May 19, 2013

Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Samantha Bernstein

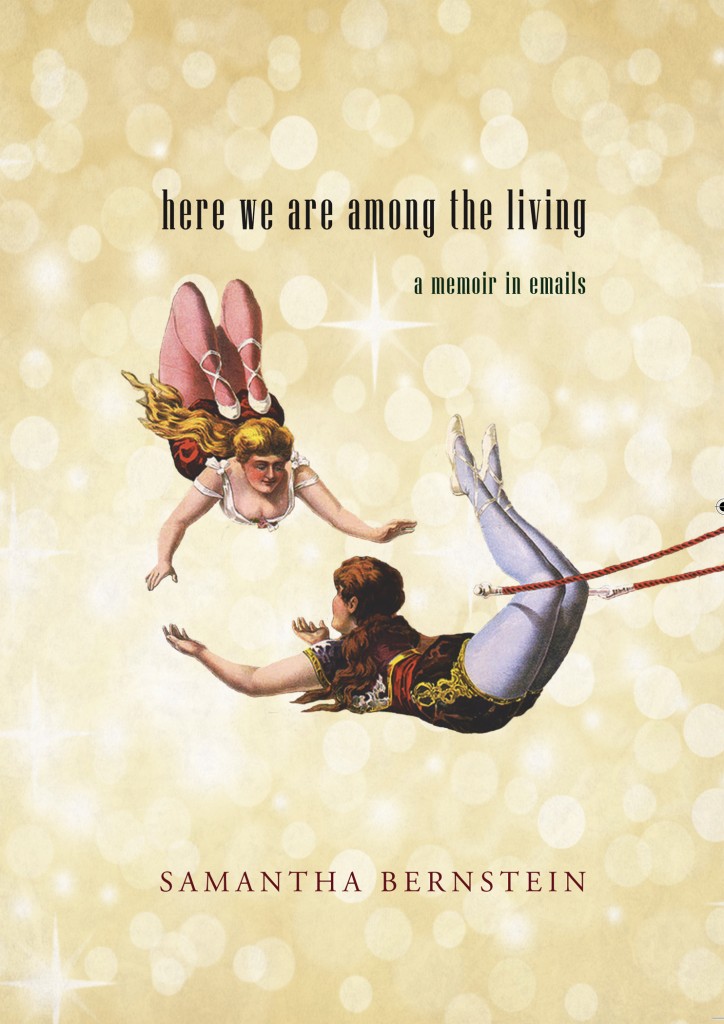

I was introduced to Samantha Bernstein once at an event at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore not long before her memoir Here We Are Among the Living came into the world. When her book was nominated for the BC National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction, one of just three books written by women on a long-list of ten, I knew I had to read it, and it turned out to be one of my favourite books of 2012.

I was introduced to Samantha Bernstein once at an event at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore not long before her memoir Here We Are Among the Living came into the world. When her book was nominated for the BC National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction, one of just three books written by women on a long-list of ten, I knew I had to read it, and it turned out to be one of my favourite books of 2012.

Yes, this is a memoir written by Irving Layton’s daughter, but Bernstein’s literary lineage was less interesting to me than the Toronto she writes about, and her stories of what it was to come of age at the turn of the millennium. I came away from the book wanting to expand on the questions it posed, and so I was very pleased when Bernstein agreed to engage in an email conversation with me.

The following interview was conducted over the past five months, which seems like a long time, but considering it took place between two pregnant women with rich and busy lives, it’s really a wonder that we pulled it off at all.

KC: Did you always know that your memoir was going to be in epistolary format? Why was it important that it was? And were the emails in your book based on actual correspondence?

SB: Yes, I knew from pretty early on that the book would be in emails. I first started working on it during my undergrad in creative writing at York, and my prose assignments started coming out as emails. The idea of writing a book was like a pair of sunglasses I couldn’t take off, but which I felt quite stupid about wearing—Who am I trying to be? and all that. My world at the time was completely tinted by those damn glasses (which, as my mom would tell you, I was super pissed off about much of the time). That need to transcribe everything got funneled into my correspondence with my friends Eshe and Joe; so writing in emails was at first just a less intimidating way to write, because it was familiar and because they presuppose an interested audience.

