May 10, 2019

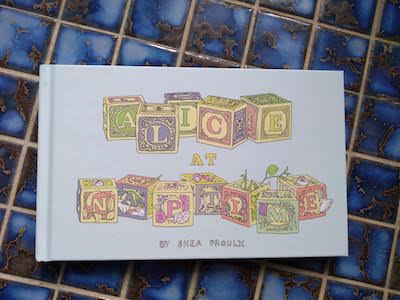

Alice At Naptime, by Shea Proulx

Sometimes I think that the story of motherhood is too big to fit onto a page, or into a book. Because having a baby is this way, and it’s that way, and it’s never one way, ever changing, impossible to properly articulate. Heather Birrell writes about this in her essay “Truth, Dare, Double Dare” in The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood. She writes:

“The trend..is toward a certain gross-out honesty—a “come join me here in the trenches” mordancy (“I just let her chew on the stroller tire!”) which, although funny and often a welcome release, leaves out the deeper resonances and rewards of being a mother and co-parent. Why is this? Because it’s hard to put your finger on the glint of joy in the dirty dishwater of drudgery. It slips away, seems a trick of the light, impossible to photograph, let alone articulate.”

But maybe you can draw it?

I am under the spell of Alice at Naptime, by Shea Proulx, who wrote in a post for 49th Shelf:

Drawings not only make clear the path of the body, but also the path of the mind, as text does, but differently from text. The world “psychedelic” is most associated with mind-altering substances, but the word breaks down from the Greek to mean “the mind…made clear.” Works of art that show clearly the mental processes involved in thinking through a subject might also be described as psychedelic, especially when the subject is inexpressible in words…

Alice at Naptime is a series of illustrations that Proulx drew of her daughter when she was a baby. “I used to draw all the time..” the book begins, “but now just at naptime.” And when Alice is napping, she draws Alice, her sleeping face set into kaleidoscopic scenes, a wonderland of strangeness, symmetry and doubleness that grows to fill the entire spread: “a symphony of Alices.” A kind of dreamland. And fittingly, for a child named Alice with illustrations that are definitely trippy, there is wonder: “Alice is strapped down so often when she naps. It looks like we’re worried she might float away.” What does Alice dream about? Proulx asks the reader, “Am I boring you?” And I remember the fascination of my sleeping child’s face, the smallness of my world then—I remember the day my child discovered causality while kicking an arch on a baby gym, and both our minds were blown, but nobody else cared. “It’s just that I’m so in love,” Proulx writes, “lost in a sea of Alice.”

What I love about this book is how Proulx shows the way that motherhood can inspire art and thought and creativity, rather than be its antithesis. That there is such profound love in the minutiae of parenting. It is like a dream, like a storm, rolling waves—and she started thinking about Alice growing, wondering who this sleeping baby will grow to be. (“What would it be like to wake up in different places all the time?”—but motherhood is a little bit like that as the years go on. My daughter turns ten this year. She’s known about causality for awhile now. Every day, we’re somewhere new.)

“I take Alice with me everywhere, even when I leave her at home.”

“Love can seem like a trap,” writes Proulx, confined to the place her baby is napping, to her baby’s needs and whims, “but I have roots now.” And it becomes clear that this book about a baby growing into a person is fundamentally the story of a woman growing into a mother—and also how she acknowledges that these sleeping napping days with Alice were only just a blink of an eye. (A dream?)

In a gorgeous afterword, Proulx writes about how it’s been years since she made these drawings. “I’m not the person I was then. You don’t become a mother all at once. You have to grow into that new self. I recognize the fragility of the tenuous identity I was sorting out as I relaxed into a new rhythm… It isn’t without sacrifice that women become mothers, or men fathers. But the gains are heady and by their nature, indescribable, as are many natural desires. I only hope I’ve done the process some small justice. I owe that to a former self, that new mom, adrift in a wonderland, wondering who she would become.”

May 10, 2019

On Mother’s Day, I’m Grateful for My Abortion

I posted this two years ago, but I feel it even more profoundly now. While people who want to restrict abortion enrage me, I also manage to feel pity for the smallness and lack of complexity of their world view, to have the limitations of their understanding on display so flagrantly.

