May 6, 2012

Author Interviews at Pickle Me This: Heather Birrell

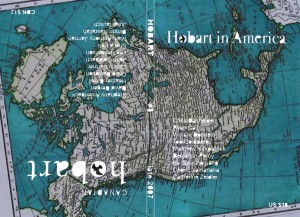

In February 2008, I spent one of the most perfect days of my entire life sitting on the grass in San Francisco’s Dolores Park, reading the journal Hobart in Canada/America, which I’d purchased the day before at the legendary City Lights Bookstore. And it was in that journal that I first encountered the work of Heather Birrell with the short story “My Friend Taisie”. Later on the next year, Heather turned up in the also-legendary “Salon de Refuses” issue of The New Quarterly, and I made a note on my blog that her story “Impossible to Die In Your Dreams” had been my favourite of the collection. (I also attended a panel discussion about the Salon of which Heather was a part. You can go here to see amusing pictures of Stuart and I looking extraordinarily bored).

In February 2008, I spent one of the most perfect days of my entire life sitting on the grass in San Francisco’s Dolores Park, reading the journal Hobart in Canada/America, which I’d purchased the day before at the legendary City Lights Bookstore. And it was in that journal that I first encountered the work of Heather Birrell with the short story “My Friend Taisie”. Later on the next year, Heather turned up in the also-legendary “Salon de Refuses” issue of The New Quarterly, and I made a note on my blog that her story “Impossible to Die In Your Dreams” had been my favourite of the collection. (I also attended a panel discussion about the Salon of which Heather was a part. You can go here to see amusing pictures of Stuart and I looking extraordinarily bored).

Heather emailed me after I’d mentioned her work on my blog. At the time she had a newborn daughter, and I was newly pregnant, and of motherhood she advised me: “time does shrivel, but it also expands in marvellous ways.” Which was true, but also a very kind lesson in restraint, I note in retrospect. Heather and I finally met in person in Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer’s kitchen one day about two years ago, and I’ve adored her steadily ever since.

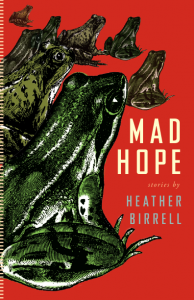

Heather Birrell is the author of the story collections Mad Hope and I know you are but what am I? Her work has been honoured with the Journey Prize for short fiction and the Edna Staebler Award for creative non-fiction, and has been shortlisted for both National and Western Magazine Awards. Birrell’s stories have appeared in many North American journals and anthologies, including Prism International, The New Quarterly, Descant, Matrix and Toronto Noir. She lives in Toronto with her husband and two daughters where she also teaches high school English.

Heather’s new book Mad Hope is mind-blowingly excellent. She very kindly answered my questions via email throughout this past April, beginning on a very sunny Easter weekend when both of us were ill.

I: “Where do you get your ideas” is a profoundly uninteresting question, but I want to come at it from a different angle. As I’m reading Mad Hope, I keep encountering these moments of profound identification where I want to write “Exactly” in the margins and underline it twice. And it’s for really oddly specific details, like the expressionless Iranian midwife, or following up a trip to the abortion clinic with Swiss Chalet. Or Jordan’s gait: “His hip dipped and his arm swung like a creature who had chosen– righteously– to remain less evolved.”

I: “Where do you get your ideas” is a profoundly uninteresting question, but I want to come at it from a different angle. As I’m reading Mad Hope, I keep encountering these moments of profound identification where I want to write “Exactly” in the margins and underline it twice. And it’s for really oddly specific details, like the expressionless Iranian midwife, or following up a trip to the abortion clinic with Swiss Chalet. Or Jordan’s gait: “His hip dipped and his arm swung like a creature who had chosen– righteously– to remain less evolved.”

And I know exactly who or what you’re talking about. I’ve probably even seen it, or read it– your stories also reference magazine articles I’ve encountered, email-forwards I was receiving as recently as last summer. Part of it is because so often you’re writing about– and so effectively too– the very city I live in, so of course I find it all familiar. But I’m still intrigued by how you employ the stuff of the world in your fiction, by your command of the material. And am I right to suppose that this very stuff– email forwards, post-abortion dipping sauces– is where you get your ideas from? Can you talk about your process?

