August 16, 2015

This is Happy, by Camilla Gibb

While it is certainly true, as Joan Didion wrote, that we tell ourselves stories in order to live, it is possible that by now the phrase itself has become so hackneyed as to be a cliche, as have become gushing publisher’s copy comparing heartbreaking memoirs to Didion’s A Year of Magical Thinking. But while the good people at Doubleday Canada have resisted to the temptation to slap Camilla Gibb’s memoir, This Is Happy, with the Magical Thinking comparison, I think this the rare case in which the comparison really does apply—Gibb’s memoir is a no-holds-barred dispatch about devastating heartbreak from the frontiers of stark grief, a gut-wrenching story told from the perspective of a most cool and discerning “I”. It’s the “telling ourselves stories in order to live” in practice, Gibb, like Didion, pasting the pieces of her shattered life together, the art that emerges from the exercise.

While it is certainly true, as Joan Didion wrote, that we tell ourselves stories in order to live, it is possible that by now the phrase itself has become so hackneyed as to be a cliche, as have become gushing publisher’s copy comparing heartbreaking memoirs to Didion’s A Year of Magical Thinking. But while the good people at Doubleday Canada have resisted to the temptation to slap Camilla Gibb’s memoir, This Is Happy, with the Magical Thinking comparison, I think this the rare case in which the comparison really does apply—Gibb’s memoir is a no-holds-barred dispatch about devastating heartbreak from the frontiers of stark grief, a gut-wrenching story told from the perspective of a most cool and discerning “I”. It’s the “telling ourselves stories in order to live” in practice, Gibb, like Didion, pasting the pieces of her shattered life together, the art that emerges from the exercise.

For anyone familiar with Gibb’s fiction, much the memoir will be familiar too, so much of the former rich with autobiographical details, her first two novels in particular. It is clear that Gibb has been telling herself stories in order to live since her success with her first book in 1999, Mouthing the Words, which was also the story of a young girl from a broken home with a troubled father and plenty of trauma, mental illness, and the disillusionment of the Oxford experience. In This is Happy, Gibb goes back to her own beginnings to paint a picture of her early struggles, trying to pinpoint the moment where it all went wrong.

The happy ending was supposed to be Gibb’s marriage, which lasted ten years, to a woman who is called “Anna” in the book. A period of calm, of happiness. She does not slip into depression, she writes, she finds continued literary success. And then in her late thirties, she is surprised by a yearning to have a baby. After a painful miscarriage (though I don’t know there is any other kind), Gibb finds herself pregnant again, still tentatively so—just eight weeks along. When Anna reveals that their relationship is over, that she has fallen out of love with her. Sending Gibb into torrents of grief, which is extra-troubling because of the new life she carries inside her: this was supposed to be a beginning. Instead it’s more of the same, and Gibb fears her child growing up with the same hardships, emotional deprivations, and sense of displacement that plagued her throughout her own childhood. The damage is being done already, she feels, knowing how a fetus is meant to be affected by a mother’s stress. And she is powerless to stop it.

Except that she isn’t, which is the miracle of narrative. That it moves forward, even if one is only crawling in agony. The final third of the book is the story of Gibb’s pregnancy and experience of new motherhood, and it’s not clear for a long time that this will be a story of triumph. For most of this period, Gibb is wracked with despair, receiving special care after the baby arrives—she realizes later—not because her midwife has concerns about lactation, but because she is crying all the time. Gibb resisting a diagnosis of depression in a way I find interesting, because felt similarly when I first became a mother: that this is not depression, it just that life is terrible. Except that for Gibb, returning to antidepressants brings with it some relief. As does the support system that she has built around her as she’s put her life back together again.

In the new home that she has made for herself and her daughter, Gibb is surrounded by her long-estranged bother, an addict struggling to overcome his demons; her nanny, Tita, an immigrant from the Philippines who is waiting to be able to bring her husband to Canada to be with her; as well as friends, but not the ones she might have expected. Her brother builds her a back deck and does home renovations, she and Tita embark upon the complicated dance of an employer and employee who become much more than that. When her daughter is just a few weeks old, Gibb takes her across the country on tour for her novel, The Beauty of Humanity movement, revealing little of her pain in media interviews, though to be fair, most new mothers only ever really understand the mess they were in in retrospect anyway.

It is not a convenient trajectory: this unconventional family arrangement is not the ending either, but a moment in time. Gibb’s brother eventually leaves for Vancouver, his period of sobriety ending; Tita’s husband arrives, and they’re going to need space to become a family of their own. Gibb’s daughter gets older, a little person in her own right. Every resolution brings with it another kind of challenge, but eventually—with the help of her psychoanalyst, her unique support network, and a lot of what she’s learned about herself in the stories she’s told herself in order to live and then interrogated in order to see deeper—she finds some kind of footing:

“This is the circle that could never quite be complete… It is a story with a different ending. A story without an ending at all./ And this, I know, is happy.”

