April 11, 2013

A Book for Baby's Library

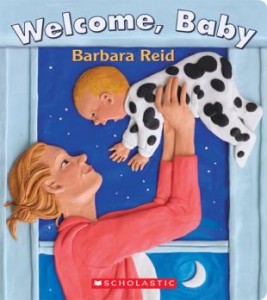

I bought a book for the new baby this week, the very first book of this baby’s own. It’s Welcome, Baby, a gorgeous new board book by Barbara Reid that I’m sort of thinking was written just for our new baby. If you know Barbara Reid’s illustrations, then you already know the book is beautiful–I’m in love with the quilt on the title page. “Welcome, baby, welcome!/ All the world is new,/ And all the world is waiting/ To be introduced to you…” the book begins, with a picture of a couple holding their new little one, a tree and robin just outside the window. And what I really love is that older siblings are a part of this welcome too, and so Harriet gets to point to the picture of Big Kid and Baby playing trucks, and saying, “That’s me!” of the former, and so too with the picture of the siblings splashing in the paddling pool. It ends, “We’ll hold you close,/ And let you fly.” which is just perfect, and the whole trick of being a parent really. I look forward to reading this one over and over, and in delighting as new tiny hands learn to grasp its pages.

I bought a book for the new baby this week, the very first book of this baby’s own. It’s Welcome, Baby, a gorgeous new board book by Barbara Reid that I’m sort of thinking was written just for our new baby. If you know Barbara Reid’s illustrations, then you already know the book is beautiful–I’m in love with the quilt on the title page. “Welcome, baby, welcome!/ All the world is new,/ And all the world is waiting/ To be introduced to you…” the book begins, with a picture of a couple holding their new little one, a tree and robin just outside the window. And what I really love is that older siblings are a part of this welcome too, and so Harriet gets to point to the picture of Big Kid and Baby playing trucks, and saying, “That’s me!” of the former, and so too with the picture of the siblings splashing in the paddling pool. It ends, “We’ll hold you close,/ And let you fly.” which is just perfect, and the whole trick of being a parent really. I look forward to reading this one over and over, and in delighting as new tiny hands learn to grasp its pages.

April 10, 2013

Glossolalia by Marita Dachsel

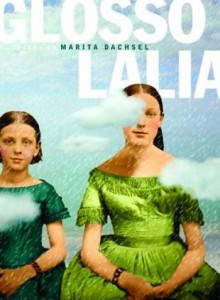

Marita Dachsel is a friend, and I was already inclined to like her new book Glossolalia because I’ve got a thing for obscure historical figures/stories whose voices are resurrected via poetry. In Glossolalia, the stories belong to the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormons, though Dachsel is careful to point out that her book is not meant to be a biography or a historical work. Rather, as Sharon McCartney explained with her Laura Ingalls Wilder poems, “the voices, the characters and the details are vehicles, a way to say what I want to say.”

Marita Dachsel is a friend, and I was already inclined to like her new book Glossolalia because I’ve got a thing for obscure historical figures/stories whose voices are resurrected via poetry. In Glossolalia, the stories belong to the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormons, though Dachsel is careful to point out that her book is not meant to be a biography or a historical work. Rather, as Sharon McCartney explained with her Laura Ingalls Wilder poems, “the voices, the characters and the details are vehicles, a way to say what I want to say.”

Glossolalia is a curious, wonderful book, in which a “self-avowed agnostic feminist uses mid-nineteenth century Mormon America as a microcosm for… universal emotions…”. Through Smith’s wives, each one with her own name, point of view and distinct voice, Dachsel explores ideas about love, marriage, pregnancy, motherhood, jealousy, domesticity, sex, trust, and betrayal. While the poems themselves are united by their representation of the voices of Smith’s wives, their styles and approaches are remarkably diverse, some written with formality and great distance, others more ribald and contemporary in tone. Apart from a few (often negative) examples, there is no sense of connection between these women, the poems showing their experiences of the world to be remarkably disparate, complicating tidy ideas of sisterhood. Dachsel’s wives are less a chorus than a cacophony, a crowd of dissonant voices, each shouting to be heard above the others.

But hear them, we do. The wives each emerge as distinct, aware, embodied, and it is the smallness and closeness of poetry (as well as their poet’s talent) that brings them so to life.

