January 31, 2016

Bearskin Diary, by Carol Daniels

Carol Daniels’ first novel, Bearskin Diary, is driven by a remarkable protagonist, powered by compelling narrative voice and an extraordinary point of view. Sandy Pelly was part of the “Sixties Scoop”, a First Nations child taken from her parents and set adrift in the fostering and adoption system. Her story, unlike so many others, turned out mostly well—she was adopted by white parents who were loving and supportive, who did their best to fight against the racism omnipresent in the society in which they lived, and she was well loved by her grandmother, her Ukrainian “Baba“, who instilled in Sandy a sense of her own self-worth and an instinct for story-telling. But the loss of her heritage and culture is deeply traumatic, a loss whose effects Sandy can’t even articulate properly—she doesn’t know what she’s missing. But she knows she’s missing something, not least of all a place where she belongs. There is a disturbing remembrance of Sandy at five-years-old trying to scrub away the brown from her skin.

Carol Daniels’ first novel, Bearskin Diary, is driven by a remarkable protagonist, powered by compelling narrative voice and an extraordinary point of view. Sandy Pelly was part of the “Sixties Scoop”, a First Nations child taken from her parents and set adrift in the fostering and adoption system. Her story, unlike so many others, turned out mostly well—she was adopted by white parents who were loving and supportive, who did their best to fight against the racism omnipresent in the society in which they lived, and she was well loved by her grandmother, her Ukrainian “Baba“, who instilled in Sandy a sense of her own self-worth and an instinct for story-telling. But the loss of her heritage and culture is deeply traumatic, a loss whose effects Sandy can’t even articulate properly—she doesn’t know what she’s missing. But she knows she’s missing something, not least of all a place where she belongs. There is a disturbing remembrance of Sandy at five-years-old trying to scrub away the brown from her skin.

Things are going well for Sandy. Against the odds, she’s making it as a TV reporter, a rare position for a First Nations woman in the 1980s (and not so common these days either)—and we’re shown the racism she has to contend with from co-workers. She and her best friend Ellen enjoy regular Girls Nights, and it’s at one of these that she meets Blue for the first time. A Metis police trainee, she is instantly attracted to him, for obvious reasons, but also because she sees a glimpse in him of what she’s missing in herself. Blue is similarly alienated from his culture, however, and their relationship proves complicated—she throws caution to the wind and decides to follow him to Saskatoon, where he lives and works, but after a period of domestic bliss, she realizes he’s still distracted by a previous relationship that might not be as far back in the past as she’d been lead to believe. While this revelation is devastating, however, Sandy has other preoccupations—she’s managed to find a great job in her new city, and has just received a troubling tip about Saskatoon police officers taking First Nations women into isolated areas and raping them, getting away with it over and over again. And as she’s grappling with just how to tell that particular story, Sandy is also connecting with local First Nations Elders and discovering the richness of a culture that’s been denied to her for her entire life.

I read the book in a couple of days, and found it fast-paced and really absorbing. Although I was compelled by the story itself and its main character, more so than the novel’s structure, the container that held it. While Sandy was a rich and textured character, secondary characters were more one-dimensional. There were also strange shifts in point-of-view throughout the text. But it also occurs to me that critiquing the book by English literature standards is also beside the point—Bearskin Diary is part of a different tradition and has a more mythological structure, with expansiveness instead of depth, with depth in the places that I didn’t look for it at first. It’s chronology too is remarkable, the present moment dissolving into the past—each one containing all those that came before. It’s a novel with the feel of the oral tradition—and indeed it’s the voice that draws the reader in.

Which makes reading Bearskin Diary really a pleasure. In a time in which it’s never been more important that First Nations’ women voices are heard (and read), Daniels’ novel is definitely one not to miss.

January 29, 2016

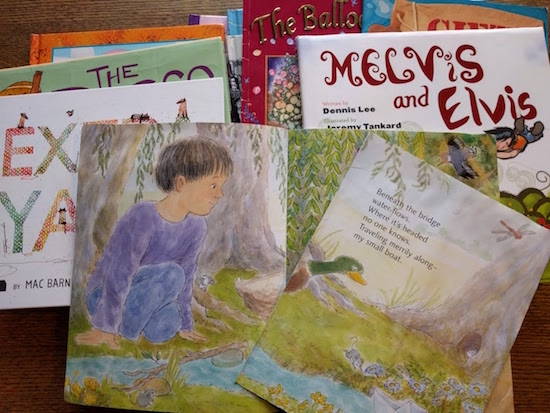

Picture Books We’ve Loved to Pieces

Wednesday was Family Literacy Day, and on 49thShelf, I wrote about the picture books our family has read to pieces. Reading with my children was been one of the most incredible parts of my life since they were born, and we’ve all come a long way since the first time I observed Family Literacy Day (which was six years ago, and I turned it into a week-long blogging extravaganza. Scroll down a bit here to se what we got up to). These days Harriet reads by herself more often than we read together, but we still read picture books every night, plus some of a chapter book—at the moment we’re doing The Borrowers Afield and it’s so perfect. Hanging out with books is my favourite way to be a family—or to be anything, for that matter…

