June 16, 2015

Making the world more beautiful…

Speaking of Miss Rumphius, we’ve been lucky enough to find a way to make the world a more beautiful place this summer. We live in one of those annoying (if you’re driving and want to get anywhere quickly) downtown neighbourhoods—literally a five-minute walk from where Jane Jacobs lived—in which the streets only partway belong to cars, and a one-way system has turned side streets into a maze. The one-way streets are indicated by concrete planters that block access to the road, but which haven’t been maintained regularly so that more than a few of them have been filled with weeds and garbage in recent years. Until this year, however, when the neighbourhood residents association went looking for people to “adopt” planters, and we volunteered. We didn’t even have to do the hard work. Another neighbour dug up the weeds, filled the planter with new compost, and planted a shrub.

Speaking of Miss Rumphius, we’ve been lucky enough to find a way to make the world a more beautiful place this summer. We live in one of those annoying (if you’re driving and want to get anywhere quickly) downtown neighbourhoods—literally a five-minute walk from where Jane Jacobs lived—in which the streets only partway belong to cars, and a one-way system has turned side streets into a maze. The one-way streets are indicated by concrete planters that block access to the road, but which haven’t been maintained regularly so that more than a few of them have been filled with weeds and garbage in recent years. Until this year, however, when the neighbourhood residents association went looking for people to “adopt” planters, and we volunteered. We didn’t even have to do the hard work. Another neighbour dug up the weeds, filled the planter with new compost, and planted a shrub.

And then it was over to us, and one day in May we planted alyssum and two lavender plants. We probably should have been more strategic and creative about what to plant, but we were keen and impulsive, so went for it. Happily, the flowers have spread and the garden is lovely now, and when we walk by on our way to school every day, our children bid the planter, “Good morning!” Every evening after dinner we head down the street with our watering cans and give the plants their drink.

There is also now a palm plant in the garden that looks strange and out of place. One day I arrived to water the planter, and someone had left it there for us, quite deliberately, it seemed, the bulb nicely preserved. Now, I’ve heard of people stealing plants from gardens but not so much anonymously bestowing them, and so in order to encourage such behaviour I planted the bulb. Community spirit and everything. I don’t know who gave it to us (or what the plant is!), but I do know that taking care of our planter has connected us with our neighbours in the most fantastic way. We’ve met people out-and-about while we’ve been watering, and heard from others who appreciate the cleaned-up planter and have volunteered to do the watering while we’re on vacation this summer.

There is also now a palm plant in the garden that looks strange and out of place. One day I arrived to water the planter, and someone had left it there for us, quite deliberately, it seemed, the bulb nicely preserved. Now, I’ve heard of people stealing plants from gardens but not so much anonymously bestowing them, and so in order to encourage such behaviour I planted the bulb. Community spirit and everything. I don’t know who gave it to us (or what the plant is!), but I do know that taking care of our planter has connected us with our neighbours in the most fantastic way. We’ve met people out-and-about while we’ve been watering, and heard from others who appreciate the cleaned-up planter and have volunteered to do the watering while we’re on vacation this summer.

It’s only June, but we’ve already got a best-part-of-our-summer-so-far. We really can’t walk past our planter without Iris sticking her nose into the lavender. It’s just about that point in the season where nature explodes with fecundity, so we’ve got weeding to do and the flowers are spreading fast. And I love that this experience is teaching my children about community involvement, how gardening can be revolutionary, about simple biology, and they’re learning responsibility too—which is important because we’re never ever getting a pet (no way!). They don’t even feel ripped off (yet) that instead of a pet, they’ve got a concrete box that stops traffic, but of course it’s so much more than that, as Jane Jacobs herself would attest.

It’s only June, but we’ve already got a best-part-of-our-summer-so-far. We really can’t walk past our planter without Iris sticking her nose into the lavender. It’s just about that point in the season where nature explodes with fecundity, so we’ve got weeding to do and the flowers are spreading fast. And I love that this experience is teaching my children about community involvement, how gardening can be revolutionary, about simple biology, and they’re learning responsibility too—which is important because we’re never ever getting a pet (no way!). They don’t even feel ripped off (yet) that instead of a pet, they’ve got a concrete box that stops traffic, but of course it’s so much more than that, as Jane Jacobs herself would attest.