April 9, 2013

Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

I never got over Behind The Scenes at the Museum, Kate Atkinson’s first novel which won the Whitbread Award in 1995 (“‘A 44-

I never got over Behind The Scenes at the Museum, Kate Atkinson’s first novel which won the Whitbread Award in 1995 (“‘A 44-

I was ecstatic to learn, however, that her new novel would be a return to straightforward literary form. Well, not straightforward exactly, because Atkinson makes a point of taking form and exploding it into a million pieces. There is nothing at all straightforward about Kate Atkinson’s fiction, and what has always delighted me most about her literary novels is how covertly they’re all detective novels as much as Case Histories et. al. That there is ever such mystery at the core of her books–ghosts and dead bodies and things unexplained.

What is explained, however, what most readers will know because they start reading is that Life After Life comes with a gimmick. Think Sliding Doors and The Post-Birthday World, though not with parallel lives exactly but an array of them instead, strung together like a garland of paper chain dolls. Ursula Todd comes to life, then she dies, and then she’s born again and again, after each death returned to her beginnings, that night in 1910 when she comes into the world during a snowstorm. But then this isn’t even really the point, and here’s what allows Kate Atkinson to defy the bounds of genre: the point of this book isn’t the fantastic, but that it was written by Kate Atkinson and she’s wonderful.

I began this book with a strange sense of deja-vu (which was funny in itself because deja-vu is what it’s all about) because it reminded me so much of AS Byatt’s The Children’s Book, which I read four years ago when I was even more ridiculously pregnant than I am right now. The same depiction of the Edwardian middle-class family in a rural idyll (Todefright Hall vs. Fox Corner) with more children that it knows what to do with, some of whom are suspected to not really belong. And the banker father, fairy story references, connections to Germany. Both novels are setting out to do vastly different things, but in Atkinson’s I sensed an echo of the Byatt, and I loved that.

Ursula is born, Ursula dies, and then Ursula is born again, and while Atkinson does not explicitly spell out Ursula’s consciousness of her situation, her actions portray a dawning awareness that there is more to her life than just this one. This awareness manifests as strange sense of dread when she is young, that keeps her firmly on the beach where she’d drowned just a short lifetime ago. Her plight turns comical as she attempts numerous time to prevent her family’s maid from attending WW1 victory celebrations at which she’ll encounter the Spanish influenza and go on to infect Ursula and her beloved younger brother. Ursula eventually resorts to pushing her down a flight of stairs (thus saving the day), and ending up on a psychiastrist’s couch. Her parents are concerned with her oddness, her propensity for deja-vu.

Ursula comes up with clever ways of avoiding her previous mistakes, managing to make it through the 1920s and ’30s and only dying a handful of times. She falls in love, she has affairs, she stays single, she suffers a disastrous marriage, she is disgraced, she triumphs, she falters, and then is born again, determined to make her way. The connections and disconnections between Ursula and her siblings are particularly compelling. World War Two, however, proves to be an enormous impediment to Ursula’s lifeline. Again and again, she finds herself killed in the Blitz, and when she finally manages to skirt her particular explosion, other complications present themselves. Her fate seems determined to find her no matter how she goes out of her way to avoid it.

There is texture to a book like this, and the pleasure of seeing secondary characters from a wide variety of angles–Ursula’s mother in particular whose role in the novel’s conclusion was ingenious. Life After Life is a long book, as befitting a life lived over and over again, and I savoured its slowness, the returns to where I’d been before, places and people I was happy to revisit. I appreciated the specificity of its detail, the brilliance of its writing, its genre-blurring, its daringness in reframing the shape of a narrative, and yes, this is Kate Atkinson, so there is going to be that too.

April 9, 2013

Books For Sale!

On Saturday morning, Harriet’s playschool (Huron Playschool Cooperative) will hold their annual Book/Toy/Bake Sale to raise funds for the Jenna Morrison Family Trust. This event nicely coincides with my need to rid my house of much of its contents, and so I will be donating a huge pile of adult books to the sale, and some of them are really good.

On Saturday morning, Harriet’s playschool (Huron Playschool Cooperative) will hold their annual Book/Toy/Bake Sale to raise funds for the Jenna Morrison Family Trust. This event nicely coincides with my need to rid my house of much of its contents, and so I will be donating a huge pile of adult books to the sale, and some of them are really good.

Good books at good prices for a good cause–what could be better? Come out on Saturday April 13 from 10:00-12:30, 383 Huron St.

