October 29, 2011

Author Interviews at Pickle Me This: Johanna Skibsrud

I was disappointed to have to decline the opportunity to have an interview in person with Johanna Skibsrud as part of her IFOA appearances in Toronto, and grateful when Skibsrud and her publishers agreed to an email interview instead. Though upon rereading her latest book This Will Be Difficult and Other Stories in preparation, I found myself discovering new depths to the stories that I hadn’t even glimpsed, which made me think that an interview might not even be necessary, that the answers to all my questions would be found within these stories themselves if I just looked hard enough…

I was disappointed to have to decline the opportunity to have an interview in person with Johanna Skibsrud as part of her IFOA appearances in Toronto, and grateful when Skibsrud and her publishers agreed to an email interview instead. Though upon rereading her latest book This Will Be Difficult and Other Stories in preparation, I found myself discovering new depths to the stories that I hadn’t even glimpsed, which made me think that an interview might not even be necessary, that the answers to all my questions would be found within these stories themselves if I just looked hard enough…

Johanna Skibsrud was born in Nova Scotia, and is currently completing her PhD in English Literature at the Université de Montréal, with a focus on the poetry of Wallace Stevens. Her first book of poetry, Late Nights With Wild Cowboys, was published in 2008 and shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Award for the best first book of poetry by a Canadian poet. A second book of poetry, I Do Not Think That I Could Love a Human Being, was published in April, 2010 and was short-listed for the Atlantic Poetry Prize. Her debut novel, The Sentimentalists, was awarded the 2010 Scotiabank Giller Prize, making her the youngest writer to ever win Canada’s most prestigious literary prize. You can read my review of her latest book This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories here.

I: So many of your stories are constructed around questions of theoretical concerns, around ideas of aesthetics, epistemology, language, time and place. When you sit down to a blank page, do you begin with these questions or with narrative? And how does fiction prove useful in generating answers?

JS: All my stories start from some small narrative kernel – an interesting anecdote (told to me or overheard), an image that begs a story, a memory. The ideas the stories encounter and engage with grow from that starting point. I am concerned with ideas, aesthetics, epistemology, language, time and place—very much so–but only because I am interested in people, and history; of the reality and intricacies of our relationships and every-day lives. I think it is impossible to separate philosophy and epistemology from the everyday—even though we often try. On a social, political and environmental level this impulse can be very dangerous.

I: Your prose style has divided your critics, and much attention has been paid to the construction of your sentences. Does this surprise you? How would you advise that a sentence be constructed? And echoing the words of Annie Dillard, do you like sentences? Does being a poet shape the way your make yours?

JS: I am flattered that so much attention has been paid to my language construction, but I often think too much is made of it. My writing style—especially in the stories—is not particularly complex, and hardly avant-garde. It is certainly meant to be read slowly and carefully, however, and according to a rhythm that reflects the difficulties and necessities of articulating the writing’s content. My ambition is not to offer the fact of the writing or of language itself, but it is certainly to pay attention to the implications of rhythm, style and language.

My advice regarding the writing of sentences would always be for the writer to follow their own inner sense of logic and rhythm while at the same time never failing to convey their meaning in the most direct possible way. Sometimes meaning is difficult—this takes more difficult sentences. I don’t mind it when sentences are complicated or difficult if they need to be, but I certainly don’t set out to make them that way. Just the opposite. A lot of (what I see as) the misunderstanding regarding the “difficulty” of my sentences stems from an unhealthy misconception as to the supposed “autonomy” of what people think of as “straight prose.” Prose is always as constructed as poetry is and often even more so because of how deeply invested it is in recreating the biases and blindnesses of everyday culture and language-use.

The idea that “poetry” is something that can be isolated, and stuck on the back shelf of the bookstore or library is disturbing to me. That said, the last thing that I would aspire to is what in Canada often gets called “poetic fiction”—the term is often synonymous with loose, floppy, or decorative language. Good poetry is the farthest thing from this: it is devastatingly crisp and succinct. It can say (what feels sometimes like) everything in just a single brief image, a single well-placed word. I think that all literature should be poetic in this sense. It should pay attention not only to the limitations but also to the inherent possibilities of its form.

I: What’s the genesis of the stories in This Will be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories? Were they written with an eye toward collection? Have some of these been published elsewhere, and where?

JS: The stories were all written between 2004 and 2007. I revised them after that incessantly. I tried to tighten them and bring out what I thought was most important to each. In 2008 I put them together as a collection and began to think of them more consciously in that way. The characters in all nine stories are united by the desire to push past—and overcome, when possible—the “limits” of perception, communication and understanding. The stories “belong together” in this way—each confronting what is “difficult to explain” in its different way. But the stories are certainly not intended to come together seamlessly in a comprehensive whole. Although some of the stories are explicitly connected and share a cast of characters (a network of American ex-patriates living in Paris), many are not. There are questions that get asked, or ideas that get introduced that remain—for the characters, just as they do for me—unanswered, unresolved.