The amazing but necessary understatement of the final statement. Happiness being only an ordinary thing. And it is, and yet one must undergo a certain amount of experience before understanding that there is nothing ordinary about it—Joan Didion wrote about that in Blue Nights.

While Gibb’s own story is harrowing and awful, it emerges not as the most remarkable element of the memoir, which is instead her narrative voice, the “I” that is Didionesque. Not in the rhythms and cadence, for Gibb’s prose is excellent and entirely her own, but in the distance, the coolness, and restraint. The reader is not to imagine herself in Gibb’s shoes on that fateful day when everything changed, when she’d just purchased a freezer full of expensive fish, anticipating dinner parties and occasions unrolling into the future like a ribbon. She gives a sense of what it felt like, but that sense is not the point: the point is what does it mean? What does one make out of this kind of devastation?

And in Gibb’s case, with This is Happy, the answer is a beautiful, powerful book.

August 13, 2015

Three New Books About Loss

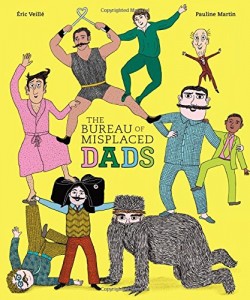

The Bureau of Misplaced Dads, by Eric Veille and Pauline Martin

The Bureau of Misplaced Dads, by Eric Veille and Pauline Martin

This book has a vintage vibe right down to its oranges, greens and yellows, the crosshatching, and that the illustrations remind me so much of Esphyr Slobodkina’s Caps for Sale—perhaps it’s the moustaches? It also is completely weird in that way picture books got away with back in the day. Utterly pointless, silly, absurd, and I mean it in the best way. (Maybe it’s just European?) It’s about a boy who loses his dad one morning and finds assistance at the Bureau of Misplaced Dads, where lost fathers go to wait for their children to retrieve them. (Most are in fairly good condition when they’re finally found.) Some are found same day, others have been waiting since the dawn of time. “The dads in striped sweaters hang out in the Ping-Pong room.” They aren’t allowed to play with the crocodiles, but otherwise they can do anything they please. There are two full-page spreads that are totally Wild Rumpus-inspired. The ending will satisfy anxious readers, but is just as strange as rest of it, which is to say that it involves a short cut in which the boy climbs up the ladder beside an old dog, and arrives home via a hole in the floor. Hooray for short-cuts, and books rich with strange surprises.

