May 28, 2020

Terrible and Fine

I can never understand how difficult a moment is until it’s over, which is useful as far as self-preservation mechanisms go—though it might be hard for other people to understand, people who prefer to confront the darkness head on. I imagine those people find my social media posts annoying, everything crumbling, and my insistence on noticing daffodils. But I cannot look at the darkness, instead walking through it in a fog, squinting and imagining that I’m discerning silver linings, and the fog is what’s keeps me going. The fog and the hope, because otherwise I can’t get up off the floor, and it’s doubly convoluted because this crisis, for me and my family, is abstract. Our home is comfortable, we still have our incomes, my children’s needs are met, we’re healthy, and we can afford to stay home and stay safe, meanwhile the weather is glorious, and potato plants are coming up in my garden, and there are wildflowers everywhere—lilacs, peonies, and irises, so much abundance, and so where is the crisis? Whereas if I walked twenty minutes east, I’d encounter homeless encampments, but they’re not on my route. And if I walked by them, would I even see them? How would I make them part of the story I tell?

I cried this morning when the school principal made an appearance on Iris’s class meet-up. Yesterday I scrolled through my Instagram account from the last few months, which is rich with colour and beautiful things, but I knew those images were standing in for sadness and hard feelings (and if you read the captions, this is often the case. I am not entirely delusional). It’s been a terrible few months. It’s also been fine. And how the mind struggles to know both these things at once.

May 27, 2020

Spring Books on the Radio

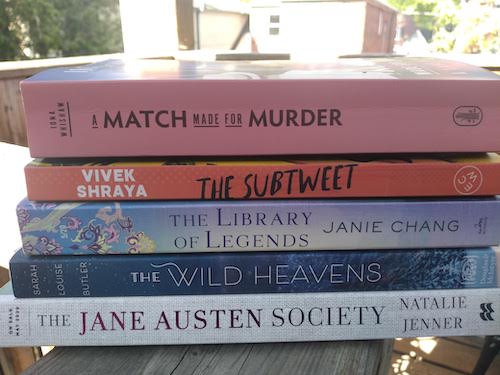

Today I had the pleasure of talking about these gorgeous books today on CBC Ontario Morning: a charming mystery, a breezy but cutting book about friendship, a book that delves into part of Chinese history I’d never heard of before, and the most philosophical book about Bigfoot that you’ll ever read. I ran out of time before I was able to recommend Natalie Jenner’s novel, The Jane Austen Society, which came out yesterday, and if I’d had the chance, I would have told you that it”s a delightful escape from reality, a heartwarming story of how books and community can save us in our darkest days. A lovely hammock read!

May 26, 2020

Gleanings

- It’s time to resist the siren call of pie season and make a galette instead.

- At my desk, in the night, I was thinking about rumours.

- Having the decision made for me by circumstances hasn’t changed everything about how I feel about teaching online, but it has made a lot of those feelings irrelevant.

- What I know about kitchens, is that we make them work, even when they don’t make sense.

- The world is opening up, meaning that we’ll have to see each other again. Get to see each other. My bad.

- And yesterday, I was reminded that all writing starts somewhere, and a sense of wonder–both in the sense of “awe” and in the sense of “curiosity”–is a great starting point.

- when I do get the urge to sew, and when I’ve gotten out all of the things, I binge like a run-on sentence

- Probably I would have melted down by now, but it’s the flowers keeping us going.

- Do you keep a book on your breakfast table and read it in the morning?

- A diary of the mundane and (some of) what we ate.

- what do you think will happen?

- I realize as I do this that I am more interested in the process than the result.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

May 25, 2020

There Are No Good Places to Be During a Pandemic

Are there really no good places to be during a pandemic? During the last three months as I’ve gone nowhere, I’ve certainly had time to reflect on this. And definitely, there are bad places to be during a pandemic—at the source of the outbreak, of course. Or in a care home or group living facility, as the virus spreads through patients and staff (and the systemic failures here are a tragedy. Everything about how these places are funded, staffed and receive oversight has to change). On the streets is a very bad place to be during a pandemic. At work in a hospital is also a bad place to be, particularly when you don’t have access to protective equipment. Twitter is also a very bad place to be during a pandemic, because everyone is as angry and irritable as I’m feeling often these days. So I keep posting lilacs on Instagram instead.

