May 13, 2016

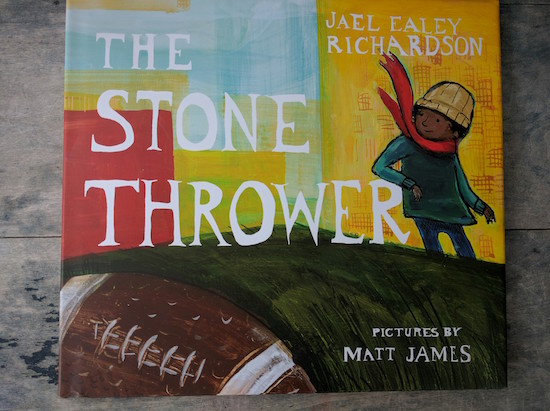

The Stone Thrower, by Jael Ealey Richardson and Matt James

Because this is the week that began with The Festival of Literary Diversity, it only seems fitting to end it with The Stone Thrower, a brand new picture book written by The FOLD’s executive director, Jael Ealey Richardson and illustrated by Matt James (of the award-winning I Know Here). Richardson has told the story before of how an impetus for the festival was her experience promoting her first book, a non-fiction biography of her father, CFL Quarterback Chuck Ealey, and having an indie bookstore owner decline her invitation to visit with the explanation, “This town is very white.”

“There are so many gatekeepers – publicists and sales reps, and bookstore owners, and all these people have to buy into the story in order for you to have any chance,” Richardson explained in her interview with Quill & Quire, and The FOLD emerged as part of an effort to find a way to change that. And now The Stone Thrower is the other creation that Richardson has brought into the world this spring, her father’s story told in picture book form, and it’s every bit as extraordinarily good.

The first time I finished reading this book to my children, we closed the cover a little bit breathless.

“That was really good,” said my oldest daughter, and we made sure to read the book again at night before bedtime so that her dad could know just what we were talking about.

He was also very impressed.

And what do I mean by the fact that this is a book that took our breath away? Because we read a lot of books. We know from good. But rare is the book like this one, with a moral tone as gripping as its story, full of suspense and ultimate triumph, spots of humour, rich and warm illustrations, and prose that feels wonderful in your mouth when you say it.

