April 30, 2025

Next Up from Carol Shields

My Carol Shields reread continues to be very rewarding. And especially with her third and fourth (and kind of fifth) novels, which is where her novel writing really began to find its stride. While I enjoyed rereading Small Ceremonies and The Box Garden, especially for the Carol Shields-ness at the core of them, I could discern the effort it took to structure these books, like a kind of scaffolding beneath the surface. But with Shields’ third book, Happenstance, there is nothing but the art itself. Like, the training wheels are off, and there she goes, and this woman knows exactly what she’s doing now. And she’s going to keep on doing it—this is what also amazes me about these early books, the threads and preoccupations that will be picked up through the next two decades of Shields’ literary career.

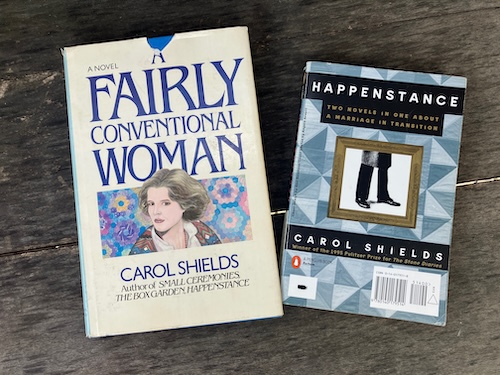

If you buy a copy of Happenstance now, you will likely be purchasing the version of the book which is subtitled, “Two novels in one about a marriage in transition.” One side of it is Jack Bowman’s story, originally published in 1980 as Happenstance, and then flip it over to the over side to read a novel from the perspective of his wife, Brenda, published in 1982 as A Fairly Conventional Woman. As a Shields’ completist, I’m still looking out for an original edition of the former, but I found a first edition of the latter a couple of years ago that I was delighted to read this time. I’ve read both those books before, but don’t remember very much about them. As I’ve said with every Shields’ book I’ve reread so far, I don’t know that they’re written to be properly understood by anyone under the of 30. And it’s curious and interesting to be reading them now in my mid-40s, just a tiny bit older than her protagonists, just a little bit older than Shields was herself when she started to publish her fiction. In some ways, it almost feels like I’m meeting this author I’ve loved since I was young for the very first time.

I imagine that when I read the double version of Happenstance, I read Brenda’s story first, just because women’s stories are usually more interesting to me. But this time, because chronology, I started with Jack, and I actually think it’s a better novel than Brenda’s. I assume Shields wrote it first and Brenda’s later, which might explain it—the material was more fresh for me, she was inventing instead of filling in gaps and picking up threads. It’s also, counter-intuitively for a husband’s story, more concerned with the domestic, as it’s about Jack at home with his children while Brenda is on a trip to Philadelphia, and domestic details are always most interesting to me. All of my favourite books are about people at home.

When I interviewed the author Jenny Haysom about Carol Shields on my podcast last fall, I’d remarked that her novel Swann was something of a departure for her, being more concerned with academia than the domestic, but my rereading has proved that I was wrong wrong wrong. All Shields’ protagonists so far have been academic wives with connections to academia themselves—Charleen in The Box Garden ekes out a living editing a botanical journal affiliated with the academic institute her ex-husband was part of; her sister Judith, in Small Ceremonies, is a biography married to a university professor; and now Jack Bowman works as an administrator for “The Great Lakes Research Institute,” not an academic himself, just with an undergraduate degree, though he has been struggling to finish his book about Indigenous trading practices for years. (He’d met his wife, Brenda, when she’d been working at the Institute doing typing and filing, just out of secretarial school.)

It’s funny because I remember, when Larry’s Party was published in 1997, that there had been conversation about Shields turning her attention to the details of masculinity after The Stone Diaries, but Happenstance makes clear that the details of masculinity had been her concern for a long time. (There is also a character in it called Larry.) And such details also have not changed substantially in the 45 years since Happenstance was published. There is a lot of talk these days about manhood, and men’s relationships, and male loneliness, and Happenstance taps right into all of this. Every Friday, Jack Bowman has lunch with his friend Bernie (his one good friend, Bernie; “his one friend, Bernie?;”There must be a measure of failure, Jack supposed, in the admission that he had gone this far in his life, forty-three years, and achieved only one friendship”), an arrangement going back twenty years, the two of them choosing an all-encompassing topic (this year it’s “history”) and spending their time getting to the bottom of it.

Happenstance is a novel about ideas, about history, about time, about beginnings and endings. Its grasp of its current moment—Russian dissidents and Middle East ceasefires—reads very close to our own. As with Shields’ first two books (and everything she ever wrote?), it’s about the limits to what spouses can know and understand about each other. Also, like everything Shields ever publishes, it’s about what gets to considered important, entered into written record. (Which will bring us to Brenda’s story, but just a moment…)

The one part of this novel that is curious and possibly dated is a story line in which Jack’s eldest son seems to have partaken in a fast, echoing political hunger strikers who are currently in the news. It recalls the daughter in Shields’ last novel, Unless, who takes up residence on a Toronto street corner holding a cardboard sign that says, “Goodness.” This is unfathomable and heartbreaking to her parents, while Jack, in Happenstance, isn’t ruffled by it. He ends up talking to a doctor who tells him that Rob can live without food for a while, he’ll be fine. And then Rob’s younger sister is similarly inspired, and Jack decides that this is good news, because Laurie’s a bit fat anyway, and maybe this will finally be the end of that.

A weird note for sure, and the one on which A Fairly Conventional Woman begins. It’s the same Friday morning on which Jack’s story starts, and Brenda is making breakfast for her husband and children, but she will eat nothing herself. “She is watching her weight, not dieting, just watching. Maintaining.” And then a line about how she’s watching Laurie too, whose jeans no longer fit. Will Brenda too be relieved that their chubby daughter has taken up fasting? Brenda is slim, we know, although (and note that connections between these two ideas are never explored) her mother had been a size 22, and made all her own clothes. All of this making me think about The Stone Diaries, which begins with Daisy’s magnificently fat mother, and clearly fatness too (and maintenance!) had been a preoccupation for Shields, though ideas around bodies and fatness have changed so much since the 1990s, I can’t imagine how those parts of The Stone Diaries will read when I get to it. (Though I am sure that not so much has changed that there won’t be parents out there somewhere relieved that their fat daughters have taken up fasting…)

Anyway, Brenda—a daughter, whose mother sent her to secretarial school, where she’d get the job where she’d meet the man who’d make her a wife—has lately taking up quilting, and it turns out she’s got a talent for it, and she’s invited to appear at a crafts convention where her work will be displayed. Finally, a something of her own, even though it’s a craft, instead of art—and the relegation of the former is made clear when the crafters are made to play second tier to a convention of metallurgists. One of the most fascinating parts of the book are chapters entirely in dialogue by Brenda’s peers at the convention. There’s also a wonderful scene where she buys a raincoat that’s far too expensive, but that she covets, and it reminds me of that scene in Unless (which also appears in an earlier short story) where a character buys a scarf, how a thing can satisfy. (Jack Bowman has doubts about thinginess in Happenstance, however. It’s what makes him suspicious of Brenda’s pursuits. He fancies himself as a man of ideas, elevated above mere objects.) AFCW is about women wanting, or how they don’t want often enough, their desires so often subservient to the needs and desires of others. The reader realizes that Jack Bowman is really wrong about his beloved wife’s inner life.

“What [Jack] didn’t seem to grasp (as Brenda did) was that history was no more than a chain of stories, the stories that happened to everyone and that, in time, came to form the patterns of entire lives, her own included.”