But the idea of a good place to be—I’ve been thinking about this, because for the first time in my life, I have struggled with being in the city, being in the city without a car in particular. Envying people who’ve already escaped to their cottages, people with backyard pools, people with huge houses where everybody has their own room and no parent has to take a Zoom call in their kids’ bottom bunk because there is nowhere else to go. Wishing we had a different kind of life, living off the grid, self-sustainably in the middle of nowhere, perhaps. Would it be easier then? Seeing the appeal of the suburbs, of green lawns for days.

Although I am not complaining. Much. I miss transit though, so strongly, which made the whole city open up wide for us… But our apartment is a comfortable place to be with room for all of us, and the good weather means we throw open the doors and the porch becomes an extra room. We are surrounded by trees. We have a backyard, albeit one that is mainly concrete, but I’ve been hammocking avidly and we’ve bought a small pool that we’ll be setting up as soon as the cover arrives from Home Hardware. We have neighbours that leave gifts on our porch, and friends who leave chalk drawings on the sidewalk, and so many friends’ houses to walk by on our meandering aimless walks. Yesterday we managed to walk down to the lake, which always seems so much farther away than it actually is. (What I would give to visit the beach though!)

We’re luckier than many people, although so many of us can say that. I have a friend who lives in an condo tower, but the lake is at her doorstep. My friends in the suburbs can camp out in their backyards. Friends near lakes can go swimming. Friends in the wilderness are surrounded by the splendours of nature, and those of us in the city have bakeries and sushi joints nearly on our doorsteps, which has certainly made weathering these last few months a more pleasant experience—and I think living in more density has made me more acclimatized and less likely to view every passerby as a potential agent of contagion. My friend who lives in a high rise apartment can walk easily down into the cool of a ravine. Other friends have family nearby. Some have got the low risk of rural communities, but the best hospitals in the country are a ten minute walk from where I live, so it’s a trade-off.

So many of us, no matter where we live, are blessed with the extraordinary kindness of neighbours.

I suppose while there is no good place to be in the midst of a pandemic, the best place to be is where you’re home.

May 21, 2020

The Wild Heavens, by Sarah Louise Butler

I was describing Sarah Louise Butler’s debut novel The Wild Heavens last week as, “Like Contact, but about sasquatches.” A novel set in the BC interior that begins with tracks in the snow, tracks that—in the book’s exquisitely written introduction—persuade a man to reroute his life, from the seminary to pursue a career in science, to explore the mysteries suggested by these outsized man-shaped footprints. Faith vs. science, but the dichotomy turned inside out, and what of mythology? The fact of proof. Maybe it was never really such a dichotomy after all.

The man in the introduction is Aiden Fitzpatrick, through the centre of the story is his granddaughter Sandy who comes to live with him after her mother dies, being raised in their isolated cabin in the wilderness where he continues to search for proof of the creature, one who is never directly named in the book, but they call him “Charlie.” Charlie becoming a projection of each characters’ own fascinations, questions and preoccupations. Sandy grows up in the company of a young boy whose mother has found safety on the remote property, hiding from her son’s abusive father. And in some ways, it’s an idyllic way to live, surrounded by love and so much natural beauty, but there are also questions that have no answers, unspoken longings and so much grief.

The novel takes place over the course of a single day as Sandy—now a widow, a mother in her fifties—sets out to finally discover the truth about the creature after discovering its tracks in the snow after so many years. Interspersed between her risky quest to find it are her recollections of her childhood, growing up with her grandfather, falling in love, becoming a wife and mother, enduring loss and heartache, and the draw of the landscape, that creature who’s ever-elusive. And as ever, it’s less about the finding than the searching, about the wonder instead of answers, about the stories we tell about the mysteries both of ourselves and of the world.