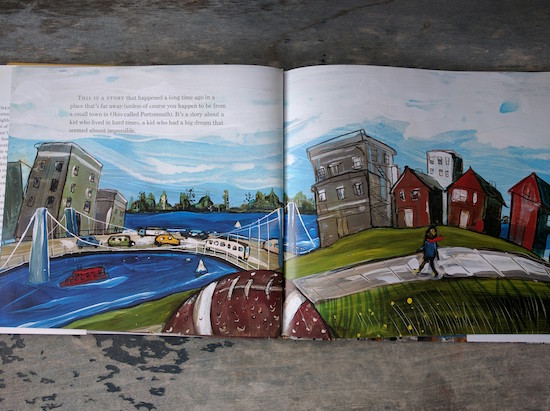

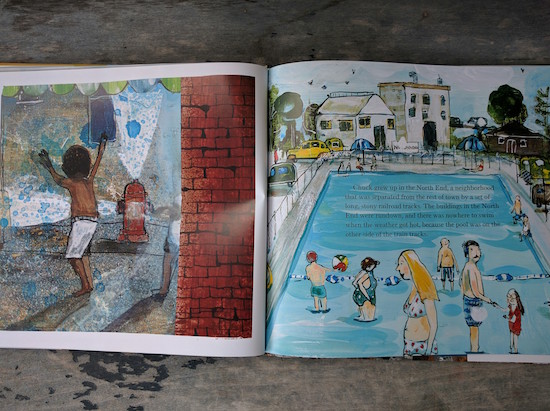

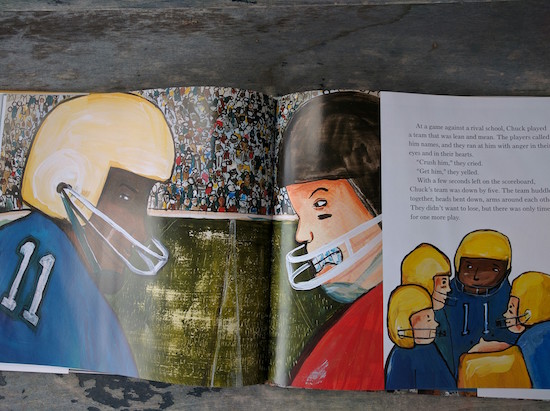

It is the story of a boy called Chuck who grew up in Portsmouth, Ohio, during the 1950s. “It’s a story about a kid who lived in hard times, a kind who had a big dream that seemed almost impossible.” And the odds are against Chuck, a Black kid growing up on what was literally the wrong side of tracks. James’ illustration shows Portsmouth’s white residents cooling off on summer days in a swimming pool, while the kids on the North End, like Chuck, played in the spray from opened-up fire hydrants. Chuck’s mom works hard, but she dropped out of school when she was young and makes very little money. She wants a different kind of life for her son.

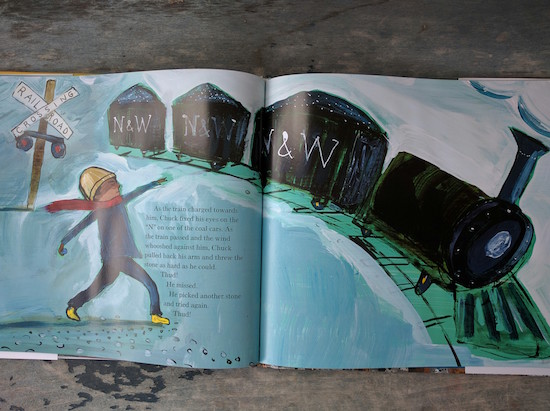

“Those coal trains that come through, they don’t stop here,” she said. “I want you to be just like that. Do you remember where you’re going, son?”

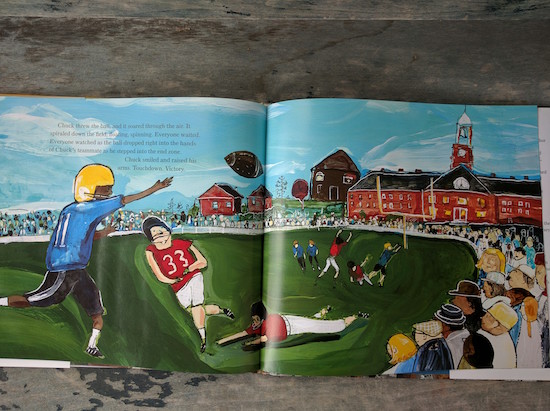

While walking down by the tracks, Chuck picks up a stone as the train comes by. Richardson makes her story rich with atmosphere: “The ground began to rumble, and the train tracks shook. The stones along the tracks jumped and bounced like hot kernels of popcorn.” Chuck aims for the N on the N&W on the boxcars (for Norfolk and Western), and throws. And misses. And misses again. But as the last car chugs by, he tries one more time: “BANG! Chuck smiled and raised his hands in victory.”

And this kind of persistence becomes emblematic of Chuck’s experience both in school and in football too, paving the way to his success as quarterback of the school football team. At games, he faces taunts from rival players because of the colour of his skin, but Chuck doesn’t let this break his focus from the object of the game, which is to connect with his teammates and win. And he does. The final words of the story: “Touchdown. Victory.”

The story is made all the more poignant with Richardson’s author’s note at the end of the book, which explains that Chuck Ealey won every game as quarterback of his high school team, and received a scholarship to the University of Toledo, where he won every game there. But after graduating with his college degree (“the best of all his victories”) he finds himself unable to play professional football in America, because the idea of a Black quarterback was still unfathomable to the powers that be.

So he moved to Canada, and played in the CFL, leading the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to the Grey Cup in his very first year. “It’s an unbeatable story that amazes me,” writes Richardson, “even though I’ve heard it all before, because Chuck Ealey happens to be my father.”

In Richardson’s Quill and Quire interview, Groundwood Books Publisher Sheila Barry underlines the need for more contemporary Black figures to inspire young kids: “We have Viola Desmond, but that was a long time ago.” Although obviously, this is a book that will appeal to readers regardless of the colour of their skin.

Together, Richardson and James have hit a target of their own: that of a really great story. And they totally nailed it.