Four of the stories were published previously. The first to be published was “The Electric Man.” It was brought out as a limited edition chapbook by Montreal’s Delirium Press, edited by Heather Jessup and Kate Hall. “The Limit” won The Stickman Review short story contest in 2005, and was published in their on-line journal. “This will be difficult to explain” (originally titled “This will be difficult to explain, and other stories”) was runner-up in a Glimmertrain Magazine contest and published in 2009. Finally, “French Lessons” appeared in Zoetrope: All Story in 2011. All of the stories that were previously published (except “French Lessons”) went through extensive overhauls before appearing in the book.

I: What do the stories in this book tell us about your preoccupations as a writer?

JS: Like me, the stories are preoccupied with the relationship between the abstract and concrete, the personal and the collective, the infinite and the everyday. Also, with limitations—both personal and historical. There is a desire to move past them in the stories, but also an awareness of the inevitable adherence, or return, to the limiting structures of culture and language.

I: In both “Angus’s Bull” and “Cleats”, there are moments in which mothers become disturbingly aware of their own children’s disturbing awareness of what’s going on in the world around them, to their openness to experience. The mothers seem to fear both their power and powerlessness at once. Which one do you imagine is most real and most terrifying?

I: In both “Angus’s Bull” and “Cleats”, there are moments in which mothers become disturbingly aware of their own children’s disturbing awareness of what’s going on in the world around them, to their openness to experience. The mothers seem to fear both their power and powerlessness at once. Which one do you imagine is most real and most terrifying?

JS: I think the two things cannot actually be separated. Just like with language. The moment you say something—the moment you settle on a single word to stand in for something that the word is not—you assert power over that named thing, but you also open it up to a (far greater) powerlessness: what it cannot say. It becomes instantly impossible for the named thing to speak for, or even directly to, what exceeds it, but at the same time that which exceeds it is afforded (against the newly circumscribed space of the word) a certain definition and form. It is possible that, at this point, genuine contact becomes more, rather than less possible. I think this must be true for parenting—and for politics, too, though I don’t have any personal experience practising either. We are constantly, in so many areas of life, forced to confront the limitations that arise due to our concentrated efforts to avoid, or move past, them. What is most terrifying is when powerlessness is not acknowledged; when power is asserted without recognition of its blind-spots, prejudices and limitations.

I: How does geography and topography influence how your characters think of place and themselves within that place? Is it like Daniel in “The Limit” who thinks that living in a place where the limits are clearly demarked enables you to better situate yourself, or like Martha in “Signac’s Boats” who is disappointed to find that limited perspectives are decidedly portable, and that she’d brought hers halfway across the world to Paris? Are limitations real or imposed/imagined?

JS: Again, both. Limitations are real because we imagine them that way. Reality and the imagination (just as Wallace Stevens spent his twin careers—as both poet and as insurance salesman—investigating) are inextricably intertwined. Art and literature can expand our personal, as well as our collective, imaginations. It can open up a space of empathy, and from this space can open the possibility of genuine action and change.

I: Setting is so essential to your work. Is it necessary for you to have experienced a place in order to set a story there?

JS: Not necessarily—though I do like to have some sense of the territory familiar to my characters. I haven’t been to Red Deer, Alberta, but I have been nearby. I think I have been almost everywhere else that I mention in the collection. I think that a writer can’t possibly avoid writing “from life” but should never feel, or be, limited by that. The material that any one of us draws from can be almost infinitely expanded, reinvented and reimagined, by combining our “real life” experiences in different ways.

I: For me, the definition of growing up lies in Martha’s revelation of love as a simplifying force, “when she’d thought it would have made her at the same time more integral, and more complex.” Do you think this is maturity? Is it a compromise?

JS: I do think that Martha’s revelation indicates the process of maturation that takes place over the story–and I don’t think it’s a compromise. So much of learning to live in the world is, I think, about learning to appreciate relationships and experience in “simple form.” To not will them into being something else, or a preparation for something else. Art helps us look at things in this way, I think—helps us learn how to look. It can help teach us how to appreciate things from a little distance, by thinking of them in relation to a wider frame of reference. The trick—and this is what Martha struggles with—is to not let this “simplicity” depreciate the value of the thing. To, instead, like a good poem or a painting (think of Frank O’Hara, or Georgia O’Keefe), allow that achieved simplicity to open the experience up—to reveal its inner richness, and complexity.

I: What books have been most formative in your experiences both as reader and as writer?

JS: The books that made me re-think what writing was capable of were (in order of their appearance in my life): Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, and Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire. Also, the work of the poets Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery and Lyn Hejinian. And you brought up Annie Dillard—I should mention also, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and For the Time Being.

I: What are you reading right now?

JS: Gulag: A History, by Anne Applebaum and David Foster Wallace’s Consider the Lobster.

