April 29, 2013

On Passing Judgement

My favourite response to my “Stick Rage” post at Bunch Family was the person who wrote, “Save it for your personal blog, Kerry Clare. Clearly, you’re about judgement and singling people out, not bringing families together.” I laughed. “Clearly, you’re about judgement…” Man, I thought, you don’t even know. Because I am all about judgement. Really. This is why some people find me amusing to converse with, and I don’t know that I’m so singular in this characteristic because the people I like to converse with are pretty “judgy” as well. In the best way, of course, by which I mean that they are funny, don’t suffer fools gladly, have ideas and opinions and no qualms about expressing them.

This may be why I’ll never make it as a parenting blogger. “The world is so judgemental already. Let’s stop judging. Everyone is entitled to their opinion and actions.” This was a comment on a recent post at the blog Playground Confidential, and when I read it, I thought (and judged), “How positively uninteresting it must be to go about the world with that perspective.” I am troubled by this idea that women in particular must amass whilst cooing soft noises of mutual support and approval, because who actually does this? (Speaking of parenting blogs, I am also troubled by the sheer number of people who pass their lives by littering the the internet with sponsored blog posts about how much their domestic lives are assisted by Hamburger Helper, but that’s a judgement for another day.) Sure, everyone is indeed entitled to their opinions and actions (but no! even this isn’t true!) but therefore aren’t I perfectly entitled to find you an asshole, or an idiot? I’m even entitled to say as much. And you’re more than welcome to judge right back, but please don’t do so on the basis of me being judgemental because it’s an awfully terribly tiresome feedback loop and I don’t even care.

What bothers me the most about this whole “Let’s stop judging” approach is its dishonesty. It is a rare person who ever really pulls this off, and the rest of us are just whispering judgements to our friends behind your back. I’m not sure this is necessarily kinder than making pronouncements aloud. Now of course, to judge and to be vicious are not necessarily the same thing and the distinction between the two is important. But it’s a eye of the beholder thing, really, and haven’t we talked about this in terms of book reviewing a hundred thousand times? I’ve tried to work around this as a book reviewer by not reading or reviewing books I know I’m programmed to respond to with judgement instead of an open mind. It’s not worth my time, and neither the world’s to pollute it with my vitriol (this post and the one about stick families, of course, excluded. And can you tell that I am nine months pregnant? I have never been such a judger-naut! Or used so many italics!).

So this is the reason that I haven’t read Drunk Mom by Jowita Bydlowska, though certainly it’s a book I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about. As someone who has made a thing of writing honestly about motherhood and expressing the truth of my own difficult experiences with its early days, certainly I’m intrigued by Bydlowska’s project and by my own ambivalent response to it. And I was also intrigued by Sarah Hampson’s interview with Bydlowska, which dared to pose difficult questions and not just those that had been approved by Bydlowsk’s publicist. The interview was interesting, which is more than you can say about the interviews with her that have appeared elsewhere with their polite questions and predictable answers. I’m not even sure that it was journalistically troubling, because good interviewers are always very much a character in the story they’re telling. The problem, I suppose, would be if Hampson had been dishonest with Bydlowska in their conversation, had hoodwinked her somehow, but it shouldn’t be a problem that Hampson was honest in how she responded to the book. This book for which Bydlowska’s own honesty and bravery have been so celebrated; why is another writer meant to just shut up and be polite?

I similarly appreciated Lisan Jutras’ review of the book in The Globe on Saturday. I didn’t find the review to be judgemental, but found instead that Jutras approached the book (as well as her response to it) with questions instead of conclusions (and herein is the distinction between a critical review and a cruel one, I think), that she broadened the conversation, which is precisely what a book review is meant to do. (More italics. I can’t stop). She questions this reflexive response of terming female memoirists as “brave”, she questions her own fascination with Bydlowska’s story and her discomfort with this.