April 7, 2013

New kids' books we've been enjoying lately

Mister Dash and the Cupcake Calamity by Monica Kulling and Esperanca Melo: Before reading this book, we’d thought about its title and speculated as to what the calamity might be, and we were wrong wrong wrong. We hadn’t yet read the first Mister Dash book, so we had no idea that Mister Dash himself would be the picture of calmness and civility while the calamity was everything that happened around him. When Madame Croissant decides to start up a cupcake company, she enlists her faithful hound to help (and makes him wear a baker’s hat, much to his dismay). When the tornado that is Madame Croissant’s granddaughter Daphne enters the mix, there has to be cupcake batter scraped off the ceiling and other calamities averted. In every situation, Mister Dash narrowly saves the day, and all are overjoyed in the end to find the cupcake business is a go-go! Especially since Mister Dash is finally allowed to take his silly hat off.

Mister Dash and the Cupcake Calamity by Monica Kulling and Esperanca Melo: Before reading this book, we’d thought about its title and speculated as to what the calamity might be, and we were wrong wrong wrong. We hadn’t yet read the first Mister Dash book, so we had no idea that Mister Dash himself would be the picture of calmness and civility while the calamity was everything that happened around him. When Madame Croissant decides to start up a cupcake company, she enlists her faithful hound to help (and makes him wear a baker’s hat, much to his dismay). When the tornado that is Madame Croissant’s granddaughter Daphne enters the mix, there has to be cupcake batter scraped off the ceiling and other calamities averted. In every situation, Mister Dash narrowly saves the day, and all are overjoyed in the end to find the cupcake business is a go-go! Especially since Mister Dash is finally allowed to take his silly hat off.

Oy. Feh. So? by Cary Fagan and Gary Clement: I don’t think I’m the target audience for this book, as no one in my family has ever used a lot of Yiddish, but I do know about great aunts and uncles, the kind who would visit on Sundays in enormous automobiles. These relatives at a remove who plant themselves on the couch and aren’t so interested in the children. In Oy. Feh. So?, Aunt Essy, Aunt Chanah and Uncle Sam aren’t interested in anything, all attempts at conversation resulting in their respective signature exclamations, and so one Sunday the kids decide they aren’t going to take it and go to extremes to rattle their unshakably miserable rellies. It’s a funny story that appeals to a similar nostalgia as Barbara Reid’s The Party, the humour underlined by Clement’s cartoon illustrations.

Oy. Feh. So? by Cary Fagan and Gary Clement: I don’t think I’m the target audience for this book, as no one in my family has ever used a lot of Yiddish, but I do know about great aunts and uncles, the kind who would visit on Sundays in enormous automobiles. These relatives at a remove who plant themselves on the couch and aren’t so interested in the children. In Oy. Feh. So?, Aunt Essy, Aunt Chanah and Uncle Sam aren’t interested in anything, all attempts at conversation resulting in their respective signature exclamations, and so one Sunday the kids decide they aren’t going to take it and go to extremes to rattle their unshakably miserable rellies. It’s a funny story that appeals to a similar nostalgia as Barbara Reid’s The Party, the humour underlined by Clement’s cartoon illustrations.

Hoogie in the Middle by Stephanie McLellan and Dean Griffiths: This was one book that did not immediately appeal to my adult kid-lit-loving sensibilities, but I knew something was up when Harriet suddenly couldn’t stop talking about it. (“You be Pumpkin, you be Tweezle, and I’ll be Hoogie,” she’d demand of whoever was in her company, or a variation on this.) I asked her why she liked the book so much: “Because Hoogie’s a monster and she’s nice,” Harriet answered, and I liked that answer. In her family of Muppet-like creatures, Hoogie is not the biggest or the smallest, but she’s stuck in the middle instead–ever too big or too little. Until one day her frustration gets too much and Hoogie explodes, and then her parents take the time and let her know how much they love their monster in the middle (“You’re the sun in the middle of the solar system,” says Dad, as they swing her through the air. “The pearl in the middle of the oyster,” says Mom as they catch her in their arms.”) This is a good teaching book for any middle child, but also (I have a feeling!) useful for any little one suffering a bit of family displacement. Hoogie will help them to articulate their feelings and know they aren’t alone.

