November 10, 2011

"I wrote two books watching her clothes blow on those lines."

Before I had a baby, somebody told me how she wished she’d played with her children more. That she’d spent their childhoods rushing from one thing to another, and never took the time get down on the floor and engage with what they do on their own level. So I decided that her experience would be a lesson for me, just like I’d decided that any sleepless nights with my new baby be an opportunity for me to revel in her nearness. And then my baby was born, an occasion I came to define as “the day I discovered all my limits within arms’ length”. The sleepless nights were an opportunity for me to imagine murdering my husband, more than anything else. And it would turn out that when it came to play, I wouldn’t do much better.

Before I had a baby, somebody told me how she wished she’d played with her children more. That she’d spent their childhoods rushing from one thing to another, and never took the time get down on the floor and engage with what they do on their own level. So I decided that her experience would be a lesson for me, just like I’d decided that any sleepless nights with my new baby be an opportunity for me to revel in her nearness. And then my baby was born, an occasion I came to define as “the day I discovered all my limits within arms’ length”. The sleepless nights were an opportunity for me to imagine murdering my husband, more than anything else. And it would turn out that when it came to play, I wouldn’t do much better.

Now just being with my daughter, I can do. Ours is not a particularly harried pace. We spent a lot of timing talking over pancakes, and lying sprawled on the floor staring at the ceiling. I like our conversations, I love brushing her hair, I think that holding her hand as we walk down the street is perhaps the great privilege of my existence. I really do like to be with my daughter, but I find playing insufferably dull most of the time. It’s boring, and after about five rounds of “playing farm”, “making a cake” (which involves piles of crayons), or “playing doctor” (whose stethoscope is actually a USB cable), I tend to drop out. I find her play absolutely fascinating to watch, but not to engage with it. Which is a huge reason why I appreciate picture books and stories, actually, and why we read so many of them– it’s the one activity of which neither of us ever tires.

In a recent interview promoting her new book Blue Nights, Joan Didion notes that as a mother of a young child, she had been “totally wrapped up in keeping some time free for myself.” And I read that and thought, yes, that is precisely what motherhood is. Because once the baby’s arrived, she’s there, and there’s no fighting it– there’s no need to be wrapped up in that. How much I am enjoying the experience of motherhood has always been directly proportionate to the time I have to spend away from it. And to be totally wrapped in keeping this time free is not the same as being a bad or neglectful mother. To be so wrapped up is to be going against the flow, of course, swimming upstream, yes, but you’re still in the water. You’re always and forever in the water, which is precisely the point.

In a recent interview promoting her new book Blue Nights, Joan Didion notes that as a mother of a young child, she had been “totally wrapped up in keeping some time free for myself.” And I read that and thought, yes, that is precisely what motherhood is. Because once the baby’s arrived, she’s there, and there’s no fighting it– there’s no need to be wrapped up in that. How much I am enjoying the experience of motherhood has always been directly proportionate to the time I have to spend away from it. And to be totally wrapped in keeping this time free is not the same as being a bad or neglectful mother. To be so wrapped up is to be going against the flow, of course, swimming upstream, yes, but you’re still in the water. You’re always and forever in the water, which is precisely the point.

(I always think of the son in JM Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello, whining at the bare silence of his mother’s office door. And I’ve always thought that the son was a bit of an asshole, since I read the book, which was long before I had a child of my own. I’ve always thought that learning from an early age that one is not the centre of any universe, let alone his mother’s, is probably a healthy thing for anybody.)

Love pours out from the pages of Blue Nights, for the difficult Quintana Roo from her even more difficult mother. Life is like this. Motherhood is also like this, as Didion examines old photographs of her daughter growing up in Malibu: “The clothes of course are familiar./ I had for a while seen them every day, washed them, hung them to blow in the wind on the clotheslines outside my office window./ I wrote two books watching her clothes blow on those lines./ Brush your teeth, brush your hair, shush I’m working.”

We had a wonderful morning at our house today, a backyard buried in leaves presenting the greatest opportunity. To be outside together working on a project we would both equally enjoy, the best mix of practical and whimsical, and neither of us would be bored. We filled two big bags with leaves, and there will be much more of this in the days to come, as the tree appears as fully dressed as ever. And then we walked to the grocery store to pick up some milk, which is rare because we usually stroller-it everywhere. I am usually in too much of a hurry, but not this morning, this lovely, leafy, golden morning. And just when the walk home appeared to be taking forever and the end of my patience was in sight, Harriet demanded to be scooped up and carried, which was fine with me, however awkward in coordination with 4 litres of milk, but these are the things we manage. We got home, and made a batch of Carrie Snyder’s granola bars, which are delicious. The whole arrangement sort of glorious, because it felt like we were two people rather than parent and child, relating on a somewhat-even keel, in spite of the disparity in our heights.