January 28, 2016

Mitzi Bytes: An Outtake

The good news is that I handed in my edits today for Mitzi Bytes 4.0. The even better news is that it’s a much stronger manuscript than it was two weeks ago. The most substantial changes involved removing three blog posts (her blog posts, which are from her archives, come after each chapter of the main narrative, which is set in the present day). I liked these blog posts, but agreed that they didn’t serve to enhance the main story enough, so I wrote new ones that really do. Which left me with these outtakes, and thank goodness for the internet, which means they won’t have to go to waste. This particular post I read at the Draft Reading Series in November, and it went over pretty well, I think. It’s situated in the years before my protagonist meets her husband and settles down, during a time in which her tumultuous love life served as excellent blog fodder.

**

So it’s over. Good news for those of you who’ve been leaving comments haranguing me for being nauseatingly in love for the past seven weeks, for even counting the weeks. But come on, post-divorce, conducting a relationship for this length of time feels like an achievement. It’s an actual relationship. Seven weeks, at most times of the year, is a period long enough to include a statutory holiday and/or religious celebration. I met his mom. We had a pregnancy scare. This is the closest I’d come to forever since my marriage went down in sad and pitiful flames. And I see now how the whole thing was really just an experiment in intimacy, but in the midst of it, I thought I was writing the conclusion to the “Troubled” chapter of my life. That all my problems were solved.

But here we are right back where we started. And once again, the problem was me, and my compulsion to overlook other problems that are glaringly obvious. Once again, I really thought we’d find a way to make it work if I were just flexible and accommodating enough. Surely every relationship brings challenges and a couple is stronger for working through these. I really can’t believe there is a single bride who hasn’t lain awake on her wedding night beside a sleeping body and pondered whether she has possibly made a mistake.

Getting involved with D was never going to be a straightforward process—he was upfront about that from the start. He had strong ties to his mother and his sisters, and there was the matter of the son, G. G had been the result of a teenage fling, and he and his ex had worked hard to raise their son together, co-parenting and freeing him of any baggage that might come about from being someone who was conceived in the back of a pickup truck after a few too many drinks.

It helped too that the boy’s mother’s parents were loaded, ensuring that G. was well-looked after while his parents pursued their career goals, and from age six had been enrolled at one of the city’s most prestigious private schools. There would be no pick-up trucks for this upstanding young fellow whose achievements and admirable qualities his father was fond of reciting: the honour roll, valedictorian, vegetarian, peace activist, feminist, cycling advocate, chemistry whiz, philosophy buff, champion swimmer, hockey superstar and he packed boxes at the food bank at Christmas.

Obviously, he sounded insufferable, which was the first time since we’d met that I had a thought I couldn’t share with D, and that was awful. But in a way, I also feel sorry for the kid, because it must be hard to be talked-up like you’re a demi-god when you’re actually a thirteen-year-old boy, which is an awkward kind of person to have to be.

I finally met him last week. To be honest, I could have waited. I was completely okay with pretending this messianic child didn’t actually exist, even in spite of evidence to the contrary: his immaculate bedroom, some photos, a poster on the fridge from the march he’d organized in protest of the Iraq invasion. But none of these things made him real, which was fine with me, because a 13-year-old boy just didn’t seem like a thing my life was particularly missing.

But then one evening, there he was. He’d come down to D’s place after school, so he was wearing his school blazer whose crest was a mess of lions and swords. And even though he was as tall as I am, he was so clearly a child dressed up as a man that I was reminded of those old cereal commercials, the small boy dressed up in a big jacket at a big desk. But the boy took himself very seriously, firmly shaking my hand, sizing me up. “I’ve been hearing a lot about you,” he told me, as though he were the adult and I were the child. “Pleased to finally make your acquaintance.”

He had a moustache. I couldn’t stop looking at it. The most ridiculous thing on his pimply face. Dark and wispy, the moustache was no accident, it was cultivated, and I was reminded of lamb’s wool, of softness and down. Of a boy who’s trying to look like he’s not trying. The effort of being natural. Perhaps I should have identified.

