be.

This post is part of a larger project I’m embarking upon this year which endeavours to make books and reading more accessible to the aspiring avid reader, that person who examines her bookshelves with guilt because she just can’t find the time to get all those titles read, never mind finish that novel for her book club. Stay tuned for more exciting things to come…

February 22, 2019

Why I Put My Children Online

Once in a while, some thoughtful person will ask my permission before posting a picture online—a Facebook page, a community website, their Instagram feed. And in response I always start laughing. “You go right ahead,” I assure this person. “After all, I’ve plastered both of them all over the entire internet already.”

For 18 years, I’ve been telling my life stories via blogging, and when I became a mother, I didn’t see a reason for things to be different. In fact, when my eldest daughter was born, I needed the communities of blogs and social media more than ever. It was through my blog that I puzzled my way through early motherhood, and found friendships and connections that made me feel so much less alone at a difficult time.

Of course, things became more complicated as my children grew, developing into individuals in their own right. I knew that they would be implicated in the stories I told, and so I exercised caution, asking myself, “Will this keep my child’s dignity in tact?” before posting a photo or an anecdote. Only once I ever fudged this, and this was when I posted a photo of my naked child’s bare bum as she played in a paddling pool on a rooftop. The backdrop was a cityscape—it was quite dramatic—and I figured that as you couldn’t see her face, she would come off from this fairly innocently.

But what about the pedophiles???, some worried parents will inevitably respond to this (and they did, in fact). To which I reply that while I do keep such nefarious individuals in the back of my mind, letting these people guide the way I operate myself online would be misguided. Regarding the internet as a place wholly apart from the world would be similarly wrong, and so instead I proceed with a spirit of openness with a sensible amount of caution.

Letting my children exist on the internet at their young ages is also a useful way to acquaint them with social media, which will presumably be a huge part of their lives in general when they are older, just as it is a huge part of mine. They are currently invested in how they appear on social media and on my blog, and are developing an understanding of how it all works, which will make them more savvy online operators when they’re ready to venture into the world without parental accompaniment.

For my older daughter in particular, I do ask her permission when I post images of her or write about her. (There are many photos I never posted, and stories that I’ve never told.) Although I also understand that the permission granted by a nine-year-old is dubious at best. But this is where the fact of me being her parent who is looking out for her interests comes in handy—it’s actually my job. And she trusts, and I trust, and her father trusts too, that I will make smart decisions that will also keep her safe—and preserve her dignity as well.

Of course, there will be mistakes and misinterpretations. Things will go wrong. Posts will be deleted. I hereby reserve the right to mess up, but to keep on learning too, rather than just simply forgo my children appearing in my online life altogether. (There are also indeed weirdo parents who blatantly exploit their children for YouTube notoriety, but maybe let’s not make this base-level parenting be the standard from which all our ideas and discussions about parenting begin.)

My biggest reservation with the expectation that women not share their images and stories of their children is that it implies that certain parts of a woman’s experience no longer belong to her once she becomes a mother. It reminds me of those 19th-century images of “ghostmothers” shrouded in black holding their babies in portraits. It’s not so far along the spectrum from a line of thinking that once a woman becomes pregnant, she doesn’t even properly belong to her body anymore and therefore someone else can be charged with her reproductive choices.

There is also a gendered element to this discussion, in which mothers often refrain from posting photos of their children and explain that it’s because of their male partner’s discomfort with social media. I find it strange and troubling that a man whose partner is active and literate in social media could not trust her to make smart choices in this space (often a feminized one) which he is less savvy about, and instead has the power to decide what she posts online.

While I acknowledge that a woman’s life is no longer just her own once she has children, I assert her right to maintain an existence on the internet (which these days is where a lot of life happens) that acknowledges her entire personhood—and motherhood is a part of that, if she desires it to be. The stories I tell about my children are their stories, but they’re also my stories too.

In my novel, Mitzi Bytes, my protagonist learns that while compartmentalizing one’s experience and maintaining a rigorous divide between online and actual selves seemslike a smart approach, ultimately it’s not sustainable. Living in the world is more complicated than that, both online and off it.

