September 28, 2018

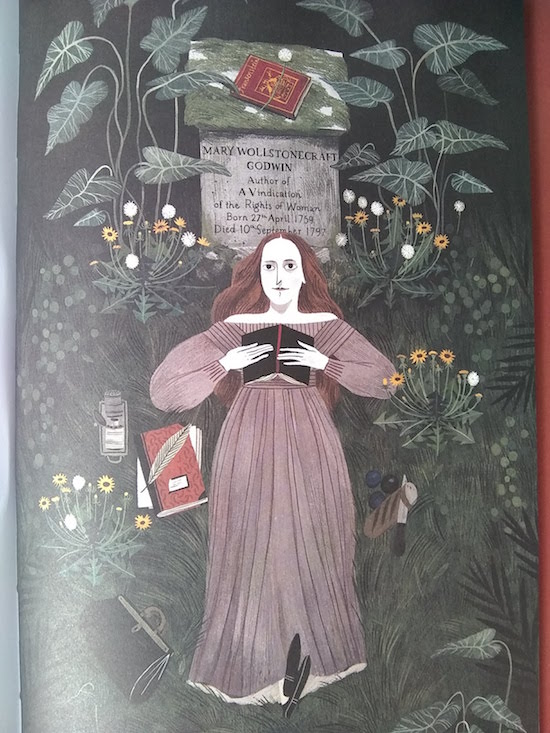

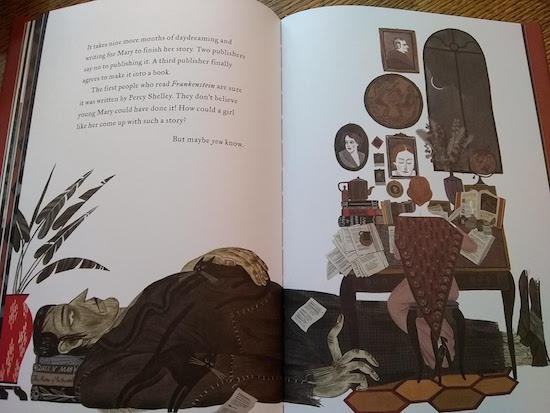

Mary Who Wrote Frankenstein, by Linda Bailey and Julia Sarda

“HOW DOES A STORY BEGIN? Sometimes it begins with a dream…”

I’ve been really looking forward to Mary Who Wrote Frankenstein, by Linda Bailey, illustrated by Julia Sarda, which brings together so many of my favourite things: Sarda’s creepy/gorgeous art—she also illustrated Kyo Maclear’s The Liszts; early feminist history with references with Mary Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft (Shelley’s father, William Godwin, would teach her to read by tracing the letters of her mother’s gravestone; the fantastic story of the creation of the Frankenstein; and also the character of Mary Shelley herself, bookish and rebellious. By the time she is a teenager, Bailey writes, Mary “has become a Big Problem,” and she’s sent to live away from her family in Scotland. “But at sixteen, when she returns to her family, she is still a Big Problem.”

“And what does she do next?” the story continues. “She becomes an even Bigger Problem. She runs away with a brilliant young poet…” In dark and brooding spreads, we see Mary Shelley and her companions travelling through Europe, meeting up with Lord Byron in Switzerland, and that dark and stormy night with the ghost story contest 200 years that has since become the stuff of legends and birthed one of the most famous stories ever told.

Throughout the story and detailed in the illustrations are all the seeds that would culminate in the Frankenstein story, intermingled with an emphasis on tales and dreamy, and steeped in a delightfully creepy aesthetic. Readers discover that powerful stories can come from unlikely places—even an eighteen-year-old girl who wasn’t sure she’d have a story to tell. We see the way that the borders between stories, dreams and life are fuzzy, and how they overlap in places—and the incredible possibilities this offers for what we can make of our lives.

September 27, 2018

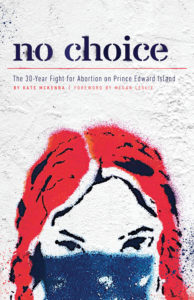

No Choice, by Kate McKenna

I think it’s because it just make sense to take for granted the things that one should take for granted (such as bodily autonomy) that feminist history seems to so often be overwritten. After I had an abortion in 2002, it would take years before I properly understood that I was fortunate to be able to access the procedure in such a straightforward manner. It never even occurred to me that I wouldn’t be able to. I had no idea that just ten years previous, in 1992, an abortion clinic around the corner from where I now live had been firebombed. Such recent violent history—in my own neighbourhood—but I hadn’t been paying attention.