“I’m torn about this book,” is something that somebody wrote to me the other day, and I’m having trouble discerning how any reader could not be. It is a troubling, fascinating book that is worthwhile for the questions it raises, I think, and I find it odd that we would judge anybody for asking them. To ask those questions is not to be lacking in compassion, but it’s to be curious about a book, about the world. (I also think the whole, “But the reviewer doesn’t even mention the prose style” is a little disingenuous. Drunk Mom is not about its prose, or at least its marketers don’t think it is, so I think we can be forgiven for not playing along with that game. Very few of us stare at car accidents for aesthetic reasons. I also recognize that this book is meant to be intended to help and support those suffering from addiction, but then what are we meant to do with it, those of us who aren’t undergoing such struggles? Other than not read it. A book has to exist on its own terms and be more than a life preserver.)

Bydlowska is in no way unique for being a woman who has been publicly rebuked for her mothering skills. Just yesterday, I read the fantastic essay “The Meaning of White” by Emily Urquhart about her experience as a mother whose child was born with albinism, and I was aghast by the rage expressed in the comments: apparently Urquhart is hijacking her daughter’s story, is ableist, is making something out of nothing, is a white supremacist. There is something troubling about this mass jumping on the hate-train that almost makes me want to rethink my so-called judgy life, but then I’ve gone and judged already–we already know that internet commenters are morons anyway and are really none of anyone’s concern, not mine, nor Emily Urquhart’s, or Jowita Bydlowska’s either.

My point is that when you tell your story, people are allowed not to like it. And when that story is you, judgement is going to come into play when people don’t like it, even if you do something shrewd like decide your book is an “autobiographical novel”. “The main character in this book is a such a kind of person and what is the author’s intention in representing herself this way” is a legitimate line of thinking to pursue for a reader/critic, [albeit not a great basis for critical assessment] but we’re all avoiding that conversation for fear of being impolite. We’re avoiding so many conversations for the sake of politeness, actually, and I’m not sure our books are any better for it. I’d far rather read an honest review that posed provocative questions than one that sang the praises of bravery as a singular reason for any book to be.

April 28, 2013

The Best Place on Earth by Ayelet Tsabari

Can this writer ever write, was my response when I read Ayelet Tsabari’s guest posts at The Afterword last month. And so I sought out her book The Best Place on Earth, a collection of stories about Israelis of Middle Eastern and African descent, only to discover that this wasn’t exactly what the book was “about” at all. Instead the centre of the book is Israel itself.

Can this writer ever write, was my response when I read Ayelet Tsabari’s guest posts at The Afterword last month. And so I sought out her book The Best Place on Earth, a collection of stories about Israelis of Middle Eastern and African descent, only to discover that this wasn’t exactly what the book was “about” at all. Instead the centre of the book is Israel itself.

After she hung up, she turned back to the news online. Ten injured, nobody dead. For a moment, she could see how her country might look to a Canadian. How Jerusalem could be perceived as the worst place to live, raise a family, a dangerous, troubled city, torn between faiths, a hotbed for fanatics and fundamentalists.

In her book, Tsabari provides a whole different impression. That Israel is more than just Jerusalem, first of all, and that its people live in towns, villages, and neighbourhoods with their own distinctions. And that the people themselves come from diverse backgrounds beyond even Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, that Israelis themselves aren’t homogeneous, and their nation is populated by immigrants legal and otherwise striving to better lives for themselves. That Jerusalem and Tel Aviv are cities where people live out their lives in rich detail, where the backdrop is vivid and vibrant, and ordinary life possesses many more dimensions than can be made out on a one minute news clip about the aftermath of an explosion. And even when characters have left Israel behind, its complexities are always tied up in impossible notions of home.

“Lovers in a Dangerous Time” was the song I had running through my head as I read these stories, particularly the line, “One minute you’re waiting for the sky to fall. Next you’re dazzled by the beauty of it all.” In “Tikkun”, a man encounters an old flame and is surprised to find she’s become an Orthodox Jew, that she’s somebody’s respectable wife now. They spend time together at a cafe that is destroyed in a bombing shortly after their departure, imploding for a moment any distance between them. In “The Poets in the Kitchen Window”, a young boy longs for certainty as Iraqi missiles fall near his neighbourhood and his mother lies ill in the hospital, but he finds solace in poetry instead. “Casualties” is a fantastic story about a young woman serving in the army whose personal life and professional life become unravelled as she drowns her troubles in sex and drink.

