March 13, 2019

A Ring of Endless Light, by Madeleine L’Engle

“Why all of this, my Lord and my God? Either bring the world to an end or remedy these evils! No heart can support this any longer.” Vicky Austin is reading to her beloved Grandfather, who is dying of leukaemia, and is startled when he bursts out with this utterance. And he explains, “Teresa of Avila said that, in the sixteenth century. It should comfort me that there have always been outrages to the Divine Majesty. But it doesn’t.” He points to the headline in a nearby newspaper: “The headline was a plane crash, a big one, with everybody killed.” What is particularly outrageous about the story is that after the people were killed, others had ransacked the wreckage and the bodies for money and valuables—but this is not my point here. Instead I want to talk about the uncanny way that Madeleine L’Engle’s Austin books have been speaking to the moment I’ve been reading them, even decades after they were written.

Because a big plane crash that killed everybody on board was also top of the news yesterday, 18 Canadians among those who perished on the Ethiopian Airlines flight that crashed on Sunday. And Vicky Austin talks to her grandfather about how she’s been avoiding the news that summer—it’s been a heady time with her grandfather’s illness and the death of a family friend. And Vicky considers, “But not reading the paper only kept me from not knowing things; it didn’t keep them from happening.”

Grandfather, anticipating Twitter in 1980 (when the book was published), says to Vicky, “Maybe instant information isn’t good for us. We can’t absorb it.” Oh, Grandfather. You have no idea.

These books relationship to time continues to fascinate me, seemingly linear and more straightforward than the Wrinkle In Time series. And yet there is more going on than is immediately apparent—first of all, Vicky Austin’s father and another character in this book have all been involved with the research of Dr. Calvin O’Keefe, who is Meg’s companion (and eventually husband) in the Wrinkle series. Which is to say that they inhabit the same universe. But time also unfolds at a different pace than the Wrinkle books do. This book is also written more than a decade after The Young Unicorns, and yet set just a handful of months later. And finally, there is the incredible sense I have that I’m meant to be reading this books right here in 2019, and the reading experiences I’m having are so visceral. I made a chicken dish the other night that was the same dinner I made when I was reading The Young Unicorns, and I was full of Young Unicorns nostalgia. I’d only read it two weeks before, but still. I’ve found all these books so utterly absorbing.

This one is set the summer following the big road trip in The Moon By Night, after the year in New York that was depicted in Unicorns. The Austins have returned to Grandfather’s island to be with him at the end of his life, but focus is shifted when the family’s good friend dies of a heart attack during a sea rescue. The sea rescue turns out to be for Zachary Gray, who was attempting suicide after the death of his mother (who was cryogenically frozen!). And yes, Zach’s back, and as obnoxious as ever, but Vicky is a year older and able to call out his bullshit in a way she wasn’t strong enough to do before. Meanwhile, she’s found out that she has dolphin ESP and is participating in experiments with Adam Eddington at the marine biology station—not that he ever offers to compensate her for her labour, of course, though the station is a pretty bare bones operation.

Which brings me to gender and the Austins, which has shifted a bit since 1968 when the previous novel was published. I’m not saying that Mother wears pants now (because as we learned in The Moon By Night, Daddy doesn’t like women in pants). But none of her children call her “nothing” in this book for her absence of a profession, and she even contemplates doing something with her life when the time comes that the children are grown and gone. She also mentions “inverse sexism” twice, which is kind of terrible. Advising her daughter Suzy that it would only be “inverse sexism” that cheated her out of her understanding her deserved place in the definition of “mankind,” and also calling it when it’s implied that her choice to leave her musical career for marriage was somehow unprogressive. But that sexism is mentioned at all is a kind of progress, I suppose. Vicky is also much less passive in her relations with the young men who are courting her (three of them!). It’s really clear though in reading these books that Madeleine L’Engle was a decidedly unfeminist writer, never mind Meg Murry’s fierce intelligence and strength of will (and remember that Meg in subsequent books becomes just “Mrs. O’Keefe,” wife of the brilliant biologist).

(It is worth noting that Suzy Austin remains unconvinced about her mother’s explanation for “mankind.” I like that L’Engle leaves the space, the possibility, the question there.)