We had a wonderful morning at our house today, a backyard buried in leaves presenting the greatest opportunity. To be outside together working on a project we would both equally enjoy, the best mix of practical and whimsical, and neither of us would be bored. We filled two big bags with leaves, and there will be much more of this in the days to come, as the tree appears as fully dressed as ever. And then we walked to the grocery store to pick up some milk, which is rare because we usually stroller-it everywhere. I am usually in too much of a hurry, but not this morning, this lovely, leafy, golden morning. And just when the walk home appeared to be taking forever and the end of my patience was in sight, Harriet demanded to be scooped up and carried, which was fine with me, however awkward in coordination with 4 litres of milk, but these are the things we manage. We got home, and made a batch of Carrie Snyder’s granola bars, which are delicious. The whole arrangement sort of glorious, because it felt like we were two people rather than parent and child, relating on a somewhat-even keel, in spite of the disparity in our heights.

But see, she’s sleeping now, and I’ve got a cup of tea, and the time and space to write it all down, and therein lies the key to my happiness.

November 9, 2011

Still Reading Through the Alphabet: Under Covers

Though I’m drowning in new releases, I am still making my way through the TBR alphabet, currently mired in the unending Ms. And finally got to Jamaica Inn by Daphne Du Maurier (who probably doesn’t belong in the Ms, but who’s to say?). I do love that I have a hideous old paperback with Jane Seymour on its cover– Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman! And that my paperback is a TV mini-series tie-in– how often does that happen these days? Who could ever have imagined that the cover would ever be dated too, hmm? Though I supposed that datedness is the object of a trade paperback, to be read to shreds, battered, and relegated to the dustbin. Except that mine overcame the odds and I scooped it up at a used book sale once upon a time. Must say that it’s my least favourite of the DuMaurier’s I’ve read so far– though the ending surprised me, the main character and the backstory had much less substance than Rebecca or My Cousin Rachel. The plot was less compelling, but there were good bits.

Though I’m drowning in new releases, I am still making my way through the TBR alphabet, currently mired in the unending Ms. And finally got to Jamaica Inn by Daphne Du Maurier (who probably doesn’t belong in the Ms, but who’s to say?). I do love that I have a hideous old paperback with Jane Seymour on its cover– Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman! And that my paperback is a TV mini-series tie-in– how often does that happen these days? Who could ever have imagined that the cover would ever be dated too, hmm? Though I supposed that datedness is the object of a trade paperback, to be read to shreds, battered, and relegated to the dustbin. Except that mine overcame the odds and I scooped it up at a used book sale once upon a time. Must say that it’s my least favourite of the DuMaurier’s I’ve read so far– though the ending surprised me, the main character and the backstory had much less substance than Rebecca or My Cousin Rachel. The plot was less compelling, but there were good bits.

I also read Joyce Maynard’s Labor Day, which everyone is except me has read already. And which everyone has told me is so very, very good, but I didn’t believe them. Partly it was the gross peaches cover (and those hands are all wrong!), the Jodi Picoult blurb (I am not only a snob, but one who once read a book by Jodi Picoult, so I’ve got cred), and the title, which made think that this was a book all about birthing. But it turned out to be completely different than I expected, including really, really good. And perhaps it’s the New England thing, but it read like a book a less-weird John Irving might have written, and someone would have slapped an altogether different cover on that one, don’t you think? Does this look like a book that’s narrated by a teenage boy? But it is, and it’s great, and I’m glad I finally read it, and I’m just sorry that so many other people as prejudiced as I am never will.

November 9, 2011

Discovered: Brain, Child Magazine

I’ve been living under a rock, it seems, and so it was only on Monday that a copy of Brain, Child Magazine first appeared in my mailbox. And it’s like I’m right back there years ago discovering MS, Bust, and Bitch for the very first time. All those magazines that changed the way I see myself and the world, that were the turning point when I became a feminist. But after a while, I didn’t need them anymore, and it’s been a really long time since I read indie magazines (um, apart from the five literary magazines that turn up in my mailbox quarterly or more. I do my part, no fear).