A Filipino woman working illegally as a caregiver tries to dodge authorities as she contemplates falling in love. A man brings his Canadian girlfriend to meet his long-estranged father near the Dead Sea and discovers that the parameters of their relationship have shifted. A woman arrives in Canada to meet her new grandchild and is presented with the fact that her daughter has decided not to have her son circumcised. In the collection’s title story, an Israeli woman fleeing her marriage arrives in Vancouver to measure herself against her sister’s very different choices and very different life, but the distance between them may not be as wide as it seems.

Tsabari is excellent at atmosphere and representing a very real sense of place. The great writing I noticed in her non-fiction comes through here as well–my favourite passage was a fabulously rendered awkward sex scene in which a girl’s older, more experienced lover attempts cunnilingus as she is seriously preoccupied with other things (“Stop thinking.”). Perhaps it’s my sensibility, but I appreciated the stories about older characters the most, felt that these characters were represented with more depth and complexity, and that these were the stories that pushed the limits of their form, were not just well-rendered realism but were also about story itself.

April 25, 2013

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.”–George Eliot, Middlemarch

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.”–George Eliot, Middlemarch

“And didn’t it always go like that–body parts not quite lining up the way you wanted them to, all of it a little bit off, as if the world itself were an animated sequence of longing and envy and self-hatred and grandiosity and failure and success, a strange and endless cartoon loop that you couldn’t stop watching, because, despite all you knew by now, it was still so interesting.” –Meg Wolitzer, The Interestings

Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings is so absolutely full of stuff, of the world, loud with that roar which lies on the other side of silence. Within the novel, we find echoes of its literary contemporaries–recent books like The Marriage Plot and Arcadia–and also more distant 19th century relations. And also the kind of stuff that fills up newspapers and magazines, cover-story “issues” like autism, gifted children, grief, depression, marriage, divorce, rape, third-world child labour, unemployment, and motherhood. So that on one hand, I can tell you that this is the story of a group of friends who meet at summer camp and whose ties grow and change during the decades that follow. But it’s also about the history of the last thirty years in New York and America. It’s about what it means to live history, and how characters change with their times. It’s about the democratic and egalitarian nature of youth, when friends could be duped into believing that they all have the same potential, that there is such thing as a level playing field, that it all comes down to talent and drive. Before it’s discovered that talent is mere, that being extraordinary is rare, and that factors such as money, connections, pedigree, physical and mental health, love, children, and luck come to define the path that a lifetime takes, and that those paths can lead in surprising directions.

At the centre of the story is Jules Jacobson, attending camp at Spirit of the Woods on a scholarship, perplexed and thrilled to find herself part of a circle of individuals who define themselves as “interesting”. She’s an outsider among them, yet she’s curiously accepted, which changes the way she sees herself. When the summer ends and she returns home to her family in suburbia, suddenly everything is mere, and the future (and the city) beckons in a way it never had before. She becomes part of the orbit of Ash and Goodman Wolf, brother and sister with inordinate privilege, is embraced into their family with the other “Interestings”: Jonah Bay, son a famous folksinger who squanders his own musical talent; Cathy, the dancer whose body has other plans for her; and Ethan Figman, whose talent for animation will catapult him to superstardom. The story moves through these different characters’ perspectives, and yet Jules remains its focus and we find her years later receiving Ash and Ethan’s annual Christmas newsletter (they eventually become a couple) with its extraordinary reports of their happenings, and being torn between love and hatred for her friends, contentment with her own more quotidian life and pure envy.

The structure of The Interestings is fascinating, the novel weaving back and forth through time without great shifts, effortless for the reader to follow and seemingly effortless for the writer too, though I can’t imagine that this was really the case. And yes, it is so interesting, a book so terrific to be absorbed in and whose end (at page 468) arrives too soon.

April 24, 2013

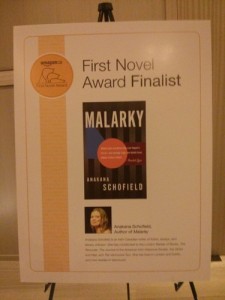

Malarky Triumphs!