June 14, 2015

Street Symphony by Rachel Wyatt

“‘This is what I want,’ he heard a woman saying. ‘That’s what I want.’ She seemed to be addressing the world at large. When he came closer, he saw she was pointing at a forty-inch flat screen TV in the store window.” –from “Caffe Italia”

“‘This is what I want,’ he heard a woman saying. ‘That’s what I want.’ She seemed to be addressing the world at large. When he came closer, he saw she was pointing at a forty-inch flat screen TV in the store window.” –from “Caffe Italia”

Nothing is ever quite what it seems in Rachel Wyatt’s new short story collection, Street Symphony. Everybody has a secret life, or else a secret grudge. Bodies fall from rooftops on quiet streets, mothers monitor their adult sons’ email, the woman furtively taking notes at the bar has her own agenda, and then there’s the character walking around town holding a sign asking, “Are you content to be nothing?” Disturbing the quiet of leafy streets has been what Wyatt’s been up to for the last forty years, with novels like The Rosedale Hoax (1977), a satiric comedy set in Toronto’s tony neighbourhood. In Street Symphony, Wyatt’s voice and point of view are just as strong and distinctive.

What that point of view is exactly depends on where one is standing. Or sitting, in the case of the story, “Falling Woman,” in which a character happens to choose a different seat in her living room in which to drink her coffee and read her paper one morning, and thereby observes somebody falling out of the sky. Her usual chair, and she would have missed it. And usual chairs populate the “Caffe Italia” story, which is a microcosm of the collections, in which early morning regulars in a coffee shop tell themselves stories of other people’s lives—and of their own. These are stories about the infinite number of ways that we brush up against each other, but how much we get wrong in the process of knowing. How we are each of us alone, connected only to each other, to paraphrase a line from Marina Endicott’s Close to Hugh, which makes an interesting complementary read to this one. How Wyatt’s characters see the world and each other depends on which direction each one is facing, and perhaps whether they’ve got their curtains closed or open, and all manner of other details.

Wyatt is a tricky writer, her narratives rushing forward and trusting their reader to keep up and to follow the twists and turns of plot and dialogue. Characters aren’t introduced but just appear in full force and action, and we’re to put the pieces together to find out who they are just as those characters discern the lives of the people they encounter in their own circles. Some of these stories will invite a reread upon finishing, and even then, not all the details will be clear. Mysteries remain, secrets kept, puzzles unresolved. Wyatt uses elements of intrigue as she did in her 2012 novel Suspicion, not always to full effect here, but still they keep the stories interesting. There are 17 in this collection and they don’t blend together, but have a cumulative force, building like into symphony of the title, layers of city life. And a few satirical suburban cul-de-sac stories reminded me of Zsuzsi Gartner’s Better Living Through Plastic Explosives, so we’re not just talking about the downtown core.

June 12, 2015

Better late than never

I don’t know that much about irises, except that we’ve had them blooming in our front garden in previous years. The year Iris was born, they were out on her due date, though by her birth date (two weeks later) they’d already been and gone. But this year, while there have been irises throughout the neighbourhood for weeks now (just around the time the lilacs peaked), our garden hasn’t yielded a single one. Where had the irises gone, I wondered? But then this morning on our walk to school we realized that the strange spiky stalks in the middle of the garden had been irises all along—just in hiding. It turns out that we really don’t know much about irises at all, until they spring into bloom. Which is happening a few weeks late this year because our garden is north-facing and mostly always in the shade, I think. But happening nonetheless, because by school pick-up, the flowers had opened up. Better late than never.

I don’t know that much about irises, except that we’ve had them blooming in our front garden in previous years. The year Iris was born, they were out on her due date, though by her birth date (two weeks later) they’d already been and gone. But this year, while there have been irises throughout the neighbourhood for weeks now (just around the time the lilacs peaked), our garden hasn’t yielded a single one. Where had the irises gone, I wondered? But then this morning on our walk to school we realized that the strange spiky stalks in the middle of the garden had been irises all along—just in hiding. It turns out that we really don’t know much about irises at all, until they spring into bloom. Which is happening a few weeks late this year because our garden is north-facing and mostly always in the shade, I think. But happening nonetheless, because by school pick-up, the flowers had opened up. Better late than never.