HB: Oh, I’m so glad you had the ‘Exactly’ reaction! I love that sensation of somehow being known by the author as I read. I think those descriptions, expressions, shards of ‘true’ story you reference definitely serve as starting points for me but they don’t mean much until I’ve actually got some kind of more amorphous/abstract driving force in mind. Annie Dillard talks about ‘writing your own astonishment’ — I love that. There is such a range of issues, incidents, images that have the power to astonish — and they are different for everyone. I tend to think of my astonishments in the same way I might consider arguments if I were writing an essay — in other words, there’s something I’m trying not to prove but perhaps to convey in the best possible way, but my tools are less logical than metaphorical, narratorial.

In the story ‘Drowning…’ I wanted badly to write about suffocating mother-love, how the weight of mothering can be crushing at times… Then there were other bits and pieces preoccupying me: the time my husband nearly died of an asthma attack; an article I read about sole survivors of terrible catastrophes — that loneliness; what it means to teach kids with backgrounds very different from my own; and the email forward of the title of course! (This all sounds quite autobiographical, doesn’t it? But it isn’t always, and I’m not sure it even is here.)

So all these disparate threads, all these astonishments, somehow came together… How? I’m not being coy when I say I’m not really certain. It really does often feel that once a story is finished or near-finished I wiggle out of it like an old skin and it feels quite separate– an artifact unrelated to me.

I: These stories give the sense that you must read a lot, and widely. I could be wrong, but then I can’t imagine any way but reading for someone to learn, to know, as much about the world as your stories seem to convey you do. You mention elements of the autobiographical, yes, and I also see startling powers of observation at work (in particular in your portrayal of teenagers), but mostly Mad Hope seems to be the work of an author who reads widely. Is that true? What is the connection between your reading and your writing? What do you like to read?

I: These stories give the sense that you must read a lot, and widely. I could be wrong, but then I can’t imagine any way but reading for someone to learn, to know, as much about the world as your stories seem to convey you do. You mention elements of the autobiographical, yes, and I also see startling powers of observation at work (in particular in your portrayal of teenagers), but mostly Mad Hope seems to be the work of an author who reads widely. Is that true? What is the connection between your reading and your writing? What do you like to read?

HB: I am a reader, I am a reader, she intones quietly to herself. It has seemed for so long that my reading habits have been patchy and piecemeal. I have two small children; my sleep has been ragged for the last four years, so I suppose I have become more discriminating in some ways, but also hungry for narrative in any form as a means of escape from the more mundane aspects of motherhood. Because I often read in snatches, periodicals have been perfect lately — so I’ve been reading a lot of The New Yorker and The New Quarterly, and recently Brain, Child (which I discovered through your blog) — and big fat page turners that can be picked up, put down, and easily abandoned if need be.

Having said that, there are writers I return to (writers I could never abandon), writers I think of as unofficial mentors. Deborah Eisenberg. I adore her writing– it’s intricate, it’s smart, it’s funny, it’s city, it’s political. And her stories are long, which is more my rhythm when it comes to story reading and making. I tend to gravitate towards stories whose narrators are crouched in close to their characters, whose characters are complex, layered. I like unconventional story shapes too– stories that bulge out of themselves a little bit. Alice Munro, because her stories are masterful and mysterious. Anne Enright is a more recent discovery. I loved The Gathering, a novel that reads like a short story, and The Forgotten Waltz and her fabulous memoir Making Babies: Stumbling into Motherhood. Mary Gaitskill’s most recent collection, Don’t Cry, blew me away. It is so very fierce and wise. I find reading all of these writers incredibly permission-giving — ‘You can do that?’ they make me exclaim. It’s a wonderful and daunting feeling to have as a writer, to have the gauntlet thrown down in that way…

I am also incredibly inspired by the filmmaker Mike Leigh. I love how he manages moments of connection between his characters. His is a kitchen sink realism that recognizes the gritty, grimy, but also the gleaming moments that occur between people. And he does family dynamics — the secrets, the sadness, the omissions, the overwhelming love and sense of duty, the guilt, the fun, the fatigue — so very well. The way he builds to peaks of drama is so subtle and genuine — it’s really impressive. I also find him a very ‘moral’ artist, for want of a better term. He has such integrity, and his convictions are so present in his work but he is very seldom didactic. I think he’s a genius.

I: With what would you recommend your readers follow up Mad Hope? This is not a rhetorical question. In fact, this isn’t even really an interview question. But all I know is that I finished your book last weekend and the two short story collections I’ve read since (Other People We Married by Emma Straub and The Girl in the Flammable Skirt by Aimee Bender) have paled in comparison. Have you ruined reading for me, Heather Birrell? What would you advise me to do? (And I promise, we’re going to get back to talking about your book with the next question. Or that’s the plan, at least.)