I also had the chance to answer some questions about the essay anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, five years on from publication. You can read it over here.

On Mother’s Day, I am grateful for my abortion. Which might sound intentionally provocative, but it isn’t. If you think very hard you might be able to fathom the banality of being grateful for this one thing upon which my adult life has hinged, from which everything since has come from, every single ordinary wonderful thing. Although I wasn’t always grateful—at the time such a thing as gratitude never occurred to me. To have the freedom to make a decision about my own body and my own destiny—that sounds kind of banal as well. It was 2002 and things were politically different, or at least I was isolated enough to think they were. At the time it wouldn’t have occurred to me that The Handmaid’s Tale was prescient.

But none of that is actually what I’m thinking about today, in 2017, amidst the conversations about cultural appropriation I’ve been listening to all for the last few days—except for yesterday when I took a blessed internet sabbatical. Instead, I am grateful for my abortion for another reason, for the ability my experiences of abortion and motherhood have given me to grasp nuance, hold uncertainty and hold two ideas in my head at once. “A single thing can have two realities.” My abortion enabled me to articulate this idea, to come to know the necessity of in-betweeness. It’s a point of view that many people a great deal smarter than I am have still not been able to grasp.

I was thinking about this this morning as I read [Redacted; a person not worth thinking about specifically]’s remarkable twitter timeline which must have originated in defence of her son who has been called out for supporting a “cultural appropriation prize” in defence of another editor who has (seemingly) been set-upon by the twitter mobs. I’ve never seen such an example of one misguided offensive thing spiralling into a whirlwind of absolutely abhorrent behaviour, the kind of behaviour that would embarrass a daycare room of toddlers, with apologies to toddlers. [Redacted] daring to make a terrible thing even worse by for some reason claiming that positive experiences of Indigenous people in Canadian residential schools had been censored from the official report, which [Redacted] hasn’t even read. (“Is there no subject matter you don’t know about that you feel qualified to opine on?” asks Maggie Wente on Twitter.)

It was all so preposterous that I did the thing that no one should ever do, which is click over to [Redacted]’s timeline where she was retweeting some guy who’d tweeted, ‘Nothing says “I love you, mom” like a child you didn’t abort.’ And here, I thought, was exactly the problem. A person who’d think that was the reality of abortion and motherhood would be the person limited enough not to understand how one could support free speech and respecting Indigenous cultures. Not to see that Black Lives Matter means that all lives matter. The kind of person who doesn’t seem to get that you can find female genital mutilation appalling and still not be a raging racist, or even be a feminist who supports the right of other women to do what they like with their bodies—adorn it with a headscarf, even. That women who have abortions might be the same women who’ve mourned miscarriages, or who celebrate life-saving techniques that make it possible for babies born as early as 23 weeks to go on to thrive. These are also, I must point out, the same people who REFUSE to understand that most late-term abortions are performed on babies that were desperately wanted but nonviable due to fetal abnormalities. People who don’t get that a person like me who was so grateful for her abortion at six weeks can understand that for many women “choice” can be the lesser of two tragedies.

I am grateful for my abortion, because my experience as a pro-choice woman has informed so much of my understanding of power structures and oppression . It’s why I’m not sure “debate” is the answer, because I’ve had to stand on the street corner “debating” my bodily autonomy with a twenty year old Catholic boy, and I’m not sure it really got me anywhere. It’s why I know that “Yes, but…” is usually a better answer, and that sometimes we have to acknowledge that people really are the experts on their own lives and experiences. That listening is usually the best course. That we all have a lot to learn from each other. That sometimes the things that make us uncomfortable are the real things, and that grey areas exist for a reason and we have a lot of discover where they do.

If not for my abortion, I might think that questions have easy answers, that the world has easy answers, that life is uncomplicated, tidy and straightforward. I might not even understand that this can be true: if not for my abortion, I wouldn’t have my children. So on Mother’s Day, I’m more grateful than ever.