May 21, 2020

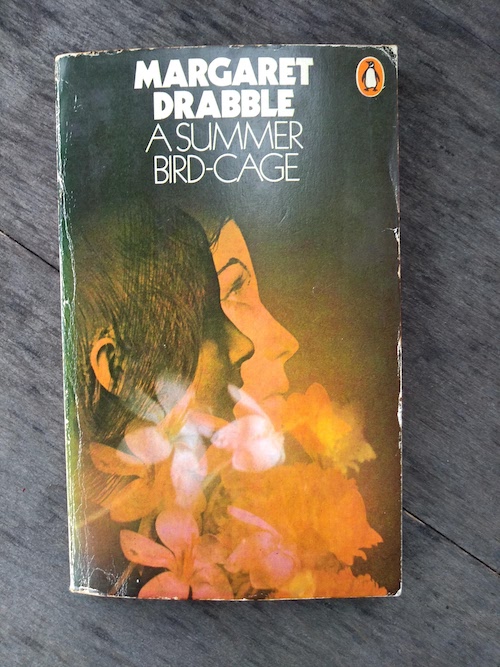

A Summer Birdcage, by Margaret Drabble

I started reading Margaret Drabble in 2004 when I bought The Radiant Way from a used bookstore in Kobe, and I don’t remember why I picked up the book, or if I’d known anything about Margaret Drabble before I did, but I became obsessed with that novel, and the wonderful thing about reading Margaret Drabble in 2004 (even in Japan) was that she had 14 other books I could read after that, many of them readily available in tattered paperback. And so I read them, mostly her 1970s’ novels, which I also loved, but which have blended together, stories of single mothers in London, stories that led directly to The Radiant Way where Drabble’s vision moved from the individual to society, which was pressing in the age of Margaret Thatcher, no matter what Margaret Thatcher thought.

The 1970s novels are fat and the books only got fatter (the final book in The Radiant Way trilogy is huge, and Drabble’s vision has expanded so much more that it’s all about Cambodia now). I was not able to read the more recent books (1990s on…) until I’d returned to Canada, and so most of my later Drabbles are not weirdly stained paperbacks, and I’m a little bit sorry about that.

Her 1960s books, however, compared with the next decade’s, are slim, with those distinctive orange Penguin spines (and many of their covers, oddly, feature Drabble’s own face, which is weird for a novel—but more about that in a moment) and they were never my favourite. Some of those reads that were blessedly short, but I don’t recall enjoying them. They didn’t resonate, and the theory I came up with about that was that they were very fashionable and of their time…which meant they were certainly not timeless.

And so when I decided that I was going to reread all the fiction Margaret Drabble had ever published (what better way to measure out these days, I guess?), her earliest books were what I was most intrigued about, the gap in my Drabble knowledge most need of filling. And, blessedly, they were short, at least.

So I started (naturally) with her first novel, A Summer Bird-Cage, published in 1963, a book whose only detail I could recall was that there was a whole lot about coming down from and going up to Oxford, which I always found confusing. And what I realized upon rereading it again was that a) it still wasn’t really my cup of tea but also b) its use of words I kept having to look up in the dictionary had perhaps kept me from understanding that this book was meant to be relatable.

A young woman, Sarah, just out of school (down from Oxford, natch) who has come back from a sojourn in Paris to be a bridesmaid at her sister’s wedding, her sister who is marrying the celebrated novelist Stephen Halifax, and no one really can understand why. Sarah has a boyfriend herself, but he’s away studying in America, and she meets with friends who’d married just out of school, and it’s all gone a bit wrong, Bohemian husbands expecting wives to cook them dinner on a nonexistent grocery budget. 1963: it was such a long time ago. This was even before the Beatles.

But also this story of being single in the city, weddings and bridesmaids: this is chick-lit, Bridget Jones diary, I wrote in a DM to a friend, and I didn’t mean it in a bad way. But I felt guilty too, because this novel is bending over backward to be exceedingly literary, which is partly why it’s so annoying—it never just out and says what it means, instead gestures vaguely, and I had a hard time discerning the point. Whereas the parts that were supposed to be obscure (whatever was going on between the bride and the best man) was obvious at the outset.