HB: You are kind. And too smart and voracious a reader to be stymied by the likes of me. I’m pretty picky with short story collections now. I know what I like and don’t have a lot of patience for what I don’t. Plus I really do like to feel challenged. Jim Shepard’s Like You’d Understand Anyway is pretty great — the man goes to crazy, faraway places in his fiction and creates amazingly authentic worlds. And Amy Bloom’s Where the God of Love Hangs Out is the work of a writer who really understands people and acknowledges their mystery. She’s a taboo buster too, which I like. So I would advise you to have a cup a tea and a scone and keep on truckin’, Ms Kerry Clare.

I: I want to talk about your story ‘No One Else Really Wants to Listen’, which is structured as a series of posts on an online pregnancy forum. And the structure is so interesting because it allows for such a variety of points of view, believable absurdity and for clashes between characters that would happen nowhere else in the actual world. One of your characters writes, “And as for the internet—we have both been busy with it.” Do you think the internet and online forms of communication represent similar opportunity for writers using it in their fiction? What’s its potential?

I: I want to talk about your story ‘No One Else Really Wants to Listen’, which is structured as a series of posts on an online pregnancy forum. And the structure is so interesting because it allows for such a variety of points of view, believable absurdity and for clashes between characters that would happen nowhere else in the actual world. One of your characters writes, “And as for the internet—we have both been busy with it.” Do you think the internet and online forms of communication represent similar opportunity for writers using it in their fiction? What’s its potential?

HB: Short answer: Yes. People talk to each other through e-mail, online forums, texting, tweeting. And writers have always been interested in how we talk to and at each other. Having said that, the story you’re referring to didn’t start out as a ‘pregnancy forum’ story. One of the characters, Wings, arrived pretty fully formed on the page, and I wasn’t really sure what to do with her. She’s kind of obnoxious and over-the-top and I felt she needed someone or something to temper her in some way. At the time, I had been experimenting with using multiple points-of-view in my stories and simultaneously reading a lot of pregnancy/baby forums, so adding these voices seemed like a natural move. But it took me a while — and the nudging of my editor — to figure out that I didn’t have to represent everyone in my story just because everyone showed up in a free-for-all forum. I had to locate the story in the cacophony and then winnow it down a bit. And we decided we didn’t want the story to be too cluttered up by some of the formatting you find online — that in the end, it was the words that were important. But you’re right that the potential of this form is that it brings together people (characters) who might not otherwise meet, and that is terribly exciting.

As for the possibilities of the internet as a story making and delivery system — I think they are myriad. There are opportunities for a loose and nimble kind of creation — pass the story type stuff — online workshopping, and of course more traditional online publishing (Joyland). And there are apps out there right now, I’m thinking of Storyville in particular, that will deliver stories to your device in very readable formats. And I’m sure the possibilities will only increase as the technology changes and people change and grow with it. (I will confess here that my engagement with technology is sometimes reluctant, and I can only create new work using old school pen and paper. I think the world of the internets can be difficult to navigate and there are times I need to completely disengage from it in order to maintain any semblance of personal equilibrium.)

I: Truthfully, I too am more excited how writers are going to use the internet in their writing than the much-discussed idea of how the internet is going to make use of writing. Another really wonderful internet-based story is Jessica Westhead’s “And Also Sharks” which takes place in the comments of a blog. Stories like these give me great hope for stories of the future and the interesting shapes they might take.

But back to pen and paper, what about ‘BriannaSusannaAlana’ (which won the Journey Prize in 2006), another story featuring multiple points of view? Three sisters aged six, ten and thirteen, as divided as they are together, each reflecting on a neighbourhood murder, amongst other things. Did this story similarly begin as an experiment?

HB: Confession: I don’t actually remember why I decided to use the three sisters’ voices. (This is me leaving the story skin behind.) I suspect it had something to do with hearing some similarly sing-songy sibling names, and thinking about sisters, and their deep, sometimes problematic bonds. But I can tell you something that sparked one of the themes in the story. (This is me hijacking the interview and taking it into anecdote-land.) My sister and I (whose bonds are more loving than problematic) were running together in High Park when a couple of boys (a few years younger than the boys in BSA, maybe 10 or 11 years old) stopped and one of them called out to us: ‘Hey, my friend wants to do you bitches hard and anal!’

