July 26, 2013

Happy Summer

You know as well as I do that we seem to be on a permanent vacation lately (see photo of Harriet at Woodbine Beach last Tuesday) but we’re heading out of town for awhile, and following week is devoted to other projects while Harriet is at day camp. So I will see you in a couple of weeks. Happy Summer!

You know as well as I do that we seem to be on a permanent vacation lately (see photo of Harriet at Woodbine Beach last Tuesday) but we’re heading out of town for awhile, and following week is devoted to other projects while Harriet is at day camp. So I will see you in a couple of weeks. Happy Summer!

July 25, 2013

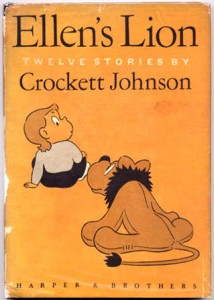

Ellen’s Lion by Crockett Johnson

We go to the library every week or so, and I wander the stacks plucking books off the shelves with never an idea of which will “take”. Most of them are good or okay, some of them we read once and never read again, and then once in a while (and we never know when) there is a book we fall in love with. Ellen’s Lion by Crockett Johnson was such a book, though we came close to missing it altogether. It was small, old battered, and text-heavy, so Harriet never picked it up from the pile. We only started reading it when we learned that someone else had requested the book and therefore we couldn’t renew it, but it quickly became apparent that Ellen’s Lion is a book we had to own.

We go to the library every week or so, and I wander the stacks plucking books off the shelves with never an idea of which will “take”. Most of them are good or okay, some of them we read once and never read again, and then once in a while (and we never know when) there is a book we fall in love with. Ellen’s Lion by Crockett Johnson was such a book, though we came close to missing it altogether. It was small, old battered, and text-heavy, so Harriet never picked it up from the pile. We only started reading it when we learned that someone else had requested the book and therefore we couldn’t renew it, but it quickly became apparent that Ellen’s Lion is a book we had to own.

Published in 1959 and written and illustrated by Johnson (of Harold and the Purple Crayon fame), Ellen’s Lion is a book it is impossible to imagine that Mo Willems hadn’t been thinking about when he created his wonderful Amanda and her Alligator. The books are so similar in approach and tone, the story of a sparky girl and her strangely animated stuffed toy, dealing with the peculiar power dynamics between them. Though Johnson’s book is a little bit darker, Ellen’s stuffed lion a more complex character than Amanda’s alligator (and not always altogether kind). Johnson also plays interestingly with the fact that the lion’s animatedness is fuelled by Ellen’s imagination only (or is it?). There is a marvelous depth here that recalls what I love best about Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad.

There are few illustrations in the book, so it’s not going to appeal to everybody, but we were drawn in by the remarkable character of Ellen herself (who bears an uncanny physical resemblance to Harold). The book begins with the story “Conversation and Song”, whose opening is:

Ellen sat on the footstool and looked down thoughtfully at the lion. He lay on his stomach on the floor at her feet.

“Whenever you and I have a conversation I do all the talking, don’t I?” she said.

The lion remained silent.

“I never let you say a single word,” Ellen said.

The lion did not say a word…

Finally, the lion talks, and Ellen tries to persuade him to join her in singing a round. Oddly, it doesn’t work. It seems that Ellen and her lion are incapable to singing two different parts at once.

In the other stories, Lion rides on Ellen’s train set all the way to Arabia. Ellen phones the police to report a lion in her room, and then must hide her lion when the (imaginary?) policeman arrives. In “Two Pairs of Eyes”, Ellen uses her lion’s button eyes to look for the things in the dark she can’t see behind her. In “Doctor’s Orders”, Ellen plays doctor and tries to convince Lion that he’s a poor, ill little lion who just can’t stop smoking. Ellen tries to convince the lion that he should be a tiger when he grows up. Ellen’s acting in a play in “Five Pointed Star”, and Lion must resist her efforts to involve him in the performance. In “Sad Interlude”, Ellen tries to project great melancholy onto her lion, but he’s not playing. In “Fairy Tale”, Ellen goes from game to game, imagining she’s a fairy, then a knight, then a princess, without transitions even, all the while she is eating a muffin with raspberry jam. Her imagination is inexhaustible. And in the final story “The Last Squirrel”, a new toy threatens to displace Ellen’s Lion, but the history between girl and plush creature proves a bond too strong to sever.