June 11, 2015

Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild by Mem Fox and Marla Frazee

Okay, can we just stop for a moment while I tell you how I worship at the feet of Marla Frazee‘s entire career? The woman behind some of the great picture books ever—Everywhere Babies, The Seven Silly Eaters, and All the World. Her own books too—Roller Coaster and The Farmer and the Clown. Her images are so vibrant, complex, textured, diverse, her world so detailed, her babies so perfect, and her toddlers so perfect…ly devious. I love her. I love her. I do.

I read somewhere once (or else I dreamed it?) that Marla Frazee was not the original illustrator for Harriet You’ll Drive Me Wild, and that there exists somewhere a completely different edition of this book. I am unclear as to the veracity of this rumour not just because I can’t find a single shred of evidence supporting it, but more because it seems unfathomable. (Update: but it’s true! The book was first published in 1986 as Just Like That, illustrated by Kilmeny Niland.)

My neighbours gave me their old copy of this book (the 2003 edition) when my Harriet was three weeks old. I remember sitting in the chair by the window, the scene of innumerable struggles to get the baby to latch, and how here was a book very different than the others we’d been reading in that storm. Different from the new parenting books I’d already filled with my manic marginalia, and different from the baby board books with their saccharine endings (which were somehow always about going to sleep. I wondered, when was that part going to happen?). Here was a book that gave me a glimpse of the future, of a time in which my new baby might not be small enough to tuck in neatly across my chest as we napped on the couch—shocking. A glimpse of a child-to-be, full of energy, beans and mischief.

Where Fox’s Harriet was once my future, six years later, she’s now the past. The character is about three, I think, not intending any trouble (which, according to the text, always happens “just like that”). Frazee’s images show another reality, however, of squirms, experiments, curiosity, contortions and shenanigans—but still, she can’t help herself. “Harriet Harris was a pesky child. She didn’t mean to be. She just was.”

There are so many things I love about this book. First, that it’s Mem Fox, whose work has been so essential to my happiness as a parent. (Read Where is the Green Sheep and not be happy. I dare you.) Second, it’s a literary Harriet, and we love these. Third, that it depicts a very realistic mother, a bit frumpy and struggling to get her own things done while her daughter thwarts her at every turn. (I imagine that between the pages, she is ignoring her daughter and scrolling through Twitter.) And shows that a mother can get angry (for good reason) but that this is okay. Things—people and pillows—can explode, but that doesn’t mean that it can’t be made all right again.

But the foremost reason I love this book is because of the text, and how the lines build on one another along with the mother’s frustration. She begins with her patience tested, saying (because she doesn’t like to yell), “Harriet my darling child. Harriet, you’ll drive me wild.” And that added on to that by the end is, “Harriet, sweetheart, what are we to do? Harriet Harris, I’m talking to you.” Delivered in harassed mother voice. The alliteration of the name is delicious to say, along with the rhyme. I love the consternation.

Reading the part of a mother in a book is rarely quite so nuanced and interesting.

June 10, 2015

Iridescent comes from Iris

From Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, by Mary Norris:

From Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, by Mary Norris:

“Etymology” is from the Greek and means the study (logia) of the “literal meaning of a word according to its origin” (etymon). (Not to be confused with “entomology,” the study of insects [entomon].) It can be a huge help n spelling. For instance, people sometimes misspell “iridescent.” It’s a trick that often appears on copy-editing tests. Webster’s Collegiate supplies this enthusiastic definition for “iridescence”: “a lustrous rainbowlike play of colour caused by the differential refraction of light waves (as from an oil slick, soap bubble, or fish scales) that tends to change as the angle of your view changes.” Rather than just try to memorize the spelling, if you look at the etymology—study the entrails of the word—you find that “iris, irid” is a combining form that comes from the Greek Iris, the goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the gods. Wow! Like Webster, I could go off the deep end in finding significance in this: it seems like magic—a word that appeared in Homer’s Iliad and that we associate with Noah’s ark (the rainbow), and with optimism and promise, connects with puddles in Cleveland that I marveled at as a girl (there was a lot of grease in the puddles in Cleveland) and an indelible image from the opening pages of The Catcher in the Rye, in which Salinger has Holden remark on the “gasoline rainbow.” Anyway, once you know that “iridescent” comes from Iris, you’ll never spell it wrong.

