November 30, 2023

The Novel and the Museum

One thing I’ve really wished I’ve been able to spend more time talking about this fall is all the reasons why a museum takes up such prominent real estate in my novel about female friendship, and so when I was was asked to write an author talk for my visit to the Islington Reads book club, I knew exactly what my subject would be. The text of my talk is below and you can also watch it on video above!

When I moved to university in the autumn of 1998, the museum was our entire horizon. Literally. An imposing stone edifice occupying a huge city block that was three tall stories high, the Royal Ontario Museum was directly across the road from our all-girls residence at Victoria College in the University of Toronto, and every night the sun went down behind it, a little earlier than it might have if we’d had a less magnificent neighbour.

All of which sounds very impressive, but I—regretfully, and most unimpressively—have no recollection of ever having gone inside the ROM during those years when I lived so nearby. The closest we came was some Toronto film festival gala there and we’d gone across the street to get a glimpse of Denzel Washington while dressed in our pyjamas. I used to walk through the loading dock on its south side to get to my Literature for Our Time classes three days a week in my first year. I worked at Pizza Hut on Bloor Street on the north side, selling not very fresh slices in the takeout window across the street from what is now the Crystal, but what was then the ROM’s Queen Elizabeth Terrace Galleries, opened just in 1984 and demolished barely twenty years later. The Pizza Hut is gone now too, that entire block transformed. No more Swiss Chalet, Bedford Ballroom, or Country Style Donuts. I used to think that cities were like mountains, solid, stone, unmoveable, but it turns out that they’re as ephemeral as everything.

“What lasts?” is a question that’s one of the preoccupations of ASKING FOR A FRIEND, and also a question whose answers I’ve been wrong about again and again throughout my life, in terms of relationships, fads and fashions. The idea of wearing tapered jeans during the years I lived across the road from the ROM would have appalled me, for example. Or that in my third year at university, I would move into an apartment with a friend I was absolutely besotted with, one of the most magical people I’d ever known, and if you’d told me that there would come a time when I would tell you I hadn’t talked to her in 20 years, I never would have believed you. And all the while, my children are listening to ABBA. How can a person ever tell?

In my fourth and final year of university, I moved into an apartment off campus at Dundas and Bathurst, an apartment you’ve already been introduced to if you’ve read my book: “a place up a narrow flight of stairs above a Chinese herb shop, where there wasn’t an actual hearth—the closest thing was an old electric oven where only two of the stove elements functioned, and the oven handle kept falling off. But the kitchen always felt warm, with the window facing south so the light was usually golden.” I still drive by there twice a week when I’m picking my children up from Girl Guides, and this is how it is when you’ve been living in a city for twenty-five years: am I haunting the places I used to know or are the places haunting me?

It’s a weird thing to raise your children around the same neighbourhoods where you spent your formative—and perhaps most nonsensical—years, to push a stroller along that very same block where I once worked at the Pizza Hut, all brand new condos now. On my way to the museum that was once my horizon, but I have a membership these days, and we head inside, exploring hands-on galleries and dinosaur bones. My children are so familiar with the ROM that it’s almost their horizon too, if not literally. And it was within the bowels of that building where the first spark of ASKING FOR A FRIEND was lit.

Which I’d actually forgotten about, totally. “Every time Jess was pregnant, Clara had been the first to know,” is the first sentence of my novel, and what I’ve been telling everyone since the book came out is how it’s always been the first sentence, the novel beginning with two friends connecting for the very first time altogether serendipitously on a Saturday night in December 1998 in a university residence as snow falls outside and museum across the road is lit up for a gala.

But that isn’t true at all.

Because before I ever wrote that sentence, I’d written about Pompeii, inspired by the “In the Shadow of the Volcano” exhibit I took my kids to at the ROM in the summer of 2015. I think I wrote about the strangeness of taking children to see it, about the eeriness of so much life preserved, and also so much devastation, so much death. (The moral of this part of the story might also be that ASKING FOR A FRIEND was a novel born of my anxiety.)