But no, because I was actually trying to avoid natural at all costs. That night, natural would have betrayed me. So I kept a neutral expression as we had our dinner and he explained the ethics of veganism, of how it connected to the pro-life movement, and how he could be both pro-life and feminist at once. He was reading us the world as though it were something that existed in a sacred book we’d never heard of, and you got the sense that he was accustomed to other people being in awe of him, hanging on every word he said. His father was no exception.

“Isn’t he terrific?” D kept asking me after we’d seen G down the elevator on his way back to his mother’s. “I told you, didn’t I? That’s no ordinary kid.”

I managed to keep my mouth shut until we were at his sister’s the following weekend. D’s sister M, I imagined, was a woman after my own heart, completely lacking in pretention. It had been her pick-up truck that G had been conceived in. She still had the truck, and drove it up and down dirt roads in a cloud of dust. She wasn’t afraid to call things as she saw them. She’d already told me she was wary of a fresh divorcee in her baby brother’s life, but I appreciated her honesty. I would have been wary too.

So my guard was down as we sat out together on her veranda at the end of a busy day. The whole extended family was up there celebrating the long weekend, and they’d roasted a pig on a spit. Her own children were now running around the lawn with sparklers. We were each at either end of the hanging swing, legs curled up beneath us, cold bottles of beer in our hands. I thought I was looking in a mirror.

“So I hear you met the kid,” she said. He hadn’t come up with us, electing instead to stay in the city for a hockey tournament. D’s sister took a sip of her beer. “The little shit,” she said.

I waited a minute before I responded. “He’s certainly accomplished,” I offered.

“So he told you, I’m sure,” she said.

“His dad’s pretty proud.”

“He’s hoping the pride will override the guilt about everything else. It’s a mess,” she said. “And there’s no discipline. It’s better now, but you should have seen him when he was little. He got away with everything. They think the sun shines out of that kid’s ass.”

She started telling me stories, and we were still talking when the sparklers were burnt out, the sun set, and our bottles were empty. And up until this point, I’d handled myself with the utmost decorum—an especially impressive performance from the likes of me.

But then it all went wrong. We were sharing our impressions of wispy-lipped, pimple-face G, with his pro-life justice and the burgeoning build of a hockey enforcer.

I leaned in close, my voice low. I was really more than a bit drunk, though it’s still no excuse because I was speaking the truth. “The kind of kid,” I said, “who you just know is going to grow up to be a rapist. It’s practically written right there on his greasy forehead.”

D’s sister was staring at me now with a strange expression. I said, “Right?”

“I mean, maybe it was the blazer, or his teeth—that kind of orthodontia is a huge investment.” I was feeling vicious. I hated that kid. He was awful. “Shiny hair, and he’s just so convinced of himself. He was talking about his school, and he said, ‘They’re teaching us to be the leaders of tomorrow.’ He thinks he’s entitled to the whole fucking world.” But this hadn’t clarified things. “A little rapist,” I delivered finally, futilely. This was going over like a tumbleweed, and any rapport between us on the swing had disintegrated. She stood up and went inside without another word, leaving me swinging there alone.

I should have just found my car and driven back to the city, but I really was drunk, far too drunk to have found my car, let alone drive it. So I stayed in the swing until D found me there, coming in from where collecting fireflies with his nieces. They came up to the porch carrying jam jars full of dying light, and he left his on the rail so he could gather me up into his arms, and carry me upstairs to the bed in his sister’s spare room where we made love beneath a patchwork quilt that had been stitched by his great grandmother.

His sister didn’t get up in the morning. “Too much party,” everybody was saying, and my own aching head was pounding in agreement. D and I left after breakfast in order to the beat the traffic, which we didn’t beat, and I was quite sure that it was over then, as we sat there on the highway. He still had his eyes on the horizon, but I knew that everything between us was about to rapidly run out of gas.

She must have called him that night. I was at home still nursing my hangover with a pan frozen home fries, a fried egg cracked on top of them.

He texted me. “Did you call G ‘a little rapist’?”

I texted him back. “I can explain.”

One more time: “I’m not sure you can,” he wrote me.

And that’s the last I ever heard from him.

