February 5, 2017

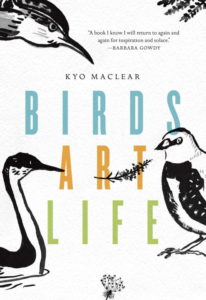

Birds Art Life, by Kyo Maclear

“…what he really taught me was that the best teachers are not up on a guru throne, doling out shiny answers. They are there in the much beside you: stepping forward, falling down, muddling through, deepening and enlivening the questions.” —Kyo Maclear

“…what he really taught me was that the best teachers are not up on a guru throne, doling out shiny answers. They are there in the much beside you: stepping forward, falling down, muddling through, deepening and enlivening the questions.” —Kyo Maclear

In her book, Mommyblogs and the Changing Face of Motherhood, my friend May Friedman refers to the value of “critical uncertainty in practice,” as opposed to “the generalizing trap of expert discourse.” Indeed the best blogs, and life itself, are all about “stepping forward, falling down, muddling through, deepening and enlivening the questions.” And while Kyo Maclear’s new memoir, Birds Art Life, is no blog—its prose is polished perfect; by design, the book is an object most exquisite—it has a bloggish spirit, with its wide vistas, room to wander, and the miraculous and serendipitous way that one thing seems to lead to another.

It’s not a book about birding, or even discovering birding—it’s a book that’s far more vicarious, and stranger than that. Here is a book about a year Maclear spent hanging out with a birder, figuring out what makes him tick. Developing a passion for birds in the process, but that’s not the point of this memoir. Yes, there are birds, but it’s also about family, and history, about caregiving, marriage, waiting, reading. About darkness, and prisons, and action in dangerous times. It’s about cities and nature, about the hearts of things and also their edges.

“Life and death. Survival and extinction. The common and the rare. The robust and the disappearing. I had come to see that birding was about holding opposites in tension. It elicited a twoness of feeling—both reassuring and dispiriting—especially in a city where so little landscape had survived modernity’s onslaught. In that twoness was a mongrel space between hope and despair.” —Kyo Maclear

I’ve loved Kyo Maclean’s work since reading her first novel, The Letter Opener, in 2008. In 2012, she released her second novel Stray Love along with the picture book, Virginia Wolf, and created a list at 49thShelf of Picture Books for Grown-Ups, and what I love about Birds Art Life is that she’s now herself created such a thing. First, because the book is illustrated with photographs of birds by her birding friend, Jack Breakfast, and also with Maclear’s own line-drawings, which add whimsical charm to the pages in a the fashion of Maira Kalman. And second, because of how the stories in this memoir contain echoes of her picture books, works that are so rich in thoughtfulness and wisdom—and now grown-up readers get to read it all too.

But it’s a particular kind of wisdom. I feel as thought Maclear herself would feel uneasy with being declared as wise, but it’s the kind of wisdom she’s talking about in the excerpt I quoted at the beginning of this post. The kind of wisdom that comes from falling down, from enlivening questions, rather than supposing there are even answers.

The year Maclear captures in her memoir is a dark one, although it comes with requisite moments of light. But she’s been caring for her father during a period of illness; she’s still negotiating her relationship with her mother; she worries about her younger son and identifies with his anxiety; close to the end of the year, two close friends of their family are imprisoned in Egypt and news of their fate is held in fear and uncertainty. And as I read this book yesterday, I was thinking that this is precisely the very book I need to be reading right now, not to escape from the things outside my door that make me afraid these but instead to “enliven the questions.” A book that—like so much that I’m reading these days, like so many books that are saving my life—helps me negotiate that space between hope and despair.

Leaning towards the hope, even.

February 3, 2017

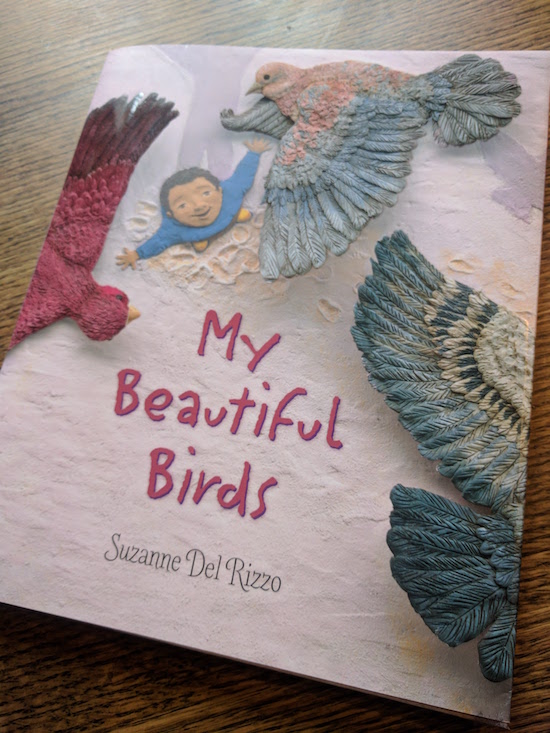

My Beautiful Birds, by Suzanne Del Rizzo

As weird and terrible as the world can be, I don’t spend a lot of time, as the modern problem goes, worrying about “how I’m going to explain it to my children.” As I’ve written before, I relish awkward conversations. But I was thinking about this idea yesterday, about how incongruous it must be to be both a parent and somebody who wants to see refugees restricted from finding sanctuary in their country and community. What do these people teach their children about helping others, I wonder. Do they ever worry about the gap between their messages?