(Am reading this book on the recommendation of Ann Patchett, and enjoying it very much. Even the parts without irises.)

June 10, 2015

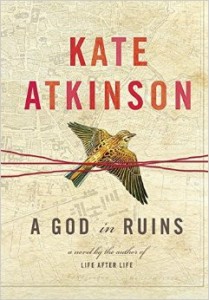

My Best Books of the Year (so far!)

Nearly midway through the year, I can say that 2015 has yielded some wonderful books. And while the difficult thing about having a mind is that details fall out of it as time passes, a blog can counter that. So let’s remind us both of the best things I’ve read this year (so far!) and perhaps some of the titles can spur on your own summer reading list.

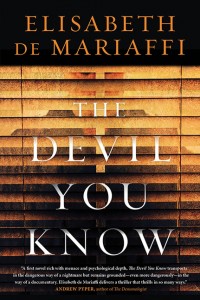

The Devil You Know, by Elisabeth de Mariaffi

The Big Swim, by Carrie Saxifrage

Born to Walk, by Dan Rubinstein

Welcome to the Circus, by Rhonda Douglas

June 7, 2015

The Green Road by Anne Enright

I’m not quite sure what to do with The Green Road, by Anne Enright. Enright, recently appointed Ireland’s first Fiction Laureate, a literary force whose new books are events, winner of the Man Booker Prize for 2007’s The Gathering. I read The Gathering after the award, I think, and I remember finding it very difficult, and no longer remember anything about it. Her following novel, The Forgotten Waltz, was more my speed, more of a straightforward narrative, though critics found it underwhelming. I loved her memoir, Making Babies, which I’ve read at least twice, a book that displays her wry, slightly-off perspective, and her mastery of language. Oh, how Enright can line up words in a sentence, evoke a simile: the effect of “He did have sex with a guy on Saturday night but coming made him feel like he was reaching for something that melted in his hands.” (from The Green Road). Last winter I read her second novel, What Are You Like? from 2000, and found myself spellbound but frustrated by the fragmentation. Sometimes I feel as though fragments emerge from an author who couldn’t quite be bothered to write a “real” book, but then the pieces all came together at the end and I was dazzled all the same.

I’m not quite sure what to do with The Green Road, by Anne Enright. Enright, recently appointed Ireland’s first Fiction Laureate, a literary force whose new books are events, winner of the Man Booker Prize for 2007’s The Gathering. I read The Gathering after the award, I think, and I remember finding it very difficult, and no longer remember anything about it. Her following novel, The Forgotten Waltz, was more my speed, more of a straightforward narrative, though critics found it underwhelming. I loved her memoir, Making Babies, which I’ve read at least twice, a book that displays her wry, slightly-off perspective, and her mastery of language. Oh, how Enright can line up words in a sentence, evoke a simile: the effect of “He did have sex with a guy on Saturday night but coming made him feel like he was reaching for something that melted in his hands.” (from The Green Road). Last winter I read her second novel, What Are You Like? from 2000, and found myself spellbound but frustrated by the fragmentation. Sometimes I feel as though fragments emerge from an author who couldn’t quite be bothered to write a “real” book, but then the pieces all came together at the end and I was dazzled all the same.