October 27, 2011

Our Best Book from the library haul: Once Upon A Golden Apple

It was meant to be, really. A team of Canadian kid-lit legends Jean Little and Phoebe Gilman could only ever have been a success. Co-Author Maggie de Vries too– I’d read her memoir Missing Sarah years ago, and she’s had a successful career writing for children as well. But I am really baffled as to how it’s taken me so long to discover Once Upon a Golden Apple.

It was meant to be, really. A team of Canadian kid-lit legends Jean Little and Phoebe Gilman could only ever have been a success. Co-Author Maggie de Vries too– I’d read her memoir Missing Sarah years ago, and she’s had a successful career writing for children as well. But I am really baffled as to how it’s taken me so long to discover Once Upon a Golden Apple.

The very best book from the library in a bumper week of very good books from the library, and as soon as we began to read it, we just knew. It begins with a father telling his children a story, deviating from the familiar tropes much to their chagrin. “Once upon a golden apple?” “No!” the children shout. “Once upon a singing fiddle?” “No, no, no, no, no!” With each preposterous suggestion, the children become more and more agitated, and just when they think they’ve got their dad back on track, he breaks off again: there lived Goldilocks and the Seven Dwarfs? The princess kissed Humpty Dumpty? Who turned into a gingerbread boy? “No, no, no, no, no!”

Gilman’s children are adorable and Jillian Jiggs-ish, and we like the sausage-stealing dog that the storytellers are too en-rapt to notice. de Vries and Little finally manage to get the tale told, though not before making ridiculous suggestions that Harriet finds hilarious, and loves most of all because it’s always fun to be in on the joke, especially when you’re aged two.

October 26, 2011

The Submission by Amy Waldman

Amy Waldman’s The Submission begins with a jury making their final deliberations on how site of the September 11th terrorist attacks are to memorialized. Two years on from that fateful day, the nation is still raw, and anxious for healing to begin. No juror feels this more acutely than Claire Burwell, who lost her husband in the attacks, and who has been selected to serve representing the interests of the victim’s families. She rallies support around a design called The Garden, where she can imagine her children playing and which serves to honour the kind of man her husband was, as opposed to the more brutalist designs championed by other jury members. The Garden wins, the identity of its designer revealed, and he turns out to be a man called Mohammed Khan.

Amy Waldman’s The Submission begins with a jury making their final deliberations on how site of the September 11th terrorist attacks are to memorialized. Two years on from that fateful day, the nation is still raw, and anxious for healing to begin. No juror feels this more acutely than Claire Burwell, who lost her husband in the attacks, and who has been selected to serve representing the interests of the victim’s families. She rallies support around a design called The Garden, where she can imagine her children playing and which serves to honour the kind of man her husband was, as opposed to the more brutalist designs championed by other jury members. The Garden wins, the identity of its designer revealed, and he turns out to be a man called Mohammed Khan.

That the outrage sparked by this revelation seemed implausible to me mostly means that I don’t live properly in the world. A world in which the idea of a Ground Zero Mosque (which is neither a mosque nor at Ground Zero) sends people to the streets spouting hatred and threats of violence, which no doubt inspired some of what transpires in The Submission. The story shifts from Claire Burwell to Mohammed Khan himself, an architect American born-and-raised who is stunned to find himself in the spotlight, discussed on late night TV by right-wing windbags who speculate upon his motivations and foster rumours that this secular Muslim has extremist ties.

The story moves back and forth between these two characters and others, including a reporter who sees the story as an opportunity to further her own career, a Bangladeshi illegal alien who also lost her husband in the towers, the brother of a deceased firefighter who sees his newfound 9/11 status as a chance to finally make something of his life, the jury chair who’s caught between the jury and a state governor with elections on her mind.

Waldman is the former co-chief of the New York Times’ South Asia Bureau, and has the journalistic chops to tackle a story with such breadth, and also understands the spiral effect of story and the role the media plays in this process. It was on the side of fiction, however, where the story fell down for me, and in characterization more specifically. Claire Burwell herself is little more than a type, and she loses substance as the story progresses. Her supposed downfall is an ability to see the issue from all sides, but I failed to see her at all. Waldman tries to complicate her character by suggesting that all was not as well in her marriage as she presents to the outside world, but this significant storyline is never picked up again, and Claire herself ends up virtually disappearing from the novel about two thirds of the way through.

Another character weakly drawn was the firefighter’s brother, who turns out to have stupidity and alcoholism underlining his vitriol. It would have been more interesting to find a bigoted jingoist as intelligent and sure of himself as the characters on the other side. And not for the sake of fairness and balance, but rather because I think we’d be fooling ourselves if we explained away all the idiots as people who know they’re idiots deep down. In reality, there is a fiercer opposition to contend with.