What would young Margaret Drabble think—aged twenty four, and married “since 1960,” it reads, curiously, in her author bio—about the comparison to Helen Fielding?

And here I return to the books with Drabble’s not exactly glamorous face on the cover—I think she was a famous young thing, married to her actor husband, and her personality was very much used to market these books, the same way that women authors complain of today. So we’re really not so apart from Bridget et. al after all…

And now I’m doing it too, reading fiction as biography, when I decide the key to the thing is the line where Sarah confesses, “Beyond anything I’d like to write a funny book. I’d like to write a book like Kingsley Amis, I’d like to write a book like Lucky Jim. I’d give the world to be able to write a book like that.”

But Lucky Jim, if Jim were a woman, would be decidedly chick-lit, slight and commercial, and I’ve always thought that—so my comparison to Bridget feels justified. Moreover the mention of Amis suggests that young Ms. Drabble is writing in the shadow of fashionable male authors, instead of firmly in her own vision, which would explain why this book is just slightly out of focus, doesn’t land perfectly, the way her later books do when Drabble isn’t trying to write like anyone but herself.

And I think this book actually is funny, but the humour doesn’t land right either, because of the way she so particularly captures a moment—between the 1950s and the 1960s, with the advent of feminism—that really was only a moment, before a cultural revolution came along and reshaped the landscape, in a way that Drabble would document in her later novels. So that what she captured here is hard for me to understand so many years after the fact, plus, yes, she is also writing about a very specific social milieu, and maybe she nailed it, but all these years later it’s hard to tell.

May 20, 2020

Finding Our Way

I noticed a chart on social media last week, a list that ranked one’s level of caution and care in terms of exposure to Covid-19, and a few of my friends seemed to find a great deal of appeal in this chart. The idea being that you could determine how you ranked and then find friends with similar rankings to associate with as we slowly expand our social bubbles after two months of quarantine, which makes sense, because you probably don’t want the person you hang out with when all this is over to be Buddy who was over at the Michigan legislature protesting with his machine gun the other week. Not just because Buddy is an asshole, but also because he’s been congregating in large groups without a mask on and likely doesn’t wash his hands.

Of course, there was a level of smugness to it too— I mean, no one who scored “VERY OPEN LEVEL 5” was sharing this chart on Facebook. And I mean no judgment with that either, because I can be as smug as they come, and if you’ve been depriving yourself of human company and good groceries for coming on 70 days now, you have every reason to feel superior to that woman down the street whose kids never stopped having playdates and whose boyfriend sleeps over every Saturday.

But still, it didn’t sit well with me, that list. It was the narrowness, I think—and I would consider possibly because I can’t declare myself a “VERY STRICT 0.” I have not worn masks while walking outdoors, I go shopping more than once a week, I’ve likely been within six feet of somebody while passing on the sidewalk. Although the shops I’ve visited have been small and not crowded, better than grocery stores. But also I live in a unit with shared space with other households. Which doesn’t require riding an elevator and my door knobs are my own, but I am also really not attentive enough at disinfecting doorknobs. Though since people have stopped coming over, I’ve decided not to get worked up over this. But what I mean by all this is what I mean most of the time when writing a blog post, which is that it’s complicated.

Has the pandemic made everyone more annoying, or has it made me irritable, or both, is another complicated question, and the answer is probably yes. (And don’t think I don’t acknowledge that I fall under the category of “everyone” who is more annoying too.)