February 21, 2019

Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions, by Briallen Hopper

Of all the surprising realities I’ve lately found myself facing, none is more surprising than this one: On Tuesday night I stayed up long past my bedtime because I couldn’t stop reading an essay on Cheers. Right? The essay was “Everything You’ve Got,” from Briallen Hopper’s brand new essay collection Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions, about the joys of rewatching the show on Netflix and how it bridges her reality as an academic with working-class origins. It’s been a long time since I thought this hard about Sam and Diane, and the last time I did I was eleven years old or thereabouts, so the thinking has become a bit more deep and nuanced, but the essay was terrific writing about making your way in the world whilst in your ’30s, whatever you get up to when your dreams of Major League baseball stardom are all done.

Cheers, of course, is a show about friends, and so are most of the essays in Hopper’s collection, which I read over a weekend now named in our province “Family Day” in honour of the statutory holiday. Hard to Love serving as an appropriate balance, the idea that family needn’t be based in biology or marriage, but can be based in friendships instead, which Hopper doesn’t even make a case for because her experience demonstrates it plain as a fact can. The book’s opening essay is “Lean On: A Declaration of Dependence,” which you can read online here, and I loved it, a story about how there is nothing wrong with leaning on each other. “I’ll never stop singing along with Bill Withers. I believe we all need somebody to lean on. But sometimes it seems like there are two American creeds, self-reliance and marriage, and neither of them is mine.”

This book is a collection of so many of my own fascinations: “Pandora in Blue Jeans” is all about Grace Metalious’s author photo, which is followed by an essay on Shirley Jackson and domesticity. Barbara Pym is referenced more than once, and then “Tending My Oven” and there are recipes. She writes beautifully about her complicated relationship with her brother through the lens of “Franny and Zooey.” “Coasting” is about the network that emerged as she and a few others become caregivers for a friend with cancer. In “The Foundling Museum” and “Moby-Dick,” she writes about her desire to have a child, and how her chosen family have supported her in this choice and process. The final essay “Girls of a Golden Age” about her community in New Haven, and plans to put down roots and purchase her apartment building along with friends—but then along comes a job offer in New York. Goodbye to all that. And also, hello.

It turns out that Hard to Love just isn’t, and never more than when matters are messy and complicated. These are essays, beautifully written, rich and generous with twists and turns, and insight.

February 19, 2019

Gleanings

- I’ve had my fill of faux community consultations.

- I want to constantly renew my creativity in attempts, and tries, and blunders, and anonymity.

- …how often it’s the entire atmosphere of reading — current circumstances, personal life stage, other voices bumping alongside — that makes a particular book memorable.

- That’s really the richness and beauty of anthologies. There are debates going on, and some readers take sides.

- How much more robust would my education have been had I read more women, especially ones who were still alive?

- Little girls with mothers who are teachers-of-life grow up to be women who observe, taste, admire, explore, and appreciate.

- …and once I’m in the water, I wonder who that person was who had hesitated, so happy am I to be swimming back and forth and back again.

- There is something so satisfying in perusing other people’s bookshelves.

- They say one shouldn’t do a thing if one’s heart isn’t in it–but one probably also shouldn’t do it if the heart is too much in it.

- I realize that by using the term “chit-chat”, I’ve possibly belittled what this group has come to mean to me.

- How certain gestures, features, remain over time, in the intricate mathematics of inheritance.

- I do still adore The Stone Diaries and recently pressed it upon a student, and I can certainly see its imprint on this book.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

February 19, 2019

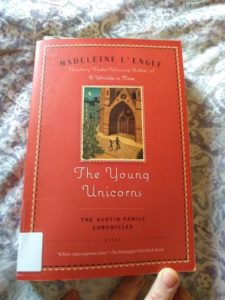

The Young Unicorns, by Madeleine L’Engle

My Madeleine L’Engle/Austins project continued this weekend when I read The Young Unicorns, the third book in the Austins series. A series that is all-over-the-place in the most interesting way, in terms of genre in particular. Because this book (whose narrative does not, in fact, include a single unicorn, in case you were curious) is a dark and plot-driven mystery, very different from the previous two novels which were episodic. It’s also narrated in the third-person and comprises points of view from the entire Austin family. And I don’t remember if I ever picked this book up when I was a child, but I can understand why the Austin series as a whole confused me. Each book is a very different creature, this one set in a gritty and crime-ridden New York City where gang violence and corruption are endemic, where the Austin family has recently relocated to while Dr. Austin, a country doctor, takes up the opportunity to study surgical lasers at a prestigious research lab.