I’ve been living under a rock, it seems, and so it was only on Monday that a copy of Brain, Child Magazine first appeared in my mailbox. And it’s like I’m right back there years ago discovering MS, Bust, and Bitch for the very first time. All those magazines that changed the way I see myself and the world, that were the turning point when I became a feminist. But after a while, I didn’t need them anymore, and it’s been a really long time since I read indie magazines (um, apart from the five literary magazines that turn up in my mailbox quarterly or more. I do my part, no fear).

But in terms of reading about parenting, it’s been all mainstream over here, and I tired of it much faster than I tired of the others. And not until I finally got my mitts on Brain, Child did I discover that I’ve been parched, starved for story. For essays that run off the page, and are written so well, which challenge and move me (but not too much for the former. Brain, Child seems infinitely readable, even for the bleary-minded. I read the whole thing cover to cover in 36 hours, part of it in the bathtub. It’s like that).

The magazine appeared on my limited radar when the wonderful Stephany Aulenback mentioned her essay published within about her adventures on Ancestry.com– a hilarious piece about her discovery of her children’s alleged royal lineage. And then I read “Glass Half Full”: has telling the “truth” about motherhood been taken to the point of dishonesty? And this was when I decided to buy a subscription, because I wanted a parenting magazine that had Rachel Cusk as a touchstone (and which doesn’t advertise boatloads of unnecessary crap, like that ridiculous stroller that turns into a tricycle, or denim diapers).

I loved the essay about the woman with chicken pox in her third trimester, and the scene where her two-year-old is finally allowed to see her after weeks of separation– the primal way in which the little girl reclaims her mother. In another essay, a mother accompanies her small daughter to her birth mother’s sister’s wedding– and contemplates the ways in which the birth mother will always be disappointing. Or another in which a woman thinks about the meaning of “inappropriate” and links it to her daughters’ discomfort with her body after her mastectomy.

I love that there is fiction here, and loooong book reviews, and that the magazine ends with a poem that is funny. I love the mothercentricity of the magazine’s approach, the literary quality of the writing, that the essays offer more questions than answers, and also that I subscribed for my Fall issue so late that it won’t be long until the Winter one arrives.

November 7, 2011

Dadolescence by Bob Armstrong

Dadolescence is one of a few books I’ve read this year– along with Kate Christensen’s The Astral, Shari LaPena’s Happiness Economics and even the story “Summer of the Flesh Eaters” from Zsuzsi Gartner’s Better Living Through Plastic Explosives— that considers what it is to be a man apart from traditional institutions of masculinity. Is a man still a man when his wife is his family’s main breadwinner, when he’s spent his career chasing after artistic dreams that haven’t come true, when he’s become decidedly middle-aged and no longer attracts admiring glances from women (if he even ever did)? As outliers on the spectrum of masculinity, the men in the novels I’ve mentioned are dumped into a catch-all house-husband/stay-at-home dad catagory, but they fit in here as awkwardly as they do everywhere.

Dadolescence is one of a few books I’ve read this year– along with Kate Christensen’s The Astral, Shari LaPena’s Happiness Economics and even the story “Summer of the Flesh Eaters” from Zsuzsi Gartner’s Better Living Through Plastic Explosives— that considers what it is to be a man apart from traditional institutions of masculinity. Is a man still a man when his wife is his family’s main breadwinner, when he’s spent his career chasing after artistic dreams that haven’t come true, when he’s become decidedly middle-aged and no longer attracts admiring glances from women (if he even ever did)? As outliers on the spectrum of masculinity, the men in the novels I’ve mentioned are dumped into a catch-all house-husband/stay-at-home dad catagory, but they fit in here as awkwardly as they do everywhere.

Though Bob Armstrong’s Bill Angus is a stay-at-home-dad, his son is old enough and independent enough that the novel doesn’t fully examine that experience. Rather, Dadolescence considers what happens to every stay-at-home parent when they begin to realize that their role is becoming obsolete. They’ve stayed home for the kids all these years: now what? Though Bill avoids addressing this question throughout the novel, deluding himself into thinking instead that the PhD thesis in anthropology he’s been not writing for years is ever going to be finished.