May 9, 2019

The Countdown is On

I have had a busy week as we finished the website for my TOP SECRET BOOKISH PROJECT, which launches on June 3. (The countdown is on.) I also put up a brand new literary matchmaking quiz and am pleased that response has been as enthusiastic as it’s been to the first one. And I’ve been working on Blog School too, which is going to have a site of its own soon, but in the meantime, the info I’ve made so far has been expanded, and I am excited. And I am excited, which is my favourite way to be, always counting down to something. (Overthrowing the patriarchy is next up on my list.)

May 7, 2019

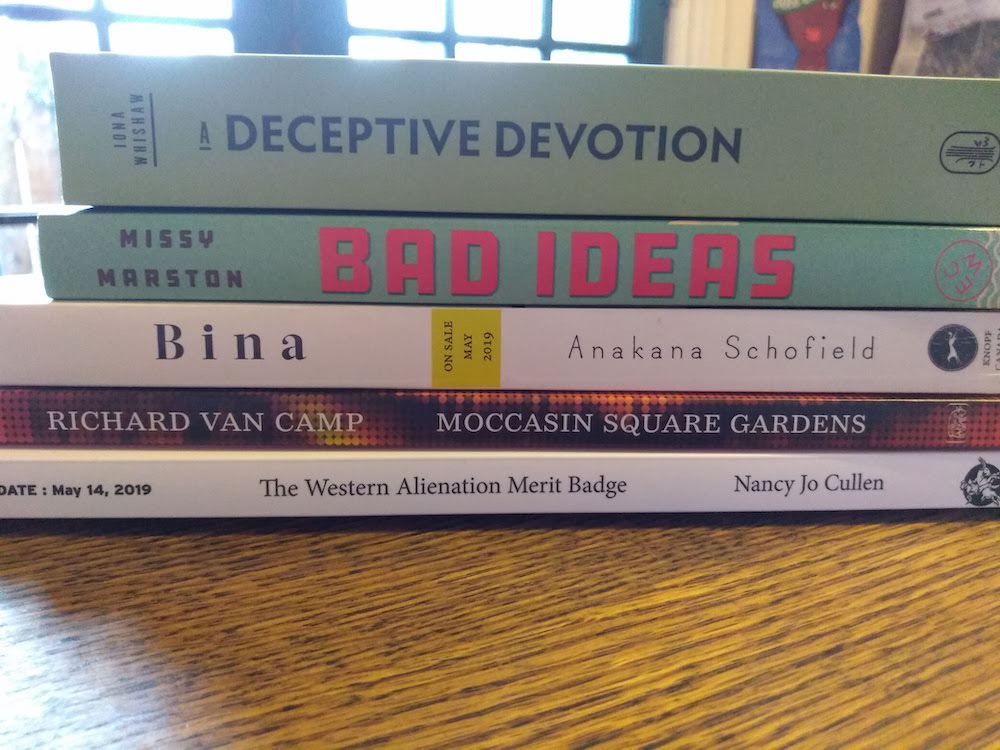

New Lane Winslow Alert

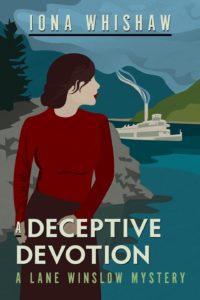

Has it only been a year since I fell in love with Lane Winslow and Iona Whishaw’s wonderful series about the best lady sleuth since Harriet Vane? Set in the interior of British Columbia during the post-WW2, these novels about a young woman who just happens to be an ex-spy—and who would like to retire for a little peace and quiet, please, in the idyllic hamlet of King’s Cove—are as smart and feminist as they are charming, which is saying something. And their underlying messages are so timely and relevant still decades after the time in which the series is set.

My Lane Winslow career started with the fourth book (which was amazing!), and then I spent last summer getting caught up on the back story, just in time for Book Five to come out in the fall. And now Book Six is here, A Deceptive Devotion, as Lane and Inspector Darling plan their wedding (swoon) but (naturally) they stumble upon a murder (the murder rate per capita in King’s Cove rivals that of Midsomer) and things get complicated…

I had the pleasure of providing an endorsement for this book, which I read back in December. “It’s always a pleasure to return to King’s Cove and be swept away by another Lane Winslow tale. This latest instalment—rich with intrigue, humour, murder and romance—underlines why Whishaw’s books have fast become my favourite mystery series.”