A surprising detail I learned while reading posts and other articles on this book (this one in particular!) was that not only did L’Engle write her books in set two different systems of time (chronos and kairos), but some of the series themselves were written out of sequence. So that The Arm of the Starfish (which I’ve never read) about Meg Murry’s daughter Polly was published in 1965, before either of the two books that immediately followed A Wrinkle In Time sequentially—which surely posed narrative challenges for their author. As I’ve been reading the Austin books I’ve also found it really illuminating to consider each novel in its own historical context—The Moon By Night (1963) informed by the Cuban Missile Crisis and fears of a nuclear holocaust, and now The Young Unicorns, which was published in 1968 and certainly informed by race riots and social unrest of the late-1960s, which is directly referenced in the text—although in her author’s note, L’Engle explains that her story takes place “not in the present but in that time in the future when many changes only projected today may have become actualities.”

Which is significant, because of how timely so many of historical concerns of The Young Unicorns seem for a reader in 2019, just as the previous book’s did. (When I was young, I thought it would be cool to live through the 1960s. Having now lived through the 1960s redux, I’ve changed my mind.) This novel is asking questions about responding to social unrest, about who to trust, whether we can trust anyone, or if trust itself is a fool’s game. It’s also an exploration of the nature of freedom, in particular to how it pertains to religion. Is obedience freedom? Is disobeying freedom, and when isn’t it? What does it mean to have peace if freedom is undermined to achieve it? (And this is where the title comes in, in reference to a quotation about unicorns that cannot be caught by the hunter but instead “can only be tamed of his own free will.”)

One could say the following of all of L’Engle’s books, but it’s especially relevant here: It’s so weird. Country Doctor Austin has been transformed into a scientist (basically Meg Murry’s dad), and Rob Austin is Charles-Wallace reborn, innocent and purely good, and they even have a reliable hound with uncanny awareness of the presence of evil. The Austins have rented the upper floors of an old mansion on Riverside Drive whose lower levels belong to a scholar and his musical prodigy daughter, Emily, who has been blind since a mysterious attack a few years before. Emily takes piano lessons from the eccentric Dr. Theo, and is helped in her studies and all around by Josiah “Dave” Davidson, a former gang member who was even more formerly than that a chorister at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, which looms large in this novel, its catacombs leading through tunnels to abandoned subway stations and there is even a genie who mysteriously appears when the Austin children rub a lamp in an antique shop.

Dave is Black, and we meet him in the novel’s first sentence, and it’s significant, I think, that nowhere in the novel is his race explicitly stated, but we’re meant to infer it because he’s an “ex-hood” who lives in a Harlem tenement. (Race is stated a few times elsewhere in the book—the Cathedral’s Dean is Puerto Rican, and also an “ex-hood;” also, the two scientists who performed Dr. Austin’s job before him are Chinese and Indian, and a character makes a racist statement about their Asian-ness, at one point, but this character is also literally an arch-villain, so this might be the point.)

That race is otherwise absent from the novel is significant though, especially based on its 1968 publication year and its references to riots, mobs run amok. But this was also the heart of the Civil Rights Movement, and to remove race from the story of rioting and social unrest in northern American cities in 1968 is disingenuous. There is a suggestion too that the rioting and violence is thoughtless and rootless, violence for the sake of violence. But maybe this is what happens when you’re the type of person who doesn’t see colour or write colour, and the definition of progressivism in 1968 for many is that the Austin family regularly had a Black boy sit with them at their table, never mind that his Blackness is never delineated.