There is one moment, or one word, only when this book shows its datedness. “I’m going to be a lady fireman,” Ellen shouts as she explains to lion that he’s going to be a tiger when he grows up, not her. But even the sentiment of this demonstrates the kind of book that Ellen’s Lion is, that Ellen is a strong, feisty and spirited heroine whose gender is incidental to her character (and that’s why I loved Willems’ Amanda too). I might declare that Ellen was ahead of her time, though the fact of the matter is merely that contemporary female picture book characters in general are undergoing a bit of a regression.

I love this book. We bought a used copy from Amazon for a very low price, though it’s also currently in “print” as an e-book. The really cool news, which we discovered yesterday, is that Johnson wrote a sequel to Ellen’s Lion, called The Lion’s Own Story. However this cool news takes a tragic turn–the book is not available at the library and used copies sell for $300. Has anybody read it?

July 24, 2013

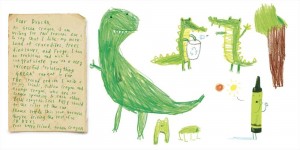

The Day the Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt and Oliver Jeffers

“Down with this sort of thing!” screams the red crayon’s placard on the back of The Day the Crayons Quit, a new book by Drew Daywalt and illustrated by THE Oliver Jeffers. And oh, this book is funny, appealing to the little ones listening and their parents alike. More over, to those of us who are postally inclined: here is an epistolary picture book, illustrations of airmail envelopes even. They’re among a huge stack of envelopes tied up with string that Duncan discovers one day at school when he’s taking out his crayons. It turns out the crayons have quit, however, their letters voicing each of their respective protests: red is sick of the overtime, having to work through the holidays colouring Santa Claus and Valentine hearts; beige hates having everyone think he is boring (“when was the last time you saw a kid excited about coloring wheat?”); grey is exhausted from overuse, with Duncan’s affinity for elephants, hippos and whales, each of them so big; white is barely there; orange and yellow are in a feud about the colour of the sun. And so it goes, letter by letter, colour by letter, until Duncan devises a clever way to bring peace to his crayon box.

“Down with this sort of thing!” screams the red crayon’s placard on the back of The Day the Crayons Quit, a new book by Drew Daywalt and illustrated by THE Oliver Jeffers. And oh, this book is funny, appealing to the little ones listening and their parents alike. More over, to those of us who are postally inclined: here is an epistolary picture book, illustrations of airmail envelopes even. They’re among a huge stack of envelopes tied up with string that Duncan discovers one day at school when he’s taking out his crayons. It turns out the crayons have quit, however, their letters voicing each of their respective protests: red is sick of the overtime, having to work through the holidays colouring Santa Claus and Valentine hearts; beige hates having everyone think he is boring (“when was the last time you saw a kid excited about coloring wheat?”); grey is exhausted from overuse, with Duncan’s affinity for elephants, hippos and whales, each of them so big; white is barely there; orange and yellow are in a feud about the colour of the sun. And so it goes, letter by letter, colour by letter, until Duncan devises a clever way to bring peace to his crayon box.

There is a reference to nakedness and underwear, demonstrating that you can be smart and appeal to the lowest common denominator at the same time, much to my daughter’s amusement. The book is gorgeously illustrated, Jeffers’ familiar collage approach shown here as the pictures include the texture of actual pieces of paper and pages from colouring books. The crayons themselves are simply drawn, but still have enormous personality. The art they’re used to create is charmingly convincing as that made by a childish hand.

Here is a wonderful testament to the hidden lives of ordinary things, as well as to childhood creativity and the pleasures of rainbows.

July 22, 2013

Jumping the Gun

As always, the only prep I ever do before the night before we go away (or morning of, sometimes) is to select my vacations reads. Fingers crossed that Iris is partial to Muskoka chairs. And because 5 books might be a bit ambitious for a holiday with a newborn, I have started my vacation reads a few days in advance. Anyway, there you have it. A mix of fiction and nonfiction, rereads and new. And naturally, some Barbara Pym.

As always, the only prep I ever do before the night before we go away (or morning of, sometimes) is to select my vacations reads. Fingers crossed that Iris is partial to Muskoka chairs. And because 5 books might be a bit ambitious for a holiday with a newborn, I have started my vacation reads a few days in advance. Anyway, there you have it. A mix of fiction and nonfiction, rereads and new. And naturally, some Barbara Pym.

July 22, 2013

“Like life is always fucking subtle”: Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

“I’m going to blog about that.”/ “I knew you’d say that.”