But The Submission turns out to be a better book than it seems, and it turns out that what Waldman is writing about is not opposition at all. Khan digs in his heels and refuses to submit to the demands being put upon him from all sides– does he deny his background, assert himself as an American? But what of his understanding that being American means one has no need to deny his background? But who is he serving here? His country? His some-time faith? Himself? Claire Burwell is asking herself similar questions in her role as juror, and doubt is cast in her mind as to Khan’s intentions. Doubt he refuses to assuage because he’s never given her reason to mistrust him, so he holds back on principle, her mistrust doubly undermined. They’re turning in circles, and so is the whole world around them, violence and intensity escalating with each revolution, which culminates in a life that is tragically lost.

Waldman’s language doesn’t call attention to itself, though hers is a working prose that is doing things, so you’ll notice when you take your mind off the plot enough to pay attention. And similarly with the literary-ness of the novel, which creeps in and eventually outshines the plot. In the end, The Submission is a story both more universal and more specific than what the plot suggests, challenging, provocative and rich.

October 26, 2011

On re-watching Reality Bites

I was a deeply impressionable 14 years old when I first saw Reality Bites, and it came to define “cool” for the remainder of my teenage years and beyond: smoking, vintage dresses, ’70s nostalgia, passionate friendship, complicated relationships, the attractiveness of moody boys, and an obsession with self-obsession (“I’m making a documentary about my friends”). It taught us all to define irony so we wouldn’t be caught on the spot, it was David Spade at his finest (“Have a ‘tude weiner dude, all right.”), and it made angst so attractive, so important, essential. It made me pretend to like “My Sharona” (“Turn it up. You won’t be sorry”), had Crowded House on the soundtrack, sold torturous angst straight-up with U2’s “All I Want is You”, and it brought “Stay, I Missed You” into the world, which was the song that was playing when I was asked to dance by the coolest boy at summer camp (and, sadly, this was to be the peak of my romantic life for years and years and years).

I was a deeply impressionable 14 years old when I first saw Reality Bites, and it came to define “cool” for the remainder of my teenage years and beyond: smoking, vintage dresses, ’70s nostalgia, passionate friendship, complicated relationships, the attractiveness of moody boys, and an obsession with self-obsession (“I’m making a documentary about my friends”). It taught us all to define irony so we wouldn’t be caught on the spot, it was David Spade at his finest (“Have a ‘tude weiner dude, all right.”), and it made angst so attractive, so important, essential. It made me pretend to like “My Sharona” (“Turn it up. You won’t be sorry”), had Crowded House on the soundtrack, sold torturous angst straight-up with U2’s “All I Want is You”, and it brought “Stay, I Missed You” into the world, which was the song that was playing when I was asked to dance by the coolest boy at summer camp (and, sadly, this was to be the peak of my romantic life for years and years and years).

Because I couldn’t find Reality Bites at my local video store and the Toronto Public Library had not seen fit to update its VHS copy, it seemed like all my wishful thinking had conjured the Tenth Anniversary DVD I bought a few weeks ago at a yard sale for a dollar. I sat down to watch it last Friday night with an aim to craft a blog post about literary references in the film. Except that there weren’t any. Nobody reads in Reality Bites, not even Lelaina Pierce, college valedictorian, or Troy Dyer/Ethan Hawke, the greasy-haired philosophy drop-out. Who says things like, “I might do mean things, and I might hurt you. and I might run away without your permission… and you might hate me forever. And I know that that scares the shit out of you because I’m the only real thing that you have.” And what scares the shit out me is that fifteen years ago, I would have considered these lines incredibly romantic.

It’s true, all the movies I spent my teens and twenties thinking were romantic actually turned out to be fucked up stories about people who were emotionally crippled or mentally ill. Perhaps both forces were at work in Reality Bites (and really, we all know how things turned out for Winona). Reality Bites, the land where nobody reads, but people quote 1970s sitcom trivia at parties and Melrose Place is a cultural reference point. “Melrose Place is a really good show,” said Winona, and I’m not sure that I really agree, but I do think that Reality Bites is a really good movie. Still.

It’s an old, old story, contrary to what the newspapers would have you believe. It’s hard be out just of school, to be transitioning to adulthood, to be unemployed or underemployed, to not know where you want to go, and to have your actual options be even more limiting. To have goals but no idea how to make them realities. It’s hard to have ideals in the real world, to make things that matter, to settle down without settling, to decide who to fall in love, and when not to dress like a doily. It’s terrible to spend four years working towards adulthood, and then emerge into the world to find it utterly unwelcoming. To think that you’re not going to be able to have the kind of life your parents did, even if you’re not sure you want that life in the first place. To not get what you’ve been raised to think was your entitlement. To step out into the air and discover that you can’t fly.

We all know that each generation imagines that it discovered sex, but it’s true also that each imagines that disillusionment is something new. Reality Bites says otherwise: being 23 has always, always been terrible, but thankfully being 23 manages to not be the end of the world. It’s only the very beginning, and you learn.