We were shocked, SHOCKED, and because we are both school teachers, our shock translated into immediate disciplinary action. We called the boys over, and, amazingly, they came, and stood in front of us, foot-scuffing and eyes down-casting, until they apologized. Then they took off, and one of them called back, all bravado, ‘He’s not really sorry!’ It made us laugh and shake our heads and I think we had to interrupt our run to go for a doughnut or something so we could talk about it. So that, and an article I’d recently read in the Globe & Mail about young teenage girls casually performing sexual favours, got me thinking about sexual precocity and the pornification of our culture and the kind of dangers and pressures young people today face. So the story became about danger and power and what it means to grow up female (and male in a more glancing way), and how our sense of our own power changes as we grow. But of course it’s about other things too.

I: I like anecdote-land. But your stories do have an edge, don’t they—“a hard edge, a large possibility of capture or injury.” You write so much about motherhood, marriage, parental love, quiet neighbourhoods, parkettes (although isn’t there always something sinister about a parkette?) but in the background, there is murder, suicide, pre-pubescent blowjobs, communist dictatorships. I speculate that the edge is what gives your stories so much of their power. What do you think? And have you tried to cultivate that edginess? Are you edgier than you used to be? Does a story have to be hardened to work?

HB: Oh, these are tough questions. Partly because it’s difficult for me to have a lot of perspective on the stories, especially considering they were written over a period of ten years or so — although of course they changed as I shaped them with my editor into a book. I do know that I didn’t try to cultivate any ‘edginess’ — and it seems here that you might mean edginess to mean the presence of trauma, whether it be on a personal or a political level. I don’t think a story has to be hardened to work. I think it has to have layers; I think it has to acknowledge complexity.

Am I edgier than I used to be? I think I just got older — friends split up from their partners, people died on me, I had kids, my courage grew when it came to certain convictions, but I became much more uncertain about a lot of other things… Having children especially made me vulnerable to darkness in a larger sense. In ‘Drowning Doesn’t Look Like Drowning’ the narrator says, “When I breastfed, I felt the world’s sadness in my throat. I wanted to spit it out and instead I had to swallow it.” So there’s that.

And on the flip side? A perhaps uncalled for optimism, which I hope is also present in the stories, and the title. It’s my yearning to believe in happy endings tempered by a more clear-headed resistance to them. I’m hopeful, yeah, but I know it’s crazy, mad in fact, to be hopeful. The world is round and it keeps turning, true, but I think it also has an edge!

I: Did you engage with motherhood in your writing before you had children? I think “My Friend Taisie” at least was written before you were a mother—right? After becoming a mother, did you have to go back and change things? Can motherhood be properly imagined?

I: Did you engage with motherhood in your writing before you had children? I think “My Friend Taisie” at least was written before you were a mother—right? After becoming a mother, did you have to go back and change things? Can motherhood be properly imagined?

HB: Yes, quite a few of the stories were written before I had children, but because I had children relatively late (the first at 37, the second at 40), I was pretty much surrounded by friends who had already become mothers, so I absorbed a lot through the osmosis that proximity and shared history allows. And I think I intuited quite a bit, or faked it anyway. (I didn’t go back and change anything specifically mothering related.) But of course, you can never truly know what it is to be a mother until you are one. Just like you can never truly know what it is to lose a loved one — at least not viscerally — until you have. But, but, but. I am a fiction writer and reader; I’m in the business of empathetic leaps. I like walking in other people’s shoes. And I think we must resist failures of imagination.

Having said that, I can tell you that the stories that were written post-children, ‘Frogs’, ‘Drowning…’, ‘Nobody else really wants to listen’, and ‘Geraldine and Jerome’ have a different understanding of what it means to love a child (your child) and the role of the mother, even if they are not always told from the point of view of a mother. I’m not sure I can qualify or quantify this difference, except to say that the pre-motherhood stories — let’s take ‘My Friend Taisie’ as an example — examine motherhood from a fascinated, slightly aghast stance (narrator Thomas’ discomfort and dismay at his friend Taisie’s pregnant self), whereas the post-motherhood ones are more stuck in the messy, bloody, leaky, tricky thick of it.

I: One of my favourite funny lines in this book that is packed with funny lines is in ‘BriannaSusannaAlana’ when twelve-year-old Alana is talking to her friend at Starbucks, twirling her hair while boys watch, and pretending she is acting naturally. “Dialogue, thought Alana. We’re doing dialogue.” And you are particularly good at doing dialogue yourself. Are you an avid eavesdropper? Does perfect dialogue overheard necessarily translate into good dialogue on the page? Is there a formula for getting it right?