I don’t remember if Jess and Clara were together in the scene, or how much either of them existed as characters yet, nor do I have any way of finding out what was in those pages—though I remember being fond of them—because somehow or another the whole thing got lost. Not from me pouring tea on my laptop even—I checked and that didn’t happen until the following summer. Most likely I simply saved the file on my desktop and then trashed it by mistake.

“What lasts?” Remember? Luckily, I hadn’t got very far into the document, maybe a couple of thousand words or so. I opened a new file and started over again. (These days, I am a passionate user of Dropbox.)

My novel is fiction, its characters’ stories less rooted in autobiography than anything I’ve ever published before. My previous novel, WAITING FOR A STAR TO FALL, was about a young woman who has a secret affair with a charismatic hotshot politician, and while I’ve never been in that situation, I was definitely able to tap into angsty memories of unrequited love from my own early twenties. With this novel, however, while I’ve been asked if I’m Jess or if I’m Clara, I could probably ask many of you the very same thing. I was definitely not present in that common room on the wintry night—I was probably out accosting poor Denzel in my pyjamas.

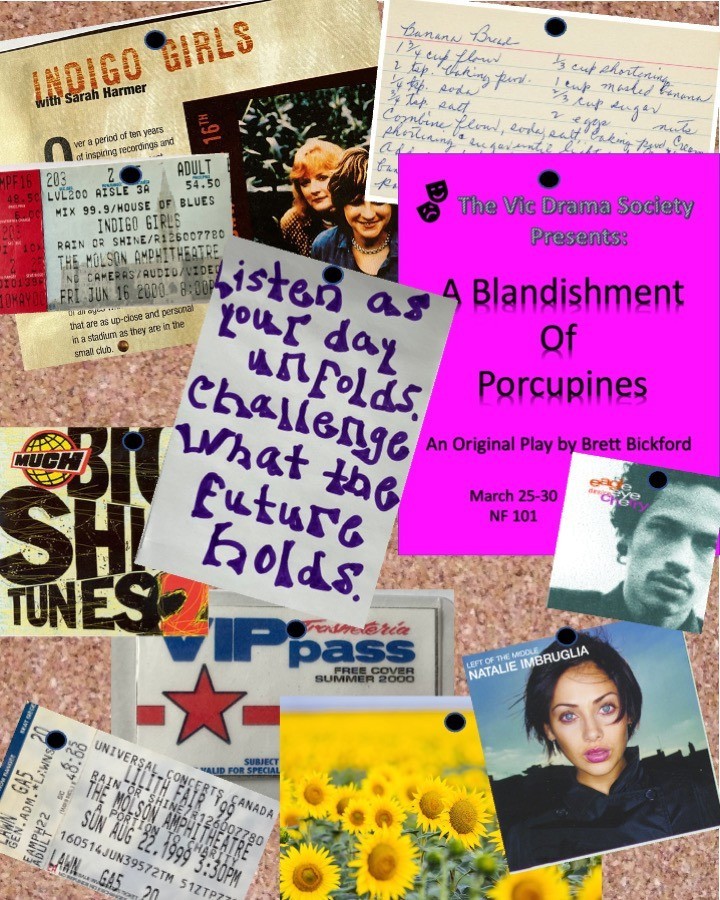

My novel is fiction, but it’s also a kind of museum too, an archive of a particular place and time, my own history preserved in amber, even if I don’t appear as a character. From the book: “Everybody was dressed in the same vintage uniform, flared jeans with soggy hems, second-hand suede and leather jackets, and that smell of wet coats mixed with cigarettes would, for Jess, ever after be a time machine.” I wanted to write about all that, and about being sad all the time and listening to Natalie Imbruglia on repeat, and Big Shiny Tunes 2, and Mmmbop, boys in bucket hats, bad campus theatre, and how subversive it used to feel to haul our mattresses outside, like the whole world was our bedroom.