Oooh, what a night! I’ve been a devotee of Anakana Schofield’s Malarky since I first read it just over a year ago now, and so it was fantastic to be in the crowd tonight as Our Woman, the book and its author finally got the credit they’ve long-deserved. So pleased that Malarky was tonight awarded the 2013 Amazon First Novel Award. Sometimes it all works out all right. And sometimes you also end up with the most mind-blowing assortment of desserts in your lap, on a plate even, ready to eat. They were as good as they looked.

Oooh, what a night! I’ve been a devotee of Anakana Schofield’s Malarky since I first read it just over a year ago now, and so it was fantastic to be in the crowd tonight as Our Woman, the book and its author finally got the credit they’ve long-deserved. So pleased that Malarky was tonight awarded the 2013 Amazon First Novel Award. Sometimes it all works out all right. And sometimes you also end up with the most mind-blowing assortment of desserts in your lap, on a plate even, ready to eat. They were as good as they looked.

April 23, 2013

Getting Ready

It is with as much relief as terror that we acknowledge that this is really happening. That after 36 weeks of us definitely thinking of getting around to performing these tasks that there is now a crib set up in our room, tiny diapers stacked next to the changing-pad, order created from the chaotic mess of our garret/closet which contains a ridiculous four-years-worth of baby and kid stuff. The baby clothes are laundered and waiting in a drawer. And the baby itself is head-down as confirmed by last week’s ultrasound and therefore I’ve not had to spend this week consulting moxibustionists. This is not to say that there aren’t a thousand things I want to/have to do before our baby arrives, but at least they don’t involve putting furniture together, matching tiny socks, or turning impossible babies. In a fundamental way, we are actually ready for the baby to come. And due to a crazy trick of nature, we’re even excited.

It is with as much relief as terror that we acknowledge that this is really happening. That after 36 weeks of us definitely thinking of getting around to performing these tasks that there is now a crib set up in our room, tiny diapers stacked next to the changing-pad, order created from the chaotic mess of our garret/closet which contains a ridiculous four-years-worth of baby and kid stuff. The baby clothes are laundered and waiting in a drawer. And the baby itself is head-down as confirmed by last week’s ultrasound and therefore I’ve not had to spend this week consulting moxibustionists. This is not to say that there aren’t a thousand things I want to/have to do before our baby arrives, but at least they don’t involve putting furniture together, matching tiny socks, or turning impossible babies. In a fundamental way, we are actually ready for the baby to come. And due to a crazy trick of nature, we’re even excited.

There wasn’t a lot of “birth preparation” going on the last time we went through this. We took the obligatory pre-natal class, but due to obvious defects in our personalities, Stuart and I just sat in the back and made sarcastic comments. And Harriet was stuck in the transverse-lie from so early on that it felt futile to make real arrangements for the natural birth we’d been hoping for. The “natural birth” itself was a choice we’d plucked out of the air without much context–it didn’t really seem possible that we’d come out of this whole pregnancy gig with something as miraculous as a baby anyway, and we were very much just going through the motions. When we were waiting for Harriet to be born, we were really just playing house.

This time however, it’s been so different, and I’ve been so much more deliberate in my choices. Even though my choices are the same, but this time I understand what they mean to me, to us. And it’s different too now that “us” is also Harriet. Having a little person with stakes in the arrival of another little person changes everything. She is also evidence that this baby is really going to happen, and our lingering memories of her babyhood make us quite aware of what we’re getting into.

“This time, it’s been different….” I keep writing this, and it should be self-evident, but the difference continues to fascinate me. It all feels a bit like Annie and Ernie McGilligan Spock and their fantastical trike ride: “In the same front yard/ Stood the same small tree;/ On the same brown table/ The same pot of tea.” And yet not the same at all. “How was it possible?/ Think of the shock…”

There is relief though this time in how much seems so different. My introduction to motherhood was such terrible time and we’ve still not quite shaken off the trauma of it all, and so I relish the idea that this time around we could make a different story. I think this was why it seemed particularly distressing last week when doubt was cast as to whether Baby was really head-down after all. And, “No way, no how,” said I. “I am not having another c-section.” For the past four weeks, I’ve been practising birthing hypnosis, and its impact became evident to me in how I responded to the potential breech situation. “I have courage, faith and patience,” I said. “This baby is going to turn. I am not going to book a c-section. I am going to go into labour. I am going to deliver this baby breech if I have to. This baby and my body know what they have to do.”