But I really have struggled these last few months with people’s demands for certainty and clarity in a situation that no one really understands. The week before this all shook down, way back in March we cancelled our trip to England because it was becoming clear that travelling right now would be a really bad idea. Prior to this, I’d been watching government travel advisories and assuming these were gospel, and then had a revelation, which was that just because the government said we could go didn’t necessarily mean that they thought we should. That we live in a country where citizens are free to make their own choices for the most part, and don’t need to be told what to do. I found everyone that first week even extra annoying, because everyone on social media had an opinion about banning flights from certain places, shutting down the borders, etc—when it was clear to me that all this was going to happen, but the government was rolling out measures slowly because they have to. And yet I understand where the complaining people were coming from because there still were people departing on vacation in mid-March, when it was demonstrably clear that this was a terrible idea. But tragically, really (and even literally, sometimes), sometimes freedom of choice means that people are going to make appalling ones.

Or at least ones that are different than yours, ones that you just can’t understand—why that man isn’t wearing a mask, and why that woman brought her toddler to the grocery store, the person standing on the street corner audibly hacking up a lung. For me, much more innocuously, the big one is people who wash their fruits and vegetables in soapy water. I don’t get it—and also, it makes me terribly anxious because I’m just not doing that, and these people doing something different makes me afraid I’ve made bad choices, instead of underlining my virtue and my safety—which is what we all want anyway.

Also: okay. You’re washing your bananas. Great. But why do you have to document it on Instagram?

But my husband has a good point (he is one of the few individuals alive who has NOT been made more annoying by the pandemic) which was that washing fruits and vegetables, and Instagramming them, no less, made those people feel good.

“You know how you liked ordering from the bookstore?” he asked, because this was the week I’d ordered more than fifteen books to be delivered from stores across the city, and he really was bringing this home with an analogy that was so on my level. “Because it made you feel happy, and normal, and like you had some element of control over the world?”

We’re all trying to hard to find our way through this unknown situation. And the people who don’t seem to be trying are trying for the rest of us, and those who are struggling mirror all the ways that I am, and those who seem to know everything only underline just how much I don’t, and I suppose it doesn’t help that my relations with nearly everybody these days are enacted on social media where we are all performing, and sorting our feelings, and showing our best selves and/or our worst ones, and how are the rest of us supposed to tell which is which?

We’re doing it though. By trusting the science, and using our imaginations, we are, no matter how restless and impatient we feel. And that’s the amazing thing, even though nobody really knows what’s what, and it’s never been more apparent what has always been true, which is that we’re all trying to find our way in the dark. But we’re finding it. Day by day.

May 19, 2020

Gleanings

- In one of those ironies you might not even notice if you were swimming three times a week and driving to Edmonton, flying to Ottawa, the flowers have never been lovelier.

- As we speak, my mother is dying.

- What is even better than regular mail you ask? Why, book mail of course!

- What is going to happen to our whole lexicon of (germ-infested) interpersonal body language and gesture?

- What did you think? That a weeded garlic bed would somehow act as a charm against the dark?

- The novel worked for me as a reader, even if, when I sat back to think more about it, it hasn’t proved quite so satisfactory for me as a critic.

- My views are drastically altered, but I must accept it. Gradually, I will. I’m embracing the brightness and the new things out my window.

- In a world that’s on its head, it’s reassuring when we can count on a season to send an evening that is beautiful, and wholly familiar.

- I think we owe it to men to start telling them the truth.

- She wrote about women writing, living in the suburbs, having small children, in a way that gave me hope and acted in some ways as caution.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

May 14, 2020

Rereading Jackson Brodie in the Spring of 2020

“‘Life’s random,’ he said, The best you can do is pick up the pieces.'” —When Will There Be Good News?

There are several ways a reader comes to Kate Atkinson: as the award-winning author of historical novels including Life After Life and A God in Ruins; as author of the Jackson Brodie detective novels, which were made into a celebrated television series; or as the quirky literary superstar who won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award in 1995 for Behind the Scenes at the Museum, an event celebrated with news headlines referring to Atkinson as “an unknown hotel chambermaid.”