I would like to know more about L’Engle in relation to feminism, and I wondered if she considered it a dogma worth resisting. All the books in the series so far have been about resisting dogma in the context of religion, even as the books themselves are so religious and concerned with issues of morality and mortality. The underlying message in each book seems to be about the danger of thinking we understand everything, about God and the universe in particular. (A thing Meg Murry’s mother once told her is, “But you see, Meg, just because we don’t understand doesn’t mean the explanation doesn’t exist.”) Vicky recalls her grandfather telling her, “As St. Augustine says: If you think you understand it, it isn’t God.” Not knowing seems to be fundamental to understanding, which to a religious person is the definition of faith, but this idea is applicable for those of us who don’t have a religion too (or those of us who are trying to figure out feminism). Just as darkness goes with light, life with death, all of it bound together, this miraculous world and universe.

March 12, 2019

Gleanings

- Why can’t we have parent-friendly Parliaments?

- My mother, you see, was an avid recycler from way back.

- David Tennant does a podcast with…

- “Darling, I love you goddamn, goddamn, goddamn much.”

- I feel like cancer has made me give up enough in this life.

- “Just a humble, decent dude”

- Someone called this blur an ordinary loneliness.

- But more so I’m here to iron things out. There is a decision I need to make and neither choice is ideal or easy.

- Here’s another definition of irony: It’s when the woman who writes the story of her life feels she has to prove that the story is hers.

- It’s not hard to understand why some people take such issue with us being able exercise the most complex and significant power there is.

- I am so grateful for this conversation and the chance to stumble through these thoughts and try to get closer to what I think and figure it out. I don’t know about this idea that we’re all supposed to know everything all the time…

- Stop telling women they need to be different or learn different things and start building an organization where they are themselves.

- Something that I think I cannot examine and re-examine and remember often enough.

- The woman I am today is an amalgam of a great many snapshots…

- I’ve only discovered the Moomins as an adult…

- I logged it all here like a dutiful aughts-era blogger with no larger agenda for what it would become, because how could I have known?

- Does the place where one was a child imprint more deeply than anywhere?

- It’s always a little adventure, to delve into a handbag I haven’t used in months, years.

- She is seeking not so much escape as neutrality: reading is a form of withdrawal, a way of refusing or rejecting the whole otherwise intractable situation around her.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

March 11, 2019

Why I’m waiting for your next blog post

(I sent the following message to writers signed up for Blog School: Pickle Me This mailing list last week, but I think you deserve to read it too. And if you want to sign up for Blog School updates, you can do so here AND receive a copy of my free download, “5 Prompts to Bring Back Your Blogging Spark.”)

For many bloggers, the biggest impediment to actually getting to PUBLISH is the idea that maybe no one’s reading, so what even is the point? And my smart answer to this has always been that you should be blogging like no one is reading anyway—so if no one actually is reading, doesn’t that just mean you’re doing it right?

My non-glib take on this is different, however, because I’ve never been more hungry for good things to read online, in blog posts in particular. It’s why I’ve started “Gleanings”, a weekly series (also available as a newsletter) where I collect links to all the fascinating pieces I’ve come across on the internet—articles, essays and blog posts that made me think and/or delighted me. I’m so grateful to writers who continue to craft smart posts, make thoughtful arguments, and introduce us to excellent people, places and things, all of this countering the toxic discourse we so often encounter online that’s lately rearing its ugly head in the real world. I continue to believe—because I’ve seen the evidence—that with our own small corners of the internet, we really can make the world a better place.

And because I know that crafting meaningful blog posts is important to you—you were curious enough to download my “5 Prompts to Bring Back Your Blogging Spark” after all—I wanted to check in and encourage you to keep going. If you haven’t updated your blog in awhile, now is the time to do it. If you’ve written something lately that you’re proud of, I hope you’ll leave a link below in the comments so I can read it, and so my readers can read it too—because I’m not the only one who’s craving great posts to read.

So many of us are looking for goodness these days, but blogs are an opportunity to get proactive and actually make some. I’m really not kidding when I tell you that I’m waiting for your next blog post, and I promise I’m not the only one.