I think it’s because it just make sense to take for granted the things that one should take for granted (such as bodily autonomy) that feminist history seems to so often be overwritten. After I had an abortion in 2002, it would take years before I properly understood that I was fortunate to be able to access the procedure in such a straightforward manner. It never even occurred to me that I wouldn’t be able to. I had no idea that just ten years previous, in 1992, an abortion clinic around the corner from where I now live had been firebombed. Such recent violent history—in my own neighbourhood—but I hadn’t been paying attention.

And nor did I understand that across Canada, even now, access to abortion was varied and even impossible—particularly for women in rural areas and across the Maritimes. In her book No Choice: The 30-Year Fight for Abortion on Prince Edward Island, Kate McKenna explains the power held by the Catholic Church in PEI and how that power enabled pro-choice activists to stack hospital boards by 1986 so that not a single abortion would be performed there for 30 years afterwards. She also shows how the the fight by pro-choice activists was exhausting, marked by setback and after setback. It didn’t help that in such a small and conservative province, people speaking up for the pro-choice cause could find themselves targeted and alienated. (For a long time I thought the history of progressivism was one of triumph. I read a biography of Jane Jacobs two years ago, and recall someone telling me that the real reason Jacobs stands out is that she’s one of the few fighters who ever managed to win.)

For a long time on Prince Edward Island, nobody won. After activism in the 1980s and 1990s, the pro-choice movement on PEI had mostly faded away. Women who found themselves pregnant would have to travel out of province for an abortion, and for many women (particularly those who were vulnerable and/or low-income) this was impossible. Women who returned home after these abortions were unable to access the aftercare they needed, sometimes with dire consequences. McKenna writes about women she knew pooling funds for “abortion insurance.” But in 2011, things started to change. It was a perfect confluence of events that no one could have planned—the rise of social media that allowed women to share and tell their stories; an activist group McKenna and her friends started to counter an annual “right-to-life” event in Charlottetown; enough time having passed for feminists to have forgotten the future was hopeless, I suppose; data from researchers at the University of Prince Edward Island; women who were willing to be public with their abortion stories; a guerrilla campaign of posters featuring the striking image shown on McKenna’s book cover. By 2016, PEI had a new Premier who was willing to consider an alternative to that “status-quo” that so many other politicians had been so comfortable with—McKenna quotes activist Professor Colleen MacQuarrie as being exasperated by this focus on status-quo, “Like it was a good compromise. Women’s health against…people that feel a little uncomfortable with the idea of abortion.”

On March 30, 2016, the PEI government announced that they would create a reproductive health centre in Summerside, PEI, that would offer abortions, among other services. After thirty years of fighting, the women of PEI had won the right to healthcare that millions of other Canadian women had access to. But the story isn’t over—in feminism, it never is. No doubt, the pro-life forces are still at work in PEI, and Anne Kingston has written about their plans to play a major in the 2018 Federal Election. And so that end, it’s smart to know what Canadian women are going to be up against, and to learn that there is value in fighting, that the battle can be won,

September 26, 2018

Spending a Morning at School

“All those beautiful back to school pics are a reminder (to me, anyway) of how deeply vested so many people are in the education system & that it can be political dynamite to mess with it recklessly.” —Shawn Micallef

One reason I like volunteering at my children’s school is because I’m nosy. And when a nosy person commits to spending a few hours administrating a fundraiser from the office—sorting order forms by classes with letters to parents—that person is not simply organizing papers. She is paying attention. And she is welcome to be there paying attention as she shuffles papers, because she’s going to be bringing in a few hundred extra dollars to the school coffers, which are chronically underfunded. Every little bit helps, and teachers and school administrators are expert at stretching those dollars at far as possible, finding value, and making them count. So I’m happy to help, and besides, there are plenty of places for me to work—the Vice Principal’s office? The nurse’s room? Because, of course, there is no money either for Vice Principals and Nurses anymore, and the Secretary relies on volunteer support. Speaking of stretched, and I’ve not even got to Education Assistants (gone the way of the Vice Principal…) or caretaking staff (of which there are a few, but as few as possible due to budget constraints). This is not austerity, but also I can’t remember the last time our provincial government made a major investment in public education. And yet there is something miraculous about the way it all functions anyway, credit for all of which is due to the amazingness of people.