“I’m going to blog about that.”/ “I knew you’d say that.”

I am really excited about the forthcoming anthology Friend. Follow. Text. #storiesFromLivingOnline, which will include short fiction by Canadian authors including Jessica Westhead, Heather Birrell and Alex Leslie, featuring (I suspect…) stories which were some of my favourites from their collection–Westhead’s story that takes place in the comments section of a lifestyle blog; Birrell’s on an online pregnancy forum; Leslie’s comprised of descriptions of Youtube videos featuring a Bieber-like teen-pop sensation. Even Samantha Bernstein’s memoir in emails Here We Are Among the Living is part of this trend of authors using online and social media to change the shape of traditional literary forms, taking advantage of the uniqueness and peculiarity of online communication to contain modernity in their work, to say something new.

At first, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wouldn’t be the most obvious candidate to be part of this literary trend. Her previous novel Half of a Yellow Sun (which won the Orange Prize in 2007) was a sweeping epic novel about the Biafran War. She is the writer who brought me to Chinua Achebe. Adichie is Africa. She is history. Her scope is huge, when online communication can seem so ridiculous and small, so much lesser. And yet, it is also very much of this world, and it is the world that Adichie is concerned with. As she stated in a recent interview, “I love books that are social in the way that they engage with the real reality.”

In her new novel Americanah, Adichie’s protagonist is a blogger. Ifemelu is a Nigerian expat in America who has established herself as author of the blog Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black. She is able to make a living from her blog through advertising and speaking engagements, and has also been made a fellow of Princeton University. Her blog attracts hundreds of readers everyday with such provocative posts as “A Michelle Obama Shout-Out Plus Hair as Race Metaphor”, “Obama Can Win Only If He Remains the Magic Negro” and “Thoughts on the Special White Friend”. For Adichie’s purposes, however, the blog exists so she can include sharply-worded, strongly opinionated, polarizing ideas in her novel about race in America, ideas which have been flooding social media since George Zimmerman’s acquittal last week of murder in the death of Trayvon Martin. The blog posts–humorous, pointed and passionate–read in tone and language as very authentic, and along with the novel’s references to Facebook, email, and an online forum about natural hair, infuse the novel with a fascinating intertextuality. The blog posts in particular give the novel an edginess that straightforward fiction might be too subtle to provide.

Subtlety was an issue for me as I was reading Americanah though. While it was compelling, the story of Ifemelu and Obinze who begin as a couple in high school and each escape the “choicelessness” of life in Nigeria (for the US and UK respectively) to find their lives taking radically different trajectories, there was a hollowness to the secondary characters these two encountered. “Some of the people we met had nothing, absolutely nothing, but they were so happy,” says Ifemelu’s first American employer of a trip to India. She eventually becomes a friend to Ifemelu but also seems to exist primarily as a mouthpiece for other such asinine pronouncements. Where was the depth in these characters, I was wondering, struggling to make sense of its lack in the context of Adichie’s talent as a novelist. Though could this be part of the novel’s satire, I wondered? And if we’re going to turn the tables, is not portraying characters of a certain race as stereotypical stock characters part of an age-old literary tradition?

There was more though. I love a book so textured that the answer to my criticisms are contained inside its very pages. I reached page 335 to find a tirade by Ifemelu’s boyfriend’s sister who is about to publish her first book, a memoir about growing up black in America. She explains, “My editor reads the manuscript and says, “I understand that race is important but we have to make sure the book transcends race…” And I’m thinking, But why do I have to transcend race? You know, like race is a brew best served mild, tempered with other liquids, otherwise white folk can’t swallow it.” Explaining an anecdote, she says, “So I put it in the book and my editor wants to change it because he says it’s not subtle. Like life is always fucking subtle.”

She continues, “You can’t write a novel about race in this country. If you write about how people are really affected by race, it’ll be too obvious. Black writers who do literary fiction in this country, all three of them… have two choices: they can do precious or they can do pretentious. When you do neither, nobody knows what to do with you. So if you’re going to write about race, you have to make sure it’s so lyrical and subtle that the reader who doesn’t read between the lines won’t even know it’s about race. You know, a Proustian meditation, all watery and fuzzy, that at the end just leaves you feeling watery and fuzzy.”

Blog posts, of course, are the very opposite of lyrical and subtle. Adichie has clearly found a way around the matter.

