March 4, 2025

One Day Everyone Will Have Been Against This, by Omar El Akkad

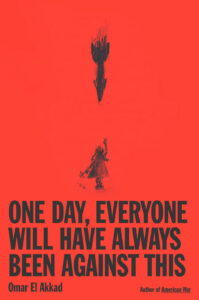

“It is very important to do the right thing, eventually,” writes Omar El Akkad near the end of his new book, One Day Everybody Will Always Have Been Against This, a book which, if/when I post an image of its cover on social media, will make some people angry and disappointed with me. “Eventually” the word on which El Akkad’s sentence hinges, tying back to his title, which comes from a tweet he posted on October 25, 2023, three weeks into Israel’s bombardment of Gaza.

Two weeks before that, I’d reposted an Instagram story about an Israeli rocket hitting the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital, and then took it down after doubt was cast about the rocket’s origins. It is very important to do the right thing right now, I thought, to be cautious and responsible, verifying facts, not to spread misinformation. I took down the post. (In a January 3, 2025 release from the United Nations, after Israel’s December 27 attach on the last functioning hospital on North Gaza, a medical worker reports that “that wearing scrubs and white coats is like wearing a target on their backs.” At that date, the WHO had verified 654 attacks on healthcare facilities in Gaza.)

At a certain point, I pretty much stopped reposting stories about Gaza. Which is not silence, or violence. It is very important to do the right thing, so I must tell you that I continued to write about it in my own words, on my blog and in social media posts, but I was wary of the reposts, of just what I was doing with that project. Who was I talking to? Was it the people in my own community who are stranding up for Palestinian freedom, needing them to know that I too was on the right side? Was it those in my circles who put up Israeli flags on their accounts on October 7, wishing I could follow up and ask them how they felt about that? Or those people I love who fly no flags at all but whose relationship to Israel is ambivalent, complicated?

There really are some parts of this story which are allowed to be complicated. And one of these is two sides insisting on their moral clarity. Sharpie debates scrawled on utility poles around my neighbourhood and all over the garbage can at the subway entrance. Dueling sound systems turned up to full blast. Members of my community being drawn into a right-wing media-sphere full of outright lies and fear-mongering. Rifts in the Canadian literary community that have hurt many quiet people deeply, whether I think those feelings justified or not. And yes, the endless focus (locally at least) on people’s feelings while bodies are being blown apart, the trouble of feelings being the focal point we keep returning to. That some lives get to be mourned and others collateral damage. So much noise.

But in his new book, El Akkad, who was born in Egypt, grew up in Qatar and Canada, and was awarded the 2021 Scotiabank Giller Prize for his novel What Strange Paradise, cuts through all of it to create something most essential, to show the hypocrisy at the core of Western Liberalism as the world does nothing while tens of thousands of Gazans are brutalized, murdered. He writes, “There exists no remotely plausible explanation for a moral worldview in which what a protester might hypothetically do to a hospital [in Toronto] deserves the strongest condemnation, while what a military does—has done—to multiple hospitals deserves none.”

This is not only a failure toward the people of Gaza, it’s a failure to ourselves, to the moral foundation we purport to stand on. El Akkad writes, “Of all the epitaphs that may one day be written on the gravestone of Western liberalism, the most damning is this: Faced off against a nihilistic, endlessly cruel manifestation of conservatism, and someone managed to make it close.”

I don’t think this is a book to be debated, to be countered in the back-and-forth manner of the garbage can sharpie debates (which, I will tell you, have failed to yet add an original element to the conversation or change anybody’s mind). This is a deeply thoughtful and considered book that needs to be understood more than it needs to be agreed with or dismissed altogether. It’s the story of El Akkad’s falling out of the love with Empire, with the Western project that so enticed him as a young person growing up in the Middle East where freedom was curtailed and corruption reigned, a promise of something better, but which has again and again failed to live up to that promise.

He is done with it. He writes, “Everywhere there is a great rage simmering, boiling over, and everything feels like an argument. But there are no arguments to be had anymore.”