While a compelling and gripping read, I also found the novel a bit difficult and disorienting. Part of that is the nature of a book that is all about puzzles, tricks, and mystery, but I’m not sure that was it entirely. There is a dinner party scene where Dr. Austin is discussing his work with the Micro-Ray laser with the visiting Canon Tallis, and then the children leave the table, conversation shifts, and then two pages later, Canon Tallis asks, “Just what is your work, Doctor?” And Dr. Austin replies, “I design and make a small surgical instrument known as the Micro-Ray.” “This is on the principle of the laser?” Canon Tallis asks, and I want to yell at him, “Weren’t you even listening when you were talking about this two pages ago????”

So was it a mistake? But then strange to find a mistake in a brand new edition of the book first published fifty years ago, no? Elsewhere, there is also a reference to the revolutionary work of Dr. Calvin O’Keefe on starfish regeneration, which wonderfully blurs the lines between L’Engle’s series, but then in the previous Austin book, set just six months before, Vicky Austin had referenced A Wrinkle in Time as a literary work as she wishes her family could “tesser” across America just like Meg and Charles Wallace Murry. An inconsistency too or something more interesting than that, and I do love the idea that the Austin’s realism is not quite what it seems.

Calvin O’Keefe’s starfish work is from 1965’s The Arm of the Starfish (ostensibly the sixth book after Wrinkle…), which this reviewer found similar to The Young Unicorns but more problematic and less compelling. And in her review she also lays out the problem of Meg Murry, fierce and brave heroine of A Wrinkle In Time, but one who is forever playing second fiddle to a brilliant male character, whether it be her husband or her brother. I have always loved A Swiftly Tilting Planet, the third book in the series, and I’d always hoped that the reason Meg Murry O’Keefe is sitting in her parents’ kitchen while her husband is out saving the world from nuclear annihilation is because she’s nine-months-pregnant with their first child. But if Starfish is any indication, Meg Murry retired from being a feminist icon as soon as she comes of age: “Always called Mrs. O’Keefe, she is calm, reassuring, intent, focused on mothering her children, a near clone of Mrs. Austin in the Austin books, serene and capable. And all wrong for Meg Murry.”

As with the line, “Daddy doesn’t like women who wear pants,” in The Moon By Night, Mrs. Austin in The Young Unicorns is happy enough to uphold the patriarchal status quo. As her daughter Suzy explains of how Mrs. Austin gave up a fledging music career to become a doctor’s wife, “Well, she’s just Mother. She decided she didn’t want to be something, didn’t she?” And it’s interesting that we see L’Engle seemingly unable to write a woman character who balances her creative passions (whether they be art or science) with marriage and family life, especially since she herself managed to do so. Although one could speculate how successful L’Engle actually felt she was in this balancing seeing as she wrote these idealized self-denying maternal figures over and over again.

“I think the closest we ever come in this naughty world to realizing unity in diversity is around a family table,” Canon Tallis comments after spending time with the Austin family, and questions of family, connection ,and disconnection recur throughout the text. For the first time, the Austin family themselves feel estranged from each other, and there are also questions of how they can possibly imagine themselves as an island of peace and calm in a world so dangerous and broken. In their own small town, it was easier to suppose it, but living in the city it becomes undeniable that all things are connected. “And it’s all about what Grandfather’s always saying, how we can’t love each other if we separate ourselves from anybody, anybody at all, and how anything that happens to anybody in the world really happens to everybody.”

February 18, 2019

Lemon, it’s Wednesday

“Lemon, it’s Wednesday,” so goes the 30 Rock meme after Liz Lemon comment on the week that’s been, which is the way I was feeling last week about the month of February, when we weren’t even two weeks into it yet. We’ve had stomach bugs, and kid emotional turmoil, disturbed sleep, terrible weather, and so much snow shovelling. We have a provincial government whose sheer incompetence is the only thing between it and the destruction of our public institutions, and so last week I was out at two community meetings with galvanizing plans and discussion for how we can stand up for public education. I am not exaggerating when I tell you that most of my neighbourhood is covered in a thick and impermeable sheet of ice, which means that any walk down the street is a hobble, and I’ve got leaks in my boots. I’m feeling discouraged and sad about how my writing career is panning out, with a novel rejected in November and the one I did publish prominently featured in the chain bookstore clearance bin. And I’ve reached that inevitable point in my own plans for exciting things this year where I wonder if I’m fooling myself and everybody thinks I’m a total idiot. I was so tired last Thursday after running around taking everyone to their swimming lessons, and also having dinner ready early so that everyone could eat around their swimming lessons. “I’m sorry I was cranky,” was the text I sent home while Iris was practicing her flutter kick in the pool before me. “I think what I need is to just come home tonight and take a bath.” But of course there would be no bath, because before the night was out it would become clear that I have head-lice. Head-lice was the one thing my February had been missing.

