April 10, 2019

I didn’t rally on Queen’s Park in 1997

I didn’t rally on Queen’s Park in 1997, the last time an austerity government set its sights upon Ontario’s schools and teachers fought back. In my defence, I was a student in my final year of high school. And if walkouts were being organized, I didn’t notice. I recall thinking that politics shouldn’t concern me; surely the adults could work it out? I didn’t understand that teachers were standing up against policies whose destructive effects would be felt for generations.

And this is not hyperbole. When my child began kindergarten in 2013, elementary schools were very different from what I remembered. Apart from the implementation of full-day kindergarten, it has been decades since major investments were made in Ontario’s education system, a system whose underfunding was signed into law in 1997 when Mike Harris’s government changed the funding formula, the policy my teachers were rallying against.

Which is why these days, teacher-librarians work half-time, if at all. At my kids’ wonderful school, we don’t have a vice-principal, or a music teacher. Parents volunteer in the office to help our lone administrator keep up with her tasks, and they also tutor students in literacy programs. Parent fundraising replaces decades-old gym mats, replenishes classroom libraries, and leads initiatives to redevelop school playgrounds. Education Assistants and other support staff are rare in classrooms, while teachers—carrying on heroically—face growing numbers of students with special needs.

Meanwhile, Ontario schools—literally—are falling apart, facing a growing $15.9 repair backlog. In 2016, thanks to advocacy from grassroots organization Fix Our Schools, the Liberal government committed to $1.1 billion for school repairs, which was a start, but not enough. And then weeks after their election in June 2018, Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives eliminated the Cap-and Trade program—“Promises made, promises kept,” Ford and his ministers crowed—the school repair fund disappearing with it.

So this is the system the government is looking to cut from to pay for overpromised tax breaks. When high school students walked out of classrooms on April 4, they were standing against pedagogically unsound ideas including increased class sizes, mandatory e-learning, the elimination of thousands of teachers, and specialized programs and classes. At the elementary level, junior class sizes are rising, teaching staff are being laid off, special grants and programs are eliminated, along with plans to implement Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission into the curriculum, and there has been no additional funding for students who’ve lost support through the province’s autism program.

The students who walked out—the Premier dismissed their organizing as coming “strictly from the union thugs”—are so much more aware of their world than I was at their age.

“I heard about the cuts and I was just kind of mulling it over for the weekend,” said Natalie Moore, 18, who organized the walk-out. “I kind of realized that students, especially as leaders, need to step forward and take it into our own hands.”

And on April 6, two days later, thousands of teachers, parents, children and allies—galvanized by students’ actions days before—would do the same, gathering at Queen’s Park to stand against cuts to schools and this government’s unwillingness to invest in public education.

It was another demonstration that Ford and Thompson would write off as a union stunt, but I was there, and I’m not in a union. Neither are my neighbours, my children, their classmates, and parents and grandparents who gathered in a downtown playground on Saturday morning so we could walk to the rally together. We were there to stand with our teachers—our partners in our children’s education—and because we believe in a well-funded education system where every child has a chance to succeed.

For me there was another reason to rally at Queen’s Park, and it’s to make up for my failure to do so two decades ago. I see a direct line between my inaction then and the ways my children are being let down today. They deserve an education as excellent as the one that I received in Ontario schools, as do all those students who walked out of class last Thursday, those with the courage and conviction to use their voices and stand up for schools, and not simply wait for the adults to work it out.

And we are the adults now. So let’s fight back, and finally be the kind of people that Natalie Moore and all our children can be proud of. They’ve set the most incredible example for us to follow—and we’re proud of them already.

Next steps: Ontario parents with school-age children: the group West End Parents For Public Education Toronto has created an incredible tool kit that we are using at our school to rally together and fight back against the government’s attack on public education. Please take a look at it!

- If you’re on the council at your child’s school, there is lots of practical advice and things to do—and if your council is not political, let me tell you that ours wasn’t either but I’ve found lots of support from my colleagues on council as we take action for our kids.