I wasn’t so dazzled by The Green Road, which is also a novel in pieces, or at least I wasn’t dazzled by how the pieces finally came together because they didn’t really. But then the pieces themselves were really stunning, and it’s remarkable too how Enright portrays 25 years of a family’s history through a few chosen episodes most of which don’t even show characters interacting with other family members. We begin with Hanna, the youngest daughter in 1980, witnessing her formidable mother’s histrionics at her eldest brother’s decision to join the priesthood. Next it’s 1991 in New York City, and the brother has foregone religion for an vibrant life in the city’s gay scene against the backdrop of AIDS. 1997 and sister Constance is awaiting confirmation of whether or not the lump in her breast is cancerous, the entire section enacted in the events of a single morning. Then 2002 and brother Emmet is doing international development work in Mali, negotiating his own perilous domestic arrangement with a fellow aid worker. And finally, their mother, Rosaleen, sitting down to her Christmas Cards in 2005 and contemplating her children so far dispersed emotionally and by geography. She’s selling the house, she decides, a surprising decree that brings everyone home for the first time in years.

Each of these pieces stand alone as a masterful short story. Stylistically innovative too—in particular the first-person plural narration of Dan’s section. They are challenging, stories that begin in the middle of the action, or afterwards, taking a long time to circle back around to it, demanding much of their reader’s attention. If you try to skim prose like this, you’re going to get lost. They also serve well as a shorthand of the family’s place in time through small details, even if the character’s family life is at the far periphery of their experience. And that the family life is at the far periphery of experience is kind of the point of the entire book, their demanding mother both the cause of and reacting to the fact that her offspring are so far-flung. So what happens when the fractured family all return again under one roof?

There is drinking, of course. Enright has done a fantastic job rendering the postpartum experiences of struggling actress Hanna whose been hiding booze in her juice, and is dangerously unstable. Everyone gets sloshed, except put-upon Constance who magics up Christmas dinner (but forgets to buy the coffee) and then after the inevitable explosion when their mother takes off, no one is sober enough to go driving and look for her. And here the novel takes a dramatic turn, a bit Hagar Shipley/Our Woman from Anakana Schofield’s Malarky, the embittered and deranged mother figure getting lost in the landscape, falling off the edge of things. (The kind of woman who thunders around screaming, “Don’t mind me!” at the night sky.)

It is this difficult woman who is the book’s compelling centre, but never quite comes into focus. This is also partly the point—the characters contemplate the impossibility of really describing one’s mother. She is just your mother—a primal knowledge, but also one beyond understanding. The hole at the centre of the novel gets at this contradiction, but it’s also a weakness of the book, I think. And while it’s emblematic that the pieces of the narrative fail to culminate into anything approaching resolution, the reader is still looking for more of a pay-off.

Though it’s there if you look for it. In Enright’s exquisite prose, the illumination of perfect moments throughout the text (even if they are more like beads on a string than links on a chain), in what Lisa Moore describes as Enright’s “distinctive voice. Captivating, wry, tart, wickedly funny – ineffable, ineluctable.” So in the end, I do know what to do with Anne Enright, which is just to read her, read everything, and then go back and read The Gathering again.

June 5, 2015

Happy Birthday, Iris

“You are mighty, you are small. You are ours after all.”

“You are mighty, you are small. You are ours after all.”

Two years ago today, the world delivered us the funniest little person. Two weeks late, covered in peeling skin like a reptile, and with two teeth coming in already. Received into a family that was ready for her, waiting for her, and was made complete once she was finally here. “I hope you don’t mind that I put down in words, how wonderful life is while you’re in the world,” is the song I sang to her first when she was four days old (while I was eating sashimi in bed, Stuart was hanging laundry, and Harriet was doing her Thomas the Tank Engine sticker book), and I’ve sang it every day ever since.

She is ferocious, and very noisy, and perhaps the mostly likely person in the world not to be lost in Harriet’s shadow. She pinches, bites and spits, which is charming. When she behaves badly, we’ve been telling her to go away, but now she’s started screaming at US to go away (or at Harriet, after she has pinched her and drawn blood, which doesn’t really help matters). She will not sit down, ever. We are used to her standing on table tops and benches, but it makes other people nervous. She is attracted to the margins of things—she walks on walls, likes gutters and ditches. She walks on the grass beside the sidewalks, and picks the dandelions, and yesterday she discovered what happens when the dandelions seeds all blow apart—like magic—and the look on her face was pure ecstasy.