My brain is still teeming. The itch. It doesn’t require proof or evidence. Thought is enough. You do it yourself. Lice. Imagine them crawling on your head. Claws touching skin. They pass over us, across this family. —Alexander MacLeod, “Wonder About Parents”

In the last few days, we’ve spent over a hundred dollars on expensive shampoo and a lice comb, and my husband has spent hours picking over my scalp with attention to detail. And it makes me wonder what the women who end up with lice who don’t have partners do? Let alone the women who have lice who don’t have a spare $80 lying around to buy the shampoo necessary to treat the whole family (and for best results, repeat the process in seven days). I feel outclassed by the people who are able to call in the lice-trepreneurs (this is a thing!), but at least I can afford Nixx. And it makes me think about the “Bug Economics” essay in Carissa Halton’s wonderful book, Little Yellow House, which I read in January. She writes about how many families are unable to afford the “kill-these-damn-bugs shampoo,” which might not even work anyway. She goes on to write about another inner-city scourge, bed-bugs, but the principle applies to lice as well: “While everyone can get [them], the poor are most likely to have to deal with the creatures longer than most.” I am lucky: I am not poor. Also, I don’t have bed-bugs. (Yet? February has a lot of steam left in it still.)

Lice. The third week. Head checks in the morning and head checks at night after the baths. You need to go slowly. A separate bath for every person. New water. Fresh pillow cases every night. New sheets. New blankets. The washing machine is going to die. Hats and T-shirts and hooded sweatshirts. Brushes and combs and hair elastics. Water boiling in the kettle. Everything that touches us needs to be scalded. —”Wonder About Parents”

Lice is a metaphor. Lice is also not a metaphor, which is the unfortunate part of this story, or at least one unfortunate part. (It is February. There is very little fortune.) But still, lice is a metaphor for the secret shame that creeps around your head, and makes you unfit for others’ company. It marks you and makes you less than, and everybody tells you that they’re attracted to people with clean hair, but nobody believes that anyway. You start contemplating pixie cuts, crew cuts, buzz cuts. The chance to be somebody different. Because what if I’m completely hopeless, and I’m just the last person to realize it? It’s taken me almost forty years to contact lice, and I’d always kind of thought that I was immune to it all, just like how I thought I was immune to failure. Or dared to hope my story would end up different than most people’s, is what I mean, that it could even be a story of triumph. Everyone gets lice sometimes (although usually it’s when they’re six and not thirty-nine), and everyone’s book ends up in the clearance bin, but still, who wants to be everyone? Necessary humility, certainty, but insufficient consolation.

The only way out is through.

Which is true for head-lice, and Februaries, and any period of unhappiness. It’s never easy, because you get to March and you’re still carrying February inside you, and maybe you’ve still got nits (although I’m really hoping I don’t). And to be honest, I don’t any advice that is better than that, to just keep going, in addition to washing one’s hair with vinegar, which might not even help, but I like that there is something else I can do—in addition to the chemical shampoo.