Part of the reason it works is because we expect it to—every morning we drop off our children, those extensions of our hearts, and then we go out into the world to do the things we do, and we take it for granted that our children are safe and cared for, that they’re learning, that they’re even happy. And for many of our children, this is mostly true, at least on the good days. And when all our children went back to school in September I was struck by the reality that plenty of parents who were taking our schools for granted as much as I did had voted to elect a provincial government in June with no respect for teachers and a disdain for public education in general. (Our new Minister of Education’s background is managing a goat cooperative, and she has still given no media interviews about her portfolio which has been controversial since her government elected to dismiss an updated sex-ed curriculum [against the advice of experts] and cancel a curriculum rewrite that would have boosted Indigenous content. Her deputy is a twenty-one-year-old who was homeschooled and whose limited worldview is informed by his extreme religious views)

And how could they do that, I wondered. How could they send their children into the care of people whose profession their electoral votes had so undermined?

“Because they know teachers will still do the best possible job with their children,” answered my friend Dorothy Palmer when I posed that question on Facebook a few weeks ago, and Dorothy, a retired teacher would know. But I know too, or at least I’m reminded after the time I spent this week sorting papers in the office, paying attention. To the tiny people from kindergarten who had the huge responsibility of bringing the attendance down to the office this morning, in pairs of course. To the older girl who’d hurt her knee in gym and came to get ice, and also all the other people who came to get ice—after falling on the playground, getting hit by a soccer ball, going too wild on the monkey bars. Ice is the most tremendous tool, and it makes so many things okay again. Which the teachers know, the teachers who come into the office to check their mailboxes, who greet their colleagues jovially and say hi to students they haven’t seen since last year and remark on who has grown tall over the summer.

There was a little boy in the office this morning and it was his first day of school ever, and he was terrified, unhappy to be there. His dad was in the office filling out paperwork, but could hear his son crying down the hall where the boy was being comforted by an ECE. Over the course of my time in the office this morning, this small boy and his father were greeted by teachers, and welcomed to the school, and the kindergarten teacher came to ask if he wanted to come along to gym. When I finally left awhile later, the boy had joined his new class, no one was crying, and the relief on his father’s face in the hall reminded me of how good I felt when my eldest daughter finally stopped crying every morning for the first month of Junior Kindergarten, that maybe we could find a place here.

At our school, the Principal knows everybody’s name, and when it’s your birthday they put your name on the announcements and you get to come down to the office and receive a brand new pencil. The school Secretary is mostly magical and plays her guitar for the kindergarten classes. At our school, psychologists and speech therapists and other specialists visit to give support to kids who need it. My daughter has had occupational therapy help with handwriting, and speech therapy. When her Grade 3 teacher had concerns about her speech, she went back and talked to her teachers from the year before. At our school, our amazing music teacher retired after 28 years of teaching there, and (without her knowing) every single child at school, hundreds of them, had been taught a song just for her, and on her final day of school last year they sang to her, and a lot of people cried. (Our music teacher has not been replaced. What kind of school has music teachers anymore?)

I think sometimes people underestimate how good teachers are at doing their jobs, what experts they are in their professions. I absolutely know that the role of teachers in our society is shockingly undervalued, the incredible role these people play in our families’ day-to-day lives. A good teacher can change a life, and imagine what happens to a life when a kid has one good teacher after another. I sat in the office this morning, and said hello to a number of these teachers, and thought about what we’re trusting them with, up there with heart surgeons and bridge builders. Is there anyone more important?

Sit in a school office for a morning, and you get a glimpse into your community. Harried parents straggling in late, kids with disruptive behaviour, students living with their mothers in shelters because they’re fleeing family violence and the special needs that come with that. Our school specifies 10% of all money raised throughout the year go into a fund for students who are most in need, and this money has paid for eye glasses, winter clothing, gift cards at the holidays for families who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford things. If a child shows up at school without a lunch for reasons other than a forgetful dad or mom, they will be quietly accommodated. Parents turn up with hugely pressing concerns which they seem blasé about, and others hysterical about incidental problems, and all of them are treated with care and consideration, and some other kid will arrive because he has a stomach ache and somebody will call his mom, and the day will continue, even after all my papers are filed. There is no such thing as extraordinary there, because everything is extraordinary all the time, and it works, because the people do, in spite of everything. I can’t imagine who’d we be without them.

September 25, 2018

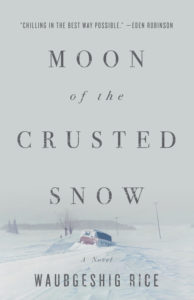

Moon of the Crusted Snow, by Waubgeshig Rice

“‘Yes, apocalypse! What a silly word. I can tell you there’s no word like that in Ojibwe. Well, I never heard a word like that from my elders anyway.”