- If you’re not on council, you can still organize (and possibly the people on your school’s council will be happy someone else is doing it!).

- And if you do not have the time, please reach out to your school’s council and let them know that these issues are important to you and make sure they know about the WEPPE tool kit.

- To those of you whose children go to private schools, I hope your communities will also think of ways to be allies for public schools and support this cause.

An important thing I’ve learned in the last year is that you don’t need to wait for permission to start acting on the issues that are important to you. Please reach out if you have any questions or would like to work together.

April 9, 2019

Canadian Independent Bookstore Day: A Modest Proposal

Independent Bookstore Day is an American celebration that takes place on the last Saturday in April, and in 2015 Canadian novelist Janie Chang brought the concept north of the 49th parallel with Authors for Indies Day, which brought authors into bookstores (and there was often cake) to hand-sell their bookish favourites. I took part at a local bookstore the first two years, and then in 2017 I jumped into a van and took off on a bookish road trip, which was epic fun. And in 2018, the project was taken over by the Retail Council of Canada, rebranded as Canadian Independent Bookstore Day. Gone was the author focus, partly because some authors didn’t comprehend the point of being in the bookstore wasn’t necessarily to sell their own books but instead to be fostering book culture (and buying) in general. Partly also (and you should probably sit down, this is going to hurt): the average Canadian author live-in-person doesn’t necessarily turn out a crowd. If you are the exception to this rule, I urge you to get yourself to a bookstore on the last Saturday. Bookstores need crowds. Out the door, popular people. DO IT.

But if you are more like the rest of us, with a respectable career but not (YET) with a cult following, then I’ve got a modest proposal for you. I’m not sure what’s going on with Canadian Independent Bookstore Day this year—the website seems to be down and I’m not even sure what the name is (Independent Bookseller Day in some circles?) let alone the hashtag. But I’ve already been hearing some buzz and in the spirit of projects that rely on community spirit, little work and no overhead (SO my jam), please hear me out.

If you are a Canadian author, and/or anyone who appreciates a vibrant literary culture (who doesn’t?), then head out to an independent bookstore on Saturday April 27 and spend some of your hard-earned cash.

If you have children in your life, bring them too and let them pick out a book or two. If you have people in your life celebrating birthdays in coming months, do your shopping then. If you’re thinking of end-of-year teacher gifts, pick up some gift cards. If you’re being urged toward-self-care from all quarters, buy a big stack of novels you’re dying to read and consider the job done. If you can’t think of what you’d like to read, ask the bookseller for a recommendation (or take my quiz to find your perfect literary match!). If you don’t have much money to spare, buy a paperback kids book for under a tenner. If you don’t have cash to spare at all, you can write your bookseller a thank-you note letting them know you appreciate their place in your community, and go in to drop it off. There might even be cake?

The sole advantage to not having your own local independent bookstore is an excuse for a road trip. Here are some bookshops I’ve come to love on my travels. In a recent Twitter thread, Monique Gray Smith was also sharing some of her favourites. I have found in my experiences that bookstores can often be found in proximity to great places to have lunch…

Writing books or working in publishing is one of the least lucrative jobs a person could spend her life trying to succeed at, but I still think that buying (full priced) books (from businesses that contribute to a healthy literary eco-system) is part of the job description, when you are able. You might be a writer, but you were probably a reader first, and if we aren’t buying books, well, who else is going to? This goes for book bloggers, who may become so inundated with review copies that it’s hard to seek out book purchases. But still, the most surefire way I know to get people buying books is to…go by books myself. (Done and done.) Let’s see how much of an influencer you really are. (Finger crossed: SO MUCH).

Let’s all be the bookshop customers we wish to see in the world! See you on April 27.