I wanted to write about what it felt like to be coming into adulthood against the backdrop of 9/11. The way we used to have to go to the library to check our email, and then one day we had internet access at our excruciatingly boring post-grad jobs, and how it brought the world to us. I really did have a job stuffing envelopes at a driving school, and when I showed up on the second day, no one could believe it. I wanted to write about how it felt to be under the sky and convinced you’re the centre of the universe, and I’m not sure if that’s an early-20s thing, or a pre-social media thing before you walked around with a device in your pocket delivering proof that everybody else was out there having fun without you.

In 2011, a decade after we’d lived there, our apartment at Dundas and Bathurst—which was also Jess and Clara’s apartment, the one where the squirrels got in through the ceiling, though in our case it was actually a racoon that lumbered in through a broken window screen, and I don’t remember how we got it out—was literally turned into a museum that was supposed to represent a typical Toronto apartment. I still can’t really believe this happened, and I wasn’t sure I hadn’t made it up entirely until I went back and found the article about it again on BlogTO. At the time, there was a design studio in the first floor shop downstairs, and they’d taken over the apartment upstairs to showcase their work in a home setting—sculptures, furniture, light fixtures. But the ugly linoleum on the floor was the same, and the ancient appliances hadn’t even been replaced. It was weirdest thing, but also bizarrely fitting, that the place where I’d spent some of the most consequential time of my life had been preserved this way, that you could even take a tour—although I only found out about it all after the show had closed and never got to. Which is perhaps for the best, because—as they say—you can’t go home again, and it wouldn’t have been the same. Nothing we ever owned was nice, let alone designed. I would have been looking for the creaky old oak table in the kitchen, a candle stuck in a wine bottle at its centre and wax dripping all down the sides.

So I put it all in my book instead, a book that’s dedicated to the friends who lived with me there, and also to my best friends from high school, all of these women who know things about me that nobody else does or ever will, each of them an archive of the stories of all we’ve shared together. Friendships that have survived, inexplicably, sometimes miraculously, when so many others didn’t. “All Jess ever wanted, in addition to everything, was to know that she and Clara would always be friends.”

What lasts? What survives? These are questions that both my characters investigate in their professional work—Clara does archaeological field work unearthing fragments from ancient hearthstones; Jess is a scholar of folk and fairy tales. Each of them finding in their work what they also are attracted to in each other: Clara, for Jess, is a source of spirit and light; Jess provides Clara with roots and a sense of belonging. And at that particular moment that connects them on that evening in 1998 and in the weeks and months to follow, each is precisely what the other requires, and they become home to each other, which would make for a very best kind of happily-ever-after—except there is really no such thing. In stories, maybe, but not for living things, like city blocks, and human beings, and actual relationships, all of which are as dynamic and ever-changing as nature itself.

What are the odds of any relationship making it, let alone friendships, which lack the cultural rituals, scripts and guidelines with which we navigate romantic and marital relationships? And yet so many friendships do survive, people finding ways to continue to connect over decades, and distance, and tumultuous life changes and other challenges. I still find it mind-blowing that I met my two best friends from high school when we were thirteen years old—an age at which I was wrong about almost everything, but somehow I got that one thing right, that these would be my people. I don’t know if anything has ever been more consequential. And who would I be today without them?

But it wasn’t easy. And that’s also something I wanted to capture in my novel, about how hard it can be to become one’s self in the company of others. To be navigating the particularly shifting ground of one’s twenties and thirties, where every choice seems to have such stakes, and where everybody else’s choices seem to be a reflection—or perhaps, more accurately, a PROJECTION—of your own. Being happy at your best friend’s wedding when you might be brokenhearted. Celebrating your pregnancy when you know that your friend isn’t sure she’s ever going to get to have that baby that she longs for. Of course, we want the best things for our friends, but it can be an aching thing to be toasting their successes when we’re still not sure of the path we’re on ourselves. And even when the paths are parallel—this only makes our friends’ choices seem like more of a reflection of our own, and how do we ever know if we’re doing it right? I think it takes a certain kind of magnanimousness, generosity and strength of character to make through all these life transitions without a little bit of tension, and when I was twenty-five, or thirty, I didn’t possess any of these qualities in abundance. Yet.