“‘Yes, apocalypse! What a silly word. I can tell you there’s no word like that in Ojibwe. Well, I never heard a word like that from my elders anyway.”

The first sign that something is wrong is the home satellites stop working, TV screens gone dead. “We might actually have to have a conversation,” Nicole tells her partner Evan when he comes from hunting a moose, and they will pass the evening without their usual entertainment. And by the morning, they’ve lost cell phone service, cell towers a pretty recent arrival in their remote northern community anyway—only built because contractors for the south wanted a signal while they built the hydro dam, and the tower stayed even after they were gone. But there’s no signal now, and soon the landlines will stop working, and the power grid will cease to function. Which raises two big questions: What has happened to the rest of the world? And the more immediately pressing one: how will their community get through the winter?

On the latter point, Evan has some advantages—he can hunt and has been storing food; he’s been reconnecting with the traditions of his Ancestors and this wisdom will guide him; and he and Nicole have built a stable life for their family, which will provide the emotional sustenance necessary to survive a dark and barren winter. But they are challenged when Southerners begin to arrive in the community, fleeing the devastation of towns and cities in the south—one of these men in particular is dangerous. And other members of the community prove to be susceptible to this man’s influence, which begins to divide them at a time when cooperation is essential.

Moon of the Crusted Snow is Waubgeshig Rice’s third book, and it’s gorgeously designed, the story itself quiet and subtle, but fast-paced with heavy overtones. Evan’s reconnection with Anishinaabe traditions as his community is becoming disconnected from the world around them sets up an interesting disjunction, and Rice shows the ways that he has consciously woven these traditions into the life of the family he’s created with Nicole, and how these connections serve them when the situation becomes particularly dire. Evan is also learning the Ojibwe language of his people, and this language is included seamlessly in the text without the use of italics or translation, which offers the text an additional layer of meaning to those who can read Ojibwe—does “zhaagnaash” really mean “helpful friend” I wonder, when used toward Scott, the man who has arrived in their community with big guns and survivalist tendencies?

And yes, there is no Ojibwe word for “apocalypse,” which Evan learns through a conversation with Aileen, an Elder whose teachings he carries with him. Aileen explains to Evan that their world isn’t ending—it already ended long ago when settlers arrived. “When the Zhaagnaash cut down all the trees and fished all the fish and forced us out of there, that’s when our world ended.” But they survived—this is her point. They learned to adapt, and to survive, even as their children were taken and abused in residential schools for generations. “But we always survived,” she tells Evan. “We’re still here. And we’ll still be here, even if the power and the radios don’t come back on, and we never see any white people ever again.”

The ending of this novel is powerful, unexpected, and while deeply satisfying, it’s also ambiguous in a really fascinating way. Moon of the Crusted Snow is a terrific, gripping novel, and one of the highlights of my literary autumn.

September 21, 2018

Hansel & Gretel, by Bethan Woollen

Things get a bit weird in Bethan Woollen’s Hansel & Gretel, which is a book you’ve probably got to get if you’ve read her Little Red and Repunzel and you have completist tendencies. See photo below for what I’m talking about:

Once again, Woollvin is revising a fairy tale we think we know, but this time she’s telling it from a different point of view. Yes, a house made out of gingerbread might turn out to be all too tempting for a brother and sister who are lost in the woods, but luring children wasn’t what the good witch Willow had in mind when she conjured the spell to build her house. A miscalculation, maybe, but when Hansel and Gretel come tramping through the woods scattering breadcrumbs, which are sure to lure mice and other pests and therefore put Willows gingerbread house at risk, she politely asks them to clean up the crumbs, which they refuse. And when she has her back turned cleaning up the crumbs herself, the recalcitrant pair begin snacking on the house, which might be the final straw for some witches, but not this witch, who determines Hansel and Gretel must be hungry and invites them to come in for dinner.

It turns out that Hanesel and Gretel have no manners at all, however, and they gobble up all of Willow’s food, then start messing with her spells and wands, turn the black cat gigantic, and then Gretel stuffs Willow into the oven so she and her brother can continue to make trouble—but then the house is so full over magic, it explodes: “It was only made out of gingerbread after all.”

And so it is here that Willow finally decides to get her comeuppance, concocting a nasty bit of revenge that Hansel and Gretel completely had coming, and which hearkens back to a bit of fairy tale darkness worthy of Grimm’s.

