November 14, 2014

Disposable women, forever and always

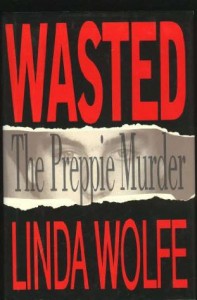

We always had true crime books lying around the house when I was little, and since I read everything, these books were no exception, and I do wonder how the 10 year old’s psyche is affected by rigorous rereadings of Blind Faith by Joe McGinniss. I have a better sense of the impact of Wasted: The Preppie Murder by Linda Wolfe, the story of the murder of 18 year old Jennifer Levin in New York City by a man who strangled her in a park and pleaded guilty to manslaughter—the death was a result of “rough sex”, he said. (When police found him the next day, he was covered with scratches. He claimed he’d been attacked by his cat.) Which is that from very early on, I learned that there were some men for whom women were completely disposable, and that our justice system is stacked against victims of sexual violence in a way that is absolutely heinous.

I’ve been thinking about Jennifer Levin’s death since yesterday, when the verdict was delivered in another case involving the death of a teenage girl. We all know her name, but no one is permitted to print it, which means just this: you can indeed be prosecuted for using a rape victim’s name, but you can actually photograph the victim being raped and then share the image on social media—destroying the self-esteem and reputation of a teenage girl, who goes on to commit suicide—and receive a punishment that involves writing a letter of apology and attending a course on sexual harassment. “He must learn how to properly treat females,” is part of the judge’s verdict, as though this is something that must be taught, as though knowing “how to treat females” (who are indeed people) isn’t sort of one of the barest prerequisites for being a human being.

I’ve been thinking about Jennifer Levin’s death since yesterday, when the verdict was delivered in another case involving the death of a teenage girl. We all know her name, but no one is permitted to print it, which means just this: you can indeed be prosecuted for using a rape victim’s name, but you can actually photograph the victim being raped and then share the image on social media—destroying the self-esteem and reputation of a teenage girl, who goes on to commit suicide—and receive a punishment that involves writing a letter of apology and attending a course on sexual harassment. “He must learn how to properly treat females,” is part of the judge’s verdict, as though this is something that must be taught, as though knowing “how to treat females” (who are indeed people) isn’t sort of one of the barest prerequisites for being a human being.

“Why didn’t he help her?” I wonder. The boy with the camera, I mean, or any of his friends, or the police who shrugged when the victim came to them with the actual photo of her rape being committed, and who found no way to prosecute any of the perpetrators (for distributing child pornography—the charge that has a man punished by letter of apology) until after her death by suicide. Why did nobody help?

Let alone, why are there people actually defending the perpetrators? The same kind of people who are bothered by rape charges ruining the lives of nice young men, or promising footballers? What kind of inside out world do we live in? The kind of world in which the parents of a young man who talks about having his colleague raped as a kind of punishment actually speak out in defence of their son? If that were my son, I’d draw the curtains and not go out again for a very long time. Have these people no shame? “We ask you to give him the chance to learn,” the parents say, to which I respond with a vehement, NO. One does not have to learn about how it’s wrong to talk about raping one’s colleagues (or anybody). If you don’t know this already, you never ever will.

When Toronto’s terrible mayor and a godforsaken excuse for a human being was diagnosed with cancer last fall, I fumed as public figures postured about prayers being with him etc. etc. This is another man who has not yet learned that it’s wrong to talk about raping one’s colleagues. It was all I could think of, as his ass fat tumour came down, that a public figure gets to say the things he said (let alone do the things he did) and then get up there with a whole lot of actually honourable citizens and campaign beside them for the job of mayor. “But no!” somebody protests, “do not make disparaging remarks about a man with cancer.” Because we’re willing to draw a line there—we are moral after all—but it’s women who are disposable, women who are nothing more than something for you to stick your dick in, or make jokes about sticking your dick in. A dick receptacle. And if that’s not enough, you can choke them too, “rough sex,” says another public figure, not even sheepishly. And now I’m thinking about Jennifer Levin again, a moment in time, 1980s’s excesses, but it’s forever and always. This is the world in which we live.

You can call it rape culture. You can call it the most horrendous, pervasive male entitlement too. But not all men, another voice pipes up, but oh, there are ever so many. Some of whom are even seemingly feminist allies, examining complicity as they forget about the women whose bodies they themselves have groped, and carrying banners at feminist rallies, even. These men are fathers, husbands, brothers and sons—to frame things in those terms. And I don’t know what to do.

In The New Quarterly 131, Karen Connelly’s essay, “#ItEndsHere,” parallels Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan’s seeming unconcern with the disappearance of 300 school girls with Canada’s own lack of response to the more than a thousand missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women in this country. (The most recent in the news is the young girl in Winnipeg, Rinelle Harper, who was assaulted twice and thrown in the same river where 15 year old Tina Fontaine’s body was discovered months ago. Mercifully, Rinelle Harper survived. She is recovering in hospital.) Connelly reminds us of the rumours surrounding the farm where the remains of so many women were eventually discovered—those rumours would not be investigated for years, during which time so many women died. Disposable women. Ineffectual authorities. There’s a pattern here. It’s like stringing beads.

