September 22, 2014

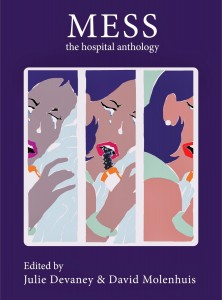

Mess: The Hospital Anthology

I was born in a hospital, and then spent about 30 years not being in the hospital, save for visits to the ER for various frivolous things. And then I started having babies, and a benign growth on my thyroid, and my friends had babies and my dad was treated for cancer, and it seems that hospitals are no longer unchartered territory in my personal geography. Last week, I visited specialists at no less than two of them. And this familiarity was part of the reason I’ve been looking forward to reading Mess: The Hospital Anthology, edited by Julie Devaney (author of the acclaimed My Leaky Body) and David Molenhuis.

But my interest is for the book’s less familiar elements too. I wanted to read about death. And not because I wanted to exactly, but because I am so uncomfortable with how unfamiliar I am with experiences of death and dying, unsurprisingly because, as one writer notes in the book, there is a tendency for doctors and patients alike to dance figure-eights around these ideas rather than saying what they mean. Though it’s not just death—a reluctance to talk about any of the messy bits of bodies and healthcare means that death is actually the most concrete idea we come to associate with hospitals, resulting in much fear and discomfort associated with these places.

The third reason I was interested in this book were the literary reputations of its contributors: poems by Jacob Scheier, Priscila Uppal, Jennica Harper; pieces by Tabatha Southey, Stacey May Fowles, S. Bear Bergman, Diane Flacks, Micah Toub, Sarah Leavitt, Shannon Webb-Campbell and others. One comes to anthologies with an agenda, but the pieces stay with the reader for their writing, and they do here, and not just in the pieces by names I recognized.

The anthology opens with Southey’s essay on her experiences giving birth to her first child on Christmas Eve, a birth whose processes go awry for a time, making its author most aware of the enormous range of human experience enacted all the time within a hospital’s confines, a range the entire book goes to illuminate: birth, death and everything in between. Each section of the book is prefaced by a short piece by Devaney, sections from an essay about a season in her life that was rife with experiences of birth and mortality, mostly the latter. Many of the pieces in the section about death reflect a tendency to leave thinking about it until the last possible moment, to focus on all possible alternatives except the ultimate one. They also show the various ways family members grieve, how these emotions rub up hard against those from medical professionals, the ways in which the dying and their loved ones are failed by the medical establishment at the end of life. How very hard it is to be prepared for death, no matter how many anthologies a reader might explore.

Other pieces reflect the tender humanity taking place in hospitals all the time, how mental health patients are particularly compromised, how hospital stories connect with wider societal issues, what it feels as a person to be reduced to no more than another body in the medical system, and how bodies are stranger and more mysterious than even doctors understand. I particularly appreciated Diane Flacks’ “Pray Tell (or How I Became an Atheist at Sick Kids Hospital)”, a powerful refutation to that cliche about gods only giving you what you can handle. Jane Eaton Hamilton on her experiences photographing deceased infants with their families is also a beautiful and striking piece. David Molenhuis’ essay about the death of his mother, the callousness of the medical professionals who failed her and the hole her loss has left in their family life should be required regular reading for doctors everywhere.

Mess is a little bit messy, which is not unfitting. The range of topics considered seemed a bit too wide, a few pieces not quite belonging, or only tangentially. I also would have welcomed a few more pieces from medical professionals themselves, though maybe asking these to be as well-written as the writers’ pieces is too large a request—if they were writers, they probably wouldn’t be doctors or nurses. But overall, the effect of the book is most powerful. Devaney has made her reputation as a patient advocate, illuminating the human side of life on the gurney, which is perhaps where life is at its most life-ist anyway. With Mess, Devaney and Molenhuis have shone a spotlight where many of us still fear to tread, doing patients an enormous service in illuminating their experiences with the potential of changing our healthcare system for the better, and also creating an emotional and most compelling read.