His stay-at-home dad neighbour/colleagues have similar diversions. Dave has become obsessed with remodeling his house in order to add resale value, digging up floors and knocking down walls (sometimes load-bearing). The tipping point arrives when he decides to built a turret on his 1950s’ bungalow. Meanwhile, Mark tells implausible stories of his work on a cattle-ranch, as a police officer, influencing Bono, and now he’s gunning for an astrophysics contract with NASA. And Bill is taking this all in, imagining himself turning his neighbours’ experiences into an anthropological study of modern masculinity, supposing himself to be removed from what he is observing, though also terrified that he isn’t.

Meanwhile in his preoccupation with his neighbours, Bill finds himself neglecting his household duties, disappointing his twelve-year old son, and (almost) failing to notice that his wife is drifting away from him.

Dadolescence was written from Armstrong’s play Tits on a Bull, which was performed at the 2007 Winnipeg Fringe Festival. Which means that the voice of the hapless Bill comes through with enormous humour, though it overwhelms the novel itself at times and tells much more than it shows. Bill himself is also such a passive character that the plot lags with him at the helm, and in order to be resolved resorts to some screwballish hinjinx. Nothing is subtle here, everything a little bit over the top, but it’s as funny as it’s meant to be, and more than once, I laughed out loud.

In Dadolescence, Armstrong has captured that difficult period in the life of every Gen-Xer, when it becomes time to unload the vinyl evidence of one’s “youthful audio anglophilia” at a garage sale, and finally begin to grow up.

November 6, 2011

My favourite day of the year

It really is my favourite day of the year, this one with 25 hours in it. It meant that this morning we could get up and be lazy, and still be at the AGO for their 10:00 opening. And that it was ROM Members Day at the AGO meant that we got in free, which meant no fretting about getting one’s money’s worth, and that we could hang out in the gallery for an hour or so, and then retire to the cafe (and this, plus the lazy mornings, are exactly how we roll). Then this afternoon, I spent four hours working on tomorrow’s Giller Prize post for Canadian Bookshelf, and by the time I was finished, it was dark outside. And though I love summer madly and despair the winter days, I do love those dark evenings with my family tucked inside our house, the lights a golden glow. Particularly because we had wine leftover from last night’s dinner with friends, and it was delicious. (As had been the dinner itself, meat lasagna from Tessa Kiros’ Apples for Jam, the cookbook that never fails). The overall goodness of the day only underlined by the glorious weather, sunshine so warm that I didn’t even need to wear my new hat (but I did anyway, because I made it myself. I have the biggest head in the universe). And that tomorrow we’ll wake up at 7:00, and it finally won’ t be dark out.

It really is my favourite day of the year, this one with 25 hours in it. It meant that this morning we could get up and be lazy, and still be at the AGO for their 10:00 opening. And that it was ROM Members Day at the AGO meant that we got in free, which meant no fretting about getting one’s money’s worth, and that we could hang out in the gallery for an hour or so, and then retire to the cafe (and this, plus the lazy mornings, are exactly how we roll). Then this afternoon, I spent four hours working on tomorrow’s Giller Prize post for Canadian Bookshelf, and by the time I was finished, it was dark outside. And though I love summer madly and despair the winter days, I do love those dark evenings with my family tucked inside our house, the lights a golden glow. Particularly because we had wine leftover from last night’s dinner with friends, and it was delicious. (As had been the dinner itself, meat lasagna from Tessa Kiros’ Apples for Jam, the cookbook that never fails). The overall goodness of the day only underlined by the glorious weather, sunshine so warm that I didn’t even need to wear my new hat (but I did anyway, because I made it myself. I have the biggest head in the universe). And that tomorrow we’ll wake up at 7:00, and it finally won’ t be dark out.

- Check out my friend Nathalie’s time-change blog post, Got An Extra Hour? Read Books With Clocks.