In The New Quarterly 131, Karen Connelly’s essay, “#ItEndsHere,” parallels Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan’s seeming unconcern with the disappearance of 300 school girls with Canada’s own lack of response to the more than a thousand missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women in this country. (The most recent in the news is the young girl in Winnipeg, Rinelle Harper, who was assaulted twice and thrown in the same river where 15 year old Tina Fontaine’s body was discovered months ago. Mercifully, Rinelle Harper survived. She is recovering in hospital.) Connelly reminds us of the rumours surrounding the farm where the remains of so many women were eventually discovered—those rumours would not be investigated for years, during which time so many women died. Disposable women. Ineffectual authorities. There’s a pattern here. It’s like stringing beads.

Connelly writes, “When there were enough missing women—68 to be exact…—the police finally began to look for them. The investigation into the missing women of the downtown east side began in 1998. [Redacted] continued committing murders until his arrest on February 22, 2002.” And from her poem, “Enough,” from her recent collection, Come Cold River:

Unfold the maps on the table.

Let me show you hell.

As described in The Globe and Mail.

Oddly, it includes English Bay,

blue salt water, sand, crows,

owls in the cedars.

The road out?

Oh, that remains

under construction.

November 13, 2014

Vacant Possession by Hilary Mantel

I so much loved spending a weekend reading Hilary Mantel two weeks ago that I decided to do it again last weekend with Vacant Possession. It’s the sequel to the brilliantly funny Every Day is Mother’s Day, which was Mantel’s first published novel and one of the first Hilary Mantel books I ever read (around the time Beyond Black came out). While I love Mantel’s writing and she’s always amazing, her enormous range (domestic fiction, the fantastic, historical epics) means that not everything she writes appeals to me. I struggled through Wolf Hall, and that’s it for me for the Cromwell trilogy, but the upside to its Booker success is that Vacant Possession—the sequel to Every Day is Mother’s Day—is in print now, whereas it wasn’t in 2006.

I so much loved spending a weekend reading Hilary Mantel two weeks ago that I decided to do it again last weekend with Vacant Possession. It’s the sequel to the brilliantly funny Every Day is Mother’s Day, which was Mantel’s first published novel and one of the first Hilary Mantel books I ever read (around the time Beyond Black came out). While I love Mantel’s writing and she’s always amazing, her enormous range (domestic fiction, the fantastic, historical epics) means that not everything she writes appeals to me. I struggled through Wolf Hall, and that’s it for me for the Cromwell trilogy, but the upside to its Booker success is that Vacant Possession—the sequel to Every Day is Mother’s Day—is in print now, whereas it wasn’t in 2006.

And it’s so wonderful. It takes place in Thatcher’s Britain, 1984. The nefarious Muriel Axon has been released from her institution ten years after the mysterious death of her horrible mother, and she’s determined to seek revenge upon those she feels wronged her all those years ago—namely her former social worker, Isobel Field, and Isobel’s old lover, Colin Sidney, who has since reconciled with his wife and moved into Muriel’s old home. Her move from institutional care to “care in the community” is part of a downloading of government services typical of the time (and our time too), and Mantel paints its consequences in a way that is as hilarious as it is chilling—and it’s only hilarious until you realize how close to life this satire is drawn. Such terrible stupid people, and Mantel is unafraid to paint them as such, which is funny until you realize you’re probably laughing at yourself.

But it is funny, and fiercely political, fearless, and smart and wonderfully written. Really, a single book can be this good, and hilarious escape and a punch in the gut all at once. Proving we really do need to set our standards for fiction higher, I think, so why not start here. Right now. Go.

November 12, 2014

New Kids’ Books We’ve Been Enjoying Lately

With Harriet in school all day and Iris’s chief occupation being hurling books to the floor (save for Hand Hand Fingers Thumb, which she’s really into lately, and hurls at me when she’s demanding it read), I’m not quite as immersed in the land of picture books as I once was. But still, I’ve been keeping track of our stand-outs and making a list to share with you—perhaps you’ll find some ideas for Christmas gifts? Also recommended are the most recent winners of the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards.

I’ve written already about Super Red Riding Hood by Claudia Davila, and since given about four copies away as gifts. “It’s about a little girl called Ruby who likes to fancy herself a defender of justice and imagine stories in which she gets to prove her super-hero mettle. While a trip through the woods to collect raspberries isn’t quite the mission she’s been fantasizing about, Ruby makes the most of it, rescuing small creatures and being brave in the face of weird woodland sounds. And so she’s totally ready when she stumbles into a situation requiring actual super-heroics, and has to stare down a ferocious wolf.”

I’ve written already about Super Red Riding Hood by Claudia Davila, and since given about four copies away as gifts. “It’s about a little girl called Ruby who likes to fancy herself a defender of justice and imagine stories in which she gets to prove her super-hero mettle. While a trip through the woods to collect raspberries isn’t quite the mission she’s been fantasizing about, Ruby makes the most of it, rescuing small creatures and being brave in the face of weird woodland sounds. And so she’s totally ready when she stumbles into a situation requiring actual super-heroics, and has to stare down a ferocious wolf.”

We also love Dolphin SOS by Roy Miki and Slavia Miki, with illustrations by our beloved Julie Flett. It’s from the perspective of a young girl in a community on the coast of Newfoundland rattled by three dolphins trapped in ice in their bay. The girl’s older brothers play a part in the rescue, which ends in triumph. It’s a terrific story, based on true events, and Julie Flett’s illustrations are oh, so beautiful. Is it weird to be crazy about a kids’ book because you covet the wallpaper patterns in the character’s house?