March 8, 2019

The Secret Life of Alice Freeman…

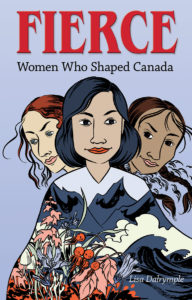

Today at 49thShelf, we’re featuring an excerpt from new book Fierce: Five Women Who Shaped Canada, by Lisa Dalrymple and illustrated by Willow Dawson, which is a book I’ve been reading aloud to my family over the last two weeks, and one we’re all enjoying. In particular the story of Alice Freeman, Toronto schoolteacher in the 1880s who led a secret double-life as an investigative reporter. It’s so good, and you can read it here.

March 7, 2019

Why Your Own Small Corner of the Internet is Going to Make the World a Better Place

I spent last week gathering signatures for a petition among parents at my children’s school calling on our government not to increase class sizes—which is a call that everyone was happy to get on board with. It was the “duh” of petitions, but even still. “You’re awfully optimistic,” one person remarked as he signed it, but I’m really not. I understand that a majority government with short-sight and an ideological agenda is probably not going to be moved by a bunch of signatures in a riding that didn’t even vote for them not to make cuts to our already under-invested education system. But this still doesn’t seem to me like a good enough reason to sit back and just let it happen, to do nothing. Even if the outcome is the same, the outcome won’t be the same, because there will have been resistance. The fight always matters, even in the rounds you don’t win.

It was probably twenty years ago when I had a revelation about my ambition to become a writer, which was that even if I never succeeded in my goals, merely striving for them would end up taking me on a different and further trajectory than if I hadn’t bothered. And maybe what I’m trying to say here is that I’m comfortable with the notion of futility, or perhaps that there is no such thing. I believe in small things, and how they lead to possibilities, and I’m going to keep on tending my own garden, because it’s a thing that I can do.

Although by tending my own garden, I don’t mean retreating from the world, planting a row of tulips behind a barbed wire fence while the world falls apart outside. I don’t mean walls, because walls aren’t real. If someone’s not okay, then no one is okay, because there is indeed such a thing as society. And there has never been a more important time to be connected with society, with community—which is why I spent last week gathering signatures for a petition (on paper, with pencils, and everything). Sometimes social media can give us the illusion that we’re being political, making a difference, but I’m starting to think that it doesn’t count. I’ve been making an effort this year to replace to my Twitter engagement with real things—blog posts instead of tweet threads, sharing links to things I love in a newsletter, walking around the school yard and talking to people in my community instead of writing obscenity-laden tweets to idiot politicians who are never going to read them which is really only an exercise in screaming at the sky.

What I mean is that I continue to insist that my voice matters, however in a small way, and so do the choices I make and the causes I show up for, the principles I instil in my children, and my decision to live with integrity and stay true to the things I believe in even as integrity and truth don’t seem so fashionable these days.

And lately I’ve been tending my own garden especially by going back to the blog, planting thoughts and ideas and watching them grow, and even watching them spread as other people read and respond and write posts of their own. I continue to insist that blogs matter too, and that the internet needs blogs more than it ever did—a place where there is thoughts instead of noise, where the people aren’t bots, where there is room to expand and explain and even change your mind. Blogs are important in 2019 because they aren’t underlined by corporate interests, because what parts of them we read aren’t determined by algorithms, because of their focus on language at a moment when politicians are making meaninglessness into an art form, because of their obscurity even and how they give us the freedom to explore off our own beaten track, because they’re not part of an industry that’s flailing, dying, desperate. There’s nothing desperate about a blog.

To blog is to be hopeful—that words matter, that someone is reading, that small things make a difference.

“You’re awfully optimistic,” one might suggest in response to this post, but again, I’m really not. I just believe that doing what little you can is always better than doing nothing. I don’t think that people understand enough about their own power—drop off a loaf of a banana bread at your neighbour’s, or shovel their driveway, and you’ve transformed your community into a place where such things can happen. How we spend our days becomes how we spend our lives, and who and what we are (online and off) becomes the world.

March 6, 2019

Autopsy of a Boring Wife and The Matchmaker’s List

It’s been over two years since Marissa Stapley and I sat down to talk about the state of Canadian commercial fiction, and while I’m not sure the genre has yet received the respect that is its due, I’m glad to see there have been changes on some fronts. When I asked Stapley what could be done to promote diversity in commercial fiction and challenge its glaring whiteness, she dared to be optimistic, saying, “There’s room for all the stories. The tent is getting bigger and bigger. It’s exciting.” And here in 2019 there is demonstrable evidence that this is true, not least of all commercial and critical success by writers such as S.K. Ali (who writes YA) and Uzma Jalaluddin, whose Ayesha at Last had its film rights scooped up last year. Finally, commercial fiction lovers are getting the chance to read great books from a diverse range of perspectives—including two titles I’ve loved lately.