She is a funny one. Last week during dinner, it occurred to me that she looks like Anne Enright. “Iris is cuter than Anne Enright,” someone emailed me after, but I think that Anne Enright is adorable. They both look like a mischievous elf, or else a grumpy one. Iris has no idea that she is only two. She conducts long and elaborate conversations in gobbleygook while waving her hands emphatically. She can laugh and laugh at nothing, just eager to be in on the joke. (“Knock knock,” she says. “Who’s there?” we ask her. “Oofoo,” she says. “Oofoo Who?””Apple!”) She calls dogs “oeufs” and whenever she passes one, she says, “Allo oeuf.” She continues to have a French Canadian accent, and calls her sister ‘Arriette. She loves to sing Baa Baa Black Sheep, the Annie soundtrack, and Let It Go. She literally learned to sing before she could talk. She talks all the time now. She dances all the time too. She’s going to playschool in September and I think she’s going to love it.

She is a funny one. Last week during dinner, it occurred to me that she looks like Anne Enright. “Iris is cuter than Anne Enright,” someone emailed me after, but I think that Anne Enright is adorable. They both look like a mischievous elf, or else a grumpy one. Iris has no idea that she is only two. She conducts long and elaborate conversations in gobbleygook while waving her hands emphatically. She can laugh and laugh at nothing, just eager to be in on the joke. (“Knock knock,” she says. “Who’s there?” we ask her. “Oofoo,” she says. “Oofoo Who?””Apple!”) She calls dogs “oeufs” and whenever she passes one, she says, “Allo oeuf.” She continues to have a French Canadian accent, and calls her sister ‘Arriette. She loves to sing Baa Baa Black Sheep, the Annie soundtrack, and Let It Go. She literally learned to sing before she could talk. She talks all the time now. She dances all the time too. She’s going to playschool in September and I think she’s going to love it.

She also loves her birthday presents, being as passionate about tea, cakes and bunting as everyone else in our family. I love that her limited vocabulary contains the term “book barge.” She does her best to keep up with the big kids, and will not be pandered to—she eats EVERYTHING with a fork, because babies are often denied cutlery, to the point where she eats sandwiches and goldfish crackers with a fork. Do not put a lid on her glass of water either, though that is less because she doesn’t want to be pandered to than she wants to drop her bread in it and then drink the water with a spoon. And while she is the endless tormentor of her poor sister, she also adores her. Wants to go and find her first thing every morning (and not necessarily just to bite her). She has her own flower, and she knows it, though she is also quite insistent that pansies are irises too. She gives the best hugs, is quite the snuggler, adores her daddy, walks everywhere (but more often runs), likes ketchup, is a juice fiend, and is usually somewhere screaming for cake.

She also loves her birthday presents, being as passionate about tea, cakes and bunting as everyone else in our family. I love that her limited vocabulary contains the term “book barge.” She does her best to keep up with the big kids, and will not be pandered to—she eats EVERYTHING with a fork, because babies are often denied cutlery, to the point where she eats sandwiches and goldfish crackers with a fork. Do not put a lid on her glass of water either, though that is less because she doesn’t want to be pandered to than she wants to drop her bread in it and then drink the water with a spoon. And while she is the endless tormentor of her poor sister, she also adores her. Wants to go and find her first thing every morning (and not necessarily just to bite her). She has her own flower, and she knows it, though she is also quite insistent that pansies are irises too. She gives the best hugs, is quite the snuggler, adores her daddy, walks everywhere (but more often runs), likes ketchup, is a juice fiend, and is usually somewhere screaming for cake.

Two is a trial. I remember this. When Harriet was two, she had to be carried out of everywhere screaming, “More more more!” Iris is similarly passionate, but on a different keel. When she gets angry, she likes to hurl things to the floor. But two is also amazing—the onslaught of words that arrive, so that there are stories to tell, secrets share, and more jokes than just oofoo. It’s incredible to have a sense of how much better we’re going to get to know her over the next year—she’s going to have her own idea for a Halloween costume, I mean, and when she turns three, she’ll choose her birthday theme. (When Harriet was three, it was dinosaurs.) She’s going to be a person with tastes, beyond just the “cake cake cake” that’s her speed now. I am excited to discover them. I am also excited to trim her fingernails more often so that my skin doesn’t get so maimed in the midst of her rages.