We also love Dolphin SOS by Roy Miki and Slavia Miki, with illustrations by our beloved Julie Flett. It’s from the perspective of a young girl in a community on the coast of Newfoundland rattled by three dolphins trapped in ice in their bay. The girl’s older brothers play a part in the rescue, which ends in triumph. It’s a terrific story, based on true events, and Julie Flett’s illustrations are oh, so beautiful. Is it weird to be crazy about a kids’ book because you covet the wallpaper patterns in the character’s house?

When I heard tell of a collaboration between Kyo MacLear and Julie Morstad, I almost had a heart attack. I love Kyo MacLear’s picture books, which are strange, absorbing, curious and delightful, and then there’s Julie Morstad, whose illustrations are so beloved I buy her prints and hang them on my wall. Julia, Child did not disappoint, this story loosely based on Julia Child’s friendship with collaborator Simca Beck. Two girls, inexplicably wearing roller skates, delight in fine cooking, and decide to cater a party to remind grown-ups about the good things in life. Plans go awry a bit, but it all gets sorted out, and the guests remember it’s best to remain a child at heart. The book is delicious and will make you hungry.

When I heard tell of a collaboration between Kyo MacLear and Julie Morstad, I almost had a heart attack. I love Kyo MacLear’s picture books, which are strange, absorbing, curious and delightful, and then there’s Julie Morstad, whose illustrations are so beloved I buy her prints and hang them on my wall. Julia, Child did not disappoint, this story loosely based on Julia Child’s friendship with collaborator Simca Beck. Two girls, inexplicably wearing roller skates, delight in fine cooking, and decide to cater a party to remind grown-ups about the good things in life. Plans go awry a bit, but it all gets sorted out, and the guests remember it’s best to remain a child at heart. The book is delicious and will make you hungry.

We like Fire Pie Trout by Melanie Mosher and Renne Benoit, published by Aboriginal Publishers, Fifth House. I like it because I have memories of going “fishing” with my grandfather when I was little, the fishing rods he made me out of sticks and fishing line. Grace is on a similar excursion, but it’s serious—early morning darkness, actual worms for bait. She’s nervous, but then finds a creative way to overcome her fears and actually hook her very own fish. It’s a lovely book about family connections, with appealing illustrations.

We like Fire Pie Trout by Melanie Mosher and Renne Benoit, published by Aboriginal Publishers, Fifth House. I like it because I have memories of going “fishing” with my grandfather when I was little, the fishing rods he made me out of sticks and fishing line. Grace is on a similar excursion, but it’s serious—early morning darkness, actual worms for bait. She’s nervous, but then finds a creative way to overcome her fears and actually hook her very own fish. It’s a lovely book about family connections, with appealing illustrations.

It is possible that with Goodnight, You, the fourth of her Piggy and Bunny books, Genevieve Cote has written (and illustrated!) her finest yet. It’s a clever book in which the two friends on a camping trip confront their very different fears, and find helpful ways to support each other. I am particularly impressed with how Cote uses the friends’ tent as a shadow backdrop, the shapes they make essential to the stories they tell one another, providing an extra layer of meaning to the illustrations and text.

It is possible that with Goodnight, You, the fourth of her Piggy and Bunny books, Genevieve Cote has written (and illustrated!) her finest yet. It’s a clever book in which the two friends on a camping trip confront their very different fears, and find helpful ways to support each other. I am particularly impressed with how Cote uses the friends’ tent as a shadow backdrop, the shapes they make essential to the stories they tell one another, providing an extra layer of meaning to the illustrations and text.

Spic and Span: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen by Monica Kulling is the latest in the “Great Ideas” series of picture book biographies, and my favourite yet. Gilbreth is well-known as the mother of eleven children in the family celebrated in the book and films, Cheaper by the Dozen. But she was also a psychologist, a leading efficiency expert, industrial engineer, an author, a professor, and an inventor. Her inventions included the electric mixer, and the compartments you use every day in the door of your fridge, and Kulling depicts her life in wonderful detail here. You can read my interview with Monica Kulling at 49th Shelf.

Spic and Span: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen by Monica Kulling is the latest in the “Great Ideas” series of picture book biographies, and my favourite yet. Gilbreth is well-known as the mother of eleven children in the family celebrated in the book and films, Cheaper by the Dozen. But she was also a psychologist, a leading efficiency expert, industrial engineer, an author, a professor, and an inventor. Her inventions included the electric mixer, and the compartments you use every day in the door of your fridge, and Kulling depicts her life in wonderful detail here. You can read my interview with Monica Kulling at 49th Shelf.

Sam and Dave Dig a Hole by Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen is so weird and so fantastic. Confession: I have a knack for missing the essential details in Klassen’s illustrations, and therefore the point of the stories have to be pointed out me after the fact. Though the point itself is really a elusive here anyway, and no amount of rereading has brought us any closer (it’s as mysterious as whatever woke up Mickey in The Night Kitchen and gave him cause to holler, “Quiet down there!”), but we keep reading anyway, because of the little jokes in Klassen’s pictures, and because of the dog and the cat and their sideways glances. I don’t love this one quite as much as I loved their previous collaboration, Extra Yarn, but that’s a tall order, and this book does something very different, which is admirable too.