Hoogie in the Middle by Stephanie McLellan and Dean Griffiths: This was one book that did not immediately appeal to my adult kid-lit-loving sensibilities, but I knew something was up when Harriet suddenly couldn’t stop talking about it. (“You be Pumpkin, you be Tweezle, and I’ll be Hoogie,” she’d demand of whoever was in her company, or a variation on this.) I asked her why she liked the book so much: “Because Hoogie’s a monster and she’s nice,” Harriet answered, and I liked that answer. In her family of Muppet-like creatures, Hoogie is not the biggest or the smallest, but she’s stuck in the middle instead–ever too big or too little. Until one day her frustration gets too much and Hoogie explodes, and then her parents take the time and let her know how much they love their monster in the middle (“You’re the sun in the middle of the solar system,” says Dad, as they swing her through the air. “The pearl in the middle of the oyster,” says Mom as they catch her in their arms.”) This is a good teaching book for any middle child, but also (I have a feeling!) useful for any little one suffering a bit of family displacement. Hoogie will help them to articulate their feelings and know they aren’t alone.

What a Party! by Ana Maria Machado and Helene Moreau: This is a bit like those If You Give a Mouse a Cookie books, but so much more interesting, and involving birthday parties, which is a pretty important topic if you happen to be four years old. The book posits what might happen if your mom, in a moment of distraction, tells you to invite “anyone you’d like” to your upcoming party, and then you invite everyone you know, who happens to also resemble the United Nations, and each friend brings a party food from their own particular culture and pets (which are another topic of fascination if you’re four). The party becomes a glorious celebration of delicious food, live music, salsa dancers and a raggae band, and then it goes all night long (which could happen “especially if the parents drop in and start having drinks and chatting instead of going home”). What a Party! is the perfect recipe for the “craziest, wildest, funnest party ever”, Moreau’s illustrations capturing the festive mood perfectly.

What a Party! by Ana Maria Machado and Helene Moreau: This is a bit like those If You Give a Mouse a Cookie books, but so much more interesting, and involving birthday parties, which is a pretty important topic if you happen to be four years old. The book posits what might happen if your mom, in a moment of distraction, tells you to invite “anyone you’d like” to your upcoming party, and then you invite everyone you know, who happens to also resemble the United Nations, and each friend brings a party food from their own particular culture and pets (which are another topic of fascination if you’re four). The party becomes a glorious celebration of delicious food, live music, salsa dancers and a raggae band, and then it goes all night long (which could happen “especially if the parents drop in and start having drinks and chatting instead of going home”). What a Party! is the perfect recipe for the “craziest, wildest, funnest party ever”, Moreau’s illustrations capturing the festive mood perfectly.

April 3, 2013

The Sally Draper Poems

While I never finished reading The Collected Stories of John Cheever, which has been sitting on the table before me now for more than 2 years, my literary obsession with Mad Men continues, as does my obsession with Mad Men in general. (We have spent the last while rewatching the entire series, and are now partway through Season 4. We will save Season 6 until our baby sleeps for at least an hour at a time. Basically, I do not care to acknowledge that there are any other televisions shows in the world.)

While I never finished reading The Collected Stories of John Cheever, which has been sitting on the table before me now for more than 2 years, my literary obsession with Mad Men continues, as does my obsession with Mad Men in general. (We have spent the last while rewatching the entire series, and are now partway through Season 4. We will save Season 6 until our baby sleeps for at least an hour at a time. Basically, I do not care to acknowledge that there are any other televisions shows in the world.)

So I was overjoyed to read “The Sally Draper Poems”, written by one of my favourite poets Jennica Harper. These poems are so very good, demonstrating Harper’s sharp wit, gift for voice, and her amazing sympathy with a young girl’s perspective. I love the texture that they add to the Mad Men universe.

See also:

- My post, What Sally Draper Must Have Been Reading

- The poem “Don Draper” by Nyla Matuk, who has just been nominated for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award

April 2, 2013

Bone and Bread by Saleema Nawaz

In a way, it seems fitting to talk about a recipe in reference to Saleema Nawaz’s first novel Bone and Bread, a book that is so very much about food and hunger. It seems fitting to say that this is a novel absolutely packed/plotted with ingredients: family drama, tragedy, humour, intrigue, politics. Truly, there is something here to appeal to every reader (spectacular writing not the least of it), but really this wouldn’t be the right way to talk about the book at all, to reduce it to its parts. Because the thing about Bone and Bread is its very wholeness, the effortlessness nature of its construction. “It’s so good, and it’s not even trying,” was what I said to someone when I heard Saleema Nawaz read at Type Books two weeks back. I’d started reading it the evening before, burning through 100 pages before I turned my light out.