It’s quite true that I am determined that my birth story is going to be different this time. Not that the birth of Harriet was particularly troubling in itself, and recovery from c-section was remarkably easy, but I’ve told the story to myself over the past four years, it’s become clear to me that the c-section was responsible for some of the disconnect I felt from my baby after my birth. And I have gotten more angry as time as passed that I never saw her when they pulled her out of me, that I never saw her purple and sticky. She wasn’t shown to me until she’d been tidied up and wrapped in a blanket, which was only a few minutes, but I am sure I missed something terribly important in that gap. I read a copy of my operative report last week and it was fascinating (“interoperative finds: a live female”) but disturbing too that this thing had been done to me and I was so uninvolved. Unfathomable that the subject of the report was me.

(Last Tuesday when we thought Baby was breech, I was in a foul, foul mood. I’d also brought home a pamphlet from a cesarean support group that helps women spiritually heal from and grieve their c-section experiences. “What kind of bullshit is this?” I was exclaiming [at the dinner table, naturally] and my terrible husband with an evil glint in his eye said, “I think you should go.” I protested and he shrugged calmly: “You’ve been grieving your c-section for four years,” he said. My fist shook at the ceiling. “I am allowed,” I told him, “to grieve my c-section and find c-section support groups totally stupid.” I am a complicated person, and therefore this is my right.)

Harriet’s birth was booked two weeks before it happened, and it baffles me now that I opted for surgery so readily (though not before trying an ecv so there was a bit of effort on my part). But I think that my scheduled caesarean brought with it a bit of relief, some assurance, less of the great unknown. I’ve been sorry ever since that I never got a chance to go into labour though, and I’ve never shaken the feeling that I missed out on something monumental in my own birth as a mother. I went into her birth uttering inane phrases like, “The baby’s in charge,” but I never really meant it. If motherhood has taught me anything, it’s that I can out-stubborn the most unruly toddler. I was a fool to pretend that I could give in so easily, and this time I refuse to. I think I also said things like, “What matters is the result of a healthy baby and not how baby arrives,” which is a very easy thing to say if your body is not involved with baby’s arrival. Birth happens to Mother as much as Baby and to suppose that the mother’s experience somehow matters less is so completely insulting. This is also the thing that disappointed people say, as I know from experience, and also because my friends who’ve had amazing births will tell you straight that how their babies arrived matter to them very, very much. And I want to know what that’s like.

As much as one can ever prepare for something as unknown and unpredictable as childbirth, I feel as though we’ve made a valiant effort. Daily hypnosis practice, so much reading, the 3 hour pre-natal refresher we did last night which was so fantastic. I am very excited about the chance to try something I feared would always be out of reach to me. I can’t quite believe it really that anything could be so straightforward, and while I know that there is nothing straightforward about birth (just as I know that Harriet and I would have died had I not had access to a c-section with her in a transverse lie, and I know that these things don’t matter to some people as much as they’ve turned out to have mattered to me, which is just fine), I feel confident and supported in this being a road I can travel down.

And I now am excited and hopeful to discover just where that road leads.

April 21, 2013

Cottonopolis by Rachel Lebowitz

In Cottonopolis, Rachel Lebowitz both imagines and recreates the global trinity that was created by the 19th century cotton industry–in the American South where the cotton was grown by slave labour, in Lancashire England where the cotton was produced in mills with their belching chimneys and inhumane working conditions, and in India whose own textile trade was violently supplanted by the introduction of English imports. Through a series of prose poems and found poems, Lebowitz draws tight the lines between these distant places, their connections to lives lived locally and globally, and the connections between economics, industrialization, and story-telling. She plants seeds of connection between those nineteenth-century factories “[u]ntil the 1980s is a wasteland of old chimneys. Until the clothes are made in China…”. This is not a story as distant in place and time as it might seem.