Sam and Dave Dig a Hole by Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen is so weird and so fantastic. Confession: I have a knack for missing the essential details in Klassen’s illustrations, and therefore the point of the stories have to be pointed out me after the fact. Though the point itself is really a elusive here anyway, and no amount of rereading has brought us any closer (it’s as mysterious as whatever woke up Mickey in The Night Kitchen and gave him cause to holler, “Quiet down there!”), but we keep reading anyway, because of the little jokes in Klassen’s pictures, and because of the dog and the cat and their sideways glances. I don’t love this one quite as much as I loved their previous collaboration, Extra Yarn, but that’s a tall order, and this book does something very different, which is admirable too.

Julia’s House for Lost Creatures by Ben Hatke: You already know that we’re Zita-mad, so when we learned that her creator was publishing his first picture book, we pre-ordered it immediately. And we loved it when we finally got it—it has all the mystery, magic and power of Zita. It’s a story whose illustrations show tiny doors in the wall to mysterious places, and the story itself comes with similar mystery. Like Zita too, this story of a girl with a house of her own (on a turtle’s back, no less) is about female empowerment, friendship and finding one’s way home.

Julia’s House for Lost Creatures by Ben Hatke: You already know that we’re Zita-mad, so when we learned that her creator was publishing his first picture book, we pre-ordered it immediately. And we loved it when we finally got it—it has all the mystery, magic and power of Zita. It’s a story whose illustrations show tiny doors in the wall to mysterious places, and the story itself comes with similar mystery. Like Zita too, this story of a girl with a house of her own (on a turtle’s back, no less) is about female empowerment, friendship and finding one’s way home.

November 12, 2014

Toronto International Book Fair

I’m excited to be attending the Toronto International Book Fair this weekend, an event that is packed with all the very best of bookish things. On Saturday and Sunday, I will be helping to work 49th Shelf’s booth (where we’ll be giving out kisses of the chocolate kind, and giving you great ways to get involved with our site and win prizes) and also hosting events by authors Catherine Gildiner and Lesley-Ann Scorgie. It’s going to be excellent. Do come and say hi!

November 10, 2014

Commemoration serves a political agenda

“Commemoration serves a political agenda, where nations adopt a single story that comes to represent past wars, constructed to uphold a version of the story that allows a nation to maintain a positive perception of its past. In the absence of multiple voices all speaking their own stories, nuance and contradiction are subsumed under an authoritative narrative.” –Carol Acton, “Lest We Forget: War and Memory in the 21st Century” , TNQ 131

“Commemoration serves a political agenda, where nations adopt a single story that comes to represent past wars, constructed to uphold a version of the story that allows a nation to maintain a positive perception of its past. In the absence of multiple voices all speaking their own stories, nuance and contradiction are subsumed under an authoritative narrative.” –Carol Acton, “Lest We Forget: War and Memory in the 21st Century” , TNQ 131

I renewed my subscription to The New Quarterly in July, but something went amiss (in particular: my ability to follow up on things) and so only just today did I receive my copy of TNQ 131 whose theme is “War: An Uphill Battle.” But I’m glad about that, because I think I’ve been looking for this exact read as we head into another Remembrance Day, a day that overwhelms me because I think about it oh so much. Though you mightn’t think so—I don’t wear a poppy. But not for thoughtlessness, no. Rather, I am so uncomfortable with the authoritative narrative, which seems to have become even more heightened since a mentally-ill man with a gun charged through Ottawa last month and murdered another man who was a soldier. Some might explain this as the soldier having given his life for us, which doesn’t make any sense. I am also so troubled by how war devastates soldiers’ mental and physical health—it’s as bad for them as it is for anyone. I learned about war from my grandfathers, who were both quite adamant that there should never be another one, that no human being should have to go through that. And they knew what they were talking about.

I’ve only just started reading TNQ, but am already finding it enthralling—in particular Ayelet Tsabari’s essays about her experiences in the Israeli army and growing up under the threat of war, how those experiences formed the person she’d become. A piece by journalist May Jeong about her experiences reporting from Afghanistan. (She writes, “If we are serious about bringing women’s rights to the this country, we have to end the war first.”) Stories and reflections on war and conflict, by writers including Kevin Hardcastle and Tamas Dobozy. The essay, “Mud” by the brilliant Rachel Leibowitz. “Look, Don’t Look” by Diana Fitzgerald-Bryden, on what violent and graphic images do to those of us who watch them. And Karen Connelly’s “#ItEndsHere” on the war(s) on women, along with poems from her latest book, Come Cold River. So many voices, so much nuance and contradiction. It’s a really stunning issue. I’m glad to have finally received it.

So what to do then when you’re a person who won’t wear a poppy, but who wants your daughters to remember the brutal, thankless war their great-grandfathers fought, and one before it in which their great-great-grandfather died. When you’re allergic to sentiment and glorification, you think that death doesn’t make one a hero and also that all this death and injury is such a waste, and you understand the ramifications of Canada having abandoned its role as a peacekeeper. Well, instead of a moment of silence, we talk and talk, and ask questions, and point out contradictions, and reflect, and we read, and we learn.

I am very pleased with the new picture book, Bunny the Brave War Horse, by Elizabeth MacLeod and Marie Lafrance, which doesn’t glorify war at all or mask its ugliness, but won’t terrify young readers either. When a soldier dies in the book, no one suggests it was worth it. But the story keeps the memory of WW1 alive, and we can strengthen the connection by pointing out that that it was really not so long ago. There is nuance here, the soldier thinking to himself that the battlefield (with its poppies) must have been a beautiful place before it was wracked and scarred by war.

