October 20, 2021

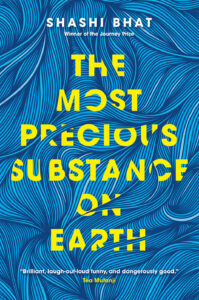

The Most Precious Substance on Earth, by Shashi Bhat

In 2018, when I had the great honour (and pleasure!) of being one of three jurors for the Journey Prize, one of the standout parts of that experience was encountering Shashi Bhat’s writing for the very first time. Although I didn’t know the writing belonged to Bhat herself—the stories were submitted anonymously. All I knew was that “Mute,” which would go on to win the prize, was utterly distinct in terms of its narrative voice, and its clarity, and its point of view. So smart, and wise, and funny, and sad, and I don’t know that I’d ever read anything else quite like it.

And now with The Most Precious Substance on Earth, Bhat’s debut, there’s an entire book of this, and I just loved it, and was just as struck by Bhat’s storytelling as I was the first time I encountered it—her award-winning story “Mute” is actually included in the novel. Which indeed does function as a novel—just as it also stands up an impressive collection of short fiction, as Steven W. Beattie argues compellingly in a recent review—because the entire book is so satisfying and rewarding as a whole.

At first, the appeal was nostalgic, familiar, and I texted my best friends to instruct them to get their hands on this book immediately, because Bhat’s tales of late 1990s high school were just so absolutely transporting to this particular reader (me!) who spent Grades 9 and 10 eating lunch on the dusty wooden floors in the alcove outside the science office of a high school at no longer exists. But it wasn’t only the nostalgia—the stories were so evocative because of the specificity of Shashi Bhat’s eye, which is to the eye/I of her protagonist/narrator Nina, who must seem detached from the outside, and we can understand that she sees everything, even the details she’s still too young and naive to process, such as her inappropriate relationship with English teacher.

It’s all so funny, deadpan, tortured and awful, Nina’s best friend Amy, and her boyfriend, and the way she peels the floors. The absurdity of ordinary experience, which is especially the case in high school, and the novel takes us from Grade 9 to a fateful band trip, and Nina’s coming of age, and the way in which she seems to weigh everything evenly, no judgment. The weight of what her did to her, or what happened to Amy, or what it’s meant to to so often be the only person of colour in spaces that were overwhelmingly white—none of this becomes apparent until much later, and it might be easy for a reader to suppose these experiences don’t actually matter much at all.

But all this is also not to say that Nina is a nonentity, just a simple observer—it’s the specificity of these characters and their experiences that so exalts Bhat’s writing. The baked ziti, and the tomato plants, and that Nina joins Toastmasters, and her parents’ eccentricities—there is nothing general about it, and these are the details that bring these stories to life. They’re also often very funny, Bhat’s prose just as assured and confident. She’s an extraordinary writer, and this is an extraordinarily good book.