November 6, 2011

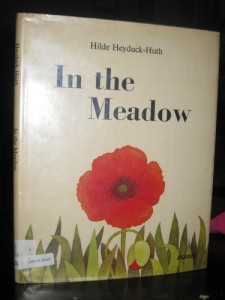

Our Best Book from the Library Haul: In the Meadow by Hilde Heyduck-Huth

There wasn’t an obvious candidate for our Best Book this week, and this aged book, which was translated from German by Patricia Crampton, did not seem like an obvious contender. But you never know with Best Books really, and it’s anybody’s guess how children will respond. Halfway through our first reading of In the Meadow, the story about a dung beetle navigating a forest of grass, Harriet was absolutely captivated.When the beetle encountered his ladybug relatives,

There wasn’t an obvious candidate for our Best Book this week, and this aged book, which was translated from German by Patricia Crampton, did not seem like an obvious contender. But you never know with Best Books really, and it’s anybody’s guess how children will respond. Halfway through our first reading of In the Meadow, the story about a dung beetle navigating a forest of grass, Harriet was absolutely captivated.When the beetle encountered his ladybug relatives,  Harriet insisted on digging her stuffed ladybug out of her toybox. “Ladybugs are a kind of beetle,” I explained to her, but she heard it differently, and has been telling us ever since how her ladybug is a “kind-of beetle”. The illustrations in this book are detailed and beautiful. Hilde Heyduck-Huth has a website (in German) and from the links on this page you get a sense of the fascinating things she’s been up to in her illustration career (inc. an edition of Kahil Gibran’s The Prophet).

Harriet insisted on digging her stuffed ladybug out of her toybox. “Ladybugs are a kind of beetle,” I explained to her, but she heard it differently, and has been telling us ever since how her ladybug is a “kind-of beetle”. The illustrations in this book are detailed and beautiful. Hilde Heyduck-Huth has a website (in German) and from the links on this page you get a sense of the fascinating things she’s been up to in her illustration career (inc. an edition of Kahil Gibran’s The Prophet).

November 3, 2011

What I found: Childcraft- The How & Why Library

Blog fodder is something I’ve been thinking about as I finish up writing my lectures for SCS 2114, and I’ve been thinking about how often I stumble upon mine by the side of the road. On Tuesday, it was a stack of encyclopedias from the Childcraft- The How & Why Library, an edition published in 1987. There’s a volume of fairy tales and nursery rhymes, another of contemporary stories (Amelia Bedelia, Where the Wild Things Are, etc.), one of art projects, another about dates, festivals and celebrations, one about How Things Work, and Numbers and Math. We’ll have to edit Space and the Universe so Harriet understands that there is no such thing as Pluto, but so much of the content here will never go out of date, the books are in perfect condition (except for the page that Harriet ripped), are still attractive-looking, and (best of all) they don’t smell like a basement. (We might ignore the parenting guide in Volume 15 though, with its topical chapters of latchkey kids and working mothers.)

Blog fodder is something I’ve been thinking about as I finish up writing my lectures for SCS 2114, and I’ve been thinking about how often I stumble upon mine by the side of the road. On Tuesday, it was a stack of encyclopedias from the Childcraft- The How & Why Library, an edition published in 1987. There’s a volume of fairy tales and nursery rhymes, another of contemporary stories (Amelia Bedelia, Where the Wild Things Are, etc.), one of art projects, another about dates, festivals and celebrations, one about How Things Work, and Numbers and Math. We’ll have to edit Space and the Universe so Harriet understands that there is no such thing as Pluto, but so much of the content here will never go out of date, the books are in perfect condition (except for the page that Harriet ripped), are still attractive-looking, and (best of all) they don’t smell like a basement. (We might ignore the parenting guide in Volume 15 though, with its topical chapters of latchkey kids and working mothers.)

I’ve been longing for an encyclopedia in the same way I wish I knew how to use my sewing machine. I love its containment of the universe, the order of its numbered spines, its place of honour on the shelf, and that if anyone in our household ever wants to know what a cloud is and the internet’s down, it’s no problem. I love that you can open any volume to a random place, and discover something completely fascinating.

The downside to all this, however, I discovered after lugging the whole stack home (while pushing a stroller whose basket can no longer accommodate books after too many gluttonous trips to the library, though that I carried a stack of encyclopedias home really might be the most remarkable part of this story): two volumes are missing! Volume 3 Stories and Poems, and Volume 7 Story of the Sea might just have to tracked down and purchased online for the sake of completion.

November 2, 2011

The Vicious Circle Reads Saving Rome by Megan K. Williams

I’m coming out of first-person plural here, because I loved Saving Rome by Megan K. Williams without reservation. I’m coming to the tail-end of the busiest month I’ve had in years, and the space I’d carved out to read this book– sitting on the couch during Harriet’s nap times, holding the book open with my feet while I furiously knit up this hat— was like a gift to myself every day last week. The reading was a pleasure, the stories so diverse in their approaches to their subject, so strong, convincing, so funny, and underlined a lot of experiences from my expat days. I don’t think I’d enjoyed any other book as much that we’ve read for our club, unless it was a book written by an English novelist in the 1950s. It’s one of the best books I’ve read lately, and I’d recommend it wholeheartedly.