In some ways, Adichie’s novel bears a resemblance to Zadie Smith’s NW and it’s treatment of race and London, though Adichie shrugs off Smith’s experimental approach, preferring to focus on life as lived as opposed to its voices or the complexities of point of view. The story is the point, and the ideas contained within, instead of its delivery. Ifemelu leaves Obinze when she receives a partial scholarship to an American university, though the two promise to remain connect, to not be apart forever. She arrives in America, however, to discover that the reality of life there is radically different from what she’s seen on The Cosby Show or The Fresh Prince of Bel Air. She must find a job to make ends meet, but she’s not permitted to work legally and has difficulty finding a job under the table as her accent, her appearance, and her lack of American job experience continue to stymy her efforts. She slips into a depression and is just about to hit rock bottom, which would have made this a short book if she’d managed it, when things between to happen for her. In a sense, while Adichie does not portray America or the experience of its immigrants in an easy or flattering light, she does demonstrate that the American Dream is possible, while it is not for Obinze in the UK. Though it must be noted what an exception is Ifemelu–I don’t know if it’s more likely that your average Nigerian immigrant would become a Princeton fellow or a professional blogger. In fact the odds of anyone becoming a professional blogger are unlikely.

Meanwhile, Obinze’s American dreams are dashed in light of the September 11th terrorists attacks, when the US tighten their visa restrictions and make him ineligible for entry. He receives a temporary visa to England through his mother, a university professor, and when his visa expires, he remains in the country, working under the name and number of another man who’s helping himself to a portion of Obinze’s wages. He gets a job cleaning shit off toilets, and then delivering kitchens, performing the tricky maneuvre of always watching his back while trying to look forward and desperately cobble together a better future. (Here, Adiche’s explores the world of London’s underground job market for illegal migrants, as did John Lanchester in his novel Capital with his Zimbabwean traffic warden.) The ticket is an arranged marriage to a woman with an EU passport, which can be brought about with the right amount of cash (although the last time he tried this, they took off with his money). Plans fail, however, and Obinze is deported, brought home in disgrace only to discover that things are changing in Nigeria, that there is opportunity for a bright young man who is willing to play the system.

Meanwhile, Obinze’s American dreams are dashed in light of the September 11th terrorists attacks, when the US tighten their visa restrictions and make him ineligible for entry. He receives a temporary visa to England through his mother, a university professor, and when his visa expires, he remains in the country, working under the name and number of another man who’s helping himself to a portion of Obinze’s wages. He gets a job cleaning shit off toilets, and then delivering kitchens, performing the tricky maneuvre of always watching his back while trying to look forward and desperately cobble together a better future. (Here, Adiche’s explores the world of London’s underground job market for illegal migrants, as did John Lanchester in his novel Capital with his Zimbabwean traffic warden.) The ticket is an arranged marriage to a woman with an EU passport, which can be brought about with the right amount of cash (although the last time he tried this, they took off with his money). Plans fail, however, and Obinze is deported, brought home in disgrace only to discover that things are changing in Nigeria, that there is opportunity for a bright young man who is willing to play the system.

Obinze is established as a big man in Nigeria by the time Ifemelu returns after thirteen years in America, and he is by now married with a child. Neither has ever forgotten the other, though the reasons for their estrangement have become unknown or blurry with time. The stakes for their reunion are high, and in a sense Americanah‘s first 426 pages are just a prelude to this point. Because yes, this is a love story, but it’s a love story with an unabashed agenda, rich and compelling. And while Adichie confesses to not being a fan of experimental literature, it can’t be denied that with her third novel, she has broken new literary ground.

July 17, 2013

Les Ontoulu ne mangent pas les livres

We have to thank my lovely cousin, who is my oldest and one of my dearest friends, for delivering this most remarkable picture book into our life. She’d had enough of waiting for Les Ontoulu ne mengest pas les livres to be translated into English and so gave it to us in its original French, along with her very own English translation alongside. And thank goodness she did–this book is wonderful! It is a story about the Ontoulu family (whose name translates as “Read It All”). Their home is full of literary treasures, and the parents are eager to pass on their love on books to their adorable son Lulu. Because books are their life– the Ontoulu’s read books, write books, collect books, they even eat bo– no! don’t be ridiculous! They’d didn’t eat books!