October 23, 2011

New Kids Books We've Been Enjoying

Hooray for Amanda and her Alligator by Mo Willems: Willems is the best part of parenthood, his stories of Elephant & Piggie, Knuffle-Bunny and that notorious Pigeon never failing to delight, but I think that Amanda and her Alligator is my favourite yet. Amanda arrives home from the library with a stack of books, and her toy alligator has been waiting to play with her. Over 6 1/2 chapters, Amanda reads though her library stack (mostly nonfiction– my favourite is Climbing Things for Fun and Profit, or maybe Build It Yourself: Jet Packs!), and sets upon adventures with Alligator without ever leaving her room. The drawings are clear and simple, the stories too, and they’re heartwarming (though not ickily so) as they are funny.

Hooray for Amanda and her Alligator by Mo Willems: Willems is the best part of parenthood, his stories of Elephant & Piggie, Knuffle-Bunny and that notorious Pigeon never failing to delight, but I think that Amanda and her Alligator is my favourite yet. Amanda arrives home from the library with a stack of books, and her toy alligator has been waiting to play with her. Over 6 1/2 chapters, Amanda reads though her library stack (mostly nonfiction– my favourite is Climbing Things for Fun and Profit, or maybe Build It Yourself: Jet Packs!), and sets upon adventures with Alligator without ever leaving her room. The drawings are clear and simple, the stories too, and they’re heartwarming (though not ickily so) as they are funny.

A Few Blocks by Cybele Young: There is nothing simple about the illustrations of Cybele Young’s book A Few Blocks, in which imagination transforms the few blocks it takes to walk to school into a rich fantasy world. Ferdie doesn’t want to go school, but his sister Viola coaxes him along the way by creating adventure out of the ordinary, just as Young herself does through collage of her drawings which transform ordinary bits of neighbourhood into a giant sailing ship, a knight’s battleground, a superhero’s stomping ground.

A Daisy is a Daisy is a Daisy (except when it’s a girl’s name) by Linda Wolfsgruber: A Daisy… is a strange book that will probably appeal most to anyone with a flower name, or those of us who read baby name books as a pasttime. Gorgeously illustrated, Wolfsgruber shows that girls all over the world are named after flowers, and in all kinds of different languages. In Greek, Ianthe means violet, and she is Jolan in Hungarian, and Yolanda in Spanish. In Dutch, Mirte means Myrtle, she’s Hadassah in Hebrew, and Mirta in Spanish and Greek. “And Chloe is a very young sprout…”

A Daisy is a Daisy is a Daisy (except when it’s a girl’s name) by Linda Wolfsgruber: A Daisy… is a strange book that will probably appeal most to anyone with a flower name, or those of us who read baby name books as a pasttime. Gorgeously illustrated, Wolfsgruber shows that girls all over the world are named after flowers, and in all kinds of different languages. In Greek, Ianthe means violet, and she is Jolan in Hungarian, and Yolanda in Spanish. In Dutch, Mirte means Myrtle, she’s Hadassah in Hebrew, and Mirta in Spanish and Greek. “And Chloe is a very young sprout…”

Caramba and Henry by Marie-Louise Gay: “Stella and Sam?” said Harriet the first time she saw this book, and it doesn’t even matter that it’s not, because Marie-Louise Gay is always good. Though I don’t get him, Caramba, the cat who can’t fly. “But cats can’t fly!” I keep protesting, and people shout back at me, “That’s the point. Isn’t it awesome?” I’m not sure, but Harriet has never batted an eye, the story is great, the full page spreads absolutely breathtaking in their scope. Marie-Louise Gay is a treasure.

Molito by Rosemary Sullivan and Juan Optiz, illustration by Colleen Sullivan: Rosemary Sullivan is a friend of mine, and Harriet loves drums, so we were set to love this book from the get-go. The story of a little mole who dares to climb up from the underworld and discovers a whole other world out there of music, dancing and light. But losing himself to this world would require losing the friends and music he made in his life underground, so Molito seeks a way to make a connection between the two. “Above and below/ In the dark and the light/ Upside down and upside right/ Below your feet and above your head/ There’s just one world./ There’s just one world.” Colleen Sullivan’s illustrations are delightful in their detail, and the book also comes with a CD of Molito’s music.

Molito by Rosemary Sullivan and Juan Optiz, illustration by Colleen Sullivan: Rosemary Sullivan is a friend of mine, and Harriet loves drums, so we were set to love this book from the get-go. The story of a little mole who dares to climb up from the underworld and discovers a whole other world out there of music, dancing and light. But losing himself to this world would require losing the friends and music he made in his life underground, so Molito seeks a way to make a connection between the two. “Above and below/ In the dark and the light/ Upside down and upside right/ Below your feet and above your head/ There’s just one world./ There’s just one world.” Colleen Sullivan’s illustrations are delightful in their detail, and the book also comes with a CD of Molito’s music.

