November 7, 2017

Euclid’s Orchard, by Theresa Kishkan

One of my greatest claims to fame was that I once tied for second place in an essay contest with Susan Olding—whose collection is the wondrous Pathologies: A Life in Essays—and that the first place spot went to the magnificent Theresa Kishkan, who would soon after publish Mnemonic: A Book of Trees. In terms of literature, I don’t know that I’ve ever been in finer company, and I don’t think I properly appreciated this in the moment. Seven years later, I look back and can’t believe that really happened, but I am glad it did—mostly for how it brought me to these authors’ work.

One of my greatest claims to fame was that I once tied for second place in an essay contest with Susan Olding—whose collection is the wondrous Pathologies: A Life in Essays—and that the first place spot went to the magnificent Theresa Kishkan, who would soon after publish Mnemonic: A Book of Trees. In terms of literature, I don’t know that I’ve ever been in finer company, and I don’t think I properly appreciated this in the moment. Seven years later, I look back and can’t believe that really happened, but I am glad it did—mostly for how it brought me to these authors’ work.

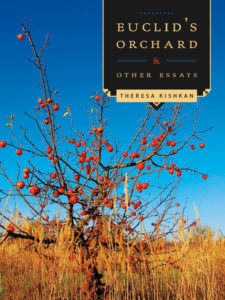

In the years since then, Kishkan has published two novellas, and now a new essay collection, Euclid’s Orchard, which I read avidly over a couple of days last week. It’s a book I’d been looking forward to for a long time and whose genesis I knew a lot about and had kind of born witness to as an avid reader of Theresa Kishkan’s blog. Which is also how I knew that these essays, while they explored many of Kishkan’s usual preoccupations, had been written during a particularly trying time in her life, when she was awaiting a scary medical diagnosis, confronting the weight of her history (so much of it left unknown with her parents gone), and contemplating the wonders of her own children coming up in the world, and becoming a grandmother.

The title essay comes at the end of the collection, referring to her son’s proclivity for mathematics, which came as a surprise to both his parents. She writes of trying to understand the codes and languages of her mathematical son’s mind, and of trying to map such understanding onto her own experiences through quilting. But she is also writing about fruit, and grafting, and the orchard she and her husband planted when they arrived at the place that would become their home, and orchard that would be abandoned for reasons the essay delineates. Which is to say that the fruits they would harvest weren’t the fruits that they were planning on—and isn’t it always the way? There’s not a formula for that. Nor for keeping out the coyotes and the bears either. Kishkan is writing about patterns, and functionality, and parenthood, pollination, and Fibonacci numbers, and coyotes singing:

They were our names, our bodies under the heavens, all of us singing together in different voices to tell the story of our orchard, our time here, in this place we have inhabited since—for John and me—1981, and the only way to shape the story is through connotation, not ordinary discourse, though I praise the literal, the specific, but by reaching up into the starlight to parse what lies beyond it.

Reaching up into starlight (figuratively speaking) is also the only way left to search for answers to the gaps in Kishkan’s parents’ histories, particularly as historical documentation has proven elusive and misleading. In two essays, she tries to make sense of these gaps and the documents, as she searches for her mother’s birth parents—her mother had been born to an unwed mother and raised as a foster child—and as she explores the history of her father’s family, immigrants from what is now the Czech Republic who become homesteaders near Drumheller, AB, although some sleuthing reveals her grandparents had been squatters whose petitions to own the lands they lived on had never been successful. And what do they mean, all these pieces and gaps in her history. As Kishkan writes, “the only way to shape the story is through connotation,” and Kishkan does this masterfully.

In the other pieces, she writes directly to her remote father who always seems disappointed in his sons, who had never properly regarded his daughter. On what to do with a fifty-year-old bottle of her mother’s perfume. She writes about the landscapes of her childhood, places firmly etched on the map of her mind. About trees and flowers, cuttings the history and stories of gardens—and this book is a nice complementary read to Helen Humphreys’s new book, The Ghost Orchard, which I read not long before it. Euclid’s Orchard is a collection of fascinations and astonishments, of the world as it is and was and is ever becoming.