September 13, 2018

Late Breaking, KD Miller

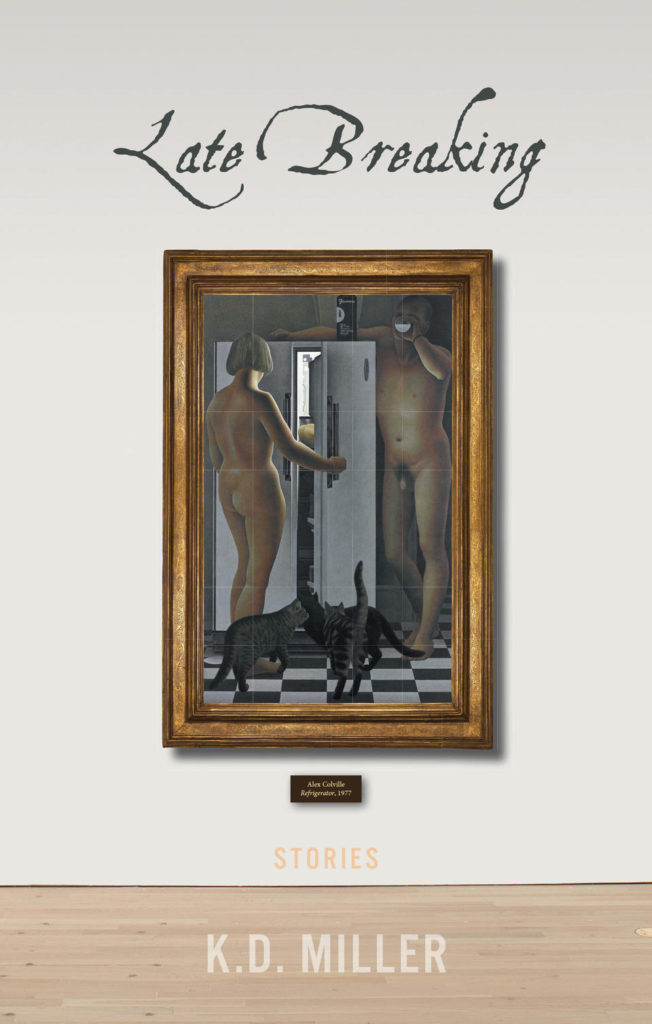

So, if we’re talking about remarkable things, let’s start with the obvious one: the cover. How many other book covers this season feature a naked man drinking milk? I’ll wait. And in the meantime, we can talk about “Refrigerator,” by Alex Colville, which on the advanced copy of K.D. Miller’s Late Breaking that I read was less subtle than it is on the finished version, above. Which meant I felt kind of conspicuous reading it in the dentist’s waiting room the other day, but then I got over it, because the book is so excellent that the penis on the cover quickly ceases to be the point.

And so too does this collection’s conceit, which is that each story is inspired by an Alex Colville painting. Which is not to say that this way of collecting stories into a book is not compelling—absolutely not. It’s an fascinating idea that adds additional texture to Colville’s work, and the stories themselves are similarly absorbing, both ordinary and extraordinary at once, and disturbed by an uncanny strangeness—like the gun on the table, a horse on the train track. Each story is preceded by an image of the painting that inspired it, and the connections between the works are surprising and illuminating both ways.

But this too is eclipsed by something far more central to the text when we talk about the collection: which is that the stories themselves are incredibly good. The first story (inspired by “Kiss With Honda”) is about a widower whose relationship with wife was tainted by a secret she never knew he realized and was never able to explain before he dies, and then he goes to visit her grave, which leads to an act of violence that comes out of nowhere—and suddenly we realize that these stories have teeth, and claws. The second story is about Jill, an older woman whose novel has been shortlisted for an award, and she’s touring with a motley crew of other nominated authors, all the while reflecting on the sex-lives of septuagenarians and the relationship (and heartache) that inspired her work. The third story, “Witness,” takes Colville’s painting “Woman on Ramp” literally—Harriet is the woman on the ramp, and after coming out of the lake and into her cottage, she finds an arm around her neck and something sharp against her back. “Olly Olly Oxen Free” is about the marriage between a woman and her husband, a failed novelist, intersected with story of an older woman in her book club who still carries the pain of a traumatic childhood event. In “Octopus Heart,” a lonely man (who turns out to be the one who broke Jill’s heart in the second story, five years before) feels the first intimate collection of his life with an octopus from the aquarium. In “Higgs Bosun,” a woman (whose son is married to Harriet’s son from a previous story) thinks about the ways she’s tried and failed to hold the world and her family together. In “Lost Lake,” the family from “Olly Olly…” are away at an isolated resort where their daughter seems to be visited by sinister supernatural forces. “Crooked Little House” takes us back to the widower from the first story, and his neighbour (who is the estranged daughter of the octopus man), and their friendship with another man who is trying to make a clean start after twenty-five years in prison. For the murder of a woman who, we realize in the next story, was a friend of Harriet and Jill, all of them meeting one summer long ago—and this story begins with a wonderful scene in a locker-room, older women squeezing into their bathing suits without regard for their naked bodies. “Have we all just given up? Harriet thinks, hanging her suit on a hook in one of the shower stalls and rinsing down. Or is this wisdom?”

These are all rich and absorbing stories on their own, but even richer for how they also inform each other. Eventually I would be making a chart in the back of the book to figure out all the surprising connections, including the final story, about the murdered girl’s mother who was also author of a book about octopuses that preoccupied a character in a previous story. Similar to my friend Rebecca Rosenblum’s work, K.D. Miller’s fiction seems to conjure whole worlds, with characters who seem to walk off the page and who—one has no doubt—continues in their adventures even when their stories are finished. We get glimpses of these people, but they’re like the tip of an iceberg and there’s so much more going on beneath the surface. Which is something you could say about the people in Colville’s paintings too, and about each of these stories themselves, compelling and disturbing, and impossible to look away from, creating the most terrific momentum.

Easily the best painter that Canada has produced .Smart cover design