October 17, 2017

A far cry from Mr. Stillingfleet’s stuff

I’ve never been to the Victoria College Book Sale on opening day before, because it’s always on a Thursday and you have to pay $5 to get in, but I hadn’t planned my life well during the weekend the sale was happening last month, and my only chance to go at all would be during the ninety minutes between when the sale kicked off at 2pm and when I had to pick my children up from school at 3:30. So I cobbled together the admission fee, literally out of dimes and nickels from a jar in my kitchen, which made for very heavy pockets, but I got there, and learned of just one distinction between the Victoria College Book Sale on its first day and all the days thereafter: there are Barbara Pym books for sale.

It’s difficult to find used copies of Barbara Pym novels. Her readership was never huge enough, at least not in Canada, as compared to writers like Margaret Drabble, Hilary Mantel and Penelope Lively, whose novels are mainstays at secondhand bookstores (which is the way that I fell in love with all of these writers, and others). I like to think, however, that it’s not just that Pym’s readers are few and far between, but that they’re also quite devoted. The secondhand copies of Barbara Pym novels that I do have came from a house contents sale in my neighbourhood after the death of its elderly owner (which in itself is kind of Pymmish), and that’s the only way I’ll ever be getting rid of Barbara Pym books, by which I mean: over my head body. (I imagine they’re easier to find in secondhand bookshops in England; also, many of her works have brought back into print by Virago Modern Classics with fun cartoonish covers in the last ten years and I’m sure those copies are turning up in charity shops).

Anyway, finding Barbara Pym novels at the Vic Book Sale was exciting enough, but even more remarkable was finding one I hadn’t read yet. I thought I’d read them all, including a collection of her letters and another of unpublished short fiction, and the first book she ever wrote, Crampton Hodnet, which wasn’t published until after her death. I thought I’d spanned the entirety of the Pymosphere, and was content to spend the rest of my life then just rereading her, at least once a summer and maybe even more so, but then there was An Academic Question. I’d missed it altogether. Also published after her death, written during her wilderness years in the early 1970s (before she was “rediscovered” and brought back into print, winning the Booker Prize in 1977 and publishing two more books before her death in 1980).

I started reading An Academic Question on Friday night because I’d been reading A Few Green Leaves (the official newsletter of the Barbara Pym Society) in the bathroom (as you do) and then checked my email to find a reminder that I hadn’t yet renewed my Pym Society membership for 2017. I did so, and took note of the universe conspiring to send me in a Barbara Pym direction, and I’ve already got a backlog of books I have to write about anyway so this would be an excellent opportunity to read for fun and not have to write about it at all.

Take note: I am writing about it. Barbara Pym never fails to incite…

The novel starts off a little roughly. In her note on the text, Hazel Holt writes that it’s cobbled together from two drafts, one in first person and the other in third. Before the book’s spell had taken hold, I kept getting caught on clunky prose and repeated words..but then at some point these problems ceased or else I stopped noticing them. As per Holt’s note, Pym wrote to Philip Larkin of the novel in June 1971: “It was supposed to be a sort of Margaret Drabble effort but of course it hasn’t turned out like that at all.” Which interested me—I remember reading about Pym’s relationship to Drabble’s work in the years when Pym herself wasn’t being published, deemed irrelevant while Drabble herself was very fashionable, her antithesis.

You can see what Pym was up to here—this is a story of a young faculty wife whose sister has had an abortion and lives in London with a man who designs the sets for the news program her husband’s colleagues appear on, all the while the students at the university are going through a period of unrest. In a superficial way, this is Drabble’s milieu—but Pym can’t help but spin it in her own way. It’s the interiority of her protagonist, her doubts and questions, her sense of humour. Caroline is undeniably Pymmish in her preoccupations, spending most of her time with her gay best friend Coco who dotes on his high maintenance mother. While Drabble’s characters are all on the verge of slitting their wrists in a bathtub, Caroline is unfailingly stoic, even at a remove:

‘What was the point of it all?’ Kitty had asked me plaintively, and I felt that for her the evening had been a disappointment, as indeed so many evenings must be now. And what had been the point, really? A few gentle cultured people trying to stand up against the tide of mediocrity that was threatening to swamp them? I who had hardly known anything different could sympathize with their views but for myself I didn’t really listen to the radio; I went about my household tasks, such as they were, absorbed by my own broody thoughts.