September 19, 2018

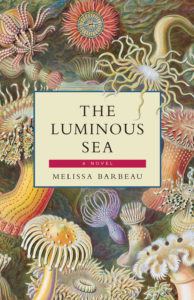

The Luminous Sea, by Melissa Barbeau

If, like me, you are drawn to Melissa Barbeau’s debut, The Luminous Sea, because of its cover (Ernst Haeckel!) then keep on going because the novel itself is just as gorgeous and rich with wonder. Beginning with Vivienne, a university researcher charged with collecting data on the phosphorescent waters off the coast of Newfoundland, not anticipating her next catch—a sea creature unlike anything anyone’s ever seen before. A little Shape of Water, but there’s no sex in the bathtub, and Vivienne and her supervisor, Colleen, create a tank out of a chest freezer instead. And the creature is a female, or at least Vivienne keeps calling it “she,” even as she’s admonished for the anthropomorphizing. Dynamics in the lab are getting complicated—Colleen’s superior arrives and attempts to take control of the discovery, and in a shocking act of violence (exquisitely rendered in prose like you’ve never seen before) he tries to subdue Vivienne as well. Meanwhile, Colleen is carrying on an affair with a local cafe owner whose wife is wise to it all and spends her time making preserves out of such unlikely things as jellyfish, and Vivienne is only there at all because she’s run away from a broken relationship with her girlfriend in the city. And in the meantime, the creature is not doing well in the tank (“Three days in and scales were coming off in her hand when she touched her, like flakes of opalescent pearls…”), and it might be up to Vivienne to save it. So that this extraordinary novel whose sentences and imagery shimmers and shines is also taut with tension, fast-paced, impossible to put down. But oh, the writing! It’s the writing I keep going on about. The following is my favourite part:

If, like me, you are drawn to Melissa Barbeau’s debut, The Luminous Sea, because of its cover (Ernst Haeckel!) then keep on going because the novel itself is just as gorgeous and rich with wonder. Beginning with Vivienne, a university researcher charged with collecting data on the phosphorescent waters off the coast of Newfoundland, not anticipating her next catch—a sea creature unlike anything anyone’s ever seen before. A little Shape of Water, but there’s no sex in the bathtub, and Vivienne and her supervisor, Colleen, create a tank out of a chest freezer instead. And the creature is a female, or at least Vivienne keeps calling it “she,” even as she’s admonished for the anthropomorphizing. Dynamics in the lab are getting complicated—Colleen’s superior arrives and attempts to take control of the discovery, and in a shocking act of violence (exquisitely rendered in prose like you’ve never seen before) he tries to subdue Vivienne as well. Meanwhile, Colleen is carrying on an affair with a local cafe owner whose wife is wise to it all and spends her time making preserves out of such unlikely things as jellyfish, and Vivienne is only there at all because she’s run away from a broken relationship with her girlfriend in the city. And in the meantime, the creature is not doing well in the tank (“Three days in and scales were coming off in her hand when she touched her, like flakes of opalescent pearls…”), and it might be up to Vivienne to save it. So that this extraordinary novel whose sentences and imagery shimmers and shines is also taut with tension, fast-paced, impossible to put down. But oh, the writing! It’s the writing I keep going on about. The following is my favourite part:

“A long stainless steel table is in the middle of the room. Next to it a second table made from a wooden door laid across two wooden sawhorses and covered with sheets of plastic. Instruments and vials, pincers and thermometers and gloves, measuring tapes and suction-cupped monitors are arranged in near rows on top of it. The doorknob is still attached to the door and makes a small mound underneath the plastic. Vivienne wonders if they have not made some kind of underestimation when considering door security. It seems as if at any minute someone might turn the handle on the supine door, throwing scientific instruments across the room; that someone will will up through the horizontal doorway, like that party trick where someone climbs an imaginary set of steps in the carpet behind the couch.”

Do Not Underestimate Door Security turns out indeed to be one of the novel’s many morals, and maybe (definitely) I’ve got a thing for door imagery anyway, but that paragraph for me is emblematic at how beautifully imagined this novel is, its realities and its many possibilities. There is a generous expansiveness at the heart of the book, doorways onto doorways, but it never grows too strange and mystical and stays controlled, anchored in the physical world, with such attention to accuracy and detail, scientific, like the image on the cover. Melissa Barbeau is an extraordinary writer, and I can’t stop talking about this book.