Autopsy of a Boring Wife, translated from French by Arielle Aaronson, is by award-winning Quebec writer Marie-Renee Lavoie, the story of a woman whose husband has left her for another (younger) woman, because she’s boring, Diane supposes. Because she can’t even dance: “I was born boring. The gene in question slipped into the double helix of my DNA during conception.” But Diane, of course, is anything but boring, and the narrative follows her through the painful aftermath of her husband’s confession, their separation, and her attempts to reorient herself in this brand new life, which she takes on with aplomb via a sledgehammer to severals walls in her home and antique furniture. She follows her best friend Claudine’s mad schemes to get on the rebound, makes confessions to her therapist, attempts to make a move on a coworker and ends up with losing her boots (this is not a euphemism), gets delicious revenge on her husband’s girlfriend, hides in the pantry while the realtor shows her house, and does her best not to take it all out of her children. And Diane’s incredible love for her adult children is what grounds her, and what grounds this novel that’s full of quirks and zaniness, as Diane talks about how parenthood is a combination of visceral fear and a kind of gratitude.

The novel is written in the first person, mostly dialogue and little exposition, and the reader has to read between the lines to get a real understanding of the extent of Diane’s pain and suffering, sledgehammer aside. (She’s pretty blasé about the sledgehammer. Her neighbours are certainly concerned.) Autopsy of a Boring Wife is slapstick, funny and absurd, but underlined with a tenderness and poignance that will have you rooting for happily ever after after that.

Happily ever after is also the object of Sonya Lalli’s first novel, The Matchmaker’s List, although Raina and her grandmother have different ideas about what that entails. She’s just about to turn 30, which is the age she’d promised Nani (years ago, when 30 seemed an eternity away) that she’d be married, and though she’s still pining for a man who broke her heart and more devoted to her job in downtown Toronto as an investment banker than to finding a new relationship, she agrees to go on dates with a list of eligible men that Nani has selected for her. Which sounds like set-up enough for mix-ups and mishaps, because some of the men are ridiculous, and Raina never holds back on letting them know what she thinks of them, but Lalli throws another wrench in the works when Raina’s Nani incorrectly infers that Raina is gay, which rocks their Hindu-Canadian community and creates even more trouble for Raina. It’s possible the novel is a bit too packed—Raina’s old boyfriend shows up in town; her best friend is getting married and Raina has feelings for a groomsman; Raina’s wayward mother (who had Raina as a teenager, which makes Nani all the more determined to marry her granddaughter off properly) drifts in and out of Raina’s life; and a family friend who actually is gay struggles with whether or not to let his parents in on his secret. But Lalli’s writing is smart and funny, and her characters are refreshingly flawed and multi-faceted, which made reading this novel about family and friendship absolutely a delight.

March 4, 2019

Gleanings

- I read like a buzz saw cuts wood.

- But I think I’m often my best self in hotels.

- I’m at the point in my years when, looking back, I can see that my life has been an accumulation.

- There is maybe no better time, then, to invest some effort in happiness, in making good for ourselves and others.

- Despite my reproductive difficulties, I’d forgotten that the simplest things are often the hardest to make.

- “There is a sense of the established power being threatened by women gaining respect,” she said.

- And those words became a sentence and the sentence became a paragraph…

- “The idea of male experience being representative of general experience, and female experience being women’s experience only,” she says, “is depressing.”

- It is simply one of the saddest songs about unrequited love I’ve ever heard, and I think about it almost constantly..

- Because the word character has two relevant and related meanings.

- How do we turn the situation around so that people are more willing to share some of the abundance they may have generated?

- If there are more like Russian Doll on the horizon, this might not be the darkest timeline after all.

- You might already do this, but I’ve found subscribing to newsletters is also a bit of an antidote to the whole potential glargishness of the internet.

- What Happens When a Book’s Character Comes to Life.

- That’s the thing about wrinkles, on someone else’s face they’re endearing, quirky –– life’s map lines.

