July 12, 2015

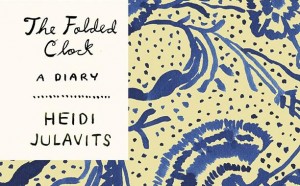

The Folded Clock: A Diary by Heidi Julavits

On Monday evening, I became overwhelmed by an irrational compulsion to go out and purchase a copy of Heidi Julavits’ new book, The Folded Clock: A Diary. Like I really needed another book, but there was something about this one—I’d been reading about it at edge of evening over the past month or so—and I not only had a car (I was visiting my parents in Peterborough where the chain bookstore is open late) but I had no one sensible to talk me out of an out-of-the-way jaunt to the bookstore past the children’s bedtime, so we went and I am so glad we did. It would be a shame if my totally irrational compulsion purchase turned to be disappointing, but it was amazing, mind-blowing. I read it once and then went through it again in my hammock yesterday, making notes, trying to figure the whole thing out. It doesn’t hurt that the cover designer is Leanne Shapton, though the only bad thing about that is that the cover got damaged in my bag and now I am a little bit devastated.

On Monday evening, I became overwhelmed by an irrational compulsion to go out and purchase a copy of Heidi Julavits’ new book, The Folded Clock: A Diary. Like I really needed another book, but there was something about this one—I’d been reading about it at edge of evening over the past month or so—and I not only had a car (I was visiting my parents in Peterborough where the chain bookstore is open late) but I had no one sensible to talk me out of an out-of-the-way jaunt to the bookstore past the children’s bedtime, so we went and I am so glad we did. It would be a shame if my totally irrational compulsion purchase turned to be disappointing, but it was amazing, mind-blowing. I read it once and then went through it again in my hammock yesterday, making notes, trying to figure the whole thing out. It doesn’t hurt that the cover designer is Leanne Shapton, though the only bad thing about that is that the cover got damaged in my bag and now I am a little bit devastated.

- Read Eula Biss’s New York Times review of The Folded Clock

- Read Heidi Julavits’ tumblr, The Keeping Society: Objects and Ephemera from The Folded Clock

The Folded Clock is a diary, though it’s a most peculiar diary. Chronology is jettisoned in favour of an arrangement of time that is and isn’t wholly random. A year’s worth of entries, each one beginning with, “Today I…” The book’s inspiration, Julavits writes, coming from an experience she had revisiting the diaries of her young, writing that she’d always imagined was her foundation as a writer, and finding instead of a foundation that, “The actual diaries revealed me to possess the mind of a paranoid tax auditor.” Time itself, she notes, had changed, becoming sweeping, a simple day insubstantial. She’d also recently borne a serious illness, one that challenged her perceptions of time: “It was no longer linear; it did not cut through my day like a road. I did not see time ahead of me. I experienced time on top of me.”

Time is a preoccupation of the entries in The Folded Clock, as evidenced by the title. Time itself not linear—many of the “Today I…” entries are actually about events decades-old, inspired by objects or experiences in the present day—and there is the issue of the construction of the book itself, which was deeply revised and shaped over another period of time divorced from the immediacy of the diary. Parenthood is another preoccupation connected to time—the impossibly tiny span of a childhood, which spins out of our control, and then conversely (but not really), the unbearable vastness of time in a child’s company: “how can this day not mostly involve my waiting for it to be over?”

Time is a preoccupation of the entries in The Folded Clock, as evidenced by the title. Time itself not linear—many of the “Today I…” entries are actually about events decades-old, inspired by objects or experiences in the present day—and there is the issue of the construction of the book itself, which was deeply revised and shaped over another period of time divorced from the immediacy of the diary. Parenthood is another preoccupation connected to time—the impossibly tiny span of a childhood, which spins out of our control, and then conversely (but not really), the unbearable vastness of time in a child’s company: “how can this day not mostly involve my waiting for it to be over?”

The diary’s various settings become familiar—the writer’s apartment in New York City, the community in Maine where Julavits, her husband and their children spend their summers, the German villa where they’re living while her husband is on a fellowship, and various artist retreats to which she escapes throughout the year. There is nothing haphazard in the entries’ arrangement, so that we’re introduced to a concept or thing or incident and will be referenced later, our knowledge taken for granted. Less obviously, the entries seem contextualized from a future vantage point so that each one takes its reader somewhere—a mini-essay every one. There is cohesion to the entire project, though the patterns are difficult to discern. Which is the point, Julavits points out, in one of the several clues she offers throughout the book pertaining to its curious construction:

“What’s on the page appears to have busted out of my head and traveled down my arms and through my fingers and my keyboard and coalesced on the screen. But it didn’t happen like that; it never happens like that.”

The Folded Clock is a book about the puzzles and mysteries of an ordinary comfortable life. For me, one of those mysteries is the way that a book—an object wholly apart from my existence, until I bought it—can appear to be reading my mind, stealing my life. (I have this experience also when I am reading Rebecca Solnit.) Like Julavits’ whole chapter about Wasted: The Preppie Murder, by Linda Wolfe, and being three fucks away from Robert Chambers—not that I have ever been such a thing, but I have a thing about that book. Or about abortions as women’s work, about how the boyfriends are always informed but they’re never there—abortions are something that happen between friends. About the internet and desire, about conscious attempts to resist the google-ization of everything—which is interesting because there is at first glance something so bloggish about Julavits’ approach, and yet the construction of her entries is so counter to blogging’s immediacy. The Folded Clock is a bit of a throwback, a project decidedly analogue.

It works because the writing is wonderful: lines like, “Worrying about originality is like worrying about the best place to hang your wall phone.” Anecdotes that start with, “Once I stole the name of a fetus.” How could you not want to read the rest? And while her prose style isn’t Didion’s, Julavits has that writer’s ability to lay down a thread and appear to be following it, while she is in fact blazing an altogether different trail. Connections, symbioses, and coincidence—all interwoven, meaningful and nothing by the by. And always, unfailingly, interesting. The question of whether male writers ever consider female writers a threat. The nature of relationships. Some of these entries made me uncomfortable, sometimes because I couldn’t identify, and other times because I could. And any diary worth its salt should garner such a response.

I loved this weird wonderful beautiful book, a book that was also easy to read in little bits—important when I was caring for my children without a break last week. A book I knew I needed before I needed it, and there is something otherworldly about the whole thing. Or perhaps I mean the opposite, that the book—with its preoccupation with objects and thingness and remarkable beauty as a thing itself—is eerily all too wordly—but then its not, it’s so rarefied, no matter how much it seems to have busted out of a head, out of the earth.

But still, it’s the kind of object one wants to go around clutching. Last week I wrote down directions to my friend’s house on a yellow post-it note that I promptly lost, mysteriously—which is another of Julavits’ preoccupations, the way that an object can dematerialize. When I found the post-it note again yesterday between the end pages and the back cover, I was not at all surprised. And I left it there. I will discover it again the next time I read the book, and of course I will remember.

I definitely want to read it now. That post-it note was between two pages towards the back when I saw it. Clearly has a mind of its own.

You will love it, I think. It’s a bit like what the Jenny Offill book was reaching at, but more substantial.

Lovely review. So glad you enjoyed it! And that cover — it really does look amazing wherever you put it down. Have you listened to Heidi Julavits talking about the genesis of her diary on the Lit Up Show podcast? Really interesting.

I will listen tonight while washing the dishes!!