March 27, 2019

A To the Lighthouse Memoir

“…one of the wonders of Woolf’s novel is its seemingly endless capacity to meet you whenever you happen to be, as if, while you were off getting married and divorced, it had been quietly shifting its shape on the bookshelf” —Katharine Smyth

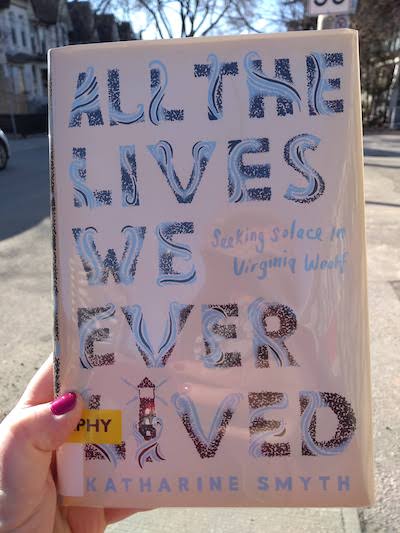

Lost somewhere in the flotsam and jetsam of Instagram is the post (from who? and when?) that prompted me to put Katharine Smyth’s memoir All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf on hold at the library. It might have been the cover that did it, a wonderful retro Hogarthian design, or maybe just the premise itself, a memoir via To the Lighthouse (and you either go in for such things or maybe you don’t—for the record, I was the target audience for Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch Memoirs framed by reading experiences are so up my middlebrow street). To the Lighthouse is a book I’ve returned to again and again since I first read it in a university class 20 years ago—I was rereading it the summer I wrote my first novel, which is part of the reason why my protagonist ends up reading it for her book club. And the other part of the reason why To the Lighthouse turned up in my book is because of the uncanny way that it (like much of Woolf’s oeuvre) ends up seemingly connected to all things, wrapping its way around our own lives like tentacles. It is a book that one only appreciates more upon acquiring some life experience, and then some, a kaleidoscopic novel that contains multitudes: from Katharine Smyth, “To the Lighthouse tells the story of everything.”

I wonder if anyone who loves To the Lighthouse could write a memoir using the book as a framework—but they would probably not do nearly as good a job of it as Katharine Smyth has. Smyth, who studied at Oxford and took classes with Hermione Lee, who knows of what she writes, and whose prose does not read skimpily alongside Woolf’s own. Smyth is a writer with tremendous descriptive powers, a reveller of words and language—she sent me to the dictionary to look up “tenebrous.” And her own story is not a To the Lighthouse redux, but rather she tells the story of her father’s death—and also the story of her parents’ marriage, of her childhood, of her father’s alcoholism and years with cancer, of their waterfront home in Rhode Island—and it maps onto Woolf’s narrative enough to provide glimpses of illumination, just as Woolf’s own biography—her family’s home at St. Ives, the death of her mother, the devastation wrought by the Great War—illuminates her novel.

If it’s true that we tell stories in order to live, I think that we read them for the same reasons, to discover context, evidence, and meaning. After the death of her father, Smyth goes back to Woolf to better understand what happened to her family, to examine their complicated relationship, to bridge a gap between her memories of him and her life without him (ie [Time passes]). Hers would be an interesting story anyway, and she’s a wonderful writer, but it’s all the richer when regarded through Woolf’s literary lens and so is her reader’s connection to it.

This sounds just wonderful. When I was 18, I was given a first edtion of A Writer’s Diary, with a Vanessa Bell cover, and stupidly I lent it to someone who moved away without returning it. Woolf has always been important to me, maybe even more so as I grow older and appreciate what she accomplished, and how, and why. I’ve been reading her essays again and find in them such richness. I read Mrs. Dalloway every year and To the Lighthouse every few years. She’s not always comfortable (and not always kind) but man, there’s wisdom there, and beautiful writing, and a huge troubled soul that is endlessly interesting. She would be a perfect companion to writing a book about one’s own life.