- Winter is long in this climate/ and spring—a matter of a few days

- How effectively a piece is able to instantly make me feel something is a good gauge of its worth.

- Toronto Letter Writers Society

- So I took pics of dogs who weren’t so fussy about their privacy–and you know what? Dogs show you a lot about the world they live in.

- And since winter isn’t over just yet, hot chocolate and homemade sugared marshmallows are the way to go here.

- But compared to my early mommy writings on this blog the old adage “things will get easier” is so true.

- …may I remind myself that I used to be the banana queen of the Don Valley Parkway.

- And the only primroses are in memory, the drifts of them in the hedgerows near the island where I lived for a time in Ireland and used to pass on my way to the nearest town for groceries.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

March 1, 2019

Climbing Shadows, by Shannon Bramer and Cindy Derby

I want to sing the praises of the kindergarten lunchtime supervisors, because it’s not often enough that people do. A job that is underpaid, under-appreciated, incompatible with most schedules, and without whom the school day could not proceed. When my eldest child was in kindergarten, her lunchtime supervisor was called Miss Vivian, and—I’m not sure if this is part is even true—all the children believed her to be a retired police officer from Jamaica. You didn’t mess with Miss Vivian, but then some people tried to, and one day my daughter told a story of a notorious boy in her class who’d pulled his pants down, which made me decide to send Miss Vivian a thank-you note for the work she did, plus a gift card for the liquor store.

Not everyone gets an LCBO gift card for being a kindergarten lunchtime supervisor, however. Poet and playwright Shannon Bramer got a collection of poetry instead, a poem for every child in the class that she’d worked with about anything they wanted. “Being a lunchtime supervisor in a kindergarten room involves container opening, orange peeling, snowsuit detangling, and mitten hunting,” she writes in her beautiful Author’s Note, and she also made it about poetry too. She shared the work of her favourite poets with the class, brought in illustrated collections to show them. “My kindies learned that poetry could make them feel and see and remember things. A poem could tell a sad story or it could make them laugh; it could make them think. A poem could be hard to understand beautiful to listen to at the same time.”

Lunch poems are not a new thing, but Bramer’s Climbing Shadows is my favourite twist on the concept yet, a collection that involved out of her collaboration with the children in the class, and which is published now by Groundwood Books with dreamy, appealing whimsical illustrations by Cindy Derby. Poems that remind me of children’s voices, their questions and preoccupations, but which also aren’t pandering and play and delight in language with the deftness of poetry intended for readers of any age. With enough familiarity to draw the reader in, but spaces between the words and lines enough to invite questions and wondering. Poems about octopuses, birthday parties, polka-dots.

“My mom is pushing the stroller/ through slush and broken ice/ and there’s lots of cold water shining/ on the street”

February 28, 2019

The Homecoming, by Andrew Pyper

What I’ve always loved best about Andrew Pyper’s novels isn’t necessarily their plots, the super suspense, or the scary scenes that have literally kept me up at night. Although all these things are what make his books compelling, of course, and why I’ve been a fan of his work ever since I read The Killing Circle more than ten years ago. But for me the biggest attraction of an Andrew Pyper novel are the human connections, the relationships that make the stakes of the suspense plot so much higher—the father/son relationship in The Killing Circle, the brother and sister in The Damned, and another set of siblings in his latest book, The Homecoming.

Which is a weird book, and it’s obvious from the novel’s opening that something is a little askew. The Quinlan family isn’t quite normal, even beyond the ways in which they know they’re not normal—their father has just died, a figure who was always distant and often absent, and who has invited all of them together to receive their inheritance whose terms require that they spend 30 days at a remote lodge deep in a forest in the Pacific Northwest. And they agree to it, Aaron, a doctor; his sister Franny, a recovering addict grieving the death of her young child; their mother; and their fourteen year old sister Bridge, the person to whom Aaron is closer than anyone else in the world. They agree to it in hopes that the experience will give them answers to the questions they’ve had for years about the man their father/husband was, because what could be worse than so much not knowing?

Turns out: a lot. Other surprise guests arrive at the lodge, it becomes clear they’re all even more isolated than they thought, the woods are haunted, there’s an abandoned Christian summer camp with Satanic graffiti, and someone’s skulking about with a hatchet. Beyond the confines of the forest is a world that might be described as dystopian were it not for its resemblance to the present day, with militarized power, civil strife, and racial divides, all of which makes the action happening at the lodge seem that much more pressing, dire and claustrophobic.