Bumble-Ardy by Maurice Sendak: I’m more confused by Maurice Sendak than I am by Caramba, actually, but my appreciation for Sendak’s new book Bumble-Ardy was underlined when I read his interview in The Paris Review. Harriet just likes the pigs, the birthday party and the pictures. The rhyme is a bit ripped off from Ludwig Bemelmans, reminding us of a someone we once knew who left the house at half-past nine in rain or shine, but I’m less confused than I was with Outside Over There, and there is depth here that reader young and old can tumble into and wander around in. Every time I read it, I appreciate it more.

October 21, 2011

Not believing the hype

One if my favourite books ever is Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, and I’d be a rich woman if I had a nickel for every person I’ve ever encountered who’s refused to read it because it’s story of a teenage murderer. (And oh, by the way, it isn’t. We Need to Talk About Kevin is the story of a marriage. But you have to read the book three times to figure that out). For some reason, however, I feel free to cast disdain on these non-readers, on their deliberate steps away from the difficult, uncomfortable questions put forth by provocative literature, while I continue to oblige my own prejudices. Perhaps because my own prejudices are not quite so vague, so open-ended. Give me a well-written teenage murderer any day, but force me to read a book about a dog and I’ll pull my eyes out.

One if my favourite books ever is Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, and I’d be a rich woman if I had a nickel for every person I’ve ever encountered who’s refused to read it because it’s story of a teenage murderer. (And oh, by the way, it isn’t. We Need to Talk About Kevin is the story of a marriage. But you have to read the book three times to figure that out). For some reason, however, I feel free to cast disdain on these non-readers, on their deliberate steps away from the difficult, uncomfortable questions put forth by provocative literature, while I continue to oblige my own prejudices. Perhaps because my own prejudices are not quite so vague, so open-ended. Give me a well-written teenage murderer any day, but force me to read a book about a dog and I’ll pull my eyes out.

Note, however, that here I insist on being as inconsistent as I ever was– a look through my recentish reading confirms that I liked Andrew O’Hagan’s Maf the Dog book, and both Our Spoons Came From Woolworths and Quickening, both of which had dogs on their cover, plus I even attended a literary dog exhibition.

But dogs are really only the tip of the iceberg, and somehow the fates have conspired to make the rest of the iceberg the most hyped books of the season. Because do you know what I hate more than I hate books about dogs? That would be books about circuses, of course, and I don’t like books about cowboys, and not even “books about”, but there might be nothing I hate more in the whole wide world more than I hate jazz. Which has pretty much left me nothing in the whole world to read… except for the 73 books I have before me on my TBR shelf. So maybe you can see why I’m not too bothered.

So dare I cave to the pressure of the hype? Is the hype any less ridiculous than my own stupid literary prejudices? Though I do pay attention to awards lists (and go Zsuzsi Gartner and Lynn Coady, by the way. Your books rocked my soul), and I’m grateful to the books they point me to, I’m certainly not going to read all lauded books for the sake of the act. This is a lesson I perhaps learned the time I read Vernon God Little.

There are books I should read, no doubt. This is the reason I read The Wings of the Dove and Great Expectations this year, and why my slow trip through The Collected John Cheever is ongoing. But I refused to be obliged to read a book until at least ten years has determined it’s still worth my while. And depending on how posterity has treated it, I might pick it up, dog or no dog, cowboy or no cowboy. Unless it’s a book about a circus.

October 20, 2011

Our Best Book from the library haul: Ira Sleeps Over by Bernard Waber

We’re having a bit of an affair with Bernard Waber’s Lyle the Crocodile books, which are so good, and Harriet loves them. Though they’re a bit long, and I’m not sure every toddler would have the patience, so I was delighted when we took out a new book by Waber, Ira Sleeps Over, and discovered that here was a less text-laden book that I could heartily recommend.

We’re having a bit of an affair with Bernard Waber’s Lyle the Crocodile books, which are so good, and Harriet loves them. Though they’re a bit long, and I’m not sure every toddler would have the patience, so I was delighted when we took out a new book by Waber, Ira Sleeps Over, and discovered that here was a less text-laden book that I could heartily recommend.

I love these ’60s/70s’ children’s books (Waber reminds me of Louise Fitzhugh and Judith Viorst), their sharpness, and their irreverance. Plus, Waber is an author/illustrator, and the best of these people can elevate the picture book to a whole other level. Must confess up front though that I am disproportionately amused that this book contains the line, “That night, Reggie showed me his junk.” But that’s only because you’re the one with the sick mind.