September 18, 2018

Transcription, by Kate Atkinson

This post is less a book review than “How I Spent My Weekend.” I don’t really know that I’m capable of reading a Kate Atkinson novel critically, or if I’d even want to be. I read them for pure enjoyment, delight, for her narrative tricks, and the way she plays with history, and story. For the little twists that make her books so unforgettable, and how they get lodged in the mind, like how I’m still even thinking of Behind the Scenes at the Museum, even though I read it thirteen years ago.

Since then, Atkinson has waded into detective fiction (igniting my own love affair with the genre) with her Jackson Brodie novels, and then in her two most recent books exploring historical fiction, as ever probing at the limits of what a novel can hold, just how far it can stretch. And that her latest is a spy novel set during during WW2 and also in 1950 is not at all incongruous. Questions of duplicity, reliability, truth and lies, and how History agrees with the factual record are what has fascinated Atkinson from the start of her writing career. I’ve always said that all her books have been mysteries (and maybe all books are in general) and maybe they’ve always been spy novels too.

Transcription is about Juliet Armstrong, something of a cypher, who gets a job with MI5 in 1940 transcribing meetings between a government agent and people who believe they’re reporting state secrets to the Gestapo. As with any book about English fascism during the 1930s/40s (including Jo Walton’s Small Change series) there is a contemporary resonance, although it’s subtle here. In addition to her transcribing, Juliet is enlisted to infiltrate The Right Club, a group of German-sympathizers, taking on an additional identity. And all of these war-time activities come back to haunt her a decade later as she’s working at the BBC (Atkinson has said this part of the story was inspired by Penelope Fitzgerald’s Human Voices) and finds old associates in close proximity again. What do they want from her? What does she have to offer them? Is this just paranoia on her part—there are references to the movie “Gaslight.” How much can the reader trust Juliet at all?

I loved this book—but of course I did. I read it in two days and delighted in that very rare and always exquisite, “I’m reading a Kate Atkinson novel for the first time” feeling. And like all her books, it will bear rereading, even once the twist is known. Because Kate Atkinson is always about more than just tricks, but instead about textual richness, and all the clues you missed that were glaring all along.

September 17, 2018

Motherhood and the Map

In July, Lauren Elkin wrote an essay about a new and sudden influx on books about motherhood, and I rolled my eyes at the idea. Because of course Lauren Elkin is pregnant with her first child, which is around the time that most literary people discover the existence of a motherhood canon. “Motherhood is the new friendship, you might say. These are books that are putting motherhood on the map, literarily speaking, arguing forcefully, through their very existence, that it is a state worth reading about for anyone, parent or not.” Which annoyed me not just because after nearly a decade of motherhood, because of course it’s been on the map all along—and I even did my part to expand its boundaries by editing The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014. But also because Elkin’s discovery of motherhood reminds me of my own earnest revelations of a decade ago, that parenting indeed is not “a niche concern,” and it’s a little embarrassing to see one’s naivety reflected in such stark terms.

In July, Lauren Elkin wrote an essay about a new and sudden influx on books about motherhood, and I rolled my eyes at the idea. Because of course Lauren Elkin is pregnant with her first child, which is around the time that most literary people discover the existence of a motherhood canon. “Motherhood is the new friendship, you might say. These are books that are putting motherhood on the map, literarily speaking, arguing forcefully, through their very existence, that it is a state worth reading about for anyone, parent or not.” Which annoyed me not just because after nearly a decade of motherhood, because of course it’s been on the map all along—and I even did my part to expand its boundaries by editing The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014. But also because Elkin’s discovery of motherhood reminds me of my own earnest revelations of a decade ago, that parenting indeed is not “a niche concern,” and it’s a little embarrassing to see one’s naivety reflected in such stark terms.

The other week, two of my library holds came in at once: Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, by Kate Manne, and And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I was Ready, by Meaghan O’Connell. I read Down Girl at once, and found it illuminating and really profound. I’ve since had to return the book—there are many holds on it after mine—but if I still had a copy here I’d been sharing the lines where she writes the misogyny inherent in our understanding that the history of feminism occurs in waves, each one sweeping away whatever came before. Instead of us there being a more constructive model of this history, something indeed that is cumulative. I was struck by this idea, by the way that waves must undermine us. As Michele Landsberg explains in Writing the Revolution: “Because our history is constantly overwritten and blanked out…., we are always reinventing the wheel when we fight for equality.”

