December 11, 2011

Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Kristen den Hartog

When I fell in love with Kristen den Hartog’s novel And Me Among Them last spring, it really felt like a spring, because it was the first novel I’d loved in ages after a long cold winter. The magical elements of her story about a girl who grows to be seven feet tall and is blessed with a strange omniscience were so perfectly countered with a realism that kept the story’s feet on the ground, and the entire effect delighted me, which is remarkable when one notes my aversion to books about freakish sorts (confession: I am of the handful of people who hated Geek Love).

When I fell in love with Kristen den Hartog’s novel And Me Among Them last spring, it really felt like a spring, because it was the first novel I’d loved in ages after a long cold winter. The magical elements of her story about a girl who grows to be seven feet tall and is blessed with a strange omniscience were so perfectly countered with a realism that kept the story’s feet on the ground, and the entire effect delighted me, which is remarkable when one notes my aversion to books about freakish sorts (confession: I am of the handful of people who hated Geek Love).

But it’s because den Hartog’s novel is not about freakishness at all that the story so resonated; instead of staring at the giant girl, we’re given the gift of the world through her eyes, and the view is extraordinary. And the novel is so rich that when I finished it, I wanted to know more.

One Thursday morning in mid-November, Kristen den Hartog came over to my house for some conversation, cheese and baked goods. We tried not to be distracted by the toddler in our midst who decimated the cheese plate and sang made-up songs. What follows is an edited version of our talk, the toddler-centric bits edited out completely (and you probably won’t even notice that at one point here, I was in the other room changing a diaper).

Kristen den Hartog is a novelist, memoir writer, mom, sister, wife, daughter and incredible kids’ book blogger. And Me Among Them is due out soon in the U.S. as The Girl Giant. Her previous novels are Water Wings, The Perpetual Ending, and Origin of Haloes. The Occupied Garden: A Family Memoir of War-torn Holland, was written with her sister, Tracy Kasaboski, and they are now at work on another collaboration. She lives in Toronto with her husband, visual artist Jeff Winch, and their daughter.

I: Where did And Me Among Them begin?

I: Where did And Me Among Them begin?

Kdh: At first it was a short story about parents whose son is a giant and dies of complications from his condition. Much of that early draft focused on their loss and how they tried to get over it. Then I decided I wanted the boy to be a girl, because it presented more complicated body issues. It isn’t easy to be a teenage girl, even with a normal sized body, so I was interested in exploring that, and the more I did it, the more I realized I couldn’t have her die. I didn’t want her to be a victim. I wanted her to be powerful and strong, which is why I told the story as if she was looking down on her life from above, seeing things she couldn’t possibly see. I kept thinking, I know it can’t be that way, but I’m just going to plow through and do it because it feels right. I’m so glad I persisted, because that unusual perspective seems to me the very core of the novel.

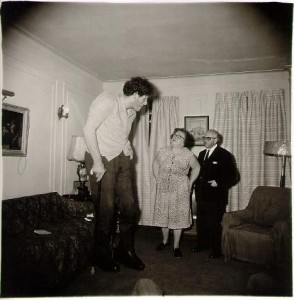

I: I’m also interested in the Diane Arbus photo Jewish Giant at Home With His Parents in the Bronx,  which you mention in your acknowledgements. How did that factor into your creation of Ruth?

which you mention in your acknowledgements. How did that factor into your creation of Ruth?

KD: I’ve known about that photo for a long time. What I love about it is how ordinary the background is and how ordinary the parents are, but he’s just rising up and changing everything by being there.

The image inspired me because of the sheer size of the boy in relation to his parents. But also I thought, when our daughter Nellie was born, in a way her presence was like that too. She was this massive force. Even though she was a normal-sized child, everything changes when you have a baby.

I: The novel literalizes so many things that I’ve only ever seen in metaphor—I’m thinking of “bird’s eye view”, “head in the clouds”, even the image of a child’s fumbling fingers playing with a dollhouse, sentences like, “After she arrived, the roof of our house came off.” It occupies this strange space between awake and dreaming, between plausible and otherwise, between metaphor and concrete. And it’s kind of a constraint to be writing in a space like that. Or did you think so?