In my last year of university I read The Sorrows of Young Werther, Goethe’s epistolary novel that sparked rebellion in the hearts of his contemporaries. Werther’s letters, at first, just seem ridiculously whiny and self-indulgent (as twenty-somethings are apt to sound…), but as we discussed the book, the self-narration began to take on a broader significance. The intensity behind Werther’s writing is fueled by the fears of youth, fears of being turned into something you despise, of betraying ideals, of failing to properly appreciate or capture the beauty you are experiencing. And as I learned more about the epistolary form, I liked its history of social engagement and criticism, its continual probing of moral and ethical questions. I felt like it would make sense for this book to be in that tradition. Especially because, as it appeared the book would have to be a memoir, I thought that the epistolary concern with subjectivity—its political implications, its distortions and narcissism—would at least be a formal recognition of the problem of writing about one’s self.

The book is based on actual correspondence, but the letters are almost entirely made up. Some lines are direct from emails I’d sent to Joe and Eshe, and certainly the correspondence we’d had helped me to remember what was going on at the time, and what we’d been thinking about. Thoughts and images from our emails got reworked into the book. I’d also been gathering moments and things people said in notebooks for years. I’ve been surprised, though, at how many people think I just printed out my hotmail folder. If only! But I’m glad the emails are believable. It was hard, sometimes, to keep my late-twenties self from editing my early-twenties self into a less obnoxiously naive/enraged person than I was.

The book is based on actual correspondence, but the letters are almost entirely made up. Some lines are direct from emails I’d sent to Joe and Eshe, and certainly the correspondence we’d had helped me to remember what was going on at the time, and what we’d been thinking about. Thoughts and images from our emails got reworked into the book. I’d also been gathering moments and things people said in notebooks for years. I’ve been surprised, though, at how many people think I just printed out my hotmail folder. If only! But I’m glad the emails are believable. It was hard, sometimes, to keep my late-twenties self from editing my early-twenties self into a less obnoxiously naive/enraged person than I was.

KC: How does email change the epistolary format? Granted, your emails aren’t so cyberish—no emoticons and LOLs. But I imagine the immediacy makes a difference. Does email offer the epistle a boost or does it reduce it?

SB: Oh, that’s a good question! I think it could do both, depending on the correspondents. It would be an interesting study to compare the language in classic epistolary and in what Michael Helm cleverly called e-pistolary novels. Both email and traditional letters express a captivation with the present moment, a need to communicate it to someone who will understand. When the first epistolary novels were being written, the postal system was the amazing new technology! But the immediacy of email does heighten the sense of youthful urgency so often present in the epistolary form; I wanted to capture the intensity of letting those thoughts spill out, usually late at night, knowing my friend would wake to see them, and that I might have a reply by the next night. An email correspondence can feel more like a conversation, I think, which opens interesting possibilities.

When I was twenty, in 2001, email was still a relatively new thing. I don’t think the word emoticon existed yet. We got our first computer when I was fifteen, and I got my hotmail account when I was about eighteen (the one I still have, whose stupid address can be explained by this fact). I’ve often mused with people my age about being the last generation to remember life before the internet, and it may be that our emails reflect this, and cling to the conventions of letter-writing. I also tend to be kind of stodgy about language —I feel like words, not pictures or acronyms, should be doing the work (although I’m not against a smiley face now and again…) But I’m sure there are people are using txt speak and such in creative and interesting ways that will ultimately help to perpetuate the epistle.

KC: What are the connections between your academic self and your writer self? Do your projects tend to overlap and how do they inform one another?

SB: In some ways I feel that academic and non-academic creativity support each other—for instance, I read the wonderful poet Gwendolyn Brooks for a course, and then wrote a sonnet cycle to her. I really felt this interaction as I was editing the book. My doctoral dissertation deals with the ethics of aestheticizing poverty, which is also a strain of the memoir, and the academic thinking helped to structure my edits and bring that theme out more clearly.

As a middle-class person interested in social justice, it’s important, I think, to be aware of how we approach and express our desires to help. When I was younger, this idea was tied up with a lot of frustration around whether my ideals or my friends’ were in any way useful or if they were simply aesthetic choices. I was especially racked by this question because of being raised in the residue of the Baby Boomers’ youth culture, which was a social revolution largely enacted through identity—now a profoundly commercialized aesthetic of “personal freedom,” “rebellion” etc. That was really the question that spawned Here We Are—what happened to the anti-materialist, egalitarian youth movements of the sixties? Were they ever really that? Or was there something inherent in those movements that resulted in the present culture that sells cars with Jimi Hendrix songs (or more recently, Keith Richards hocking Louis Vuitton)? So I did a Master’s at York that allowed me to research youth subcultures, to see how European and North American youth have historically expressed their dissent, and how these traditions intersect with epistolary and life writing. That program at York was amazing luck—I got grants, and so was able to spend the second year of the Master’s basically just writing. A dream, really.