In Cottonopolis, Rachel Lebowitz both imagines and recreates the global trinity that was created by the 19th century cotton industry–in the American South where the cotton was grown by slave labour, in Lancashire England where the cotton was produced in mills with their belching chimneys and inhumane working conditions, and in India whose own textile trade was violently supplanted by the introduction of English imports. Through a series of prose poems and found poems, Lebowitz draws tight the lines between these distant places, their connections to lives lived locally and globally, and the connections between economics, industrialization, and story-telling. She plants seeds of connection between those nineteenth-century factories “[u]ntil the 1980s is a wasteland of old chimneys. Until the clothes are made in China…”. This is not a story as distant in place and time as it might seem.

Many of the poems in Cottonopolis are classified as “Exhibits”, extrapolations of nursery rhymes, historical record, images, maps and items everyday and otherwise. Some echo the voices of those whose lives were made or broken by the cotton trade. The collection’s notes at the end of the book provide context and further explanation for what the poems themselves represent, and they add fascinating weight to this creative work and its stories.

But most remarkably for this book that uses language to build a museum is that the language itself is easily and unabashedly the work’s most remarkable aspect. I love the stories here, the history, but I can’t help but catch my mind on a line like “The trill of the/ robin, the trickle of the rill.” Or my favourite poem in the collection, “Exhibit 33: Muslin Dress” which turns language inside out in order to sew the whole world up into a tidy purse: “Here are the railway lines and there are the shipping/ lines. Here’s the factory line. The line of children in the/ mines. The chimney lines. There is the line: from the/ cotton gin to the Indian.”

April 17, 2013

Not just fine

“But something about new motherhood also darkened my worldview and made the thought of those cries more threatening. This is where you may be wondering if I’m just talking about post-partum depression, but the struggles I have in mind are unlikely to raise any significant red flags at the six-week check-up. And while, being raised in a family of psychologists, I certainly asked myself whether I might have PPD, I generally didn’t find that line of questioning helpful.

Don’t get me wrong—it’s an important question that we should keep asking ourselves and each other, and we should seek treatment unapologetically if the answer might be yes. But the problem with that question as our primaryapproach to the struggles of new motherhood is that it suggests that the post-partum experience itself is just fine, unless of course you have a legitimate clinical illness that distorts your perception of it. And the post-partum experience is not just fine. It is immensely, bizarrely complicated. It is, at various times and for various people, grueling and joyful and frightening and beautiful and disorienting and moving and horrible. There’s a lot going on there that will never make its way into the DSM V.”

-from “Before I Forget: What Nobody Remembers About New Motherhood” by Jody Peltason, whose standout line was “” We thought it would be sitcom-style hard.” Yes, indeed!

April 16, 2013

Upside down

I am quiet this week, mostly because I am reading Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings and that’s all I really want to do. What I don’t want to be doing is fretting about Baby being breech, but alas this seems to be my fret of the moment. I’m waiting for an ultrasound that will confirm either way. At least Baby is not transverse ala Harriet, which means the ending of this story has yet to written. Fingers crossed, but I’m pulling out all the stops this time, which is to say that I might discover what moxibustion is, and anything else that could possibly help turn the wee one. And if baby is breech, I will then be really concerned about why its bum is so head-like in its composition. What kind of anatomy is that?

I am quiet this week, mostly because I am reading Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings and that’s all I really want to do. What I don’t want to be doing is fretting about Baby being breech, but alas this seems to be my fret of the moment. I’m waiting for an ultrasound that will confirm either way. At least Baby is not transverse ala Harriet, which means the ending of this story has yet to written. Fingers crossed, but I’m pulling out all the stops this time, which is to say that I might discover what moxibustion is, and anything else that could possibly help turn the wee one. And if baby is breech, I will then be really concerned about why its bum is so head-like in its composition. What kind of anatomy is that?

In good news, I’ve worn capri pants and sandals two days in a row. Not entirely sensibly, but altogether happily. And at least the sun is shining.

