September 14, 2015

Martin John, by Anakana Schofield

“That’s aggressive, but you see this hasn’t been an easy book for any of us.”

“That’s aggressive, but you see this hasn’t been an easy book for any of us.”

Anakana Schofield’s Martin John, a novel about a sexual deviant and the follow-up to her award-winning Malarky, is primarily a book about language. It’s about sexual violence is able to happen because of words and ideas that are never articulated or defined, and how these ellipses in our understanding go on to create further damage and harm. “It was a time when people didn’t ask as many questions. That’s the time it was.”

And so in order to fill in the blank, to ask the questions, to define the it, Schofield has to reinvent the shape of a novel. Eschewing chronology, point-of-view, objectivity, artifice itself for something that more resembles a case study, a long-form incident report. Just the latest for Martin John, the reader supposes, who has been in and out of the care of psychologists, social workers and other medical professionals for much of his life. Though he makes a point to stay out of their way—meddlers—and to keep to his routines, essential. He’s holding down a job as a security guard, lives in a nondescript shabby house in London (albeit one cluttered with the detritus of his media habits), visits his Aunt Noanie on Wednesdays, under specific instruction of his mother back in Ireland. (D’ya hear me, Martin John?) But it’s clear that, no matter his circuits and refrains, this centre (a precarious arrangement orchestrated by the mother) simply cannot hold.

The Mother. Martin John’s mother is a spiritual sister to Our Woman from Malarky, who does make an appearance in this latest book, encountering Martin John in a psychiatric ward. (You might remember him as “Beirut”.) Both women are undone by motherhood, wielding teapots as weapons, this action underlining their powerlessness. And yet. Are they really powerless? Are they bad mothers? Do they do what they do out of love? Or what? Do we blame the mother? Does it even matter? Does being a mother somehow put a woman beyond reproach?

Do we blame the mother? The collective address here is not rhetorical. I’m talking to you, and Schofield’s narrator is talking to all of us:

“She did not the idea she had a role in it.

You would not like the idea you had a role in it.

Did she have a role in it?

Have you had a role in it?

Do you have a role in this?”

Martin John forces the reader to be held accountable for some of the violence contained therein, for that time it was in which people didn’t ask as many questions is happening right now. “A thesaurus of vagueness for remembering,” Schofield writes. Think of a now-infamous CBC presenter, hmm? All this making for a discomforting read, made even more so, remarkably, by the reading not being so discomforting at all.

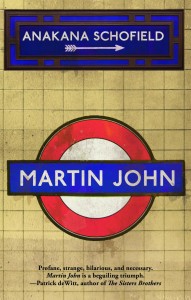

For a novel about a sexual deviant, Martin John is positively breezy. It’s humorous in places, fast-paced, its momentum spurred on by the arrows separating the text’s sections, part of the book’s overall transit motif. A motif that’s important to understanding the book as a whole, notions of underground and close proximity, of public, that these are people who live among us—they are us. And what are to do about that? The idea of transit and transit maps connecting to Martin John’s behaviour too, his loops and circuits. A sense of inevitability. The way that one thing leads to another: “Strange. Estranged. Estuary ranged.” It all comes back to words again, connections, missed or otherwise.

As Anakana Schofield is a friend of mine, I perhaps cannot be relied for a wholly objective review of her work, those it pleases me immensely that I don’t have to be. Read a rave review (one of many) from the Globe and Mail this weekend, and celebrate Martin John’s deserved appearance on the Scotiabank Giller longlist.