“Buy hardback fiction and poetry. Request hardback fiction and poetry as gifts from everyone you know. Give hardback fiction and poetry as gifts to everyone. No shirt or sweater ever changed a life. Never complain about publishing if you don’t buy hardcover fiction and poetry regularly.”– Annie Dillard, “Notes for Young Writers”

April 8, 2019

Gleanings

- If you’ve heard me talk about the library, you’ll know that I value the photocopier as one of the unsung heroes of human exchange.

- 17 Strategies of a Born-Again Reader

- It’s time for the men to listen and to record and to stay quiet.

- You get what you get, when you get a child.

- Choose Kindness! Kids Books that Explore This Crucial Value

- But where it comes to that question – the one of whether or not to bring new life onto the planet, by way of my body – I and my presently fertile peers have chronologies to consider beyond our own.

- When I was first diagnosed I turned to Jilly Cooper…

- How an Email to an Astrophysicist Changed My (Book’s) Life

- Think about how things like desolation, sadness, an imbalance in the universe, even, have a way of sharpening us, too

- …we’ve allowed our friendship to steep and stew, to mature; gathering dust at times, shining brightly at others. Never discarded. Complex, still vital, preserved and cherished.

- The water and its glorious buoyancy makes all of us athletes.

- Lord Peter Wimsey, from the beginning

- Although I was often warned about getting Blasenguitar and I understood from the way she said it that it was painful and I would be sorry, she never explained what it was.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

April 5, 2019

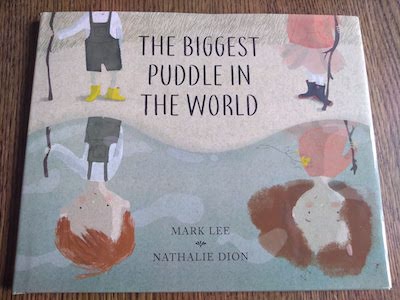

The Biggest Puddle in the World, by Mark Lee and Nathalie Dion

I’ve been meditating a lot on connection lately, how one thing leads to another, the ways that small things can cumulate in big things—which is the underlying message of The Biggest Puddle in the World, by Mark Lee and Nathalie Dion. But it’s a message that’s buried deep inside a wonderful old-fashioned story about two siblings who go to stay with their grandparents (Granny B. and Big T) for six whole days while their parents are away. In beautiful illustrations rich with gorgeous mismatched prints (damask wallpaper, floral duvet, mattress stripes to die for) we’re shown the siblings exploring their grandparents house as the weather outside just rains and rains and pretty soon the two are out of playtime options. But then: “The next morning patches of sunlight appeared on the kitchen floor.”

And so they head outside wth Big T. with a challenge: a search for “the biggest puddle in the world.” “The wet earth and the shiny grass smelled like spring. During the rain, a clump of mushrooms had popped up on a log.” They find one puddle, and then more puddles, but none of them constitute “the biggest puddle in the world.” Their grandfather encourages them, “Follow the water,” and they do, as the trickles from puddles turn into a stream, and then a pond. And they take a break from searching to create a puddle map, and then learn how puddles turn into clouds, which are made from bodies of waters everywhere, including that still-elusive big puddle that they’re looking for. Which they find by following a river through thorn bushes and down a muddle hill to reach a beach, and there it was: the ocean. The biggest puddle in the world!

The prose is lovely to read and the illustrations soft, dreamy and detailed, as absorbing as the story is. Just the book for April, and all its showers—it’s a perfect springtime read.

April 4, 2019

A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Alicia Elliott

One of the first essay collections I ever fell in love with back when I was first falling in love with the essay was Pathologies, by Susan Olding, who was later kind enough to write a short piece at 49thShelf about the essay form. Olding wrote, “In an unstable world, we want to know what we’re getting, and with an essay, we can never be sure. Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.”