We have to thank my lovely cousin, who is my oldest and one of my dearest friends, for delivering this most remarkable picture book into our life. She’d had enough of waiting for Les Ontoulu ne mengest pas les livres to be translated into English and so gave it to us in its original French, along with her very own English translation alongside. And thank goodness she did–this book is wonderful! It is a story about the Ontoulu family (whose name translates as “Read It All”). Their home is full of literary treasures, and the parents are eager to pass on their love on books to their adorable son Lulu. Because books are their life– the Ontoulu’s read books, write books, collect books, they even eat bo– no! don’t be ridiculous! They’d didn’t eat books!

But when they do introduce books to wee Lulu, figuring that he will love them as much as they do, he promptly sticks them in his mouth. Apparently they feel so good on his teething gums, and the Ontoulu parents are horrified. “Lulu, in our family we don’t eat books,” they tell him and they take the books away until he’s finished teething.

But the next time they give him a book, he throws it on the floor–he loves the music the book creates as it lands. He draws in his picture books. He tears out the pages of a travel book to make into a kite. And his parents are exasperated, while poor Lulu really doesn’t understand both why they’re so unhappy with him and what’s the big deal about books anyway? They seem to only create problems, and besides, he’s never once managed to get to the end of a story.

One day, however, in an effort to cheer up his Papa who is sick in bed, Lulu opens up a book and begins making up a story of his own. His Papa realizes that of all the literary treasures in their home, the amazing stories that Lulu imagines are the greatest of all of them. He and his wife develop a more playful attitude toward their home library, conceding that books sometimes do indeed make fine building blocks for constructing castles and other splendid unconventional things. And with his parents’ more relaxed approach to the bookish life, Lulu begins to understand their passion and decides that he too is going to become a reader of books, a writer of books, a collector of books and an eater of bo–no! don’t be ridiculous! He’s not going to eat books.

How lovely to read a Canadian picture book in our other official language. Merci, ma cousine!

July 15, 2013

Bobcat by Rebecca Lee

I had only read the first story in Rebecca Lee’s short story collection Bobcat before I’d ordered a copy of her novel from the bookstore. Why, I wondered already, had this collection not been more hyped? Not until it was awarded the Danuta Gleed Award a few weeks back did it really come to my attention. But one story was all it took for me to realize that Lee is a writer approaching mastery of her craft. As significant, I think, as the fact that she received an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop is that she received it 21 years ago. That Lee has had time to grow and develop as a writer so she’s no ingenue, but instead her writing reveals a maturity that is most admirable. Her grasp of these stories was so firm, and her voice so strong that I knew I’d be wanting more of it. I look forward to reading her novel The City is a Rising Tide very soon.

Rebecca Lee’s short stories share the same approach as Sarah Selecky’s, the same intimate first-person narration, close attention to detail that sets these characters as very much of this world (lines like “Lizbet basically knew how to live a happy life, and this was revealed in her trifle–she put in what she loved and left out what she didn’t”)–as well as dinner-party settings and fork on the cover. But on the other side, Lee’s marvelous telescoping endings and ultimate broadness of perspective remind me of the stories in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Interpreter of Maladies. (I think “Bobcat” may join Lahiri’s “The Fifth and Final Continent” as one of my favourite short stories ever.) These stories were written over two decades and accordingly the collection lacks a certain cohesion, except for (and this is significant) the solidity of Lee’s voice.

“One of the things Strandbakken had been struggling to teach us was that a building ought to express two things simultaneously. The first was permanence, that is, security and well-being, a sense that the building will endure through all sorts of weather and calamity. But it also ought to express an understanding of its mortality, that is, a sense that it is an individual and, as such, vulnerable to its own passing away from this earth. Buildings that don’t manage this second quality cannot properly be called architecture, he insisted. Even the simplest buildings, he said, ought to be productions of the imagination that attempt to describe and define life on earth, which of course is an overwhelming mix of stability and desire, fulfillment and longing, time and eternity.” –from “Fialta”

Lacking a certain cohesion (which in a collection this good is less a criticism than a statement of fact), yes, but there are more than a few points in common. Three of these stories take place in academic settings. These are stories written with an awareness of history and not just a general contemporariness. They are filled with allusions and references to actual places, people, and things. Though “Bobcat” is like this least of all, the first story, about a dinner party and so tightly contained within four walls that the effect is claustrophobic until the story’s incredible ending in which the whole thing explodes. A hostess is acutely aware of the inner lives and workings of her dinner guests, so much so that she’s blind to her own destiny. The people in this story are so vivid and real, and the ending was both incredible and heartbreaking. “The Banks of the Vistula” is a 1980s’ Cold War story (“But this was 1987, the beginning of perestroika, of glasnost and views of Russia were changing. Television showed a country of rain and difficulty and great humility, and Gorbachev was always bowing to sign something or other, his head bearing a mysterious stain shaped like a continent one could almost but not quite identify” [and how I love that “almost but not quite…]) about a university student who plagiarizes a linguistics paper from 1950s’ Soviet propaganda.