“As a parent,” somebody told me on Twitter this week, “my job is to protect my children from danger.” Hence their support of UnpopularDonald’s Muslim Ban. And the logical next question, although I didn’t ask it because this was Twitter and there was really no point, is “Isn’t that precisely what so many refugee families are doing though? And so surely as a parent then, you can recognize the humanity in these people, that they are guided by the same impulses that direct you, except that their homes have been destroyed by years and years of war and your fear is based on a sense of otherness and is also statistically irrational?”

The first time I was happy after November 9 2016 was a few weeks later at the Canadian Children’s Book Awards, and not just because I’d had more than a few glasses of wine. But it was because of the spirit that night, the speeches of the presenters and winners that acknowledged the darkness of the moment we’re currently embroiled in and that books really were one sure way to kick at the darkness, children’s books in particular. Books that bridge the distance between here and there, between us and them, and recognize the humanity common to all of us.

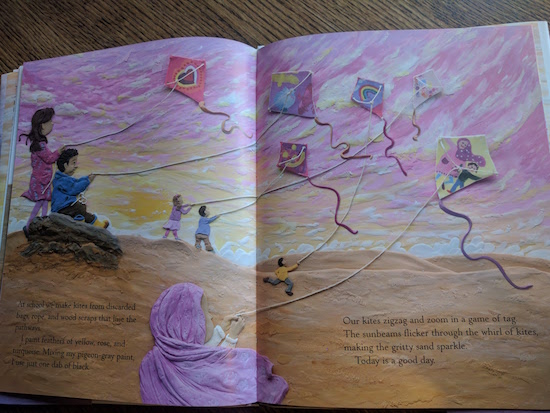

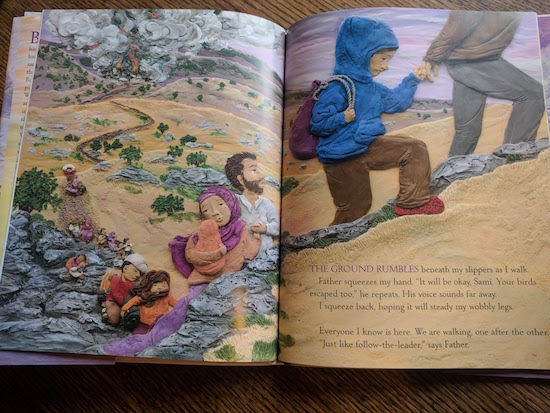

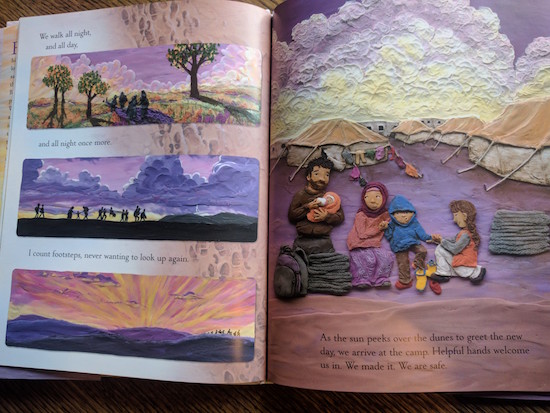

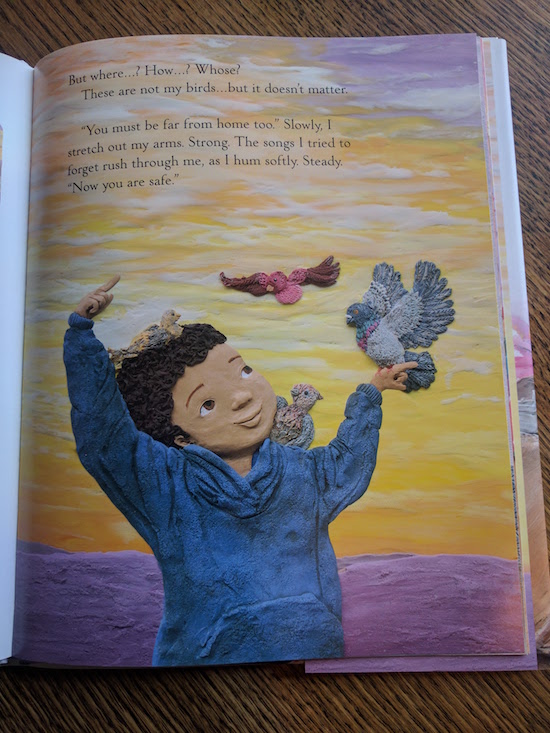

In Suzanne Del Rizzo’s picture book, My Beautiful Birds, a young Syrian boy is forced to leave his wartorn home and make the long journey to the relative safety of a refugee camp. The story is enlivened by Del Rizzo’s plasticine illustrations with their rich purple and golden hues. Of all the things that Sami has left behind. it’s his pigeons he misses the most, the birds he fed and kept and as pets. Although his family does their best to create a home in the camp—planting a garden, buying things in the small shops started by their neighbours—this new life is anything but sure: “Days blur together in a gritty haze. All I have left are questions. What will we do? How long will we be here?” The idea of the birds and their freedom symbolizing everything that’s been lost to Sami.

Del Rizzo shows Sami’s grief and sadness with thick black lines that overwhelm the pictures he tries to paint of his beloved birds, the black paint taking over his art like a storm. Where he finds solace, though, is in the sky, one thing that is familiar to him, “wait[ing] like a loyal friend for me to remember.” In the clouds, he sees the shapes of his birds: “Spiralling. Soaring. Sharing the sky.”