While life certainly is not ALWAYS wonderful while Iris is in the world (she is so exasperating), it is completely wonderful on a different level. As in, you are terrible, but you are here, and we love you. Sometimes it is really as simple as that.

June 4, 2015

Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney

The reason why Barbara Cooney’s Miss Rumphius was one of my favourite books as a child was because of its expansiveness. In terms of geography—we see images from her travels all around the globe, and on a micro level as she winds her way along paths and roads in her New England town so that we see the school, the church, the houses of her neighbours. Images on the horizon and ships on the sea (and the highways that stretch off the page in two directions) suggest interconnectivity, the wider world, a sense of wholeness. And so too does Cooney portray a single life with such largesse, beginning with young Alice as a child painting in the skies in her father’s pictures, and finishing with Alice as an old old lady (as narrated by her grand-neice), as well as everything in between.

As an adult reader, I still admire the hugeness of Cooney’s canvas, but I am most fond of the book for its feminist overtones. Because here we have young Alice who knows exactly what she’s going to do with her life—she’s going to travel to far away places, and then come home to live beside the sea. (There is a third thing she must do, according to her grandfather—she must make the world a more beautiful place.) Here then is the story of a woman’s life that neither begins nor ends with a wedding—in fact, there isn’t a wedding at all. I suppose we’d call her a spinster, but she’s a woman who’s always been called by her own name: Miss Rumphius, The Lupine Lady, Great Aunt Alice. (Admittedly, she is also referred to as That Crazy Old Lady, but she doesn’t appear particularly bothered.)

Here is the story of a woman who goes through the world sowing her seeds, leaving her mark, living precisely as she said she would. She doesn’t stop travelling the world and courting adventure until she hurts her back getting off a camel, and only then does she come home to her place beside the sea. She doesn’t conform to society’s expectations of femininity, but lives by her own rules. (A similar plot is more explicit in Cooney’s picture book, Hattie and the Waves. Cooney has described both books, as well as Island Boy, as as close as she’d ever come to writing an autobiography. Surprisingly though, Cooney was married—twice!)

As a feminist, it’s possible that this was my foundational text.

There are a few troubling points about the book involving cultural stereotypes. See Debbie Reese’s post about what’s wrong with the reference to the cigar store Indian, and I’m also uncomfortable with the colonial feel of Miss Rumphius’s travels throughout the world. Both issues can be the start of worthwhile discussions with young readers though, two of many spurned on by the richness of Cooney’s words and images. These points should not be ignored, but are no good reason to throw the book out altogether.

I love so many things about this book. That it’s an entire lifetime distilled into a few words and pictures, that she works as a librarian, the greenhouse, the cat, that she gets sick and then gets better again, that the story affords that life itself brings bumps along the way. It’s the kind of books whose illustrations I’d get lost in, tracing my fingers down the roads, examining the details of the paintings on the wall. And the light of the sunset on the very last page, the children gathering lupines that Miss Rumphius planted. I love the cyclical nature of the story, it’s open end, which is a challenge to the reader herself.

Throughout summer, I will be devoting Picture Book Fridays to classic picture books I love.

June 2, 2015

Specimen by Irina Kovalyova

It is true that I’ve quite possibly been inspired by the title and exquisite cover of Irina Kovalyova’s short story collection, Specimen (a cover that is so exquisite. When I went on the subway yesterday, everybody was staring at me and then I realized that everybody was staring at my book), but the stories in the collection do remind me of nineteenth-century taxonomy specimens. Something that is pinned to a board in flagrant beauty, luminous, remarkable, but not quite living. Devoid of life for the purposes of examination, but how the examiner is fascinated anyway. The variety of specimens, their perfect detail, lines and edges—I can’t stop thinking about these stories. They’re good enough that I can start this review off with my criticisms, and then move along to why the collection is absolutely worth reading all the same.