Ira has been invited to a sleepover at his friend Reggie’s house. He’s excited, but a little nervous, and he goes back and forth between these emotions in passages with his parents and meddlesome sister– the repetitive language will especially appeal to young readers. When Ira wonders if he should bring his teddy bear with him? Would Reggie laugh?: “”He won’t laugh,” said my mother. “He won’t laugh,” said my father. “He’ll laugh,” said my sister.”” I particularly love the family dynamics, very Free to Be You and Me with Mom and Dad making dinner together, both parents pursuing interests beyond their parental roles as Dad practicising the cello in the evening, and Mom hides behind the newspaper.

Eventually the sleepover arrives, and Reggie and Ira have fun together. Reggie shows Ira his junk collection in a fabulous two page spread that might have inspired a young Marthe Jocelyn to go on to write Hannah’s Collections. The boys start to tell ghost stories, and the moral of the book turns out to be that a need for comfort is universal, that teddy bears are much less controversial than a small boy might think.

October 19, 2011

Once You Break a Knuckle by D.W. Wilson

On Monday, I compared D.W. Wilson to Alice Munro in a Twitter post, and got called out by a few people for being off the mark. Upon rereading my post, I could see how it my point was misconstrued– I forgot that Alice Munro comparisons must necessarily denote Greatness, and I didn’t mean to do that. D.W. Wilson’s short story collection Once You Break a Knuckle reads very much like a first book, lacking in precision and assurance, but there is promise here, evidence of a good writer whose best work is still before him. Which really, in a first book, sometimes, is all that a reader can ask for.

On Monday, I compared D.W. Wilson to Alice Munro in a Twitter post, and got called out by a few people for being off the mark. Upon rereading my post, I could see how it my point was misconstrued– I forgot that Alice Munro comparisons must necessarily denote Greatness, and I didn’t mean to do that. D.W. Wilson’s short story collection Once You Break a Knuckle reads very much like a first book, lacking in precision and assurance, but there is promise here, evidence of a good writer whose best work is still before him. Which really, in a first book, sometimes, is all that a reader can ask for.

But I stand by my Munro comparison, though I know I should be comparing Wilson to Raymond Carver and commenting on the raw, violent masculinity afoot. What I couldn’t stop thinking of, however, as I read the stories about Will Crease sparring with police constable father John was Flo & Rose, and the Royal Beatings,that violent dynamic of family life with love at its root. About class and how both families are of and apart from their communities, and about the communities themselves, Wilson’ s real-life town of Invermere evoked similarly to Munro’s Hanratty (or Jubilee). And how Wilson seems preoccupied with certain ideas, characters and story lines, returning to them again and again to examine them from various angles, as Munro has also done throughout her story collections and throughout her entire career.

I agree with Steven Beattie’s comment that the Will Crease stories in this book have the feel of ” chapters in a novel searching for a through-line”. My favourite story in the collection was a Will Crease story, but the one that seemed most discrete from the rest, “Don’t Touch The Ground,” about a young person’s act of vengeance with tragic consequences. The collection’s longest story “Valley Echo” was also strong, and its structure reminded me of Munro’s ability to telescope time.

There is a class division throughout the collection between “the hicks” so feared by Will and his friends, and the down-and-outs themselves– I found myself longing for a connection as in a story like Alexander MacLeod’s “Light Lifting”, which would have shed considerable light on both sides. Though there were other kinds of links, most particularly the Oldsmobile 1955 Rocket 88, which turns up with a few different drivers at its wheel, recurring characters, and repeated expressions about broken knuckles and picking fights, and kicking cows as well.

I got hung up on some of the metaphors– no matter how many times I read the line, “I’ve got fibrous red hair and a jaw tapered like a rugby ball,” I still can’t see what he’s saying. Then there was the line about “wineglass-sized breasts”, and I just don’t really think people should compare breasts to anything. But I underlined good parts too– my favourite passage was, “And she was attracted to him– if he didn’t, for instance, need someone to pull his head from the clouds– then Ray knew why: broken people are drawn to broken people. That’s the love life he had to look forward to with Kelly: a three-legged race.”

There is a bleakness to these stories, a sense of inevitability that Wilson goes to such pains to make clear that he takes us decades into the future, and the future is a lot like now is. In a town like Invermere, nothing ever changes, but Wilson that shows story happens all the same.

October 17, 2011

Our visit to Little Island Comics

By pure coincidence, this is my third post in a row dealing with islands and oceans. And this is an especially joyful post because the gist of it is that a new children’s bookstore has just opened up around the corner from my house. Little Island Comics is brought to you by the people behind The Beguiling, and is the first comic book store in North America catering exclusively to children. They cater not just with comics either, but also with a wide variety of beautiful books that seem to mostly just have gorgeous illustrations in common. We stopped by on Saturday and the store was full to bursting with children of all ages (and their parents). Though the big kids in the store seemed enthralled by the wares, we also found much to choose from for the Harriet set, and settled on a Tiny Titans comic, and Maurice Sendak’s new book Bumble-Ardy. Staff were approachable, knowledgeable, and thrilled with all the activity going on in the store. And there’s bound to be more of it– Little Island Comics has a space in the back where comic workshops and other events will be conducted. Check their blog to stay abreast of happenings. We’re looking forward to our next visit!