It might be the risk, but it’s also the reason, as demonstrated by Alicia Elliott’s remarkable and now-bestselling debut, A Mind Spread Out On The Ground. A collection of essays that examine stories and ideas from all angles, not one side, or even (more importantly in this age of polarization) both sides, but instead acknowledge a myriad of viewpoints, or points of consideration. These are essays that resist certainty, neat conclusions, simple morals. Instead: there is multiplicity, complication, tension, and this is what makes the book so fascinating. “Sontag, in Snapshots” begins with self image and photography; and then photography and colonialism; Black Lives Matter and video recordings of police brutality; on photography and agency, and also community; cultural stigma of “selfies” and misogyny, and imperial beauty standards; and photography as “a family building exercise;” then landscape photography in Banff vs. the Kinder Morgan pipeline and how some mountains are more worthy than others; and torture a Abu Ghraib; revenge porn; and what it means to have one’s pain witnessed, corroborated. It’s an essay that ends with questions instead of answers, ever expansive, “Why do we need our lives to be witnessed? Why do we need to share our experiences, to have this connection to others? Why do we need to control others so badly and so completely that we will even try to control their image? Is it because we’re trying to make ourselves more real? Is it because that power—as expansive or minuscule as it may be—fills a void?”

As Olding writes, “the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go.”

While Elliott’s essays—which portray her experiences growing up in poverty, as an Indigenous woman, as the child of a mother with mental illness, a teenage mother herself, a survivor sexual assault—recall (in the best way) the groundbreaking work of Roxane Gay in her collection Hunger—a collection that also lays bare the experience of trauma—they are also different in tone. While rawness is a feature of Gay’s essays in her collection, Elliott’s are more processed, polished, synthesized in a way I hadn’t entirely been expecting from someone who (admittedly, in addition to winning magazine awards, being awarded the RBC Taylor Emerging Writer Prize, being nominated for the Journey Prize, and appearing in Best American Stories, so we should have seen it coming) has made a name for herself with incisive Twitter threads and having none of your racist bullshit on that particular social media platform.

But with her first book—which is eminently readable, absorbing and hard to put down—Elliott solidifies her reputation as a profound thinker and prose stylist, in addition to being a Twitter powerhouse. Perhaps the tweets are where her rawness is, but readers of her essays will find a voice more cool and discerning, and oh-so-fucking smart. Good luck trying to mess with “Not Your Noble Savage,” a consideration of literary colonialism that is coming at you with receipts (as they say on the Twitter), with Margaret Atwood in an essay claiming that Pauline Johnson (as an Indigenous writer) is not “the real thing,” but Thomas King (“the son of a Cherokee father and a Swiss, German and Greek, ie white, mother”) gets to be. “[L]et’s consider Canada’s history of dictating Native identity,” proposes Elliott, and then this leads to considerations of how Indigenous writers’ work is “policed” by critics, and the charade of reconciliation, and “the fairy tale that keeps Canada’s conscience clear.”

Recalling Olding’s, “We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave.”

Oh, the places where these essays take us. She writes about learning the verdict in the Gerald Stanley case, on trial for the killing of Colten Boushie, while visiting the space centre in Vancouver while on vacation with her family, “dark matter” as a metaphor for racism—”it forms the skeleton of our world, yet remains ultimately invisible, undetectable.” I haven’t had lice since February (knock on wood) so was able to read her essay “Scratch” without too much creepy-crawly imaginings. She writes about mental illness, and the Mohawk phrase which describes it, which is where Elliott’s collection gets its name. About being Indigenous while looking white, and her ambivalence about her child receiving the same inheritance; on cultural appropriation and what it meant when she read Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, the first time she’d read the work of another Indigenous woman—she writes, “Every sentence felt like a fingertip strumming a neglected chord in my life, creating the most gorgeous music I’d ever heard.”

I’ve not even touched on her essay about Toronto’s Bloor and Lansdowne neighbourhood, about gentrification; the one about nutrition, poverty and its colonial legacy; about her marriage (“Antiracism is a process. Decolonial love is a process. Our love is a process…”) About attempting to understand and love her complicated and troubled mother. Her essay, “Extraction Mentalities,” which is a “participatory essay,” something I’ve never encountered before, with literal space on the page for the reader to engage with her questions. And throughout the entire book, really, Elliott has created space to engage with her questions, the entire project infused with this characteristic generosity. To be at once fierce and powerful, but also vulnerable and tender—what a gift that is to her reader. And what a gift this whole book is, strumming a neglected chord that the world needs to hear right now.

