October 16, 2020

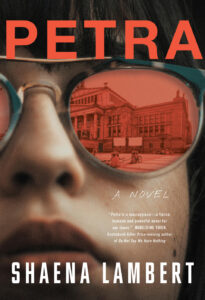

Petra, by Shaena Lambert

I keep imagining the opportunity to interview Shaena Lambert, and the inevitable question: “So why HAVE you chosen to tell the story of Petra Kelly, German Activist and leading force in the creation of The Green Party in the 1980s?” Though I think I already know the answer, and it’s mainly to do with the expansive possibilities of fiction, and how it can shine a light into dark corners that no archive could hope to illuminate. The limits of nonfiction too for a figure whose mythology was almost as important as the facts of her character. And yet that forty years after her fame and three decades after her death that she’s become an unknown, another woman cast aside under the pounding waves of history. So what does it mean then for me to be encountering Petra Kelly for the first time through Lambert’s fictional lens as I have done while reading her novel Petra? It’s destabilizing, a fictional biography, though perhaps in a way that Petra Kelly herself might have appreciated. Or so I can speculate…

While Petra herself was real, all the other characters in the book are invented, or created as composites of actual figures. The story told from the point of view of a Manfred Schwartz, once Petra’s lover, and then her colleague in government as the Greens are elected to office in 1983 on a rising tide of popularity. Manfred never really gets over Petra, but then Lambert’s Petra is the type you don’t. A German who grew up in America in the 1960s and brings that same idealism to the divided Germany in what would turn out to be the last days of the Cold War—but nobody knew that then. Idealistic, uncompromising, seeing the world and its issues as interconnected as her Marxist colleagues never would.

Defying expectation at every turn, Kelly falls in love with an ex-NATO General, a love story with a sorry end. Which also might be part of the reason why Lambert imagines up the figure of Kelly’s General lover from scratch in her novel, for the unfathomability of his actions. Fiction permitting the author more latitude for the fathoming, imagining this figure who’d grown up in Nazi German, fought for the Germans in World War Two, the atrocities that he would have been party to, and how a person lives with that.

The novel takes the form of a historical record created by Manfred, who is still under Petra’s spell after all these years, and is trying to make sense of what happened between them and of her character in general. A proxy for the author herself, I suppose, and the answer the question I was pondering at the beginning of this review comes with a line near the end of the book, delivered by Manfred’s wife: “Maybe you simply can’t make sense of it all…I mean, maybe it—the past—doesn’t take the form of a thesis.” Which is where the art comes in, the role of literature, to make a sense out of something that doesn’t make sense at all.

By the end of the book, Petra has become a full-fledged spy novel, as we learn who among the Greens had been acting as Soviet agents, this information offering some illumination to Manfred about what had gone on decades before. Petra herself, however, remains somewhat in the shadows, the reader feeling the same frustration experienced by Manfred at how elusive her true nature remains, at how many of her secrets would die with her.

But that she is known through this book, if not actually understood, doesn’t lessen the novel’s impact, and in fact makes it all the more engaging, and in accordance with what actually happens in the world.

I’m just reading this now and loving it. Surprised it didn’t make any of the award lists…or did it? (I may have been in a covid coma.) Wonderful review, Kerry.