And while this is one of Pym’s rare novels that doesn’t contain a single curate, let alone a mention of The Church Times, has only handful of references to jumble sales and the characters drink coffee instead of tea (I KNOW!), the humour is still wryly, undeniably Pymmish. The following passage would never be found in a Margaret Drabble novel:

We sat drinking cups of instant coffee and smoking, commiserating with each other. An unfaithful husband and a dead hedgehog—sorrows not to be compared, you might say, on a different plane altogether. Yet there was hope that Alan would turn to me again while the hedgehog could never come back.

The book wouldn’t work, Pym felt, according to Holt, for its cosiness, and it was remarkable how often the word “cosy” appears in the text (alone with the word “detached”). Which got me thinking about the literary implications of cosiness, as opposed to grittiness, I suppose. Thinking of cosy made me think of rooms, of comfortable sofas, piles of books on the table, interesting items on the mantel—all of which are things that furnish Pym’s books, including this one. Cosy isn’t fashionable, it’s true, what what it is instead is timeless, which might be why we’re reading Pym today while Margaret Drabble’s early novels seem so dated and are out print.

Pym’s Caroline is detached from her life as faculty wife—her husband has proved to be less interesting that she thought he might be, he’s been unfaithful, and she finds herself at a loss as to how support him in his work as one expects she should. She finds motherhood a bit boring and her daughter is cared for by the Swedish au pair anyway. Apart from her friendship with Coco, Caroline doesn’t have anyone to have real conversations with, and when she does talk to Coco, he has no qualms about finding her provincial life kind of tiresome. She spends some time reading to Mr. Stillingfleet, a retired professor at an old people’s home, revealing to her husband that the professor keeps a box of academic papers by his bedside…which ignites her husband’s interest in visiting the frail old man, so he can scoop material from the box and pull an academic coup over his superior. And then Caroline is left with the ethical question of what to do with the stolen paper afterwards, and just where her loyalties lie, and what compromises indeed she is willing to make in the name of her husband’s success…

“‘Hospital romances,’ I said to Dolly that evening when she called around to see us. ‘That’s what I’m reading now. It’s a far cry from Mr. Stillingfleet’s stuff.”

‘Maybe, but it is all life,’ said Dolly in her firmest tone, ‘and no aspect of life is to be despised.”

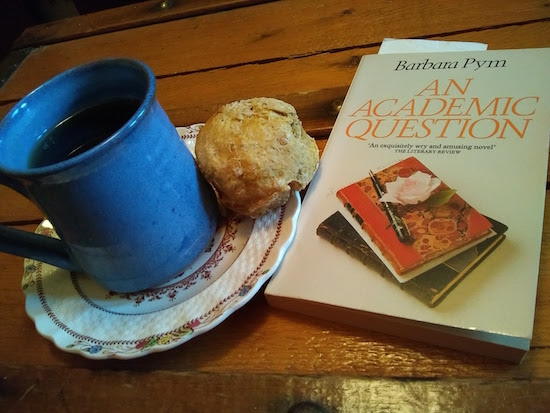

What is that bun thing sitting on Grandma’s plate — a “cozy” illustration of your piece, I must say. But really — have you now mastered the art of biscuit/scone making, or did you buy said piece? If you did make it I’m jealous. Not only do you write blogs and BOOKS, you bake yummy things.

PS. MY apologies for lowering the literary tone of your piece. It was first-rate!

Because of your mention of Pym the other day on Instagram I picked up one of my many copies I haven’t read yet – purchased from my treasured used books store in Tamworth Ontario which has not only a large selection of Pym novels but also Jennifer Johnston who I can’t find anywhere else! Anyway, I’m currently reading A Glass of Blessings and dying over Wilmet Forsyth. This book is making me all kinds of anxious but I can’t stop reading. I guess I too should join the Barbara Pym society.