I have to confess to having read a lot of books lately in which a character realizes that “Everything he knows about his life is wrong!” but this one pretty much takes the cake. Indeed there’s a twist, and it’s a wild one, but not a cheap one, and it works, and not least of all because Pyper has creative a huge emotional investment in the relationship between Aaron and his sister Bridge. Their connection makes the twists matter so much more, and underlines the poignance of the novel’s ending. The Homecoming didn’t frighten me as much as it thrilled me and moved me, which is a pretty remarkable combination. I liked this book a lot.

February 27, 2019

Happy Parents, Happy Kids, by Ann Douglas

Early on in my career in motherhood, friends would recommend Ann Douglas’s parenting books to me on the basis that she wasn’t an ideologue. “She recognizes that there’s not just one way to do things,” I remember people explaining, because she recognized that there was not just one kind of child, or one one of family, or just one simple way to make a baby fall asleep at night. It’s a kind of pragmatism that can be rare in the parental guidance industry, and which has endeared her to a generation of readers looking for advice applicable for the world we live in as opposed to an ideal one. (Douglas’s most recent book before her latest was Parenting Through the Storm, advice for parents whose children are living with mental illness.)

Her new release is Happy Parents, Happy Kids, built on the premise that in order to make positive change in family life and the life of a child, a parent should start with herself, with her own wellbeing. A suggestion that is more important than it has ever been, perhaps, because parenthood itself has never been harder. Fashioned into a verb, made into a competitive sport on display with social media, complicated by differing philosophies and an insistence that the stakes are high for everything. Because what does the future hold? Douglas’s first chapter is called “Parenting in an Age of Anxiety,” and she goes on to illuminate how parents are challenged by questions of work/life balance, why it’s easy to always feel distracted, and how it’s too easy to lose focus on the parts of having children that are wonderful and rewarding.

Her advice on avoiding distracted parenting is really terrific (the only social media I have on my phone is Instagram, but since reading Happy Parents… I have removed the app from my phone’s main screen and turned off notifications, and my life is better for it), and she has similar suggestions, backed up with research, for connecting with your children, with your partner, for figuring out what is important to you and what your priorities are in your family life, for living with stress and hardship, overcoming past trauma, choosing calm over “stressed,” the benefits of being your authentic self as a parent, and how to resist a goal-oriented approach to being a parent: “Parenting is endlessly inefficient—and that’s okay.” Implicit in every part of this book is an understanding that families come in all shapes and sizes, with a wide variety of challenges and every kind of normal. There is a lot to work with here, and not all of it is applicable to my life at the moment, but I can foresee moments where all of it might be. This is the kind of book that would be good to keep close at hand, to dip in and out of, because you know (as the book knows) that the only sure thing have having children is that everything is changing all the time.

While “Be the change you want to see in the world” (or “Be the happy you want to see in your family”) is worthwhile and really practical advice, however, it’s only the beginning of the story, and what I love about Happy Parents, Happy Kids is that Douglas knows that. “Recognize that many of the problems that we are grappling with as parents are too big to solve on our own,” she writes in the book’s first chapter. “Systemic problems require systemic solutions, after all. So look for opportunities to join forces with other people who share your desire to create a world that’s kinder and friendlier to parents and kids.” She couples her individual-based approach to self-improvement with an awareness that society itself also needs to change, and that part of the reason that having children can be so overwhelming is because the system is stacked against us. And it’s only when we join forces and work together that things can begin to change.

The book’s final section is all about the necessity of building a village—we featured an excerpt on 49thShelf last month about the challenges and opportunities of online community. And this chapter sums up what underlines the entire book—that we can only do this all together. (I’ve also been signed up for Douglas’s newsletter, The Villager, for the last few months, with her thoughts and ideas about creating community and finding common group in an ever-shifting world, and I love every instalment.)

She writes, “The issues we’re grasping with are so much bigger than any of us, which makes them all the more challenging to resolve. The fact, it’s going to take all of us pulling together to make the situation significantly better by making changes at the personal, political, and cultural level. It may start with you, but it can’t end with you…” It’s about building a better world for the people we’re raising, and raising the kind of people that world needs.