In a way, it seems fitting to talk about a recipe in reference to Saleema Nawaz’s first novel Bone and Bread, a book that is so very much about food and hunger. It seems fitting to say that this is a novel absolutely packed/plotted with ingredients: family drama, tragedy, humour, intrigue, politics. Truly, there is something here to appeal to every reader (spectacular writing not the least of it), but really this wouldn’t be the right way to talk about the book at all, to reduce it to its parts. Because the thing about Bone and Bread is its very wholeness, the effortlessness nature of its construction. “It’s so good, and it’s not even trying,” was what I said to someone when I heard Saleema Nawaz read at Type Books two weeks back. I’d started reading it the evening before, burning through 100 pages before I turned my light out.

I probably shouldn’t have been so blown away by the novel’s goodness though. That night at Type Books was the first time I met Saleema Nawaz in person, but I’ve known her online for a while, and I’ve known her best through her writing, through the essay she’s contributed to my forthcoming anthology. And from her essay, I knew already that Nawaz is the real thing, a writer as devoted to language as she is to story. The kind of writer who crafts lines like, “The truth was that I liked all [the bagel boys]. I wanted all of them in the way that a dissonant chord wants resolution, setting a vibration out into the world. In the way that a teenager wants to get her life started.”

“My sister and I stopped bleeding at the same time,” an early chapter begins. Told from the perspective of Beena who has always been strangely bound to her sister Sadhana, mainly through the eccentric nature of their upbringing, this line is emblematic of the ways in which the sisters’ experience are linked but ever worlds apart. Because Beena has stopped her period because she is pregnant, just sixteen years old after not even a real romance with one of the boys who works in her uncle’s bagel shop. While Sadhana’s anorexia has begun to overtake her body and mind, a disease whose symptoms would come and go, but would eventually claim her life 18 years later.

Perhaps it’s just because I am pregnant myself, but I don’t know how I could have made it through this book without the wood fire bagel place that has recently opened in close range of my house. Nawaz writes so evocatively about food and hunger, the novel’s most central metaphors, but she renders them literally as well, so much so that it made my stomach growl. Beena and Sadhana are raised in the apartment above the bagel shop in Montreal, the shop that had been their father’s until his sudden death. They’d lived in the apartment with their mother until her death (at the dinner table, yes) during their early teen years, after which their severe and distant uncle became reluctantly enlisted with their care. It’s soon after this that they both stop bleeding, each girl’s life taking on a remarkably separate trajectory even as their experiences remain inextricably linked.

These events are narrated by Beena in the present day who is still in shock from her sister’s death six months before, and who suffers its fall-out as her eighteen year-old son Quinn clearly blames her for what happened to his beloved aunt. But what did happen to Sadhana? Beena is not entirely sure. She suspects her son knows more about it than he’s letting on, and that there is a connection between Sadhana and the probing questions Quinn has started asking about the father he never knew. The web becomes more complicated as Beena uncovers a link between Sadhana’s political work advocating for a refugee and Quinn’s father who has become a right-wing anti-immigrant politican in Quebec and whose name is turning up everywhere. Beena must face her own questions about the cirumstances of her sister’s death and the possibility of her own complicity in its circumstances.

This is a fascinating novel about sisterhood, and what is most compelling about it, in spite what this novel’s gorgeous cover design might suggest, is that there is no symmetry between Beena and Sadhana. They’re not twins, though there is something twin-like in the bond between them, but this is mainly in that, as the text points out at one point, it’s difficult to tell where one sister ends and the other begins. They are complicated, messy personalities who are compatible in some respects, but drive each other apart in others. Their love is as intense as their rivalry and the conflict ever firing between them. Sadhana’s true nature is obscured by Beena’s perspective, as there was so much she never knew about her sister, and so she remains an enigma haunting the novel. But Beena too is just as hard to read, and in many ways she’s as unknown to herself as she is to her reader, and unpuzzling both these women who refuse to be pinned down (or earn our outright sympathy) is one of the book’s most fascinating pleasures.

Bone and Bread is an intense read, 400 pages but a fast read, gorgeously literary and a page-turner. And I’m not really sure what possible recipe could ever come up with such a mix, but as a reader I am overjoyed that Saleema Nawaz worked it out so well.

