February 5, 2016

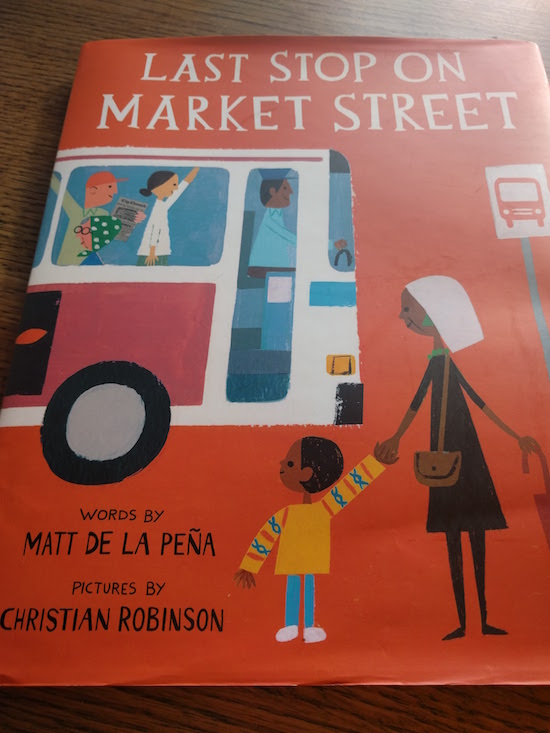

Last Stop on Market Street, by Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately thinking about the nature of an imperfect world, about the gifts inherent in that kind of reality. (The only kind of reality.) That accepting the imperfections and imperfectability of the world is not about giving up hope of making things better, but instead the reason why we mustn’t stop trying—where would we be if we did? And how other people keep us in check—even the assholes. Well-being lies not about improving the assholes, obliterating assholedom, but instead learning to live among them. Accepting too that everybody is someone else’s asshole sometime. It’s all a negotiation, this business of daily life in the world. Even negotiating with those people who will never understand that.

I read an article last weekend about a teacher remarking on her high-needs students: “There are a lot of kids here who keep life interesting.” I’m aspiring to maintain such a perspective on my fellow humans, the challenging ones.

A gift of living in the city and especially raising my children here is that the world’s imperfections are always close at hand. Garbage in the gutters, mentally ill people shouting obscenities in the streets, mentally sound people shouting obscenities in the streets, someone threw up on the sidewalk, drivers nearly bowling us over turning right on red lights, ugly graffiti sprayed on beautiful murals, and people who vape. Here is the world…and yet we love it anyway. Perhaps even more so. Because there’s also bees alighting on flowers, little kids holding their parents’ hands, squirrels eating sandwiches, cherry blossom springtimes, the wonder of an airplane soaring overhead, and music, and finger paint, and dancing to “Trouble” by Taylor Swift. It’s the same reasons we take to read Grimms’ fairy tales at their gruesomest: because here is the world…and yet.

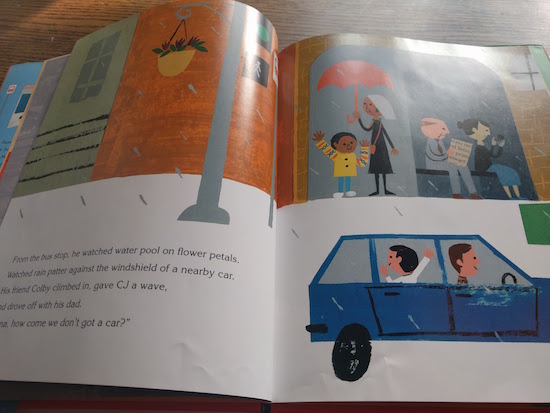

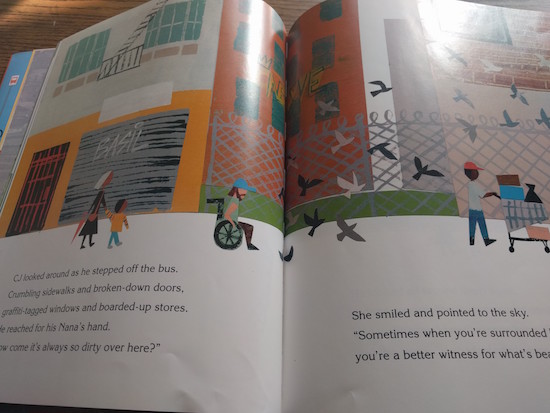

The city in Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s Newbery Award-winning Last Stop on Market Street is San Francisco which, by virtue of its density, is a city of contrasts. We see this as CJ and his Nana board the bus on Sunday after church and make their way across town for a weekly appointment. CJ wonders why they have to go. He wonders why they can’t travel by car, like their friends who passed while they were waiting at the bus stop. But his Nana reminds him of the advantages of riding “a bus that breathes fire” (there is a dragon on the advertisement on the bus’s side), and of the people they’ll meet, the stories CJ will encounter on his way.

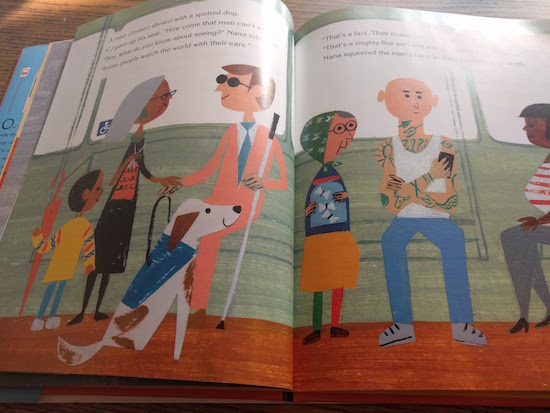

She’s proven right too, CJ’s Nana, knitting as they go, making friends with the man with the seeing-eye dog, convincing the man with guitar to break out in song—to which CJ closes his eyes and launches into a reverie, all butterflies and rhythm and moonlight. When the song ends, CJ tosses a coin into the man’s hat and suddenly they’re at their destination: “Last stop on Market Street!”

CJ is still not sure as he steps off the bus, taking his Nana’s hand. It’s a rough neighbourhood with boarded up shops and graffiti. The only birds are pigeons. His Nana points to the sky though: “Sometimes when you’re surrounded by dirt, CJ, you’re a better witness for what’s beautiful.” And in the following spread we see a bigger picture, a rainbow overhead. “He looked all around them again,/ at the bus rounding the corner out of sight/ and the broken streetlamps still lit up bright/ and the stray-cat shadows moving across the wall.”

The subtle rhyme of de la Peña’s prose gives the story a kind of music, rhythm and cadence. The journey culminates with CJ and his nana’s arrival at the soup kitchen where they work every week serving lunch to the people of the neighbourhood. People who are people in their own right: Esther with her new hat, and the Sunglass Man. And CJ tells his grandmother that he’s glad they came.

The story concludes with CJ and his nana back waiting for the bus, with caged spindly trees and overflowing litter bins, but the beauty’s there: we see it now. Perhaps it’s been there all along.