January 26, 2016

Funny Faces

Do you know that I’ve nearly filled up an entire notebook with jottings and quotes from my Mad Men rewatch, and we’re only just beginning Season Three? To what purpose, I don’t know. It’s my new fitness regimen (the Mad Men, not the notebooks) as I ride my exercise bike while we’re watching, and I check the time less and it goes by much faster than when I’m merely reading. (Don’t tell reading I said that; it’s all exercise’s fault anyway.) I might give up on fitness altogether at the end of Season 7. Anyway, it’s a scramble to get the children into bed so we can begin watching and me riding by 9 or so, which means when it’s over, it’s that time of day I’ve spent all day waiting for: time to curl up with Tana French. I am reading her novel, In the Woods, for the first time, and I am in reading heaven. Ostensibly crime fiction but so much more substantial than that, rich and enthralling. I am so busy right now, which was a terrible time to pick the book up, because all I want to read is read it all day and forever. I am looking forward to discovering her other four novels, each of which features a more minor characters from the previous. one Anyway, I’m now in the midst of my second week to finish up my edits on Mitzi Bytes, and things are going well. Getting back to it in a matter of minutes, but in the meantime, wanted to share with you some funny faces from previous days: Harriet and Iris and I making funny faces in the kitchen; evidence that Stuart and I indeed went skating at Harbourfront on Friday night and it was wonderful; and a perfect photo from yesterday when Iris broke into the stampers and rubbed one all over her face, inadvertently channelling David Bowie.

January 24, 2016

Busker, by Nisha Coleman

I picked up Nisha Coleman’s Busker on the recommendation of Isabel Huggan, so it wasn’t surprising that I loved it. It begins with Coleman, fresh out of university, following a man to Paris with romantic Parisian intentions, but the romance turns out to be more of an awkward misunderstanding. Leaving Coleman stuck in France without a visa, or money, or even a home, but what she does have is a violin. So she begins busking on the streets of Paris, and finds her way into the city through a kind of back door, and also finds a way into her truest self and the kind of life she wants to lead—a coming of age, of sorts. And from her perspective on the fringes—she’s in France illegally, busking itself is illegal in Paris although tolerated, and street performing is inherently fringey, sidewalks begin marginal as they are—she is able to tell a Paris story that’s very different from those we might have read before, those that are all Shakespeare and Company and Mavis Gallant. Busker is something different entire, a rich and generous portrayal of misfits and weirdos and the rhythms of urban life.

I picked up Nisha Coleman’s Busker on the recommendation of Isabel Huggan, so it wasn’t surprising that I loved it. It begins with Coleman, fresh out of university, following a man to Paris with romantic Parisian intentions, but the romance turns out to be more of an awkward misunderstanding. Leaving Coleman stuck in France without a visa, or money, or even a home, but what she does have is a violin. So she begins busking on the streets of Paris, and finds her way into the city through a kind of back door, and also finds a way into her truest self and the kind of life she wants to lead—a coming of age, of sorts. And from her perspective on the fringes—she’s in France illegally, busking itself is illegal in Paris although tolerated, and street performing is inherently fringey, sidewalks begin marginal as they are—she is able to tell a Paris story that’s very different from those we might have read before, those that are all Shakespeare and Company and Mavis Gallant. Busker is something different entire, a rich and generous portrayal of misfits and weirdos and the rhythms of urban life.

I kept laughing out loud, which is a mark of literary achievement. Though I also cringed—as one who has never mastered air-kisses, I recoiled at Coleman’s recounting of her first bisous and how she actually made cheek contact. She writes about being asked to play her violin in a hair salon, but how her own unruly do caused a great upset when she arrived. Or the man she met who wanted to perform songs he’d written, which turned out to be “sex songs” with lyrics like, “The horny bull wants a bouncy ride.” And she meets a lot of men, Coleman, and in the beginning, being lonely, takes them up on their invitations, until she realizes that she’s setting herself up for a lot of awkward interactions. She longs for the company of women friends as well, but these kind of relationships are harder to find. Not to mention that at the beginning of her time in Paris, Coleman hardly speaks French.

It is interesting to read a book about a character as solitary as Coleman is throughout much of the time she writes about. The stories she tells are of people she encounters, other characters who come and go, so there is little interpersonal development throughout the narrative. What sustains the narrative and brings all these stories together then is the development Coleman shows in her own character and understanding of it. She’d previously studied violin in university, but after suffering from performance anxiety she quit to do a major in psychology instead. Busking in Paris, however, Coleman finds her way back to the violin, and writes fascinatingly about how busking is not a performance, but about being part of a bigger scene. She writes compellingly too about the politics of street performance, scoping out prize spots, getting shut down by the police, engaging with other musicians and performers. About balance too—that her lifestyle is a kind of freedom and she’s brave to pursue it, but it’s also a method of avoidance: “I can’t fail at this because busking is an ongoing condition, not a means to an end.” And perhaps she gets a bit too comfortable in her Paris life, something that needs to be checked. “After all, Buscar is a Spanish word that means to search.”