The third route was my own path to Kate Atkinson’s work, though I didn’t encounter it for another decade, reading a copy of a library book I’d borrowed from a friend, which seems like the least intimate literary encounter I’ve ever experienced, but it changed everything for me, the unforgettable first line marking Ruby Lennox’s conception: “I exist! I am conceived to the chimes of midnight on the clock on the mantelpiece in the room across the hall…”

I wasn’t fond of detective fiction when I picked Atkinson’s Case Histories, presumably around the same time, but it occurred to me when I did that all literary fiction is about mystery in a sense, and indeed Behind the Scenes at the Museum was, structurally at least, a work of detective fiction, except the sleuth was the reader, because it’s a puzzle of a novel with a solution I didn’t see coming.

But I read Case Histories, because Kate Atkinson was now on my list of fundamental authors, authors whose work I will buy the day of release. Even if I wasn’t as crazy about Jackson Brodie as other readers were, perhaps distrusting of genre—although these books would prove to be my gateway to detective fiction proper, and fifteen years later, I’m absolutely a devotee.

And maybe it was because these books weren’t my favourite, or maybe it was the reason why they weren’t: the plots of the novels didn’t stay with me. Except for the first book, vaguely, the story of the Land sisters and their pile-on of tragedies. When I sat down to reread Case Histories this year in March, it was remarkable that I remembered nothing at all about the story except who had dunnit.

Part of it was that I’m not sure detective fiction necessarily lends itself to rereading for the average reader (and I am also talking about the average work of detective fiction, of which the Jackson Brodie novels, I think, are not). Also because this is a series of novels that have come out over fifteen years—it’s been ten years between Started Early, Took My Dog and the latest, Big Sky. Which I read last June on my 40th birthday, and I remembered nothing of the books that came before. Which is fine—each of these novels stands up fine on their own. But to miss anything of Atkinson’s keen sense of story and detail would be thoroughly a waste, and I thought how much I’d appreciate the chance to reread the Jackson Brodie books from start to finish.

And when the world fell apart in March, and I cycled into despair along with it, finding myself unable to read, the chance appeared, and I took it. Case Histories: An absorbing novel rife with plot, perfect for escaping. But also undeniably dark, brutal, violent, in a way that resonated with the world around me. A book that was an escape, but that was not completely a disconnect either. Why do bad things happen? Why is life so unfair? How do we keep going when people die? How do people survive trauma and tragedy? What kind of life is possible after that?

I was still pretty shattered when I reread Case Histories, during that very bad week I spent unable to eat, barely sleeping, having panic attacks, and finding it exhausting to walk upstairs. But the act of reading, of finding joy and solace again in a book, which is my usual practice, helped me to find my centre again, to find my feet, and feel at home inside myself even at this very strange time.

I don’t know that I properly understand these books’ notion of justice until I read them again in 2020. Jackson Brodie as an outlaw—he used to be a policeman. But the sense that justice proper lives outside the law, which continues to benefit the powerful, which continues to undermine the safety of girls and women. Jackson’s origin story lies in the murder of his older sister, a murder that was was never solved, and it’s a need to right what happened somehow that drives Jackson in these novels, which portray a world, very similar to our own, which is a dangerous case for girls and women.

That murders go unsolved, crimes unavenged. Clues don’t add up, villains get away with it, the banality of so much of this. Reality is a different kind of narrative, is what these books are saying, and yet, somehow, within the confines of a narrative, and there is the possibility of redemption in that. For the world, I mean. The possibility of hope.

One Good Turn takes place two years after Case Histories, Jackson in Edinburgh where his girlfriend Julia has a show at the summer festival. “A Jolly Good Murder Mystery” is the novel’s subtitle, and there is a rollickingness to the novel, whose characters include a writer of middling detective fiction. One Good Turn is self-aware, possibly winking. And its many strands are slightly absurd, but their weaving is masterful, a much richer tapestry than Case Histories. The confident way it all holds together.