I do feel sometimes, though, that I should choose between academia and literature. Although there are amazing people like Priscila Uppal who gracefully balance the two worlds (and I owe a lot to her teaching), you often hear that it’s one or the other. There are writers like, for instance, Camilla Gibb, who I heard was accepted into some amazing doctoral program and turned it down to write full-time. I worry there won’t be time to do it all, especially now as Michael and I are expecting our first child in the summer. That said, I know I’m not the big-time academic type. I’m not going to be moving around the country for the next ten years in search of tenure. I love teaching—I really still do (most of the time) believe that if you can incite some curiosity in a couple of students, you’ve done a valuable thing. There are so many good and important jobs that help people, for which I am in no way qualified, and teaching is one of the very few professions in which the skills I have can be put to good use. So I just hope to have the privilege of doing that, and continuing to research stuff— because I really like sitting down with a book and a pen, and underlining sentences, and thinking about what I might say about them. And I’m hoping that sometimes that saying will come out in a literary way.

KC: Speaking of youth cultures, that early-twenties self that you document in your book is actually quite a fashionable figure in our pop-culture at the moment, though what I really appreciate about your book is that the young self is a starting point, something to grow (up) from rather than to fetishize in and of itself. Youth is certainly worth examining (and I remember how profound everything seemed when I was 21, how strong was the urge to record every atom as it fell) but for many women, our early twenties are also ourselves at our worst, our most loopy and unhappy. So much gets figured out in the decade that follows, no matter how confused we remain into our 30s. And so I wonder what kind of a feminist gesture is it that society (I’m thinking books and TV shows lately—primarily the show Girls which I can’t bear to watch, fearing it will strike too close to home, reminding me of a self whose existence wasn’t as profound as she imagined she was…) is so focused on the moments before women finally get it together? Can this really be useful?

SB: This is a super interesting question, Kerry. I think it’s really true and important to point out that one’s twenties, exciting as they can be in many ways, are also this weird half-formed time in which one feels far more mature than a few years earlier (high school feels like elementary school in its contained simplicity) but is still essentially blundering around in a miasma of unexplained desires and fears (like, a thicker miasma than in later life…). I was just talking with Joe about this yesterday: how we didn’t know anything in our twenties—and yet, and yet… thinking of how we knew enough to hold onto this friendship despite geographical distance and all the uncertainty of those years, I said we were starting to know something about what we needed to be what we wanted to be.

And maybe that’s what makes this moment such a rich one to represent: we want to capture the sense of self germinating. We’re developing into some form of ourselves that can actually be carried forward, consciously, into our future lives. We are, in many cases, expressing our beliefs very strongly and at least trying to understand them, which, I think, differentiates this process from what happens in our teens, when we start believing things passionately, or identifying with things passionately, but utterly uncritically. In our twenties we start adhering—sometimes just as absurdly—to a critical framework for our actions. The blunders and insights this generates often make for good art.

There was an article in the January 13 New Yorker by Nathan Heller, which I thought was rather lovely on the topic of the twenty-something. He observes the basic continuity of depictions of this age despite recent studies on how current social and economic factors are determining the ways people experience their twenties. He compares a bit of dialogue from Fitzgerald’s 1920 novel This Side of Paradise with a bit from our present Girls, which amazingly demonstrates the continual concern with one’s own mind, with anxiety and self-doubt and how we navigate these in our relationships. Reading Heller’s article made me both happy and slightly sheepish about my book. Sheepish because I am yet another “[a]ble-bodied, middle-class [North] American” (67) documenting the “thrilling sense of nowness” (71) that characterizes the twenties for so many people in that category. Happy, though, to be in this tradition of youths of the modern world—to have documented coming of age in this particular corner of the world that hasn’t been much documented yet, and is interesting in its specificity and its connection to other times and places. And because I captured the wonder of those years as best I could, and am glad to have those moments stashed away.