I am very pleased with the new picture book, Bunny the Brave War Horse, by Elizabeth MacLeod and Marie Lafrance, which doesn’t glorify war at all or mask its ugliness, but won’t terrify young readers either. When a soldier dies in the book, no one suggests it was worth it. But the story keeps the memory of WW1 alive, and we can strengthen the connection by pointing out that that it was really not so long ago. There is nuance here, the soldier thinking to himself that the battlefield (with its poppies) must have been a beautiful place before it was wracked and scarred by war.

I also appreciate the book In Flanders Fields by Linda Granfield, which was first published in 1995 and has just been reissued. Harriet is too young for all the biographical details about John McRae and his poem, but we read the poem itself last night, accompanied by the stirring illustrations, and it made me cry. (It is possible that I so allergic to sentiment because I am particularly susceptible to it.) Yes, it’s definitely part of that authoritative narrative, which would suggest that I have indeed broken faith with those who died, but I haven’t, and neither do I wish current Canadian forces troops anything but “support”, whatever that means. Except what it means has been hijacked, and it’s all very hard, and awful and (really) unnecessary. It is.

I also appreciate the book In Flanders Fields by Linda Granfield, which was first published in 1995 and has just been reissued. Harriet is too young for all the biographical details about John McRae and his poem, but we read the poem itself last night, accompanied by the stirring illustrations, and it made me cry. (It is possible that I so allergic to sentiment because I am particularly susceptible to it.) Yes, it’s definitely part of that authoritative narrative, which would suggest that I have indeed broken faith with those who died, but I haven’t, and neither do I wish current Canadian forces troops anything but “support”, whatever that means. Except what it means has been hijacked, and it’s all very hard, and awful and (really) unnecessary. It is.

An uphill battle, indeed.

However one remembers, though, the point is just not to forget, and I haven’t. I won’t.

November 9, 2014

Mr. Jones by Margaret Sweatman

So on Thursday night, I was at the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards, sitting up the in the balcony (because the seats on the main floor had been filled while we were still out in the lobby getting that one last glass of wine), and the program was great—wonderful books celebrated, Shelagh Rogers was the host—but there I was reading a novel. Which is a shameful confession, as usual, my complete and utter failure to be in the moment, but what you have to understand about the moment was that I was on the final 100 pages of Margaret Sweatman’s Mr. Jones. A spy novel, no less, intrigue upon intrigue—and upon even more intrigue by that final stretch. How was I supposed to be doing anything else? And something more to understand: this isn’t a small book. A 500 page thick hardback, and I brought it in my purse. Which tells you everything, really. Mr. Jones is an electric, compelling, scintillating read.

So on Thursday night, I was at the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards, sitting up the in the balcony (because the seats on the main floor had been filled while we were still out in the lobby getting that one last glass of wine), and the program was great—wonderful books celebrated, Shelagh Rogers was the host—but there I was reading a novel. Which is a shameful confession, as usual, my complete and utter failure to be in the moment, but what you have to understand about the moment was that I was on the final 100 pages of Margaret Sweatman’s Mr. Jones. A spy novel, no less, intrigue upon intrigue—and upon even more intrigue by that final stretch. How was I supposed to be doing anything else? And something more to understand: this isn’t a small book. A 500 page thick hardback, and I brought it in my purse. Which tells you everything, really. Mr. Jones is an electric, compelling, scintillating read.

Ok, it’s 500 pages, but these are small pages—perhaps a bit too small? 500 narrowish pages are tough to get a grip on, so I dropped the book a few times. It was hard to hold open with my feet. (Does this count as legitimate criticism?) Apart from these niggling details, the book is of stunning design, so gorgeous. Check out the end papers. The prose just as appealing from an aesthetic point of view, all comma splices and curious sentences. The effect of the book as a whole slightly dizzying, as perspective moves 360 degrees, from character to character, but only in pieces. We never see it all at once until it all comes together at the end. Hence the last 100 pages, and my furtive reading in the auditorium balcony in the dark.

Ok, it’s 500 pages, but these are small pages—perhaps a bit too small? 500 narrowish pages are tough to get a grip on, so I dropped the book a few times. It was hard to hold open with my feet. (Does this count as legitimate criticism?) Apart from these niggling details, the book is of stunning design, so gorgeous. Check out the end papers. The prose just as appealing from an aesthetic point of view, all comma splices and curious sentences. The effect of the book as a whole slightly dizzying, as perspective moves 360 degrees, from character to character, but only in pieces. We never see it all at once until it all comes together at the end. Hence the last 100 pages, and my furtive reading in the auditorium balcony in the dark.

It’s a period piece, the spy novel ala Graham Greene, Our Man in Havana. Emmett Jones is Canadian, a World War Two Bomber Commander disillusioned by his wartime deeds and adrift in post-war Toronto. Attending university, he finds himself attracted to John Norfield, a charismatic figure with Communist sympathies, in which Emmett too becomes embroiled, partly out of a need to belong to something, and because of how he is drawn to Norfield (and Norfield’s sometime girlfriend, Toronto deb Suzanne).