What makes Busker so compelling is that Coleman is usually searching, is open to experience, and curious and wondering. She’s also funny, her prose is impeccable, and not she’s not afraid to make herself vulnerable in the narrative. Though it’s impossible could she ever hope to avoid seeming vulnerable in a book that begins with her in such a precarious situation, but the her faith in a city, its people, the world, pays off. In a time when we’re constantly being urged to harden ourselves against a cruel world, Coleman’s book reminds us of the miracles that can happen when we instead open up wide.

- Purchase Busker from McNally Robinson Booksellers

- Check out Coleman’s very cool companion to her book, Busker: The Interactive Experience

January 22, 2016

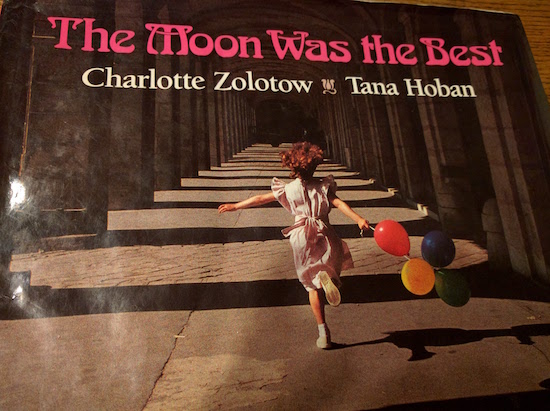

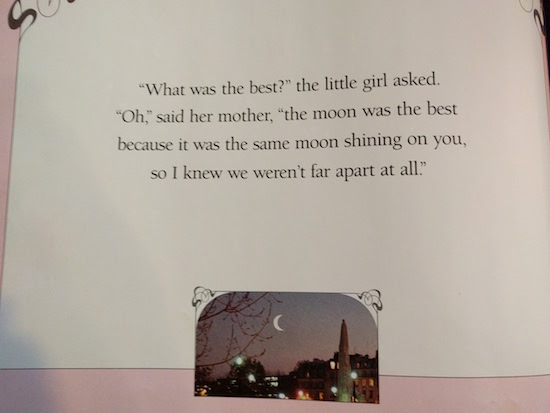

The Moon was the Best, by Charlotte Zolotow and Tana Hoban

I never knew that Charlotte Zolotow (literary legend, famous editor and author of books including William’s Doll, The Hating Book, and so so many others) worked with Tana Hoban, who was Russell’s sister and a photographer who produced beautiful children’s books throughout the 1970s and ’80s. But Harriet brought home this beautiful book from school yesterday, not a library book, a hardcover with its dust jacket intact. “What’s this?” I asked her, because she usually only brings home books about Scooby Doo. And she informed me that her teacher had loaned it to her. “I told her about the Barbados trip,” she said. “And she said I should read this.”

It’s a story about a little girl whose mother and father take a trip to Paris, and the little girl asks her mother to remember all the special things to tell her about. What the mother remembers isn’t necessarily what one would expect from a trip to Paris, but instead the memories are perfectly attuned to a child’s-eye view, gorgeously complemented by Hoban’s photographs in vivid colour.

You’ve probably heard me say before that Harriet has the most wonderful teacher, and the thing about such a statement is that it’s always been true. “The Barbados trip” is an event that looms large in Harriet’s future, our first time going away without her for a week, and while she’ll be in good care and is looking forward to many parts of having her adventures while we’re gone, she’s still nervous. Which her teacher was able to intuit, and treat with a literary salve—and what an exquisite one. I read the book twice, and its ending brought me to tears every time.

January 20, 2016

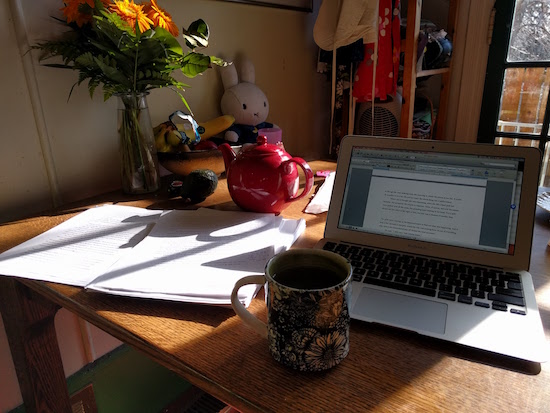

Editing Mitzi

I’m pretty well-acquainted with literary disappointment in all its forms, so don’t think that I’m delusional, but working on this book has never once been less than extraordinarily fun. Which is rare, I think, and I know I’m lucky, and lucky too to be working on something that people are waiting for, that I’m contractually obliged to produce—I can’t quite believe it. And during the mornings that Iris is at school for this week and next, it’s what I’m doing, putting together the latest (the final?) draft of Mitzi Bytes, the pressure on, not much time, and I’m loving it. That the thing in the world I most want to do is the thing in the world I most have to do—how often does that happen?