May 6, 2019

Gleanings

- I don’t mind hearing the word, bravo, but nor do I need it.

- Make no mistake, there is no charity in stirring hatred against your neighbour whatever language they speak in their kitchen. It is a stingy and self-serving ploy to separate us from each other. It puts everyone in a great danger.

- I am in that river of consciousness now, at this point in my life, deep in its waters, sometimes chilly and in danger of losing balance in the current, sometimes so utterly joyous that I have to pull myself back to the shore by force of will.

- But I’m a woman, so I’ve always been aware that what I like is not what everyone likes.

- The urge to leave a mark on a wall, in the sand or on on the radiators, as I once I did, is so instinctively human.

- I think the marvellous is there at all times, and we just have to be in the correct state to peer into the cracks of the universe.

- Yes, I felt porous, the generations coming to rest in my cheekbones…

- If we pour some tea, put on our favourite music, and come to our work saying, “I’m a bit nervous,” it always seems to open up, doesn’t it?

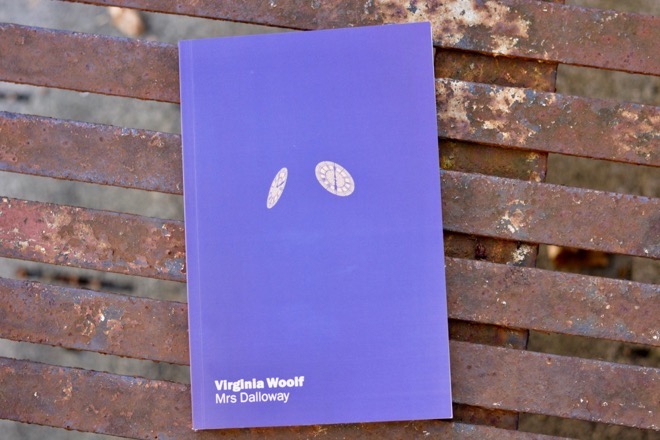

Giveaway alert! I’ve got a copy of Gladstone Press’s GORGEOUS new edition of Mrs. Dalloway up for grabs. You can enter via my Instagram or Facebook pages. If you don’t do either social medium, drop me an email and we’ll sort it out.

May 3, 2019

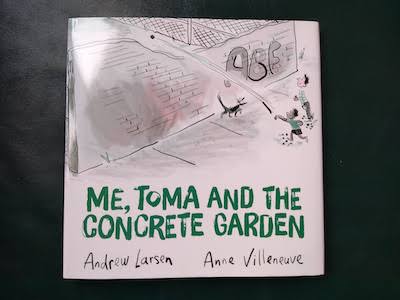

Me, Toma and the Concrete Garden, by Andrew Larsen and Anne Villeneuve

Everything I’m hungry for in the world right now I can find within the pages of my friend Andrew Larsen’s new picture book, Me, Toma and the Concrete Garden, illustrated by Anne Villeneuve. It’s a book about cities and concrete, about connections and community. It’s about the beautiful things we grow by accident, and how small changes can have huge ramifications. But it’s also a story about two kids throwing balls of dirt over a fence, about meaningless fun, and my children like it too, compelled by the wonderful details in Villeneuve’s illustrations and also Larsen’s winsome narrative voice, which is my favourite thing about all his books. He writes voices that really sound like kids, kids who aren’t quite aware that their stories are bigger than the story they think they’re telling. There are lessons and morals in this book, but you’ve got to read between the lines to find them, which is what makes Larsen’s books—beloved by children—especially rich for adult readers as well.