April 1, 2013

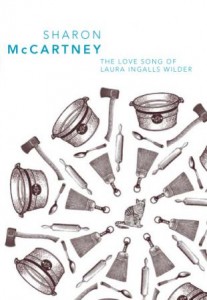

The Love Song of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Sharon McCartney

Marita Dachsel recommended The Love Song of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Sharon McCartney right when our family was in the middle of reading On the Banks of Plum Creek, and so it seemed like an irresistible pick. Because we’ve been so fascinated by the gaps and silences in the Little House books, by what goes on between the lines. What is it to be Caroline Ingalls, we’ve been wondering for a while, and are there varying tones to her declarations of, “Oh, Charles.”? What does “Oh, Charles.” really mean?

Marita Dachsel recommended The Love Song of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Sharon McCartney right when our family was in the middle of reading On the Banks of Plum Creek, and so it seemed like an irresistible pick. Because we’ve been so fascinated by the gaps and silences in the Little House books, by what goes on between the lines. What is it to be Caroline Ingalls, we’ve been wondering for a while, and are there varying tones to her declarations of, “Oh, Charles.”? What does “Oh, Charles.” really mean?

In her foreward, Sharon McCartney writes of her poems, “I don’t think of them as being an extension of Wilder’s stories. Rather, the voices, the characters, and the details are vehicles, a way to say what I want to say.” But saying what she wants to say via these characters, voices, details renders these poems familiar territory for me, which is important when poetry itself is decidedly not.

From “Ma”: “This morning I addressed the roof beams, /Charles twitching in sleep beside me: /Today I will do whatever I want.” I was amazed by the perspective of a bull-dog in, “Jack, Swept Away When the River Rises Suddenly Mid-Ford” and of the tattered rag-doll in “Charlotte”. Some poems I suppose I read as voyeuristic glimpses deeper inside the book, such as “Nellie Olesen” which imagines Laura’s nemesis years later, sitting mildly at a temperance meeting. “Pa’s Penis” was not as naughty as we’d imagined.

The Love Song of Laura Ingalls Wilder has much in common with Lorna Crozier’s recent collection The Book of Marvels, itself a catalogue of the hidden lives of ordinary things. As interesting as “Pa’s Penis” and the revelation that the Ingalls family had a son who died at nine months of age is the poem from the perspective of the butter churn, the chinook, a rocking chair, the boughten broom. As interesting as the Little House allusions are the poems themselves, and how they turn familiar territory into a vision that’s altogether new.

April 1, 2013

On being that innocent again.

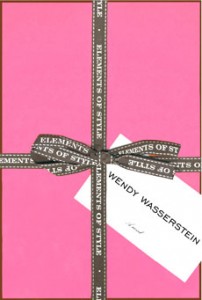

I took myself out for lunch on Saturday, with Wendy Wasserstein’s The Elements of Style for company. I haven’t eaten alone in a restaurant for a long time (and in fact, I rarely get to eat in restaurants without the company of someone who is ever in danger of knocking over her water glass and ever requires ketchup and grubby crayons as a garnish), but learning the pleasures of doing so was once upon a time one of the greatest lessons in my education of being a grown-up woman. So when the prospect of a free Saturday afternoon presented itself to me, a solo lunch date was at the top of my agenda. A brand new baby is scheduled to explode into my life in about 8 weeks, and who knows when I’ll ever get to be alone again?

I took myself out for lunch on Saturday, with Wendy Wasserstein’s The Elements of Style for company. I haven’t eaten alone in a restaurant for a long time (and in fact, I rarely get to eat in restaurants without the company of someone who is ever in danger of knocking over her water glass and ever requires ketchup and grubby crayons as a garnish), but learning the pleasures of doing so was once upon a time one of the greatest lessons in my education of being a grown-up woman. So when the prospect of a free Saturday afternoon presented itself to me, a solo lunch date was at the top of my agenda. A brand new baby is scheduled to explode into my life in about 8 weeks, and who knows when I’ll ever get to be alone again?