April 14, 2013

The Douglas Notebooks by Christine Eddie

I was attracted to The Douglas Notebooks by Christine Eddie first because it is a beautiful object, a small and lovely book whose cover is adorned with blossoms and brambles that wind their way throughout the book entire. I was attracted to it also because the book in its original French had been the recipient of several literary awards, and French Quebec fiction is such unexplored territory for me. I welcome Goose Lane Editions publishing this English translation (by Sheila Fischman), widening my literary landscape as they did by publising Australian lit-award winner Night Street by Kristel Thornell last year. What a service to English Canadian readers to bring us these books we mightn’t encounter otherwise.

I was attracted to The Douglas Notebooks by Christine Eddie first because it is a beautiful object, a small and lovely book whose cover is adorned with blossoms and brambles that wind their way throughout the book entire. I was attracted to it also because the book in its original French had been the recipient of several literary awards, and French Quebec fiction is such unexplored territory for me. I welcome Goose Lane Editions publishing this English translation (by Sheila Fischman), widening my literary landscape as they did by publising Australian lit-award winner Night Street by Kristel Thornell last year. What a service to English Canadian readers to bring us these books we mightn’t encounter otherwise.

The Douglas Notebooks is branded “a fable”, which I’ll admit did not attract me to the book. I like my novels in the here and now, thank you very much, peopled by people instead of scurrying creatures. But “fable” here is a label loosely applied (for example, there are no talking rabbits, and apparently fables are meant to have morals but I’m not sure what the moral is here), and I often find that any novel I read in translation has an element of “fable” about it anyway, or at least sone kind of otherness. Here is not the novel in the shape I know it, I mean, and they always seem a little bit otherworldly. I have to judge a novel in translation on its own basis as well, and not based on what I understand “the novel” to be in my own limited experience of the form.

Which is not to say that The Douglas Notebooks is difficult to approach as a reader, or that I had to work hard to enjoy it. On the contrary, it was an easy book to slip inside, a fast and lively read. It seems out of place and out of time, situated in a village that doesn’t appear on a map and that for most of the book remains out of touch with progress and the rest of the world, though there are indications–the telltale tattoo on the schoolteacher’s arm, for example, which situates the book inside history. It’s the story of Romain, the son of a rich family who escapes them as soon as he can for a solitary life in the woods where he can be free. He enounters Elena, who has fled her violent homelife and made an apprenticeship with the village “pharmacist”, learning from her natural and herbal remedies for illness. But Elena leaves the pharmacist to make a life in the woods with Romain, who has since been remamed Douglas, for the fir tree. When Elena becomes pregnant, the couple feels as though their dreams will be fulfilled, and that with their child they will create a new world and a new way of life far removed from the trappings of society. But plans go wrong, and the result is heartbreak.

Brought into their fold are the local doctor who had loved Elena from afar, and the schoolteacher who had always been an outsider in the community, as well as a tamarack tree with mythical properties. In the centre of it all is the baby Rose, and the love that is wrapped around her like the brambles on the novel’s cover, both protection and a trap.

The Douglas Notebooks is a peculiar book, a tricky thing, and I’m not surely I’ve completely made sense of it yet. Why it’s a fable, for example, and what it means that this very rural book with all its natural elements (including, most wonderfully, a reverence for trees) is sort of structured cinematically, with the novel broken into sections with titles like “Wide Shot”, “Fast Motion” and “Close-Up” and even “Credits (in order of appearance)” as the book’s conclusion. But the unanswered questions are not unsatisfying, rather they underline for me in this slim and quiet book are just depths I haven’t plumbed yet.

April 12, 2013

Stick Figure Families and the Punch List

When I was pregnant with Harriet and in my third trimester, I started creating something called a “punch list”. Let’s just say I was not the picture of serenity. And as I move toward the final month of this pregnancy, the same old rage is taking hold, and today I’ve channelled it into a post at Bunch about the inexplicable nature of stick figure family car stickers. And I really do think that “fucking Fido Dido” is the best line I’ve ever written. Dare to argue, and I’ll likely punch you.