KD: It just came really naturally. It felt like the right way to tell the story. I knew that because I was writing about an actual medical condition, there were things I needed to get right, like how it feels to inhabit a body like that, to hold a pencil, or to walk down stairs when your feet are so huge; and what can be done medically for such a person. But there had to be this playful, magical quality too, so the reader could embrace the idea of Ruth telling the story from above, and watch with her as her life unfolds.

I ended up reading other accounts like that written by people who knew a giant. So that’s how I got to understand what it’s like to be in a body like that, because they’d talk about the size of the hands and the difficulty of walking down stairs.

I: Did you come across any accounts written by giants themselves?

KdH: I came across some interviews with a woman called Sandy Allen who just died recently, actually, and her life story was very useful to me because she was born around the same time as Ruth. But mostly I read accounts by people writing about a brother or an uncle.

I: Which makes sense, actually, considering how much your story is about the family dynamics. Which was part of the reason it reminded me of a Carol Shields book, how you illuminate the ordinary in the same way she does. Your book is rife with allusions to children’s books, and the stories about giants you mentioned, but I wonder if it has any less overt antecedents?

KdH: I tend to stay away from things that feel too familiar to the project I’m working on. So for instance, when I was writing Water Wings, I read a lot about bugs and butterflies, gathering the facts I needed to create my characters’ world. This time it was the fact side of being a giant that I was looking for, and also the details I could mine from fairy-tales. I didn’t want to read novels about close family relationships and the connections between people. Those things needed to come from inside me or be the sparks I notice in my daily life.

But also, books creep in. There’s a book I read with Nellie, Sylvester and the Magic Pebble by William Stieg. It’s about a donkey named Sylvester who has a magic pebble and wishes himself into a rock because a lion is nearby. And he can’t wish his way out again, so he’s gone missing and his donkey parents are terrified and can’t find him anywhere.

It’s a heartbreaking story to read to a child, because every parent has had those terrifying thoughts. So those kinds of books are always in my head, since they explore what I write about as well—family, relationships, and the things that pull us together, as well as the things that threaten to pull us apart.

I: How has reading with your daughter and a focus on children’s books changed you as a reader and as a writer?

KdH: It’s been amazing to either rediscover or find new stories with her. It’s such a moving thing. And blogging about what we read together is wonderful because it means the stories stay with me longer. I have to put my thoughts about them into words, so I appreciate them more. As with a book club. When you sit and discuss a book with others, you get so much more out of it. I: What’s different about reading with kids too is that as an adult, you don’t very often read with people. But as a family, we’ve found ourselves talking about characters in books as a kind of shorthand, connected with ordinary life.

KdH: We’ve just gone through the whole Harry Potter series, which had us all three reading together. We got up in the morning and read at the breakfast table and then as soon as we were all together again, we would read. And in fact, that has stuck with us, because we did it so regularly with those books. The first thing Nellie says when she gets up is, “Don’t forget the book, Mom!”

I: Something else that interests me, because you talk about things creeping into books, is that I found that in your book, the outside world didn’t appear to creep in so often. There were a couple of references to songs on the radio, but we never know the song. The one exception to this is when Iris says that “women have finally had enough and they’re beginning to fight back,” and I guess this is around 1960. But otherwise, we don’t get a sense of the popular culture, and I wondered if that was a deliberate omission and what role did it play?

KdH: I wanted to keep specific reference pulls you out of that, and makes you flip to your own experience.

I: And also makes you measure the plausibility of what’s going on.

KdH: It pulls the reader up off the page, I think. It can be very effective, but in this story, I felt their world needed to be contained, closed off like the parents were as people, and that certain things needed to be blurred.

I: Which is unusual with writers writing about that time because the popular culture is such an easy reference point.

KdH: Yes. But to be honest I’m usually put off by that as a reader.

I: But there was one way the world did creep in. I reread this book around Remembrance Day, and what I noticed that I hadn’t the first time is that it’s such a war novel. It’s a domestic novel, so much about motherhood, but war is always in the background. And one of Elpeth’s aunts makes the point that “the world needs war”. Did your novel need war as well?