February 13, 2019

Mini Reviews: Three Books on Family

The Last Romantics, by Tara Conklin: The summary on the jacket flap of Tara Conklin’s new novel The Last Romantics tells you that this is a story that begins in a yellow house, with a funeral, an iron poker…”a free and feral summer in a middle-class Connecticut town.” And while all this is true, it doesn’t begin to tell the reader what this book is about, a book that takes place over a century and actually begins in an auditorium in a dystopian future, a world wracked by climate chaos, where 102-year-old Fiona Skinner is asked to explain the story behind her most famous poem. And I’m amused by the challenge this novel must have created for marketers, who prefer novels to ones that can summed up in a sentence, and this one definitely isn’t one of those. A clue to what’s actually going on here lies in a blurb on the back by Meg Wolitzer, whose two most recent books have been similarly ambitious in their reach, not explicitly about anything either except the story itself, about the characters within and how time changes and complicates their connections. The story is the sweep, and so it is here, although it’s not always completely convincing as it is in Wolitzer’s more masterful work (though I will admit this is a high bar).

There are narrative strands in this novel that don’t go anywhere, and while one could argue that life itself is a bit like that, the reader gets the impression that this novel was once a more larger and more unruly manuscript and much got cut in the taming, and now there are several parts of the novel that don’t know what to do with themselves. There are also a few plot points that hinge on characters doing unfathomable things, which was annoying. But, most fundamentally: this novel was never not interesting, and I found it thoroughly engaging. The shifts between point of view (no small feat with a first-person narrator) was beautiful crafted, and provide moments of real illumination. The Last Romantics is a curious beast, and I can think of worse things for a novel to be.

*

Reproduction, by Ian Williams: This debut novel by award-winning poet Williams is another curious beast, but more deliberately so than with Conklin’s book. Williams brings a poet’s attention to form, always pushing at the novel’s limits, making it hold more, do more, be more—and it mostly absolutely works. Beyond form, this is always a family story like none I’ve ever read before—two people meet in a Toronto hospital room in the late 1970s and their mothers are dying. One is Felicia, a teenage girl from an unnamed Caribbean island, and the other is Edgar, adult son of a wealthy German immigrant family. One thing leads to another, and after a time they end up having a child together, though Edgar leaves the scene, and Felicia ends up raising her son, Armistice, in the basement apartment of a suburban Brampton side-split where Oliver lives, and we find them all next in the 1990s and Oliver’s two children have arrived for the summer from their home with his ex-wife, and one thing leads to another, and another child is born. Which all sounds more straightforward than it really is, because there are tricks with language, details, timelines and lineage. I loved the specificity of the story, it’s strangeness, but its utter plausibility, how it’s not a sensible story, but it makes perfect sense. This is another book that is never not interesting, but it’s also a demanding read—so when I finished Reproduction, I made a point of picking up a novel that was in a different gear. And this is my favourite thing about books, that there’s not just a single kind…

*

Her One Mistake, by Heidi Perks: The opposite of a book that’s unlike any I’ve ever read before is Her One Mistake. a psychological thriller with an unreliable narrator Gone Girlish vibeWhich certainly has been overdone in recent years, and has its pale imitators, but I thought Heidi Perks’ novel was really terrific—and reminiscent of the TV series Broadchurch, and not just because of the setting in Dorset, UK. This one starts when Charlotte agrees to take her friend Harriet’s young daughter, Alice, to a school fair, but then Alice goes missing, and Charlotte’s negligence is seemingly to blame. But as always, the real story is more complicated, and there are twists and turns to find out what really happened to Alice. My only criticism would be that Harriet’s husband is way too absolutely evil to be a realistic human character, but then a) if I’ve learned anything in recent years it’s that some men’s capacity for abusiveness is beyond my wildest imaginings and b) none of the novel’s twists hang on the possibility of his character being anything than what he is, so there’s nothing cheap happening here. I really loved this book, and its ending was gripping and explosive and had me shouting at the page.

February 12, 2019

Gleanings

- By-gone letters pull us intimately into the moment of their writing and thus seem truer than memories.

- I like to believe that leaning is love.

- Literature strengthens our imagination. If we all have the tools to try to imagine a better world, we’re already halfway there.

- I like the smell of coffee percolating, the way tulips nod their heads when brought inside, handwritten notes and letters, walking barefoot in the sand…

- As a writer, what I’ve done is not as important as what I’m going to be doing.

- And I noticed it because I was looking.

- This morning I went out to see if the small dark animal that jumped into the bush beyond my study window left tracks in the snow.

- Who needs a canvas when you’ve got walls!