And it’s a pleasure too being edited—I love it. It occurred to me a few years ago while having an essay edited that having a great editor look at your work is like suddenly realizing that your house has entire wings you never even knew were there. My editor has made suggestions for this latest draft, and they seem so obvious to me now—of course that has to happen. It was always always meant to. I’d clearly intended it, all the scaffolding there, but just needed someone else to show me the way. The collaborative nature of it is so fantastic, and suggests how much of a book exists in its own right way outside of the mind of its writer—though if you’re a reader you already know that, that you are a creator too in this process. The whole thing is kind of a miracle. And it’s an amazing privilege to be creating right here on the front lines.

I finished my first draft just over a year ago (and have written two more since) and it’s exciting to consider how much has happened in that time. And even more exciting to think that in another year, this book will practically be an actual book. By then I’ll know what the cover looks like—seems impossible to behold.

January 17, 2016

Weekdays and ice rinks

Our first week back at school went so smoothly, and was such a relief after more than a month of illness and disruption, which meant, of course that week two was determined to thwart all that ease. Iris’s school was closed due to a broken furnace, Harriet’s school called at 9:45 on Monday morning asking her to be picked up because of an earache, and I’ve got all my usual work (49thShelf.com’s Spring previews don’t write themselves, you know!), plus revisions to my novel due in two weeks. Luckily, Iris’s school’s furnace found a temporary fix, Harriet’s earache was a passing fad, and we spent two days at home watching David Bowie on Youtube and playing in the snow—it all settles down. And there still seems to be time enough—perhaps because of all the stuff I’ve not yet got around to doing, but I’ll worry about that tomorrow (ha!). This winter we’ve ruined our lives by signing Harriet up for skating lessons on Saturdays and swimming lessons on Sundays, but there’s really no way around it because she has to learn both, but luckily lessons are close to home and we can walk there, and are either early or late enough in the mornings that we’ll get to do proper morning things (i.e. croissants and reading the paper). Yesterday we took her to her first skating lesson and she was amazing, and inspired us all to venture out skating today, which is the first time we’ve been skating for over two months. I haven’t felt up to it since having pneumonia, but today felt different. It didn’t hurt that all the snow has melted so hauling our stroller down Dufferin Street is no trouble and all, and also that it’s not cold outside so it’s a bit like skating in the spring. Such a pleasure, and of course there are hotdogs post-skate from the cafe, so that part is good too, and we all enjoyed it—except that Iris only enjoyed skating for half a lap, and then decided she’d only lie down on the ice and cry, so I had to drag her the rest of the way, and then the rest of her laps were taken from her stroller.

Our first week back at school went so smoothly, and was such a relief after more than a month of illness and disruption, which meant, of course that week two was determined to thwart all that ease. Iris’s school was closed due to a broken furnace, Harriet’s school called at 9:45 on Monday morning asking her to be picked up because of an earache, and I’ve got all my usual work (49thShelf.com’s Spring previews don’t write themselves, you know!), plus revisions to my novel due in two weeks. Luckily, Iris’s school’s furnace found a temporary fix, Harriet’s earache was a passing fad, and we spent two days at home watching David Bowie on Youtube and playing in the snow—it all settles down. And there still seems to be time enough—perhaps because of all the stuff I’ve not yet got around to doing, but I’ll worry about that tomorrow (ha!). This winter we’ve ruined our lives by signing Harriet up for skating lessons on Saturdays and swimming lessons on Sundays, but there’s really no way around it because she has to learn both, but luckily lessons are close to home and we can walk there, and are either early or late enough in the mornings that we’ll get to do proper morning things (i.e. croissants and reading the paper). Yesterday we took her to her first skating lesson and she was amazing, and inspired us all to venture out skating today, which is the first time we’ve been skating for over two months. I haven’t felt up to it since having pneumonia, but today felt different. It didn’t hurt that all the snow has melted so hauling our stroller down Dufferin Street is no trouble and all, and also that it’s not cold outside so it’s a bit like skating in the spring. Such a pleasure, and of course there are hotdogs post-skate from the cafe, so that part is good too, and we all enjoyed it—except that Iris only enjoyed skating for half a lap, and then decided she’d only lie down on the ice and cry, so I had to drag her the rest of the way, and then the rest of her laps were taken from her stroller.

You can see more of our mundane but colourful adventures over at Instagram: including our descent into pasta-making chaos, and my cranberry beef stew that nobody liked.