We first meet Jones in 1953, a civil servant in External Affairs, post-Gouzenko and the Cold War (and McCarthy) heating up, and he’s under investigation with the RCMP for possible Communist connections. Emmett is now married to Suzanne, with a young daughter, and Norfield is a distant figure in their past—or so the Jones’ pretend as they attempt an idyllic 1950s life. But there are complications. Jones had fathered a son in Japan, where he was stationed in the late 1940s, and his own background (born and raised to Canadians in Japan) makes him a mysterious figure in the Civil Service, particularly as troubles in Vietnam are beginning and all things Oriental are viewed with suspicion (Asia seemingly a monolith vulnerable to to a Communist sweep). Suzanne too has trouble fitting into a cookie-cutter life, her subversive photography revealing her interests in a way that won’t necessarily be helpful for her husband’s career.

And there are other matters we see, as Sweatman moves us back and forth in time, through the 1940s and 1950s, when politics were complicated and nothing was ever quite as it seemed. There is no whole truth, we begin to understand, but only parts of a truth, and they come together to form a puzzle whose final pieces are harrowing and powerful. A Cold War spy novel with a Canadian bent—and a beautiful one to boot. A rare bird after all, Mr. Jones is, just like Jones himself is, perplexing, enigmatic, mysterious, and so intriguingly aloof.

November 6, 2014

Five Star

Today I was quite thrilled to find my recent post, “On Uncertainty, Mistakes and Accidental Cake” included on Elan Morgan’s Five Star Blog Roundup. I was thrilled because this was some great company, writing-wise, but also because of how the Five Star Roundup reminds us that we are all readers online, as well as writers, and that there is a whole world of thoughtful writing out there to explore. So do check out the roundup, this week and every week, and many thanks to Elan for including me, and for all her work fostering community and action online.

Today I was quite thrilled to find my recent post, “On Uncertainty, Mistakes and Accidental Cake” included on Elan Morgan’s Five Star Blog Roundup. I was thrilled because this was some great company, writing-wise, but also because of how the Five Star Roundup reminds us that we are all readers online, as well as writers, and that there is a whole world of thoughtful writing out there to explore. So do check out the roundup, this week and every week, and many thanks to Elan for including me, and for all her work fostering community and action online.

November 6, 2014

The Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards

Such a wonderful celebration of books tonight at the Carlu in Toronto as we celebrated some of the best in Canadian children’s books. Obviously, I am thrilled because Julie Morstad’s How To won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award, and I am a Julie Morstad disciple.As I wrote in my review last year, “The premise is unbelievably clever, but How To‘s genius lies in its simplicity. I love the substance behind its charm as well, that the text is posing and the illustrations are answering such fundamental questions. “How to be happy” is the book’s final statement, accompanied by a two-page spread of children dancing, moving and being together. It’s a lesson as perfect as it is profound.”

Such a wonderful celebration of books tonight at the Carlu in Toronto as we celebrated some of the best in Canadian children’s books. Obviously, I am thrilled because Julie Morstad’s How To won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award, and I am a Julie Morstad disciple.As I wrote in my review last year, “The premise is unbelievably clever, but How To‘s genius lies in its simplicity. I love the substance behind its charm as well, that the text is posing and the illustrations are answering such fundamental questions. “How to be happy” is the book’s final statement, accompanied by a two-page spread of children dancing, moving and being together. It’s a lesson as perfect as it is profound.”

Another contender for the Marilyn Baillie Prize was Where Do You Look? by Marthe Jocelyn and Nell Jocelyn, which we have out of the library at the moment and I just keep renewing. A fabulous puzzle of a book that is, as with any book by M. Jocelyn, a visual treat, but which also points towards the puzzles of language and the complexity of the world, which is the lesson I want to teach my children before almost any other. This book does the trick, and it’s also fun. I think we’re going to have to pick up our own copy…

Another contender for the Marilyn Baillie Prize was Where Do You Look? by Marthe Jocelyn and Nell Jocelyn, which we have out of the library at the moment and I just keep renewing. A fabulous puzzle of a book that is, as with any book by M. Jocelyn, a visual treat, but which also points towards the puzzles of language and the complexity of the world, which is the lesson I want to teach my children before almost any other. This book does the trick, and it’s also fun. I think we’re going to have to pick up our own copy…

Another book we have out of the library that I’m not going to have to purchase is The Man With the Violin by Kathy Stinson and Dušan Petričić, because it took the top prize tonight and everybody in attendance received a copy to take home. And I’m thrilled, because I love this one, based on a true story about violin virtuoso Joshua Bell who played in a Washington DC subway one day, and nobody noticed. Stinson tells the story from the perspective of a small boy who longed to stop to listen, and the story’s amazing power lies in Petričić’s illustrations which really do draw sound, and also highlight the amazingly different ways that adults and children perceive the world. A most deserving winner for sure.

Another book we have out of the library that I’m not going to have to purchase is The Man With the Violin by Kathy Stinson and Dušan Petričić, because it took the top prize tonight and everybody in attendance received a copy to take home. And I’m thrilled, because I love this one, based on a true story about violin virtuoso Joshua Bell who played in a Washington DC subway one day, and nobody noticed. Stinson tells the story from the perspective of a small boy who longed to stop to listen, and the story’s amazing power lies in Petričić’s illustrations which really do draw sound, and also highlight the amazingly different ways that adults and children perceive the world. A most deserving winner for sure.

I was also pleased that my friend Andrew Larsen’s In the Tree House took the Readers’ Choice Award, in particular because I remember him once telling me how his son had told him that his books weren’t funny enough for kids to pick. And now Andrew can say, HA! I love In the Tree House, whose story touched me so much and continues to as I’ve read it over and over again. It’s a book for the ages. So wonderful to see it celebrated tonight. With so many others too—books by Isabelle Arsenault, Ruth Ohi, Erin Bow, and more! It was a really wonderful evening with triumph after triumph.