I didn’t pick up Meaghan O’Connell’s memoir at all, however, until I received a note from the library that it was two days due. I’d been resisting the book for ages, since seeing it in the bookstore and deciding I didn’t want to pay the price of a hardcover for a book that was slight, so I was content to be the hundredth-something library hold, and even once I brought the book home, as I’ve said, I still didn’t read it. Partly for the same reason I found Lauren Elkin’s essay annoying. “We have lacked a canon of motherhood, and now, it seems, one is beginning to take shape.” OH GOD, NO. (Note: Please read my review of Val Teal’s amazing and irreverent 1948 mothering memoir, It Was Not What I Expected: “It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens.”) I’d read enough motherhood memoirs for one lifetime, I decided. There was indeed nothing new under the sun, even if you happen to be raising your baby in Brooklyn.

But then it wasn’t a very long book—the very reason I hadn’t bought it. Perhaps I could even get it read in two days (because such expansiveness is possible in the life of a mother whose children are nine and five). There were many holds on this book as well and it could not be renewed, so I picked it up and started reading, and what happened next, like motherhood, was not at all what I’d expected.

Reader: I really, really liked it, this story of a woman who got pregnant when she was 29 and decided to have a baby before she even owned a home or a car. Unlike O’Connell, my baby was planned when I got pregnant when I was 29, but we were similarly missing the house and car and career stability (actually we’d just decided to skip those) and there were people who, when they heard I was pregnant, had asked me, “Oh, Was it planned?” I identified so much with O’Connell’s story of motherhood before she was ready, and it brought back so many memories I’d forgotten about altogether—like when she jumps up from the table at last once a week to run to the bathroom because she’s convinced she’s started to miscarry and then comes back sheepishly, “False alarm.” How the pregnancy never feels real, except for about forty minutes after she’s had a sonogram. About reading Ina May Gaskin and deciding that you too can be a hero. And once her baby is born—that failure of imagination. The double standard of a society that demands you breastfeed but doesn’t know where to look when you do it. O’Connell writes that she’d known it would be hell, but had imagined the hell would be logistical instead of emotional. And that was the part where I put my finger on the line of text and shouted, “Yes, this exactly.”

I’d forgotten so much of it—and I have probably read and written about motherhood more than the average person. But so much of the story had disappeared from my consciousness, swept away—like as a wave, as it will. And I’d even decided that stories of new motherhood were no longer relevant to me, that I was done with al that. The same problem as Lauren Elkin but in reverse. Scoffing, of course, there’s always been a motherhood canon, but now it’s dusty on the shelf and I don’t even need to read it.

There might be something to the waves, something more than misogyny. I wonder if men’s lives are more linear than women’s, whereas I know that in my own experience, with motherhood in particular, my self has been continually overwritten. As it has been again now that my children are more independent, and as it will be when they get even older, and then with menopause—all these changes. I don’t remember who I was before. I don’t remember when I ever needed those books. Sometimes I pick them up and read my notes in the margins though, and it’s like they were written by a stranger.

September 14, 2018

In the woods, on the radio, and online!

We had an amazing time at the Dunedin Literary Festival “Words in the Woods!” last weekend, where I had the privilege of moderating a panel with Karma Brown, Tish Cohen, and Uzma Jalalludin. It was a very good day and left me excited for my next event, which takes place on September 23 in Huntsville as part of Huntsville Public Library’s Books and Brunch series. I’ll be there with Hannah Mary McKinnon and K.A. Tucker, and all of us appeared on the most recent episode of the library’s very own radio show (how cool!) Keeping Up the Librarians—you can listen to it here. And I was also happy to take part in the “Behind the Scenes With Book Reviewers” series at the Hamilton Review of Books, which was published this week—go here to learn all my book reviewing secrets.