It gets easier though—and I don’t remember if anybody ever told me that. That everything wouldn’t always be so fraught, and that I’d come into my own, and so would my friends, and I’d just admire them so much, and be able to respect all the ways in which we’re different and be grateful for the ways in which we’re alike. I’m right in the middle of my 40s now, and I don’t think my friendships have ever been less complicated, which is good because life in general always is, and I have my friends to lean on. Together we celebrate our wins and also our struggles, and I don’t understand the mathematics of it all—how goodness shared is multiplied, and sharing the hard bits makes the load so much lighter.

Which is why I love the ending of the novel, the way I leave Jess and Clara floating, the idea of that ease between them for the first time in a long time, and I like to think that this is their happily ever after. Not that the story is over, but that it will go on like this, that they’ll have found their rhythm, their flow, and that their friendship really will turn out to be one of the great loves of their lives, if not THE one. Each friend finally comfortable with her own self, which makes it that much easier to be comfortable with another, to be at home with each other again in that miraculously way they were when they first found each other.

Which brings us back again to the museum, to 1998, to that building we never went inside (you needed money for that, and we were much too busy watching TLC Daytime), but which was always there, like a great stone giant asleep across the road, as sprawling in geography as it was as a cultural force. As a gatekeeper, an arbiter of whose stories are worth telling, and really I’m talking about the museum as an idea now—and certainly there has been huge progress in the last twenty-five years in terms of thinking about what kind of stories matter, but it’s hardly enough. Because was it just yesterday, or 94 years ago, that Virginia Woolf wrote, in A Room of One’s Own:

“But it is obvious that the values of women differ very often from the values which have been made by the other sex; naturally, this is so. Yet it is the masculine values that prevail. Speaking crudely, football and sport are ‘important’; the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes ‘trivial’. And these values are inevitably transferred from life to fiction. This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room. A scene in a battle-field is more important than a scene in a shop — everywhere and much more subtly the difference of value persists.”

The feelings of women in a drawing room. In a common room, in a kitchen, a stairwell, a bedroom, sitting around tables, lying on beds, putting on the kettle over and over and over again. Women who are talking to each other, and not even about their relationships with men.

In 1998, just like Jess, I had no idea that I was living blocks away from the address where an abortion clinic had been firebombed just six years before. I never knew that my own reproductive freedom was the result of a battle that had been won just a decade before in 1988. Why did it take me so long to learn that it was a Canadian Union of Postal Workers’ strike in 1981 that helped win paid maternity leave across Canada? Where were the museum exhibits about any of this?

“This is an important book.” Which is a subversive thing to say about a novel whose spine is pink, a novel with women wearing bathing suits on the cover, two women who look happy, even. Each with an arm around each other’s shoulder, and the other arm in the air, like they’re belting out the lyrics to a song they know by heart, the way they’ve come to know each other by heart. A story about friends where no one has to die at the end—not yet, at least.

This is an important book because women’s stories matter, women’s lives in relationship to each other matter too, but for too long such stories have been lost to history, absent from the archives, missing from the museum. The feelings of women in a drawing-room—that’s a book I want to read, and this is the book I wanted to write, a novel that captures a sense of a time I never thought of as a particular one as we were living it, but it’s clear in retrospect, which—I’m beginning to realize now—is always the way with history.

Kerry, I so enjoyed reading this. Lovely to reflect on our younger selves and our ever evolving friendships.

Looking forward to reading your book.

Thank you, Susan! xo

You are such a wonderful writer, Kerry.

THANK YOU! xo

Wonderful essay, Kerry! And so true.