I was also pleased that my friend Andrew Larsen’s In the Tree House took the Readers’ Choice Award, in particular because I remember him once telling me how his son had told him that his books weren’t funny enough for kids to pick. And now Andrew can say, HA! I love In the Tree House, whose story touched me so much and continues to as I’ve read it over and over again. It’s a book for the ages. So wonderful to see it celebrated tonight. With so many others too—books by Isabelle Arsenault, Ruth Ohi, Erin Bow, and more! It was a really wonderful evening with triumph after triumph.

Canadian children’s publishing is a powerful force, and it’s an honour to be a small part of it.

Also see the nominees’ Seeds of a Story at 49th Shelf.

November 4, 2014

Short Cuts: Hilary Mantel and Martha Baillie

Could I have chosen a better book to pick up on Halloween than Hilary Mantel’s new short story collection, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher? Just check out that cover? And no surprise that ghosts pervade the stories in the book, since this is the author of Beyond Black. A woman whose memoir was called Giving Up the Ghost after all (though she hasn’t altogether). I am just a bit Hilary Mantel mad, but I can’t bear enormous historical novels, and so I was quite thrilled about this new book, contemporary Hilary Mantel, the kind I like the very best. And the stories were terrific, the writing exquisite. Lines like, “Then her hands opened. The floor was limestone and the glass exploded.” What writer would set it up that way? Mantel is so smart, so sly. Such deviousness. I love her. Oliver Cromwell, I could take him or leave, but Hilary Mantel in the here and now.

Could I have chosen a better book to pick up on Halloween than Hilary Mantel’s new short story collection, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher? Just check out that cover? And no surprise that ghosts pervade the stories in the book, since this is the author of Beyond Black. A woman whose memoir was called Giving Up the Ghost after all (though she hasn’t altogether). I am just a bit Hilary Mantel mad, but I can’t bear enormous historical novels, and so I was quite thrilled about this new book, contemporary Hilary Mantel, the kind I like the very best. And the stories were terrific, the writing exquisite. Lines like, “Then her hands opened. The floor was limestone and the glass exploded.” What writer would set it up that way? Mantel is so smart, so sly. Such deviousness. I love her. Oliver Cromwell, I could take him or leave, but Hilary Mantel in the here and now.

Or at the least in the early 1980s, moments before Thatcher meets her fate: “Who has not seen the door in the wall?… [N]ote the door: note the wall: note the power of the door in the wall that you never saw was there. And note the cold wind the blows through it, when you open it a crack. History could always have been otherwise…”

*****

Another weird and wonderful book is The Search for Heinrich Schlogel by Martha Baillie, whose Giller-nominated The Incident Report was one of my favourite books of 2009. The new novel comes from a similarly curious sensibility, seemingly created by an archivist with uncanny access to the materials comprising the life of Schlogel, a man who is unremarkable in a number of ways, except that he slips through a hole in time while hiking through the Arctic in 1980, and reemerges 30 years later. Not to even any real end either, and he keeps slipping through our archivist’s fingers (and our own). I enjoyed the book, though also found it at a distance (as it was meant to be), but was compelled throughout the narrative by the strangeness and Baillie’s beautiful writing. It left me baffled, but cast a spell.

Another weird and wonderful book is The Search for Heinrich Schlogel by Martha Baillie, whose Giller-nominated The Incident Report was one of my favourite books of 2009. The new novel comes from a similarly curious sensibility, seemingly created by an archivist with uncanny access to the materials comprising the life of Schlogel, a man who is unremarkable in a number of ways, except that he slips through a hole in time while hiking through the Arctic in 1980, and reemerges 30 years later. Not to even any real end either, and he keeps slipping through our archivist’s fingers (and our own). I enjoyed the book, though also found it at a distance (as it was meant to be), but was compelled throughout the narrative by the strangeness and Baillie’s beautiful writing. It left me baffled, but cast a spell.

November 2, 2014

On Uncertainty, Mistakes, and Accidental Cake

Tomorrow night in my blogging course, we will be discussing Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Woolf’s Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable”, which really might be one of my favourite pieces of writing ever, and whose wisdom is remarkably applicable to blogging, as well as to life itself. “To me, the grounds for hope are simply that we don’t know what will happen next, and that the unlikely and the unimaginable transpire quite regularly.”

Tomorrow night in my blogging course, we will be discussing Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Woolf’s Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable”, which really might be one of my favourite pieces of writing ever, and whose wisdom is remarkably applicable to blogging, as well as to life itself. “To me, the grounds for hope are simply that we don’t know what will happen next, and that the unlikely and the unimaginable transpire quite regularly.”

So I’ve been rereading the essay, following its twists and turns (and thinking about how much the public streets walked by Woolf’s narrator in “Street Haunting” can stand in for the blogosphere, “a form of society that doesn’t enforce identity but liberates it, the society of strangers, the republic of the streets, the experience of being anonymous and free that big cities invented”).