April 3, 2019

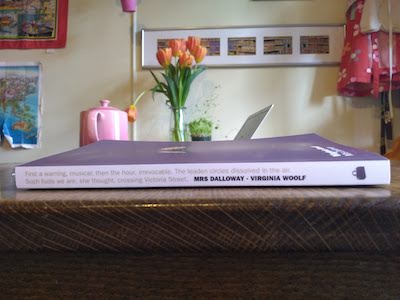

Mrs. Dalloway: Redesigned

I like to read in a stream of literary consciousness, unplanned, meandering, one book leading to another in an organic fashion that I need not think about too deeply, but it just makes sense. My logical mind is not in charge of it, though things like library due dates factor in, and also whether or not a hardcover will fit into a particular handbag, or just how appropriate a book might be for the beach. But for the most part, I let the books decide, like how I was finishing up All the Lives We Ever Lived last week, and then Mrs. Dalloway turned up in my mailbox.

Mrs. Dalloway is the latest release from Ingrid Paulson’s Gladstone Press, which also published The Age of Innocence, a book I read over Christmas and turned me into a full-fledged Gladstone Press enthusiast. And when I heard that Mrs. Dalloway would be the first of their 2019 releases, I was ecstatic, because I love this book. a book I’ve returned to several times since I first learned to read Virginia Woolf (for me, it was not instinctual) twenty years ago when I was an undergraduate. It’s funny, because while I like to read in a stream of literary consciousness, the act of actually reading stream-of-consciousness is not my ideal. Because it’s hard and you have to pay attention and nothing’s fastened you to the plot so you have to do all that work yourself.

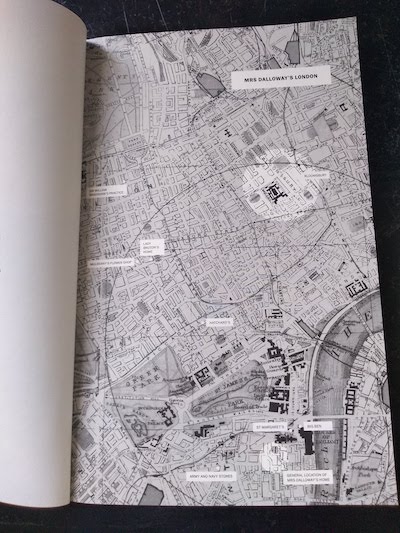

But I can do it with Woolf, with Mrs. Dalloway. Not getting too caught up in the details, letting the atoms fall where they may. It takes practice, and confidence, and patience, but I find it so rewarding. And easier too in a book that’s brand-spanking new, with a map even (my second-hand Penguin paperback that had once belonged to someone called S. Hull, according to the title page, didn’t have that) so I could follow Mrs. Dalloway, and Septimus Smith, and Peter Walsh through the streets of London, through the hours of day in June, right up to the party. For which Mrs. Dalloway had bought the flowers herself.

Gladstone Press books are available for purchase via their website, and are also currently for sale at Type Books on Queen Street West in Toronto. And as for me, my walk with Mrs. Dalloway led next into a walk with Alicia Elliott in her extraordinary and now bestselling essay collection A Mind Spread Out On the Ground, and then to Anna Burns’ award-winning Milkman, which is another walking book. And I’ll keep you posted as to where my literary journeys take me next.