I did enjoy this blog post by a writer who is about to give birth to her second child and contemplating the distance she’s travelled since she was waiting to birth her first. She writes about the loss of self that transpires when a woman becomes a mother, and looks forward to this new birth because it will occur without that loss. I feel similarly. Harriet made me a mother, which was a difficult, nearly traumatic, absolutely not natural for me experience. When she was born, I did not know how to love a child as a mother does, and I had to grow into that love. I tell her all the time how I did not know how to be a mother before her, and how she taught me, and how excited I am to meet her sibling because I know how to do it now. The love I have for our new baby already comes via my love for Harriet, as though Harriet is the connection between us. Harriet, of course, sees nothing unusual about being a linchpin. She is quite sure that she is the centre of the universe after all.

I did enjoy this blog post by a writer who is about to give birth to her second child and contemplating the distance she’s travelled since she was waiting to birth her first. She writes about the loss of self that transpires when a woman becomes a mother, and looks forward to this new birth because it will occur without that loss. I feel similarly. Harriet made me a mother, which was a difficult, nearly traumatic, absolutely not natural for me experience. When she was born, I did not know how to love a child as a mother does, and I had to grow into that love. I tell her all the time how I did not know how to be a mother before her, and how she taught me, and how excited I am to meet her sibling because I know how to do it now. The love I have for our new baby already comes via my love for Harriet, as though Harriet is the connection between us. Harriet, of course, sees nothing unusual about being a linchpin. She is quite sure that she is the centre of the universe after all.

There is something different about going over the edge of a cliff when you’ve been over the cliff before. I spent my entire pregnancy with Harriet in a state of disbelief, really, not remotely convinced that there would be a baby at the end of it. There had never been a baby more unfathomable than Harriet, I supposed, so even my birth preparations were half-hearted, and I never allowed myself to imagine beyond it. This time, however, I’m going over the cliff and recognizing all the landmarks. I know even that the cliff itself is not the point, and that the journey beyond goes on and on. I have a concrete awareness of my own limits as well, which were pretty much the greatest lessons I took away from new motherhood, and I’m not going to deny them. This is why my husband will be spending the summer at home with us as we settle into life as a family of four. This is why we’ve bought a queen-sized bed. This is why I will unabashedly read through breastfeeding marathons instead of staring into my baby’s goopy eyes. This is why I’m going to hate having a baby sometimes and I’m not going to beat myself up about that. I will not enjoy every minute. This is why I’m not going to push myself to recreate ordinary life right away as the dust settles from our new baby’s arrival. This time, I know that ordinary life will come back without me even trying. That the trying is the hardest part, and I just have to be patient instead. I just have to get a little bit better at being patient.

There is something different about going over the edge of a cliff when you’ve been over the cliff before. I spent my entire pregnancy with Harriet in a state of disbelief, really, not remotely convinced that there would be a baby at the end of it. There had never been a baby more unfathomable than Harriet, I supposed, so even my birth preparations were half-hearted, and I never allowed myself to imagine beyond it. This time, however, I’m going over the cliff and recognizing all the landmarks. I know even that the cliff itself is not the point, and that the journey beyond goes on and on. I have a concrete awareness of my own limits as well, which were pretty much the greatest lessons I took away from new motherhood, and I’m not going to deny them. This is why my husband will be spending the summer at home with us as we settle into life as a family of four. This is why we’ve bought a queen-sized bed. This is why I will unabashedly read through breastfeeding marathons instead of staring into my baby’s goopy eyes. This is why I’m going to hate having a baby sometimes and I’m not going to beat myself up about that. I will not enjoy every minute. This is why I’m not going to push myself to recreate ordinary life right away as the dust settles from our new baby’s arrival. This time, I know that ordinary life will come back without me even trying. That the trying is the hardest part, and I just have to be patient instead. I just have to get a little bit better at being patient.

I also have to avoid the inclination to try to get it right this time. There really is no getting it right. This is not a do-over. New motherhood is a mad fumble, no matter what you do, and one way or another, I’m going to end up crying on the floor without clothes on. But I will not be surprised when it happens this time, and that is really something.

I never thought I could be this open-eyed excited about having another child. When Harriet was small, I looked back at the end of my pregnancy with the saddest nostalgia. “We’ll never be that innocent again,” I remember thinking after bringing our small baby over to visit friends whose own baby’s birth was imminent. But somehow, we’ve unlearned reality and I’m excited again. Maybe I’ve become wise enough to know we’ll get through the hard times, that they’re worth it. Or maybe I’m a fool and the return to innocence is just a survival mechanism.

A bit of both, perhaps. I guess we’ll have to see what I have to say about it all once I’m back there crying on the floor.