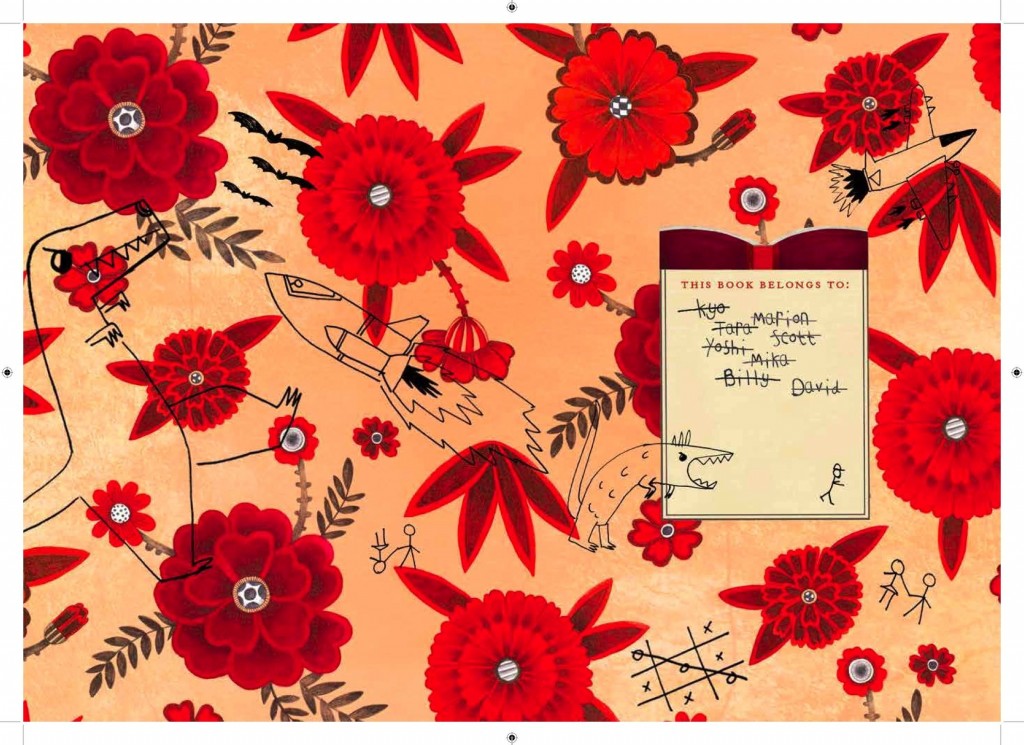

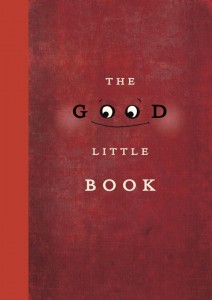

The Good Little Book, by Kyo Maclear and Marion Arbona

The Good Little Book, by Kyo Maclear and Marion Arbona

I was rhapsodizing about Kyo Maclear a couple of weeks back because she’s managed to have two books out this fall that are very different and both excellent—she’s so good! The Good Little Book is a gorgeous package, its deliberate graffiti’d bookplate and endpapers, the whole thing beautifully designed to emphasize the book as object, which connects to the story. About one book in particular that is “neither thick nor thin, popular nor unpopular. It had no shiny medals to boast of. It didn’t even own a proper jacket.” (Get it? Jacket?) But this little book finds its way into one reader’s heart, and there it stays, accompanying the reader everywhere, changing his life. Until one day the book gets lost. The boy who lost it fearing for his book in the wild, seeing as it doesn’t even have a jacket. (Ha!) But a good book, the boy learns, never really goes away, and the book itself, we learn, continues to be loved and read, as good books do. “Is this the end of the book?” is the question inked upon the final pretty floral endpaper, to which this reader knows the answer: never!

Some Things I’ve Lost, by Cybele Young

Some Things I’ve Lost, by Cybele Young

As one who has long been intrigued by the secret lives of things, I’m intrigued by Cybele Young’s new book, which is inspired by her paper sculptures. A set of keys, a roller skate, an umbrella (and I do have a fascination with literary lost umbrellas), a pair of glasses. Things that disappear (and I’ve written about that too). But: “Where there’s an end there’s a beginning,” Young’s book’s introduction tells us. “Things grow. Things change.” The books’ transformations are abstract enough as to be unpredictable and engaging, and budding artists might be inspired to make their own “some things” new.

August 11, 2015

Sistering by Jennifer Quist

It would have saved me a whole lot of trouble if Sistering, by Jennifer Quist, had had a different cover. Something pink and quirky, a decorative font, I’m thinking a pair of legs sticking out of an open grave, feet in sparkly slippers. Instead of the sombre cover the book has now, which had me imagining I was reading something deep and serious. Although the actual cover did appeal to me too—stair steps like siblings, one after the other. This was a book about five sisters, the copy told me, which put me in mind of the early ’90s melodrama Sisters starring Sela Ward and (for a season) an early George Clooney, which I was totally obsessed with when I was 12. But Sistering was more Mary Hartman than Sisters, a morbid comedy. A romp, like the cover copy says, even though there is nothing rompish about the cover image as it stands.

It would have saved me a whole lot of trouble if Sistering, by Jennifer Quist, had had a different cover. Something pink and quirky, a decorative font, I’m thinking a pair of legs sticking out of an open grave, feet in sparkly slippers. Instead of the sombre cover the book has now, which had me imagining I was reading something deep and serious. Although the actual cover did appeal to me too—stair steps like siblings, one after the other. This was a book about five sisters, the copy told me, which put me in mind of the early ’90s melodrama Sisters starring Sela Ward and (for a season) an early George Clooney, which I was totally obsessed with when I was 12. But Sistering was more Mary Hartman than Sisters, a morbid comedy. A romp, like the cover copy says, even though there is nothing rompish about the cover image as it stands.

Which meant that I was confused at the beginning of the book by the strangeness of the characters, by their unnatural behaviour, and how nobody ever remarked on it. Although the story was compelling, and the writing was good, but I kept getting caught on certain points—how Suzanne is obsessed with her mother-in-law, for one. An affliction that’s happened to no one that I’ve ever known, but her sisters take it for granted. And then things with Suzanne and her mother-in-law take a particularly weird turn when the mother-in-law dies in an accident in her home, and Suzanne responds in a way that is, um, untraditional to say the least. At this point I was still not fully cognizant of the constructs of Quist’s literary universe—confused by the cover—and so the absurdity of the situation just seemed bizarre. Until I read further (compelling story, good writing, remember?) and realized that absurdity was the very point.