September 14, 2018

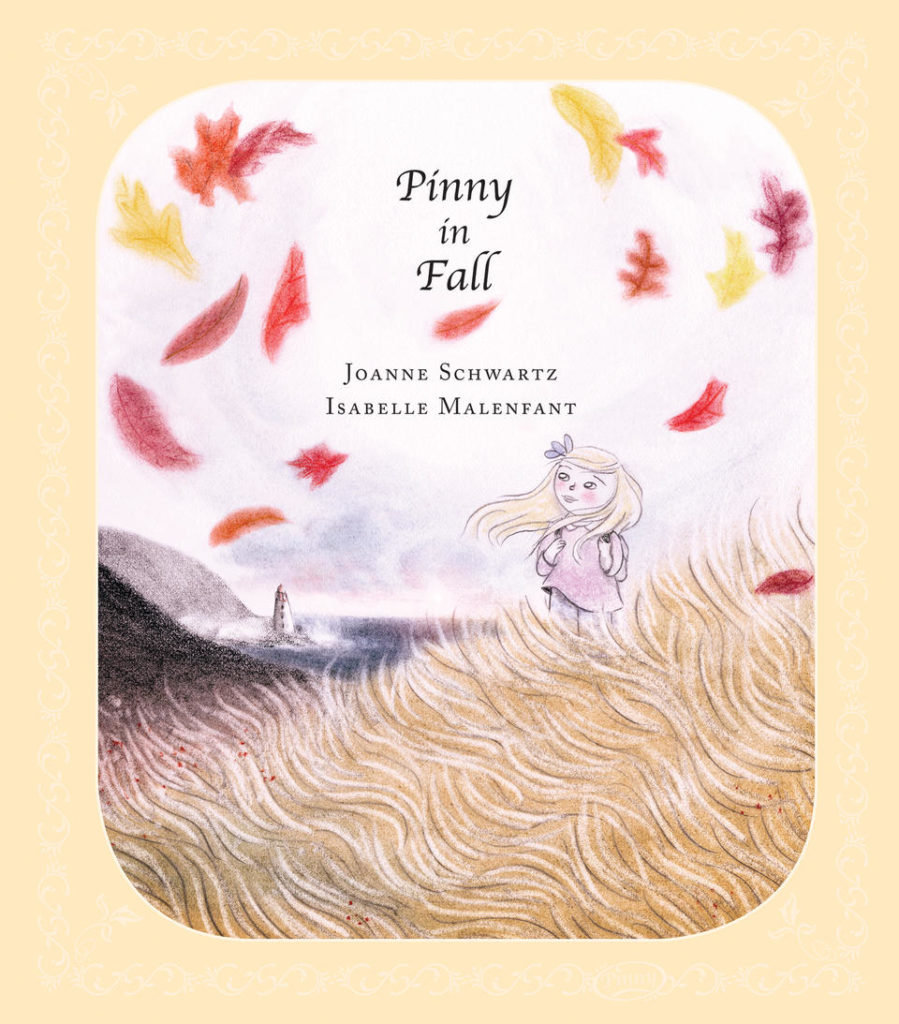

Pinny in Fall, by Joanne Schwartz and Isabelle Malenfant

Before Joanne Schwartz was taking over the literary world with her beautiful picture book, illustrated by Sydney Smith, Town Is By The Sea, she was author of a whole bunch of other lovely picture books, among them the perfectly delightful Pinny in Summer, which we fell in love with two years ago and inspired us to bake a cake. And so we’ve been looking forward to Pinny’s return with Pinny in Fall, a collection of four miniature adventures that demonstrate the amazing possibilities of a single day, smallness (and slowness) writ large in an approach that reminds me of the Frog and Toad books.

“Does Pinny have parents?” my children wonder when we read this book, and I tell them that her parents are probably curled up in comfortable chairs somewhere reading. Which means that Pinny can do whatever she wants to—in the first story she wakes up and does her stretches, and then packs a small bag for her morning walk, with a sweater, a rain hat, a snack, and her book. Plus her treasure pouch, which was hanging on a hook by the door.

On her walk to the lighthouse, she encounters her pals, Annie and Lou, and they play tag in the wind and the fog, and then Pinny shares her snack and they read poetry. “The sun slipped behind the clouds, once, and then it was completely gone.” The fog is getting thicker in the third story (which Malenfant renders beautifully in her art) and Pinny and her friends have to rush to help the lighthouse keeper sound the foghorn and light the light. With their help, a ship safely navigates its way along the rocky shore, and the lighthouse keeper rewards the children: a piece of beach glass for each of them. Pinny slips hers into her treasure pouch.

And in the final story, Pinny is sipping hot chocolate by her window. As with Pinny in Summer, the colours in this book are particularly and beautifully hued, and the light that shines into Pinny’s room at the end of the day continues to be the most wonderful thing. This time coloured by the leaves falling outside her window: “A Special Kind of Rain.” After going outside to soak in it, she comes back in and the day is nearly done—her takes the beach glass from her treasure pouch and sets it on the window. “The glass had been washed so smooth by the ocean, it glowed in the twilight like a tiny bacon of light.”

Pinny in Fall is a gorgeous, old-fashioned story with such reverence for language, and wholly infused with a sense of wonder that will inspire readers to look at the world differently and seek out adventures of their own.