“Slatland” is a peculiar story about a strange psychologist and his impact on a young patient who returns to him years later looking for him to translate letters her Romanian fiance is writing to a woman whom she suspects is her fiance’s wife. In “Min”, another Midwestern university student travels to still-British Hong Kong and is enlisted with the job of selecting him a wife, as her friend’s diplomat father is being faced with the morally ambiguous task of deporting Vietnamese refugees. In “World Party”, a female professor during the 1970s’ uses her relationship with her (perhaps autistic?) son to decide the future of a male colleague who has been accused of a sexually inappropriate relationship with a student. And the final story is “Fialta”, in which architecture becomes analogous to story-writing and a group of students enrolled in an elite mentorship program fall in and out of love with one another, learn, come of age and of self, and are each uniquely bound to their teacher for better or worse.

July 15, 2013

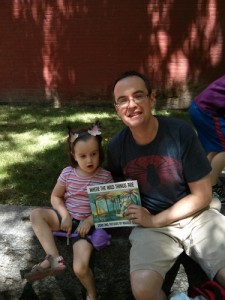

The Wild Rumpus

I learned about Story Mobs on Friday, and knew immediately what we’d be up to the next day. What an adventure: “where great kids’ books meet flash mobs with a dash of Mardi Gras thrown in.” Our family met up with many others in a small park behind Nathan Phillips Square on Saturday afternoon with our maracas on hand, along with wolf ears and a copy of Where the Wild Things Are. Now, we have a newborn in the family and we’re quite crap at organization (wolf ears created 10 minutes before we left the house), so our preparations paled in comparison to those of others who were exquisitely attired and were carrying amazing props. We took part in a rehearsal of the story’s reading, and then made a parade with all the other wild things to the pool in front of City Hall where we drew attention with strange costumes, samba drums, and the general oddness of our presence. The story began, featured readers projecting their voices across the square and the rest of us participating with responses. My favourite part is when we got to shout: “Oh, please don’t go. We’ll eat you up! We love you so.” Though the wild rumpus itself was nothing to be scoffed at as we danced like wild things around Nathan Phillips Square with a bunch of similarly-minded strangers in the sunshine. (The Ai Weiwei sculptures in the pool added nicely to the effect, I think.) And then Max sailed back in and out of weeks to his very own room where his supper was waiting. It was still hot, which deserved a cheer, we thought, and then we scattered, and the event was over as though it had never begun, except for in the minds of those of us who were there.

I learned about Story Mobs on Friday, and knew immediately what we’d be up to the next day. What an adventure: “where great kids’ books meet flash mobs with a dash of Mardi Gras thrown in.” Our family met up with many others in a small park behind Nathan Phillips Square on Saturday afternoon with our maracas on hand, along with wolf ears and a copy of Where the Wild Things Are. Now, we have a newborn in the family and we’re quite crap at organization (wolf ears created 10 minutes before we left the house), so our preparations paled in comparison to those of others who were exquisitely attired and were carrying amazing props. We took part in a rehearsal of the story’s reading, and then made a parade with all the other wild things to the pool in front of City Hall where we drew attention with strange costumes, samba drums, and the general oddness of our presence. The story began, featured readers projecting their voices across the square and the rest of us participating with responses. My favourite part is when we got to shout: “Oh, please don’t go. We’ll eat you up! We love you so.” Though the wild rumpus itself was nothing to be scoffed at as we danced like wild things around Nathan Phillips Square with a bunch of similarly-minded strangers in the sunshine. (The Ai Weiwei sculptures in the pool added nicely to the effect, I think.) And then Max sailed back in and out of weeks to his very own room where his supper was waiting. It was still hot, which deserved a cheer, we thought, and then we scattered, and the event was over as though it had never begun, except for in the minds of those of us who were there.

Another Story Mob is scheduled for two weeks from now with Jillian Jiggs being performed. Thanks to Bunch Family for bringing this fabulous event to my attention!

Another Story Mob is scheduled for two weeks from now with Jillian Jiggs being performed. Thanks to Bunch Family for bringing this fabulous event to my attention!