And then When Will There Be Good News?, which is a literary masterpiece, I think, the best book of them all, and they’re all extraordinarily good. Featuring Reggie Chase, who appears again in Big Sky—but I didn’t remember her. Unfathomable too, because she’s basically unforgettable. A teenage genius from the wrong side of the tracks, almost no one to guide her. A devastating train crash, and it’s Reggie who saves Jackson’s life, forever in his debt—and doubly, because he writes her a cheque that bounces when his wife disappears with his entire fortune. And we meet Louise Monroe again, the police inspector from the previous book, and this all is a book about trauma, and violence, everyday brutality, domestic violence—and Atkinson even makes it funny, like all the books, which still doesn’t undermine the enormity of the message. Humour is how you make it bearable, I guess, and it helps that life is so absurd.

To reread a series of books so concerned with history is interesting, and the series also shows the changes occurring during the years they were written and take place. I will never forget my first trip to the UK post 2008 economic crash, how different it was, all the holes in the streets where the Woolworths had been—and Started Early, Took My Dog is situated in the wreckage of that moment, another kind of trauma. “The world was going to hell in a handcart…” The sex workers who used to do the job because of poverty, but now it’s because of addiction. Started Early… moves between the 1970s and 2010, and it’s a strange kind of nostalgia. It wasn’t that things were better then, but they were different, that’s all. This is a novel that’s about the fraying of the social fabric, but that’s not necessarily a contemporary story, and might be classic after all. There also have always been bad guys, and some things never change, which is why Jackson Brodie knows as much as as he does—when he’s not walking headlong into disaster.

(This novel is also the way I discovered Betty‘s, and made our first visit to the one in Ilkley in 2011, on the recommendation of Jackson Brodie himself… “If Britain had been run by Betty’s, it would never have succombed to economic Armageddon.”)

And then last week I reread Big Sky, not even a year after the first time, and I knew Reggie Chase this time, now a police inspector herself. And I loved it, just like I loved all of them—its furious, unabashed politics and strong sense of justice. And I loved too the way a few strands in the book that do not quite get tied up, which could suggest that perhaps there are more Jackson Brodie novels to come. A reader can hope…

Or else it’s just that these books, while precise in their composition, are also meant to mimic reality—rough, ragged, and untidy, but sometimes so sublime.

May 12, 2020

Gleanings

- Thrilling (read: meaningful, brave, productive) conversations between friends don’t require mountaintops or war zones—they thrive in deceptively placid settings, where restless hands brush aside crumbs while the worst of life’s torments are explored.

- Though the mulberry is technically invasive, and sometimes I resent the way it’s shaded out part of my garden, I still see the tree as a gift.

- This virus is teaching us a whole new vocabulary. Social distancing. Self isolation. Presumptive. COVID-19. I even had to dictate this new word into the dictionary of the voice recognition software I use to write. (New blog alert! By a BLOG SCHOOL GRAD, no less!)

- While we all remain a little concerned individually that our reading enthusiasm and tempo is not quite what it was (but hey, it’s never been a competition), our aggregate book list is still rich, formidable and gorgeous.

- When the pool re-opens, I’m not sure how I’ll feel.

- What matters even more for me is a cookbook about eating and sharing as much as it is about cooking.

- It’s been ten years since my mother died but I think of her daily.

- You are one great dame and each time I think of you I’m reminded that there is really no higher aspiration for a woman.

- Homemade tater tots, huh. Huh. I would not bother, personally.

- As this shut-in time wears on and wears me down, it helps to imagine doing a little more ‘square haunting’ of my own some day.

- One of the things I’m most grateful for in this life is the innocence, security and endless love of my childhood.

- This is one instance of a more general dilemma which radical political movements have often grappled with: should we choose our terms to reflect the world as it currently is, or the world as we would like it to become?

- You’ll have to write a new Covid edition of your book called The Artist’s Way: Watching The Great Canadian Baking Show Counts as Art when the Alternative is a Mental Breakdown.

- ‘I think I have forgotten what a street fully lit and all the other things that go with peace look like…’

- It felt like hope. The world was showing off and waking up and maybe that was the sign that she would, too.

- If you’re lucky, like me, and live near a forest full of shagbark hickory trees, it’s easy to make this wonderful, velvety, smoky, sweet syrup – a gift from the forest.