January 17, 2016

One Hit Wonders, by Patrick Warner

I added Patrick Warner’s novel, One Hit Wonders, to 49thShelf’s The Next Gone Girl list, a list of suspenseful novels about wives with secret lives. Because it belongs there for a few reasons—this is a novel with twists and turns, about a husband who discovers after his wife’s death that perhaps he didn’t know her at all, and it has the whodunnit element—who is responsible for the body lying on the floor? Suspects include her husband, Freddy, an antisocial novelist trying and failing to follow up his runaway hit first book whose proceeds he now easily lives off of; the has-been golf pro with whom Lila was having an affair and who had got her hooked on cocaine; and two small-time crooks who’d been caught up in a plan to rob Freddy of his millions. What makes this book different from the others though is Freddy’s unabashed complicity in its construction; it’s his second novel all along. But not a memoir—this is fiction. He’s creating conversations he never heard, imagining places he never went, and interactions he was never a part of in order to have the whole story make sense. Which makes us wonder if he’s complicit in other ways. Is there a truth to be uncovered at the bottom of all of this? And isn’t that we ask such a thing of fiction kind of an amazing thing?

I added Patrick Warner’s novel, One Hit Wonders, to 49thShelf’s The Next Gone Girl list, a list of suspenseful novels about wives with secret lives. Because it belongs there for a few reasons—this is a novel with twists and turns, about a husband who discovers after his wife’s death that perhaps he didn’t know her at all, and it has the whodunnit element—who is responsible for the body lying on the floor? Suspects include her husband, Freddy, an antisocial novelist trying and failing to follow up his runaway hit first book whose proceeds he now easily lives off of; the has-been golf pro with whom Lila was having an affair and who had got her hooked on cocaine; and two small-time crooks who’d been caught up in a plan to rob Freddy of his millions. What makes this book different from the others though is Freddy’s unabashed complicity in its construction; it’s his second novel all along. But not a memoir—this is fiction. He’s creating conversations he never heard, imagining places he never went, and interactions he was never a part of in order to have the whole story make sense. Which makes us wonder if he’s complicit in other ways. Is there a truth to be uncovered at the bottom of all of this? And isn’t that we ask such a thing of fiction kind of an amazing thing?

This is a novel about story-making, about empathy and where it can take us. Our own empathy—why is it that we long to get inside the heads of twisted people and be immersed in troubled lives—and also Freddy’s as he imagines himself into the minds of the men who orchestrated his wife’s downfall. He tells us, “I feel dirty after all that. And yet my task is to empathize with these characters, walk a mile in their shoes. The trouble is I have trouble with empathy. It seems to sit on the delusional end of the sympathy spectrum, perhaps at the point where sympathy runs out and something darker begins. Empathy is only a confidence trick, a species of legalese, a way of making the afflicted believe you are walking in their shoes. Empathy is the tool that gets you through the door. But who is to say what you will do once inside?”

And isn’t that passage wonderful? Warner is a wonderful prose writer, a critically acclaimed poet, and author of one previous novel, double talk, which was nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. And while One Hit Wonders might frustrate readers more interested in gritty realism than a look into fiction-building whose reality can fizzle out into nothing just when you think you can almost touch it, others will be most impressed at the genre-blurring metafictional achievement Warner pulls off here. I’m still not completely sold on the ending, but endings tend to be a bit like that, as Lila’s Freddy would attest.