I: But there was one way the world did creep in. I reread this book around Remembrance Day, and what I noticed that I hadn’t the first time is that it’s such a war novel. It’s a domestic novel, so much about motherhood, but war is always in the background. And one of Elpeth’s aunts makes the point that “the world needs war”. Did your novel need war as well?

KdH: I think so, though that happened organically. Before this book, I had been writing The Occupied Garden with my sister so we were steeped in war research for a long time. It took me ages to move on to a new project because the work on that book had affected me so deeply. And when I finally did, I made Ruth’s mom an English warbride and her father a soldier, because it fit with the era I had chosen. At the time, it wasn’t something I thought about a lot. Then as the story progressed and I began to focus on making Ruth powerful and not a victim, I wanted to underscore the fact that James and Elspeth had brought their own baggage into their relationship from separate places. The problems didn’t all come from Ruth and the difficulty of having a misfit child. The more James and Elspeth fail to talk about their pasts and how the war affected them, the greater the distance grows between them. I love that point in the book where James is trying to decide whether or not to tell Elspeth about his affair with Iris. He absolutely wants to do the right thing, and he decides that his confession needs to be about his experience on the beach at Dieppe that day rather than about his infidelity. His guilt and despair about that day is what’s always been in the way of them growing closer. And Elspeth has her own confession in that sense too.

I: It’s interesting because the way that so many writers deal with the 1950s and 1960s and their focus on popular culture gives the illusion that the war was really far away by that point. I guess that’s what people were trying to do, to get on with things, but it really was so close, and your book shows that.

KdH: The children who were born in that time were born into this new world, and yet their parents had experienced all that tragedy and didn’t know how to talk about it.

I: But even if they didn’t talk about it, it was there.

KdH: And that was something that I went back and refined so that it was mentioned consistently, because I realized how much the war had really become part of the story.

I: But motherhood is also part of the story. You write about it so brilliantly. In fact, the first piece I ever read by you was “Draw Crying” in The New Quarterly.

KdH: Which was written when Nellie was Harriet’s age.

I: And Harriet wasn’t even born. I was pregnant. I remember being so struck by the piece. And then rereading it again later and realizing I didn’t even get it the first time.

KdH: Because you can’t, right? Until you go through it yourself.

I: Which you write about in And Me Among Them. That excerpt from when the baby was born—the feeding, the crying. It’s such a small part of the novel, just a paragraph. And if I hadn’t have experienced it, I might have just skipped over that part and not realized the weight of it.

KdH: I’ve always written about families. I never set out to create a body of work about families and relationships but I can see how that’s become a constant thread that runs through my work. And in the beginning, I was often taking the child’s point of view. It’s a really natural place for me to go. Even though I can’t really remember a lot of my childhood very clearly, I remember the feeling so I can write about that very effectively and I enjoy doing it.

But what’s newer to me, and what started to come after I had Nellie, was writing about the parents’ point of view in contrast to the  child’s. And I just love that. I think I began to really get it when I was working on The Occupied Garden. The book is about my dad’s family in Holland in WW2, and there’s a point in the story when a bomb landed in my dad’s backyard. He and his brother were outside playing, and they were both very badly wounded—my dad lost his leg and my uncle lost his arm.

child’s. And I just love that. I think I began to really get it when I was working on The Occupied Garden. The book is about my dad’s family in Holland in WW2, and there’s a point in the story when a bomb landed in my dad’s backyard. He and his brother were outside playing, and they were both very badly wounded—my dad lost his leg and my uncle lost his arm.

My grandfather at that time was inside the house and had heard the plane coming. He didn’t have time to run out and he called out the window to them to run, but of course it was too late, and I remember collecting the information for the book and asking my dad about that day, which he’d always downplayed as being no big deal. But this time I asked him, “What do you think it would have felt like for you were in Opa’s place? If you were inside the house and you were the father and you were calling to us and there was a plane coming?” And when he wrote back, he said, “I can’t believe this. I’m sitting here with tears running down my face because I’ve never thought of it that way. I always thought about it from my perspective, never my dad’s.”