So to answer your question… I think all good writing is potentially useful and all bad writing potentially harmful. I think art that depicts women in their twenties as hot messes might contribute to dialogues about everything from mental and sexual health to career choice and motherhood. I think, though, that there is a fascination with the seamy and the broken in this society, and that stories about women in harmful circumstances are perhaps more common than is quite helpful. This fascination is a central aspect of my doctoral work, because there’s an old and very interesting aesthetic tradition to our desire to make degradation and suffering into art. We should, I think, look carefully at this desire, because I do believe that art has moral implications, and if we’re satisfied with only the messed-up twenty-something girls, without signs of their growth (See Nussbaum on “Girls” ) that just indicates that we, as a society, have a lot more growing up to do.

KC: With that “thrilling sense of newness” you document, you were on to something though, and it wasn’t all in your head. Reading your book, I was struck by how you’d documented a really pivotal time in the history of Toronto, a burgeoning sense of urbanism and civic awareness among a certain class/demographic of downtowners who were made to feel as though they had a say (or deserved one) in how the city was being shaped around them. (Edward Keenan documents the same thing through a less personal filter in his new book Some Great Idea: Good Neighbourhoods, Crazy Politics and the Invention of Toronto.) Did you have a sense as you wrote Here We Are Among the Living that you were writing a Toronto book? What role does the city play as a character in your story?

KC: With that “thrilling sense of newness” you document, you were on to something though, and it wasn’t all in your head. Reading your book, I was struck by how you’d documented a really pivotal time in the history of Toronto, a burgeoning sense of urbanism and civic awareness among a certain class/demographic of downtowners who were made to feel as though they had a say (or deserved one) in how the city was being shaped around them. (Edward Keenan documents the same thing through a less personal filter in his new book Some Great Idea: Good Neighbourhoods, Crazy Politics and the Invention of Toronto.) Did you have a sense as you wrote Here We Are Among the Living that you were writing a Toronto book? What role does the city play as a character in your story?

SB: I’m glad that my book brought something out for you about the changes that have been happening in Toronto. From the beginning I wanted to write about this city, which still, in the early years of the millennium, had a kind of stigma around it. It had never been and would never be as cool as Montreal. You couldn’t go hiking or skiing the way you could if you lived in Vancouver, and the weed was more expensive. The sense that Toronto was Hogtown with a sheen of Bay St. lawyers was why, in 2002 when Samba Elegua went marching alongside a spontaneous parade through the Financial District, it felt so incendiary. That youthful feeling of “nowness” that Heller describes—the acute, almost overwhelming awareness of the singular moment being experienced—was intensified by the newness of what we were doing.

As the decade progressed, we also developed a sense of being in a kind of precious time before gentrification entered full swing. I felt a tremendous poignancy about the east end. Ty’s loft on Eastern Ave. was across a waste lot from what is now the Distillery District. It was a ghost town when he moved in, one that we could traipse through and wonder what would become of the beautiful red bricks, the wood shutters and cobblestones. The Canary, on Cherry St., was still a functioning diner where we ate cheap breakfasts, discovering over those smokes-and-eggs that I was fetishising a certain aesthetic that was very indicative of where I came from and the kind of life I desired. So our twenties were largely about learning the city, and what kind of city we wanted—in part by assessing the gentrification rumbling toward Kensington and Leslieville. Knowing that the qualities for which we loved these places would threaten them later. There’s a petition going right now to keep Loblaws out of Kensington. I have nothing against Loblaws, but that would seriously alter the nature of the neighborhood. (On an amazingly happy note, I discovered last night that Casa Acoreana, the iconic coffee shop at the corner of Augusta and Baldwin, is not going to be gentrified out of business. The landlord was going to raise the rent, but the outcry from the neighborhood and in local newspapers was so impassioned that he rethought the increase, and the shop gets to stay. A rare and inspiring bit of beauty, that.)

Michael tried to convince me yesterday that the Starbucks on Logan has been there for ten years. Oh no it hasn’t, I said, and I’ll tell you why I know; when we used to walk to the Tango Palace [a coffee shop at Queen and Jones where we’d do our homework on the weekends] I’d say, there will be a Starbucks in this area within three years. And the year after you moved out [in 2006],

there was one.