January 15, 2016

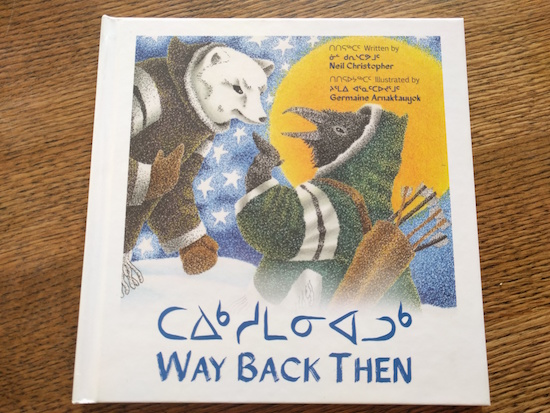

Way Back Then, by Neil Christopher and Germaine Anarktauyok

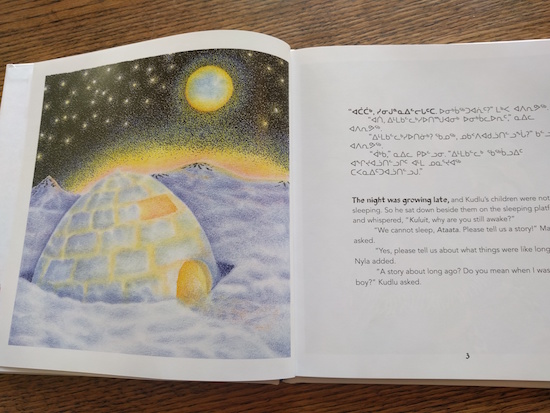

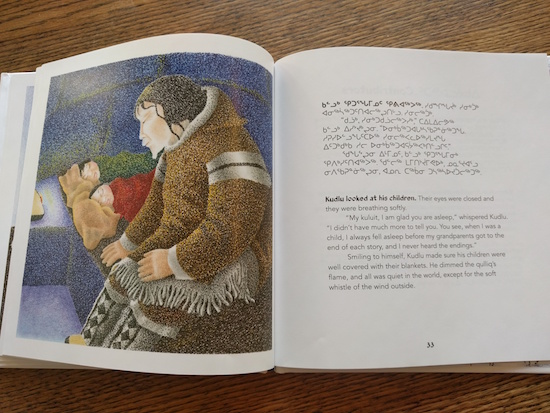

Our whole family really likes Way Back Then, by Neil Christopher and illustrated by Germaine Anarktauyok, a cozy northern story that takes place at night in a warm iglu as two children ask their father, Kudlu, to tell them stories of long ago. And not of so recently long ago either, stories of Kudlu’s boyhood, but instead tales of those times “when the mountains were giants and there was lots of magic in the world.”

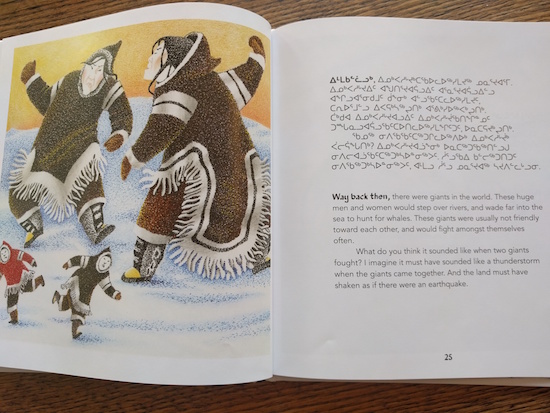

And so Kudlu proceeds to sketch out the legends he knows about why we have night and day, about how animals used to be able to remove their fur and feather like we take off our clothes, and also about how the caribou arrived when the land spirit cut a hole in the earth—but then the whole was accidentally left open and many caribou escaped and that’s why the North is filled with caribou.

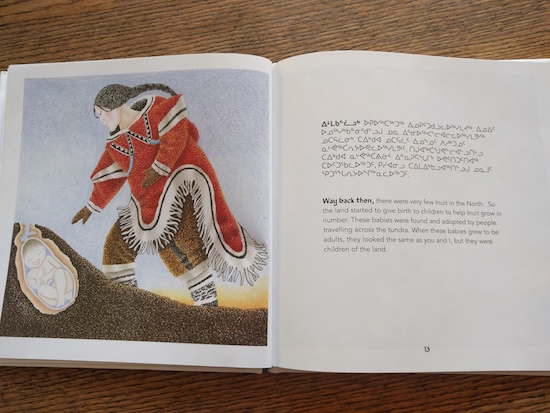

Illustrator Arnaktauyok is well-known for her paintings and prints that incorporate elements of traditional Inuit narratives. In the image above, the land is giving birth to babies in order for the Inuit to grow in number. “These babies were found and adopted by people travelling across the tundra. When these babies grew up to be adults, they looked the same as you and I, but they were children of the land.”

We are avid fans of fairy tales, and enthusiastically making our way through the Narnia series at the moment, which meant that these stories of tiny hunters and giants, talking animals and magic did not feel so otherworldly. The format of the stories too is engaging, the father telling these in the cozy night, children tucked up in their bed—perfect for when mine are just about to be so, even if we don’t live in an iglu ourselves. I also like the twist at the end—that Kudlu is relieved when the children finally go to sleep because he doesn’t know the endings of most of his stories, because he was always asleep himself by the time his grandparents got to those parts.

Inhabit Media is the only Inuit-owned publishing company in Canada’s north and they’ve become well established as makers of beautiful award-winning books that also serve to preserve Inuit culture. Written in both English and Inuktitut, the book also includes an Inuktitut pronunciation guide for terms that appear in the former—ataata (“a-ta-ta”) for Father; kuluit (“koo-loo-eet”), a term of endearment meaning “dear ones.”

And check out the caribou endpapers—this is a great book from start to finish.