It is true that I’ve quite possibly been inspired by the title and exquisite cover of Irina Kovalyova’s short story collection, Specimen (a cover that is so exquisite. When I went on the subway yesterday, everybody was staring at me and then I realized that everybody was staring at my book), but the stories in the collection do remind me of nineteenth-century taxonomy specimens. Something that is pinned to a board in flagrant beauty, luminous, remarkable, but not quite living. Devoid of life for the purposes of examination, but how the examiner is fascinated anyway. The variety of specimens, their perfect detail, lines and edges—I can’t stop thinking about these stories. They’re good enough that I can start this review off with my criticisms, and then move along to why the collection is absolutely worth reading all the same.

Specimen is the first book by Irina Kovalyova, multi-talented holder of a doctorate in microbiology, an MFA in creative writing from UBC, who is a microbiology instructor at Simon Fraser University, and a onetime NASA intern. And it’s the singularity of her point of view (the lines, edges and details, the wideness and wildness of her premises) that exalts these stories, though a few of them aren’t completely realized. Some reveal flat characterization, unsatisfying endings, seem to be experiments that were not entirely pulled off. Not atypical first book fare. And yet and yet and yet.

Reading these stories, I kept thinking about Michael Chabon’s essay, “Trickster in a Suit of Lights: Thoughts on the Modern Short Story,” which hearkens back to the days (pre-1950s) when the short story fell into the realm of entertainment: “the ghost story; the horror story the detective story; the story of suspense; terror; fantasy; science fiction, or the macabre; the sea, adventure, spy, war, or historical story; the romance story.” These days, he writes, it is novelists who write (and find success) in that wild space between genre and literary and find much success there, while the short story pines away often unread and boring. And so into the wild spaces, Chabon writes, is where the short story must go, and it’s into these very same spaces where Kovalyova takes her readers.

Which makes for a fascinating ride. “Mamochka” is the story of the Chief Archivist at the Institute of Physics in Minsk who is pining for her grandchild far away in Vancouver, and whose own derangement is manifesting in curious ways. “The Ecstasy of Edgar Alabaster” is a story not quite what it seems, a nineteenth-century record of a patient under hypnosis who confesses to sexual perversions and an incestuous relationship with his sister (and then the whole story collapses into a marvellous hall of mirrors). In “The Side Effects,” a patient’s Botox injections smooth out her psyche as well as her skin, but life without its wrinkles turns out to be lacking in magic.

“Gdansk” is a story of numbered items, a narrative suggesting some pattern in a chaotic universe, a post-Cold-War story of youth, adventure and “anticipating the world.” In “Specimen,” a young woman discovers she was conceived via a sperm donor, and must come to a new understanding about the relationship between genetics and fatherhood (and is saved from disaster by her friend who recognizes that her frontal lobe is not yet developed enough for her to make important decisions). That story takes a dark turn at one point, which steers us directly into “Peptide p,” a story of experiments on two children who’d survived an epidemic (tainted hotdogs) that felled their classmates, a story whose creepiness is subtle and slow, and becomes terrifying by the end.

In “Gonos,” a biology professor considers the troubling product of his own genes as he teaches a lecture on the nature(s) of sex and gender, considering the “correctness” or “incorrectness” of life and coming to a beautiful, hopeful conclusion in the end. And in “The Big One,” the ending is ambiguous but maybe hopeful (?), as a woman and her child are trapped in an underground parking garage after an earthquake, the narrative dividing into two—their dialogue and the woman’s interior monologue. Also a gorgeous ending: “Without imagination, life makes no sense.” A notion that takes us so many different meanings in relation to the stories in this book. The key that holds it all together.

The final story is the novella, “The Blood Keeper,” which I was instantly drawn into. But how could I not be? The first line is, “My father, Viktor A. Mishkin, was the keeper of Lenin’s mummy.” Vera is a biologist studying orchids when her father is sent on a mission to North Korea in 1996 to preserve the body of the recently-deceased Kim Il Sung. She receives a curious letter from him imploring her to follow him to Pyongyang as part of a student exchange where she becomes embroiled in several plots involving love and intrigue. A fantastic read, rich with details and suspense, “The Blood Keeper” reveals Kovalyova as a writer firmly in command of her materials.

So in the end, yes, even with its imperfections (and what specimen does not possess some of these, I suppose) Specimen is a book wholly worthy of its cover. A collection of beauty, light, colour, curios, permitting readers access into worlds that are usually unexamined, those wild spaces in between.