May 1, 2019

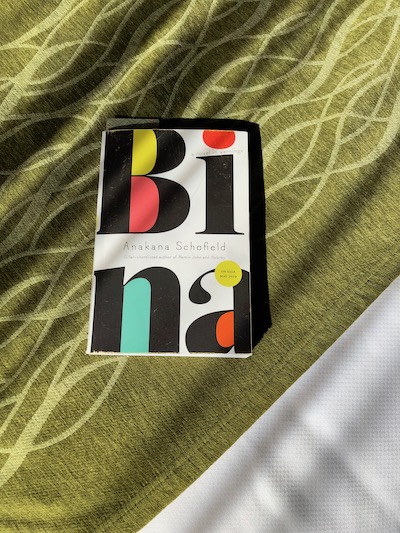

Bina, by Anakana Schofield

Anakana Schofield’s Bina follows Martin John, which was shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2015, and Malarky, winner of the 2013 Amazon First Novel Award, and takes place in the same fictional universe—the character Bina first appeared in Malarky. And now Bina has had enough, we’re told, and really, what woman hasn’t, I wondered. Supposing that Bina had had enough in a very general sense—but there is nothing general about Bina. Instead, this is very much a novel about specificity, and the failure of general terms, common tropes, and lazy thinking to adequately reflect human experiences which makes it very difficult/impossible to achieve real understanding, even in the truest of friendships.

But then one complicating factor in all this (and there are many) is that Bina herself isn’t being very specific. (“How can I say it without saying it?”) Confined to her bed and afraid for reasons she cannot properly delineate (some identifying details are redacted with a thick black line) she is scrawling her story onto the backs of envelopes with whichever writing device she can dig out from under the bedcovers, which explains the peculiar shape of her paragraphs, short lines stretching long. What she’s writing is not so much her story, but a series of warnings, one of which involves the danger of discerning a larger meaning to her narrative project: “Don’t trust a word said after I’ve stopped,” she writes. “…Don’t arrive at the end of this tale insisting it was too long or too wide or too unlike you. I am not interesting in appealing to you.”

But she does.

Some things have happened to Bina—she found a man in a ditch, she delivered Meals on Wheels, she couldn’t get rid of her lodger, she’s been getting violent messages on her answering machine, her best friend is dead, Bina’s been in jail, hippies are camping in her yard, and there’s the Tall Man who comes over and they sit down and play Scrabble. And similarly is the novel itself a puzzle, a kind of wordplay, with blanks to be filled in (but alas, no triple word score). But how one of things that happened to Bina connects with all the other things that happened is not a straightforward kind of crossword situation unfolding line-by-line neatly across the board.

“I often wonder at the women who give birth to awful young fellas like Eddie. I think there’s a case to be heard for shoving the likes of Eddie back up and starting all over again. I believe in abortion since I met Eddie. It’s a shame you can’t abort a 40-year-old.”

There is the most fascinating kind of moral ambiguity in this novel, and it is here where Bina’s lack of interest in appealing to us is most apparent—she keeps threatening murder, though her lawyers implore her not to. She’s not here to deliver any message beyond her warnings, and the novel is most remarkable in its refusal to have a gist and, like its protagonist, to conform to anybody’s expectations. Yes, this is a novel about female rage, and failures of society, how women are ignored and dismissed, but it will not sit tidily in any kind of box. Bina is a novel opposed to boxes.

“Bina’s not for difficult books,” the reader is told. “Life’s full of difficulty, so if she were ever to lie down and take up a book, it couldn’t be a difficult one.”

Bina is not a difficult book. It’s a provocative book, an original book, and it’s challenging, requiring the reader’s engagement and attention, but engaging with and attending to the book is not difficult, even if the protagonist is so determined that she will not appeal to you. Because she does, and her voice is fabulously caustic and it’s almost delightful to follow her, no matter how dark a turn the story is going to take (and it does). And once I got to the end, the puzzle still wasn’t solved, not all the blank spaces filled in yet, and it’s the kind of book that is best read more than once but it’s also the kind of book you will want to read more than once, and the second time I liked it even better.

May 1, 2019

May Books on the Radio

One reason I really love having a books column on CBC Ontario Morning is because of the host, Wei Chen, who has just returned to the airwaves after a leave of absence. She is such a pro, so good at her job, but my very favourite thing about her is that she actually reads the books I recommend on her show. Which means that we get to talk about books in a way that is real, and meaningful, and that is such a pleasure. And I think that pleasure is evident in our conversation this morning, which you can listen again to on the podcast. I come on at 49.00.