And hopefully I would have thought of asking him that question even if I’d never had Nellie, because as a good writer you should be able to imagine all kinds of things without having to live through it—

I: Like how you imagined being 7 feet tall.

KdH: Yeah, but it does sort of open things up once you’re actually living it, once you’re actually being a parent.

I: In a way, all the characters in the novel are set apart from one another, and yet, you have so firmly demonstrated that we’re not so far apart in that you’ve imagined what it’s like to Ruth. You’ve allowed us to understand it. There’s such connection there. I mean, at one point, very briefly, you write from the point of view of a strawberry. You show that we really can cross these lines.

KdH: It’s the connections that are really important to me. The connections between people and the natural world around them are more important to me than the story. The connections are the story. And some people love that and totally get that, and some people want something more straightforward. But I can’t do it any other way. I can only do it my way.

I: At some point in the book, you write about giants needing to be seen to be believed. I think it’s in regards to a book that Elspeth was reading about giants. But you managed to show us Ruth without us having to see her. And you make what she sees even more important than how she looks. Was that always the more interesting question to you?

KdH: Yes. I was interested in how she saw her parents, and people like Suzy and Patrick too, and those descriptions of their dusty, sandy, sun-kissed look; when she looks down at Suzy’s part line with the bug bites. When we do see Ruth, it’s because she’s imagining what Suzy sees, and then she decides that she doesn’t want to spoil the moment of her imagining by seeing herself that way, and she puts the cloth over her mirror. It was more important for me to imagine inhabiting her body than to imagine looking at her. If we saw her too much from the outside, there would be too much distance while reading her story. I wanted to get across her sense of compassion, and empathy, and how she’s so set apart from people but able to understand them in a lovely way, even if they can’t return the gesture.

I: She’s a curiously unreliable narrator though. I love it when she talks about how the story is “her truth”, if not the truth.

KdH: Whenever anybody tells a story, it’s their version. That’s one thing my sister and I learned while working on The Occupied Garden, and interviewing my dad and his siblings about their lives. They would often tell contradicting stories. For instance, in the story about my dad and my uncle being outside when the bomb dropped, one version says that my youngest uncle (who was a baby) was asleep in his crib and didn’t wake up until after it was all over, but he remembers walking through the house and crunching over the broken glass, and coming down and seeing what had happened. It’s just a flicker of a memory and he doesn’t know if it’s real or something he created from the facts he got later. That was one of the most gratifying things about writing nonfiction – figuring out how to incorporate the various versions, and still tell a “true” story.

I: As a writer, does fiction or nonfiction feel like the more natural fit for you?

KdH: Fiction still feels more natural, because it’s more familiar; it’s what I’ve done for so long. But I like the constraints of nonfiction. It’s kind of like cooking, when you say, I can’t go out and buy anything, I have to use what’s here, and I have to make something really delicious. That to me is like nonfiction, and fiction is when you can go out and get whatever you want. It’s up to you, it’s a blank slate.

I: But sometimes a blank slate can be as intimidating as a stocked pantry.

KdH: So true.

I: Who are some of your favourite writers?

KdH: I think I answer this question differently every time it’s asked. Today, Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Carson McCullers come to mind. For children, Roald Dahl and William Steig.

I: What one book would you recommend that your readers read, in addition to your own?

KdH: Do you mean in conjunction with? That would be an interesting question to flip to readers. Two friends told me they read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn after reading my book, and loved the fit. What comes to mind for me is Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. I’m stunned to think she was only 23 when she wrote that book.

I: Who were the writers who made you want to write?

KdH: Hmm. I wanted to write before I could read. Then as an older child, I was as curious about L.M. Montgomery as I was about Anne. I was well into my 20s when I finally figured out what I wanted to write about. I suppose Alice Munro had a hand in that, because she wrote about characters and places that were familiar to me.

I: What are you reading right now?

KdH: Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol.

One thought on “Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Kristen den Hartog”