- Undoing crochet still leaves you with all the yarn, after all: you just have to make something else out of it.

- It’s a stance, bewilderment. It’s a way of entering the day, and of thinking differently, even in times that seem to call for its opposite.

- I recognize that this sadness is the cost of loving my daughter and I wouldn’t change that for anything.

- But it is not true that identity politics are necessarily divisive. Difference is a fact of life, to which divisiveness is only one response. Inclusiveness is another: not just tolerating but celebrating difference, fighting for the rights of all, not just the few.

- My Year of Slow.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

February 11, 2019

On Asking for Things

I think I’ve been audacious precisely twice in my life, and I’ve written about one of those times before: the time I encountered hydro workers on a country road and pulled over to ask if I could have a ride in their bucket. “I can’t think of a reason why not,” was the worker’s incredible reply, and so we had an adventure, just because we’d had the nerve to ask for it. But such nerve, for me, was uncharacteristic, and while I will forever wish I was the kind of person who was ever asking for bucket rides, that day was an anomaly. Instead, I’m pretty religious about following the rules, keeping to the speed limit, staying in my lane, and watching spacing.

(“If we give one out to you, we’ll have to start giving them out to everybody,” I once told a patron when I worked in a library, and he’d asked to borrow a pencil. Libraries, with their decimals and rules, are my natural habitat, and the habits I acquired there have proven awfully hard to break. At my local branch, I still get rankled when I see children eating crackers by the board books, scattering crumbs across the floor.)

The other time I was audacious was completely by accident, or ignorance. When I was seventeen, I spent a week in Edinburgh, where my aunt, uncle and cousins were living for a year, by which I meant that my youthful naivety (and stupidity) was unleashed on the international community. I was a ridiculous human being, and insisted on wearing pyjamas on the plane, WHICH WAS NOT GLAMOUROUS. I also thought the whole point of travel was to try out the McDonalds menu in other cities. In Edinburgh, the commercial streets were lined with signs that said, “To Let,” and every time I saw one, I pointed and shouted, “Toilet!” I had to purchase a second suitcase in a charity shop in order to bring home the supply of chocolate bars I’d bought on my trip. And even with all this, my cousin consented to spend time with me. She is a very understanding person, and to this day (mysteriously, on her end) one of my dearest friends.

We spent a week together, aimless and kind of dumb, eating McDonalds, and visiting castles, and TopShop, and then one day we walked past a hair salon and there was a sign in the window: OAP Haircuts, £3. Which I thought seemed like a very reasonably price for a haircut, so I went in and asked for it. “I would like an OAP haircut, please.” I recall how the staff responded kind of strangely, but I just wrote that off as being because they didn’t much chance at this salon to cut the hair of a nubile young lass with long chestnut hair—everyone else in the place was kind of old, see? And afterwards, all this was just a funny story I told, about the time I went to Scotland and got my hair cut (which is far more characteristic than the bucket ride, if I’m being honest). We even took a photo to remember it by.

It was not until years later that I figured it all out, what an OAP haircut actually was, why everyone else in the salon had come in for a set. That an OAP is an “old age pensioner” (surely this had come up in Adrian Mole. How had I missed it) and what must the woman at the desk had thought when I walked into the place asking for a senior’s discount? (On the other hand, I was foreign. Being foreign helps you get away with so many things. Which makes me realize that “I think I’ve been audacious precisely twice in my life” is not exactly accurate, because doing the year we lived in Japan, we did audacious things all the time. As gaijin, no less was expected of us.)

My biggest takeaway from all of this is that sometimes, if you want a thing, all you’ve got to do is ask for it. Sometimes, due to sheer audacity—accidental or otherwise—the person you’re asking will have no choice, but to just give it to you. (Unless it is a pencil, and I am working at the library circulation desk. Because if I gave one to you, I’d have to give one to everybody.) That being naive and ignorant enough ask for a thing can sometimes actually be the key to getting it. And that’s not the whole story, of course, and anyone who tells you that your consciousness is the key to unlocking the universe IS LYING. But still, there is power in asking. Sometimes it’s as simple as that.