April 2, 2019

A Deadly Divide, by Ausma Zehanat Khan

It was uncanny to be reading Ausma Zehanat Khan’s latest mystery A Deadly Divide, a novel about a (fictional) mass shooting at a mosque in Quebec. For obvious reasons, of course, after the terrorist attack in Christchurch, but also because of the voices that are a part of Khan’s narrative in this novel, her fifth one about Detectives Esa Khattak and Rachel Getty, who work as part of a “Community Policing” team investigating crimes involving immigrant communities. (In her previous novel, A Dangerous Crossing, the detectives end up on a Greek island investigating a case involving trafficking Syrian migrants; the first book in the series, The Unquiet Dead, was about the 1995 Srebrenica massacre; Khan holds a Ph.D. in international human rights law).

“I wrote this book because I have long studied the incipient and incremental nature of hate and the fatal places hate often takes us,” Khan explains in her Author’s Note. “I wrote it to illuminate the connections between rhetoric, polemics, and action. To suggest that the nature of our speech should be as thoughtful, as peaceable, and as well-informed as our actions.” The novel includes online conversations between users on a white supremacy chatroom, conversations which one might call “vividly imagined” on Khan’s part in how entirely lacking they are in imagination—or empathy, or understanding. The lines being blurred between fiction and reality as I was reading this book, as I was reading comments from the Yellow Vest Movement’s Facebook pages. The dangerous rhetoric out there, and it’s terrifying, Khan connecting the dots between the things people post and write, all the supposedly harmless provocateurs—her novel features a radio DJ who relishes pushing boundaries and buttons—, the oh-so principled free speechers for whom the right to say anything at all trumps the right for other people to be unthreatened in the places where they live.

Esa and Rachel arrive in Gatineau in the aftermath of the mosque shooting, where a Priest who was found holding a gun at the scene has been released, and a Black paramedic who was praying at the mosque and went back inside after the shooting to help his friends has been arrested. Meanwhile Esa and Rachel an old friend, a student at the local university and a civil rights activist whose work has been catching the attention of a white supremacy organization on campus. And the activist’s ties to the leader of that organization are complicated, and so are Esa and Rachel’s relationship with the head of the police team they’re working with in Quebec. Who is to be trusted? Khan doing her best job yet in the series, I think, of plotting out twists and turns and always keeping her reader guessing—so that this book, which is a social treatise, turns out to also be a riveting detective novel at the very same time.

April 1, 2019

The Narrative Value of Abortion

I am still not finished writing about abortion (or talking about abortion), not least because writing about abortion/ de-stigmatizing abortion / acknowledging abortion as ordinary is more important than it’s ever been with women’s reproductive rights and access to abortion under threat in a way I never anticipated they would be when I had my own abortion 600 years ago and even had the nerve to take my access to abortion for granted—how very 2002/”post-feminist” of me, right?

And there, I just used “abortion” eight times in a sentence, which I think was the general guideline put forth by Strunk and White in their Elements of Style. Something along the lines of, “Write abortion eight times in a sentence, then go do seven impossible things before breakfast.” (For six and under, you’re pretty much on your own.)

I keep writing about abortion because people with no experience of abortion keep trying to make laws about abortion, and the tyranny and injustice of that terrifies me. But I also keep writing about abortion, in fiction in particular, because it’s really interesting from a narrative point of view. As Lindy West writes in Shrill, ‘My abortion wasn’t intrinsically significant, but it was my first big grown-up decision—the first time I asserted unequivocally, “I know the life that I want and this isn’t it”; the moment I stopped being a passenger in my own body and grabbed the rudder.”’ And from a character-development standpoint, such a moment is pure gold for an author, along with the nuance and ambiguity that comes with the experience of abortion. The defiance, the agency, the courage—these qualities are what character is made of. And the variable ways an abortion is experienced by a couple too, if the pregnant person finds herself in that kind of arrangement. How it could bring two people together, or push them apart, or make clear a reality that’s been present all along.

The possibilities are endless, as to what can happen to a woman (fictional or otherwise) who has an abortion, and endless possibilities are kind of the whole point of abortion anyway. And not that all those possibilities are free and easy—what choice in any life ever comes with such certainty? But it’s about plot and richness and tension and balance, and knowing that a single thing can have two (or more) realities, that a reality can be true and not true at once, which is the entire jurisdiction of fiction.