And then there was an excursion to Kensington Market to purchase not a pencil, but boots for the grown-ups in our family, because the shop there that caters to Portuguese construction workers is the best place we know to buy new Sorels. This was yesterday, and we’d woken up to flurries, so it seemed essential that we buy boots immediately. Plus while in the market, we’d get to pick up wood-smoked bagels and sausages from Sanagans for our evening meal. Once the boots were bought, Stuart with stroller was sent on the bagel errand, while Harriet and I took a quick diversion into Good Egg to scope out potential birthday presents for him.

Where I found this book, Maira Kalman’s The Principles of Uncertainty, based on her illustrated New York Times column. I’d never read the column, but I had been reading Solnit’s essay, which references Kalman’s work, her art, this book. And here was the book in my hands, so I had to have it. I came out of the shop with a stack of books, but pleased with myself. “Only one of these is for me.”

When I got home and went through the Solnit essay again, however, I found that I’d been mistaken. While a section of “Woolf’s Darkness” indeed shares a title with Kalman’s book, Solnit doesn’t mention Kalman at all. I’d made the whole thing up. I’d bought the book by accident. Which was kind of interesting to me, because I am so interested in the connections between books, how they speak to one another, and now I’m fascinated too by the idea of the mistaken allusion, the connection that was never there at all. But now it is, because I supposed it was. Our reading lives are such a tangled web.

All was not lost though. While Kalman’s book was far from Solnit’s essay (though for me, the two shall be linked forevermore—and they’re actually interesting companions), the book was wonderful. It was as though my mistaken allusion had been a trick to get The Principles of Uncertainty into my hands, where it had belonged all the while.

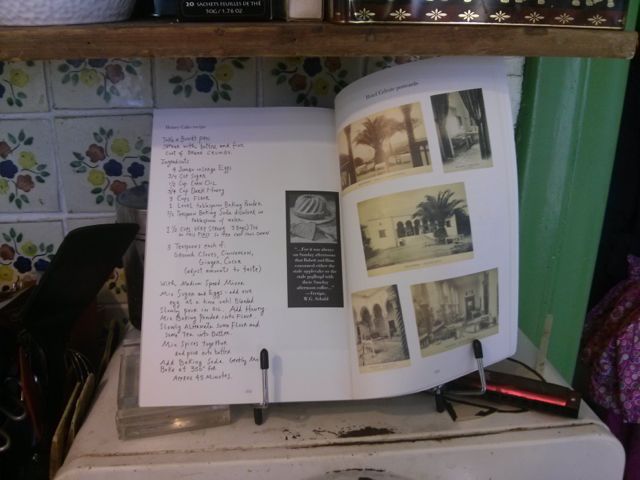

Full of gorgeous images, funny stories, curious questions, and delightful things. It has an index, as all the best books do, and an appendix with images of postcard collections (one of postcards with waterfalls), collected food packets, a list of all the characters in The Idiot by Dostoevsky, and the family recipe for the honey cake referenced on page 54:

“The kitchen is small, spare and shiny. We drink tea an eat honey cake in the hot stillness of the afternoon.”

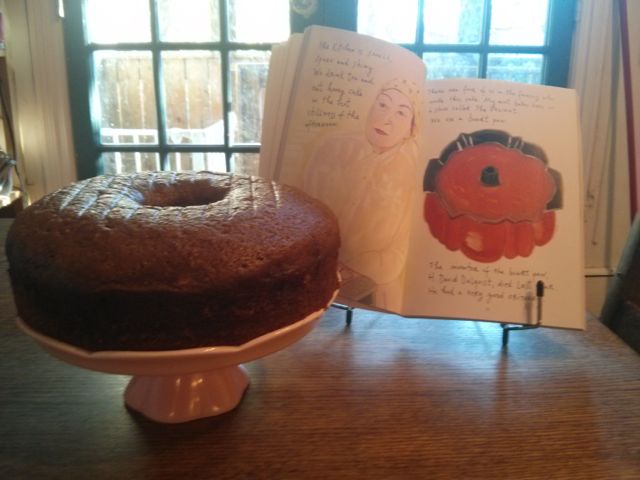

This afternoon, I baked that cake with Harriet, because today had an extra hour within and there was space for such a thing. We had to borrow a bundt pan from our neighbour, Sarit, because we don’t have a bundt pan even though I thought we did. It seems there is no limit to what I’m capable of remembering wrong.

We had a good time baking—it is much less frustrating baking with Harriet now than when she was three and compelled to stick her hands in the batter (and she sneezes in the bowl hardly ever now). I explained to her that we were making a cake from the book that I had bought by mistake, and it’s that a wonderful thing about the universe—that an accidental book can lead to cake in the oven on a sunny afternoon:

“And then the all-clear sounded and people returned, hope undiminished. They returned, so elegant and purposeful to the books. / What does this have to do with bobby pins and radiators and kokoshniks? One thing leads to another.”

Then when we were all done, I proceeded to TWICE pick up the bundt pan (which was constructed of two parts) incorrectly, separating the bottom from the sides and batter seeping out onto the table. (“I heard at least two ‘fucks,'” Stuart inquired after. “What went wrong?”) As I spatula’d up the mess, Harriet patiently parroted what I’d been saying to her about the accidental book as we’d baked, that sometimes mistakes lead us in the most interesting directions.

“I don’t know if it’s quite the same with baking,” I confessed, sorry that everything was not so poetic, but perhaps it is, or it’s just that this cake is forgiving, because it was, and the cake was wonderful. Delicious, moist, and a perfect balance of spice and sweet. One thing leading to another indeed, and what good fortune when the thing one’s being led to is cake.