I think the city in my story is a kind of muse. Certainly it made me want to write about it all the time. And it generates creativity and joy by bringing people together—Joe, for instance, comes to Toronto from England intending to go on to Vancouver, but changes his mind and stays because he likes it. A desire for the city to be a community inspires Streets Are For People!, the collective which creates Pedestrian Sundays in Kensington. And you’re right, that’s not just about dancing in the streets, or playing giant chess on the asphalt while eating empanadas; it’s about people being involved in the shape this city takes, and feeling like we have a responsibility and a right to advocate for things that will make life good here.

Street festivals like Taste of the Danforth, which has something like a million attendees now, engender a similar spirit, if perhaps in less direct ways. Even though there’s more of a consumerist bent to these bigger festivals, they still promote independent businesses and bring people together—and that’s good for the city as a whole. I love, too, that this discussion is coming to places outside the downtown core. I don’t know as much about this as I’d like to, but I’m really hopeful that street festivals, bike lanes and farmer’s markets aren’t just going to remain the purview of 416-ers.

Keenan’s book is definitely on my summer reading list. The changes in Toronto aren’t entirely great, but we’re getting a lot right and it’s nice that people are paying attention to what those things are, so we can keep ’em coming.

KC: Growing up in Toronto, did you have a sense of its literary landscape, which has been underlined by recent projects such as Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto book and Project Bookmark installations? What Toronto books contributed to your own literary landscape?

KC: Growing up in Toronto, did you have a sense of its literary landscape, which has been underlined by recent projects such as Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto book and Project Bookmark installations? What Toronto books contributed to your own literary landscape?

SB: Honestly, growing up in Toronto I felt like this city wasn’t on any literary map at all. In part, that’s probably because when I started seriously reading, in my late teens and early twenties, I was doing the young person thing of reading about everywhere else. So it was The Famished Road, by Ben Okri, and Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The Beats, of course. And trying to catch up on “the classics”—you know, The Great Gatsby, Dostoyevsky, Balzac…

So all through my early twenties, as I was thinking of writing this book, and scribbling notes for it, I was motivated in part by my love for a city that seemed undocumented. It was something we talked about, my friends, my mom and I—how no work of art had yet made Toronto “cool,” or even interesting. There was no romance about it at all. To some extent I still think that’s the case. Everyone I know was pretty darned excited when the movie Scott Pilgrim vs. The World came out, and we could recognize Bloor St., and there’s that scene where they’re CD shopping in Honest Ed’s.

It wasn’t until I was in the first year of my PhD, and TA’d for Modern Canadian Fiction, that I read a bunch of books set in Toronto: Hugh Garner’s Cabbagetown, which, despite now being unfashionable (its stodgy realism and blatant social agenda) I truly enjoyed. Austin Clarke’s excellent novel The Meeting Point was the first—and remains the only, come to think of it—depiction I’d read of Forest Hill. Barbara Gowdy’s labyrinthine Don Mills streets in Falling Angels were a revelation that Toronto’s suburbs had been made into art (which I hope to see a lot more of).

For me, best of all was Dionne Brand’s What We All Long For. That novel evokes the Toronto that I know and love: the youth of the four main characters capture the city’s restless, growing heart, its striving for beauty. The students loved that book, too. Our outstanding prof, Cheryl Cowdy, introduced us to the idea of psychogeography (now such a buzz word, thanks to Shawn Micallef’s 2011 book), and the concept just took off for students when we studied What We All Long For–I think because it was current, and the city so recognizable. The class got a lot of pleasure from looking at how characters were responding to their environments, and there are so many different Toronto environments depicted in Brand’s book that students were both learning about and identifying with; it made the fictional world very real to them, and I think made the city more real to them at the same time.

I’m excited that so much more art is being made in and about Toronto. I’d love to see more renderings of Toronto in the 1960s, or the 1980s, when I think a lot was changing. I’m working on a story set then; I’m hoping to include something about Operation Soap, the bathhouse raids on Richmond Street in 1981.

KC: So now I’m excited that you’re making more art in and about Toronto. Anything else exciting that you’re working on? And what are you reading right now?

SB: Well, there’s the short stories; the one that’s finished is a very long story called “The Optimists.” I’ve also got a lot of poems—many of which involve Toronto—that I’d like to turn into a book.

I’ve just started The Golden Bowl, by Henry James, who I love because he can make thinking the central action of a novel. I’m also reading a book called Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity by Richard Rorty, which I’m hoping is going to help me make a case for the social utility of liberal guilt and self