By pure coincidence, this is my third post in a row dealing with islands and oceans. And this is an especially joyful post because the gist of it is that a new children’s bookstore has just opened up around the corner from my house. Little Island Comics is brought to you by the people behind The Beguiling, and is the first comic book store in North America catering exclusively to children. They cater not just with comics either, but also with a wide variety of beautiful books that seem to mostly just have gorgeous illustrations in common. We stopped by on Saturday and the store was full to bursting with children of all ages (and their parents). Though the big kids in the store seemed enthralled by the wares, we also found much to choose from for the Harriet set, and settled on a Tiny Titans comic, and Maurice Sendak’s new book Bumble-Ardy. Staff were approachable, knowledgeable, and thrilled with all the activity going on in the store. And there’s bound to be more of it– Little Island Comics has a space in the back where comic workshops and other events will be conducted. Check their blog to stay abreast of happenings. We’re looking forward to our next visit!

*Check out their profile from last weekend’s Globe and Mail.

October 16, 2011

Not Being on a Boat by Esme Claire Keith

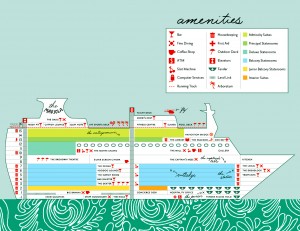

There was so much right about Esme Claire Keith’s novel Not Being on a Boat that I was planning to review it here anyway, even though there was one thing quite wrong. The one thing being its length, of course, and that being trapped in the mind of her Mr. Rutledge for 350 pages was just too much, but that it was so thoroughly too much was because her Mr. Rutledge was so spotlessly executed. A divorced retiree jacked up on the force of his own consumer power, he has bid farewell to the world and boarded the good ship Mariola to sail off into the sunset. Equipped with two tuxedos and a taste for the finer things in life, he’s expecting good value for his money and some fine conversation with the other passengers in the Captain’s Mess.

There was so much right about Esme Claire Keith’s novel Not Being on a Boat that I was planning to review it here anyway, even though there was one thing quite wrong. The one thing being its length, of course, and that being trapped in the mind of her Mr. Rutledge for 350 pages was just too much, but that it was so thoroughly too much was because her Mr. Rutledge was so spotlessly executed. A divorced retiree jacked up on the force of his own consumer power, he has bid farewell to the world and boarded the good ship Mariola to sail off into the sunset. Equipped with two tuxedos and a taste for the finer things in life, he’s expecting good value for his money and some fine conversation with the other passengers in the Captain’s Mess.

The devil is in the details, however, all of which Rutledge notices, astute businessman (and borderline autistic) that he is, forever on the lookout for number one. But such details and this perspective doesn’t make for great reading, not 350 pages of it, as we learn about the ship’s laundry procedures, and what’s available on the menu, and the historical facts even Rutledge fast tires of as delivered by guides giving tours at the ship’s ports of call. The flawlessness of Keith’s narrative makes reading really hard-going, though things outside Rutledge’s head are certainly interesting: we receive glimpses of the distopian civilization that Rutledge has left behind him, and the problems come aboard the Mariola when one day a group of passengers and some crew fail to return from a port of call. Suddenly, the ship’s standards begin slipping, supplies are getting low, communications are shut down from the outside world, and the problems of the outside world are creeping in through the portholes.

The devil is in the details, however, all of which Rutledge notices, astute businessman (and borderline autistic) that he is, forever on the lookout for number one. But such details and this perspective doesn’t make for great reading, not 350 pages of it, as we learn about the ship’s laundry procedures, and what’s available on the menu, and the historical facts even Rutledge fast tires of as delivered by guides giving tours at the ship’s ports of call. The flawlessness of Keith’s narrative makes reading really hard-going, though things outside Rutledge’s head are certainly interesting: we receive glimpses of the distopian civilization that Rutledge has left behind him, and the problems come aboard the Mariola when one day a group of passengers and some crew fail to return from a port of call. Suddenly, the ship’s standards begin slipping, supplies are getting low, communications are shut down from the outside world, and the problems of the outside world are creeping in through the portholes.

The novel concludes with an end-of-days scenario that had me furious: 350 pages for this? But as the fury wore off, I decided to write about the book anyway because Keith’s control of her project was so impeccable, and also because I’m not sure there was any other way she could have ended it. Not Being on a Boat is a marvelous satire of consumer culture and luxury tourism, so smart and funny, deadpan and sharp. (It is also beautifully designed by kisscut book design, including the map of the boat I discovered under the back flap). And sometimes a flawed book really can still portend the debut of a really great writer, so though “less is more” would really go a long way here, I’d say Keith is one to keep an eye on, and I’d check out what she comes up with next.