April 29, 2019

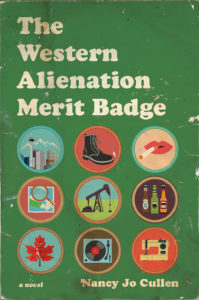

The Western Alienation Merit Badge, by Nancy Jo Cullen

Nancy Jo Cullen’s debut novel The Western Alienation Merit Badge (which follows her award-winning story collection Canary) begins billions of years ago: “After the inland sea dried up and its beaches turned to sandstone and the plant life turned to coal and gas…” Although by the end of the sentence, we’ve arrived in the 1970s, a small girl emerging from the bushes with her cap-gun loaded, a copy of The Guide Handbook tucked into her waistband. But we will not discover just who the girl is or where she’s come from exactly for about 150 pages or so. And the point is this—that while history stretches long here, it’s never out of sight, and everybody’s looking backward, behind them, time unfolding like a peacock’s tail.

Although there is nothing as extravagant as that in the novel’s first section, which takes place in Calgary, Alberta in the autumn of 1982. Which is why it’s particular hard for Frances to be home again, her European adventure cut short because her stepmother had died and her family needed her. Leaving behind her girlfriend and a certain amount of carefreeness in Portugal to come back to Calgary, which has just lapsed into recession. Her widowed father is taciturn and has taken up needlework as a way to connect with his wife, and Frances’s furious sister has problems of her own. So when Frances reconnects with a woman from her past, and her (Catholic) family begins to understand that she’s a lesbian, things go over just about as well as you might expect.

The Western Alienation Merit Badge was a pleasure to read, and in terms of craft is remarkable for two particular features. The first is for its points of view, which move between characters providing vastly different perspectives on the same situation, and while the few times this happened mid-chapter it was a bit jarring, the result of this approach is a complex and multi-layered narrative that is really effective in particular because of how Cullen avoids cliches and sentimentality in creating her characters and their dynamic. There’s no wicked stepmother trope here, as Frances had really loved her stepmother, whose arrival in the household had made their broken unit into a family—and they’re all lost without her. Her father’s grieving process, taking up quilting and knitting and trying to channel his wife through her sewing machine, was unlike anything I’ve ever read in fiction before, and such an incredible way to add an additional dimension to a working class guy, the kind we’ve all read about in fiction before. But will his sensitive side extend to understanding the life of his lesbian daughter?

The other remarkable feature of the novel’s construction is that after a short second section set in 2016, the novel takes us back in time. Not quite as far back as when the inland sea dried up, but instead to 1974, before Frances’s stepmother came into the picture, and here the reader is provided with the solution to much of the puzzle regarding the kind of people who the members of this family would become. Because Alberta is the kind of place, the novel is suggesting, where the answers to questions still lie in the past, which is why this novel set in a recession-era Calgary circa 1983 seems so absolutely timely in 2019, in particular as the province has dominated national headlines lately with their recent election.

If you’re not from Alberta and want to understand why Alberta is the way it is, and the way many people who live there feel about themselves in relation to the rest of Canada, this novel is a good place to start.

April 29, 2019

Gleanings

- Women have a long history of swimming: it’s been socially acceptable for us to be athletes in the pool and open water for much longer than in other sports.

- To me, India’s cells are like starlight —a hint of the brightness that was my child.

- Kiwi-strawberry walked so flavors like green tea and hibiscus could run.

- It’s time to bust these common menstrual myths.

- It’s pretty fierce this love in our house sometimes…

- Podcasters are regularly criticized for what they have to say, but women are also being attacked for how they say it.

- Out went the elaborate meals, and in came the pizza, frozen enchiladas, and instant ramen.

- I’ve read some weird stuff since getting into literature in translation last year.

- I think that when we consider things quite opposite to what is expected, we stay freer and more open to breaking rules. Which is something else we should consider.

- The clutter might not bring me joy, but I’m not an overly joyful person, so that’s okay.

- Good old Jake Addison.

- She says it isn’t magic but I’m not sure any of us believe her.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.