So I am not finished putting abortion in my work, because of the fact of abortion in the world, regardless of whether or not it makes you uncomfortable. And maybe in this instance, your comfort is not the point? Instead, for the reader, finding abortion in our fiction brings home the ordinariness of abortion in the places where we live—our homes, our families, our small towns and big cities. Writing about abortion is not a question of changing the world, but instead of catching up with it, acknowledging the reality what life has been like all along.

April 1, 2019

Gleanings

- I am rereading Emily of New Moon because of Russian Doll.

- It only took 50 very nice, polite people, including several kids, to…disrupt his agenda.

- To rescue even one child with learning problems or special needs from humiliation in the classroom and at home and from lifelong feelings of low self-esteem, is exhilarating.

- Consider how different our public policy outcomes would be if lobbyists, government-relations professionals, and former political staffers did not dominate the newspaper columns or the evening punditry panels.

- I was opening a tin of mushroom soup for lunch today when this warm wave of recollection washed over me.

- A woman’s wisdom comes, in part, from the great juggle of her life.

- I lose the thread, I miss the connection, I falter, I am lost. What just happened?

- When I wake in the night, I have the sense that everything I know is connected, that I need to find way to stitch it all together like a useful and beautiful length of tapestry.

- But sometimes, I just need them to be game. Sometimes, I just need it to to be easy.

- and the best unexpected gift of all this is how the organization of it makes me feel like I suddenly live in my very own bookshop…

- I feel like this book is so tightly bound to the bookstore, and to your understanding that readers needed a book about a life crisis that didn’t result in hiking the Pacific Crest Trail.

- Paradox: How to be proud of and show off one’s work without being offensive. Not an easy task, not by a long shot!

- Being funny is, in a number of key respects, incompatible with conventional femininity.

- I’ve given up that mythical “trying to strike a balance in life” thing, and now I really just strive to not be shattered into a million pieces.

March 29, 2019

Nature All Around: Trees, by Pamela Hickman and Carolyn Gavin

My nine year old daughter Harriet knows everything, and she continually surprises me. Because who was it that taught her about constellations, garden slugs, axolotls, or the life cycle of a piraña? It wasn’t me, who still sometimes gets tulips and daffodils mixed up, and didn’t actually know what an iris looked like until after I’d given that name to a human. But it’s not altogether a mystery, where Harriet gets her knowledge from, because she’s an avid reader of nonfiction, devouring the “Do you know…” series from Fitzhenry and Whiteside, and Elise Gravel’s “Disgusting Critters” books. Every time we go to the library, she picks up another books about animals or plants—for a while she was really into fungi. (She also really likes Jess Keating’s books, her nonfiction and her novels alike.) But I have to confess that with some rare exceptions, children’s nonfiction books don’t really do it for me.

But then along comes Nature All Around: Trees, by Pamela Hickman and illustrated by Carolyn Gavin, a book that has been given a permanent home on our coffee table. Because it’s gorgeous, just the thing for those of us who are wild about botanical paintings, and a sensibility not dissimilar to Leanne Shapton’s beautiful Native Trees of Canada (with a sprinkling of Carson Ellis and Esme Shapiro).

I love this book! It’s beautiful just to leaf through (ha ha) with its paintings of leaves in their glorious variety, and filled with fascinating tree facts, the difference between a simple leaf and a compound leaf, explanations of photosynthesis, pollination, and features on “strange trees” like the 23-story tall sequoia that’s probably 2000 years old, or the larch tree, which is special because it’s coniferous and deciduous at once.

The terrible thing is that because I am not nine, my mind is a sieve, and I can never remember anything, which is a good excuse to keep this book on the coffee table—in addition to its pleasing aesthetics—because then I get to read it over and over again.

PS Another tree book I’m super looking forward to this spring is Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests, by the amazing Ariel Gordon.