Quist is no stranger to odd books about death. Her first novel, Love Letters of the Angels of Death, was completely unique and well received, though with a twist at the end that I could not bring myself to bear for personal reasons, and so I was unable to fully appreciate it. This second book has a lighter touch, but with the same morbid preoccupations—one sister runs a funeral home, another mimes her own mother-in-law’s suicide, and another owns a shop creating cemetery monuments. Both books daring to present death as part of every day life, worth writing a romp about even. And in the end, the morbidness comes to takes a back seat to the sisters themselves, who were never meant to be ordinary or “relatable” in the first place—although they’re all familiar in many ways. Sometimes scarily so.

Over the course of the novel, Suzanne loses her mother-in-law, two of the other sisters find theirs are resurrected, babies are born, marriages are broken, so is an engagement, and there is a whole lot of gossip in the meantime under the guise of concern. That the sisters and their husbands are more types than fully realized characters is part of the exercise, as to exist in a large family is to be typecast—how else is one suppose to carve out her place? The types themselves setting up the potential for absurdity as characters behave accordingly. When nobody is just ordinary, neither is the plot.

I liked this book—though it took me some time to be sure about this, because for nearly the first half, I was mostly just confused. But once I figured it out—it’s supposed to be funny—it really was. Weird and original, a dark comedy indeed—not necessarily miles away from Sela Ward and Sisters either. This one that will appeal in particular to readers who loved Trevor Cole’s Practical Jean, and to anyone who ever had a pack of sisters.

August 9, 2015

I wish there was more

We didn’t need clocks on our vacation, or calendars. The hours of the day were accounted for by the sunshine as it moved across the grass, and we had to move the hammock to keep up and remain in the shade. The days themselves were marked by the the spread of a rash down my arms, which became quite extensive because the weather was great and we were swimming every day and I am actually allergic to lake water. It’s hard out there for a sex-goddess. Anyway, the week progressed as quickly as the rash did. I read seven books, this success jump-started by our rental car pick-up being delayed and so I got to sit for 1.5 hours reading Nora Ephron’s Heartburn before we even hit the road. It was wonderful, and contains the delicious recipe for Potatoes Anna which I have since made twice. I will be writing more about my vacation reads soon.

Our week away was lunches, cruising down highway to the strains of Taylor Swift, corn on the cob, watching boats, eating butter tarts and creamsicles, playing UNO, digging holes, building castles, making smores in the oven, going out for Kawartha Dairy Ice Cream, and reading Mary Poppins. Iris was impossible and so frustratingly two that sometimes the whole endeavour was too exhausting to be vacation, but it all came together in the end, even if the morning sounds of birds outside woke her up far earlier than we would have liked. I particularly enjoyed reading vintage Archie digests and doing the pie shack shimmy (see photo above).

We came home a week ago, and spent a fun long weekend in the city hanging out with our friends. I’ve been reading some terrific new books I’m excited to be able to share with you, and trying to get work done on a big project I’m looking forward to sharing with you soon—although Iris wasn’t sleeping well at all, which has put a cramp on my “working in the evening” plans. Further cramping has ensued since my swimming rash morphed into an insane reaction this weekend, colonizing my face, which is now swollen and gross. So I am not only hideous, itchy and uncomfortable, but was prescribed super hardcore antihistamines at a walk-in clinic this morning that have rendered me totally stupid. It is possible that I’ve written this entire post in Latin, and I don’t even realize. Veni. Vidi. Itchi.

**

Dermatological issues aside, my only real complaint about summer is that it’s half-done. A splendid one so far. This weekend well-spent even through the rashy trauma as I compulsively read Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, which I absolutely had to purchase used after reading Rohan Maitzen’s post about it. She writes, “If you ever read a book, or were a child, or read a book to a child–if your childhood was shaped in any way by the books you read–then you should buy this book and read it immediately.” It’s the best advice I’ve followed in ages, and I’d urge you to do the same. Certainly a window into the mind of the woman behind literary classics such as Where the Wild Things Are, Harriet the Spy, Good Night Moon, Charlotte’s Web, The Carrot Seed, Harold the Purple Crayon, and others. 500 pages and I read it in three days. I wish there was more.

Dermatological issues aside, my only real complaint about summer is that it’s half-done. A splendid one so far. This weekend well-spent even through the rashy trauma as I compulsively read Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, which I absolutely had to purchase used after reading Rohan Maitzen’s post about it. She writes, “If you ever read a book, or were a child, or read a book to a child–if your childhood was shaped in any way by the books you read–then you should buy this book and read it immediately.” It’s the best advice I’ve followed in ages, and I’d urge you to do the same. Certainly a window into the mind of the woman behind literary classics such as Where the Wild Things Are, Harriet the Spy, Good Night Moon, Charlotte’s Web, The Carrot Seed, Harold the Purple Crayon, and others. 500 pages and I read it in three days. I wish there was more.