HB: I’m not an avid eavesdropper, probably because I spend a lot of time with my mother, who is, and her means of eavesdropping mortifies me. But I guess I’m an inadvertent and (I’d like to think) stealthy, sometime eavesdropper. I don’t drive, so I spend a lot of time on public transit, which is perfect for picking up snippets of conversation. But perfect dialogue overheard rarely translates into good dialogue on the page. I will go so far as to say spoken dialogue is a different species from written dialogue — it has to be. Most of us are inefficient bumblers when we speak, and not many readers would have patience for that on the page. Plus — and this is an aesthetic thing — I can handle a certain level of artifice in my dialogue. I don’t mind if a character is going on a bit in a way that possibly seems stilted or stylized, as long as they have something interesting to say and the rhythm and language is beautiful. This is not a reason to speechify in stories — just a comment on the fact that characters are constructs, and even in ‘realistic’ stories, their parameters are elastic.

I’m not sure there’s any formula for getting dialogue right, but I will say that for me, dialogue — however absurd — must be rooted in character and pinned to the story by a meaningful connection to setting if it is to really work.

I: How does being a teacher make you a better writer? (Were you a teacher when you wrote your last collection? Has it changed your point of view?) Do your teaching and writing require a similar sympathy for teenage characters?

HB: I did some teaching here and there — mostly ESL to adults — when I was writing my first collection, but I didn’t become a full-time high school teacher until six years ago. I think it has changed my point of view, or maybe just my way of being. Teaching in a large Toronto public high school is challenging and wonderful and crazy-making and exhausting and rewarding. I thought I knew teenagers before I started teaching — I found my teenage years hard (who doesn’t?) and thought this gave me some expertise or access. But what I didn’t take into account was the fact that, well, teenagers are human beings, and human beings are insanely diverse as a species. So, while the particular life stage teens are immersed in might provide some basic back-story, that life-stage really is only a small part of who teens are. What I’m trying to say is that I know less about teenagers now than I did before I started teaching them — but I’m learning, I keep learning.

In terms of sympathy required for teenagers in teaching versus writing? I recently got the chance to read and talk to some high school Writer’s Craft students as a fiction writer — something I have roped many of my friends into doing (for free!) as a teacher. It is such a different experience being a guest writer. You really do have the freedom to be the wacky visiting aunt versus the strict, routinized mother. And I think that’s the difference I feel in the writing — I don’t have the same responsibility to my teenage characters (responsibility to mentor, to guide, to protect) as I do when I teach. So I feel an affinity for them, but not necessarily a sympathy, I suppose.

And teaching/writing balance — what a tricky thing! Teaching full-time in a high school is, I would venture to say, perhaps more all-consuming than many other teaching gigs. Part of it is the pace, and the marking, oh, the marking. And part of it is the sheer number of personal interactions required of a teacher during a school day — up to 180 students, colleagues, parents, administration. So that just tires a person out, and doesn’t leave much in the way of creative energy, never mind time. However. I often find it very refreshing to be around people who live (for the most part) very far from any kind of literary subculture. It means I can’t live a cloistered existence or take myself too seriously, and that the larger world, in its many guises, finds me and gives me a talking to every now and then. And teenagers can be so energizing too — they are often committed idealists and unselfconscious creators. Plus they’re fresh and funny and only pseudo-jaded. (Thanks for calling me funny, by the way. That was nice.)

I: Last question: Your book is getting great reviews. Do you believe them?

HB: Well, if I believe the good reviews, that means I have to believe the not-so-good ones too. So I wouldn’t say I believe them; I’d say I appreciate them. And the reviews I appreciate most are not necessarily the ones that are universally favourable — they are the reviews that have obviously taken time to engage seriously with the book, its ideas, its craft, its intentions. I have worked as a book reviewer and know it’s not always an easy gig, and that short story collections in particular can be a challenge to evaluate. But I also worked a long time on Mad Hope, and its road to publication was not smooth, so I would be lying if I said I didn’t care what people thought of the book, or if I didn’t tell you I feel relieved (sometimes to the point of tears — embarrassing!) that people — critics, neighbours, in-laws, bloggers!, friends — are responding in such a positive way. It’s why I write — to make connections, to make art.

There was so much I wanted to mention in my review that I didn’t, couldn’t. I’m glad you pinpointed things about certain stories in this interview! I hated feeling as though I was glossing over stories and not examining their meanings, but you touched on some things that bring the book to better light and give readers a closer look.

Great interview!

Wonderful interview. Agree entirely about Anne Enright’s The Gathering — it has the distilled language and emotional density that I too associate with short stories (but I loved that it was l-o-n-g). Claire Keegan’s stories have something of that too.