May 14, 2024

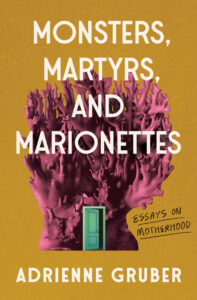

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes, by Adrienne Gruber

As I noted in the introduction to my Bookspo conversation with Adrienne Gruber, I’m not as preoccupied with notions of motherhood these days, or with essays about of motherhood, certainly not as much as I was back in the day when I was publishing my own anthology of essays about motherhood, when I was positively obsessed, and felt like I was working out pressing and essential existential questions with this obsession. The most surprising and disappointing revelation of that experience (along with many others that weren’t disappointing at all) being that motherhood is niche, never mind that everybody everywhere was born to a mother once upon time. But considerations about motherhood themselves are not as fascinated and universal as I’d supposed they’d be back when I was young, starry-eyed, naive and about to publish my first book. (Goodreads reviews for my most recent novel include comments from readers who were disappointed that motherhood factored so strongly into my book, and therefore they found themselves unable to relate to the story.) I think too about what older writers must have thought when I was in the heart of “discovering motherhood” era. And I’m not helping the cause by having now considered motherhood discovered and conquered, because soon it will be a decade since I last changed a diaper. But now Gruber’s essay collection Monsters, Martyrs & Marionettes has gone and got me right back into the thick of it. It’s tapped a nerve. “Pouring off of every page like it was written in my soul.”

There is an essay in this book, “A Route That Does Not Include Your Child,” that is the nonfiction version of the “Hot Cars” chapter of my novel, ASKING FOR A FRIEND. Gruber and I both, I suppose, too attuned to tension, to risk, to possibility (though it’s our job as writers), reading Gene Weingarten’s 2009 article “Fatal Distraction” in the Washington Post with meticulous attention. From the first page of my novel, “Parenthood, Jess observed from her perspective smack dab in the eye of the hurricane, was—if you were lucky— like friendship, a story without end. The alternative too awful to contemplate. But what this also meant, of course, was that it never stopped, there were no breaks from the possibility of something new and worse to worry about around every single corner.”

And this is the neighbourhood that Gruber is exploring in her essays, writing about the various ways that bringing life into the world is tangled with death, dead pigeons on the sidewalk. She writes about her pandemic pregnancy, about the challenges of unruly toddlers and being able to hold a child’s gigantic and ferocious feelings, about being stuck in a two bedroom apartment with small kids due to wildfires that have made the air outside unhealthy to breathe. She’s writing about legacy, about her own struggles with mental illness, and those of her scientist mother, and her grandmother’s cognitive decline. About how essays of motherhood turn out the essays about everything, about the most elemental parts of life itself, milk and sweat, and then a reviewer will turn around and write something like, “This dark comedy is not for the squeamish,” and question who would want to read a book like this.

Anne Enright has called motherhood “the place before stories start”, describing her surprise at finding it was not the sort of journey that one could send dispatches home from. I read Enright’s memoir MAKING BABIES when I was pregnant with my first child, and a decade and a half later I understand what she means. I’d never envisioned how those early days would come to seem like a journey I now cannot imagine having ever taken. “Did we really go through that?” Otherworldly. But this only makes writing down how it was all the more important, because otherwise it would be impossible to remember any of it in that unbroken sleepless blur.