I’m coming out of first-person plural here, because I loved Saving Rome by Megan K. Williams without reservation. I’m coming to the tail-end of the busiest month I’ve had in years, and the space I’d carved out to read this book– sitting on the couch during Harriet’s nap times, holding the book open with my feet while I furiously knit up this hat— was like a gift to myself every day last week. The reading was a pleasure, the stories so diverse in their approaches to their subject, so strong, convincing, so funny, and underlined a lot of experiences from my expat days. I don’t think I’d enjoyed any other book as much that we’ve read for our club, unless it was a book written by an English novelist in the 1950s. It’s one of the best books I’ve read lately, and I’d recommend it wholeheartedly.

What being in a book club has taught me, however, is that there’s no telling with taste. And that taste is so much what we’re talking about when we’re talking about books, no matter how much we couch our arguments in aesthetics. I also know that being in a book club has made me a better book reviewer (and it has made being a book reviewer that much harder. I second-guess myself more often now. Which, for a book reviewer, is a good thing.)

Anyway, reactions were mixed across the board as The Vicious Circle assembled in the St. Lawrence neighbourhood of Toronto last Saturday morning. We were also dressed as literary characters for Halloween (and one of us was dressed as a genre)– I was wearing a 99 cent 54DD bra from Honest Eds, stuffed with Harriet’s plush balls as Georgina Hogg from The Comforters, but not the sexy version. There was lots of delicious food, and plenty of gossip, and even a baby, then we got down to the book.

It was boring, said one of us, and another of us was aghast. One of us had struggled for a while with not liking the characters, which was disturbing because she’s a better reader than that, but then she realized that she just didn’t care about the characters. That they were boring. That they were living in Rome, but weren’t engaged with the setting at all. They could have been anywhere. “But that’s just the point!” said another one of us, pulling out the old “I’ve got personal experience of it” trump-card, which is a stupid trump-card actually, because a book isn’t good just because it reminds me of when I lived in Japan.

The point though, that one of us continued, is that living abroad and being engaged with a place is exhausting, and can unsustainable, and that Williams’ stories reflect the frustration, rage, ennui and struggle of one who is living where she doesn’t belong. Fair enough, says another of us, but the stories were all the same, the same kinds of people, the same kind of stasis, the non-endings. Even though the characters were married, single, gay, parents, variously? But they all sounded the same, was the problem. It was also noted that the gay characters didn’t get to have sex, that Williams shut the door on their encounter, when it was flung wide open for heterosexual couples.

There was no consensus on best stories, though “Pets” probably was closest to it, particularly the strange pet shop owner. It was noted that Williams’ Italian characters were more interesting than her expat characters who seemed more like stereotypes. Though we also liked the story “Saving Rome for Someone Special” about the perils of living abroad with friends-of-friends always showing up to sleep on your sofa, and what happens when a girl arrives who is certifiably insane. There was some debate as to whether Jonathan is pathetic as he’s presented, and why exactly he’s presented as pathetic. It was felt the ending petered out the same way they all did.

We liked the wit though, the dialogue. We liked that a hamster died of being squeezed to death. We liked the end of “Motion”: “But that day, when her eyes finally fell on it, on Frank’s arrow made of dried corn stalks pointing right, she felt a startling surge of gratitude for being linked this way to another human being, and she followed it.” We weren’t nuts about the two stories that weren’t set in Rome. Some of us liked the first story very much, its “acerbic wit” and others found it frustratingly “mommish”. But then no, exclaims another. The point was what was going on below the surface, how she kept laughing at inappropriate moments and was on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

And so it continued, volleys back and forth over coffee and apple cake, and cupcakes, and guacamole (because there is always guacamole), and always, as always, a splendid time was had.

November 1, 2011

Blue Nights by Joan Didion

“When we talk about mortality, we are talking about our children,” writes Joan Didion in her new book Blue Nights. And in fact, when Didion is talking about any one thing in this book, she is usually talking about something else, a point which she spends much of the book considering– her struggles of late as a writer to be direct, to get to the point. In particularly in regards to her daughter Quintana, and when Joan Didion is talking about Quintana, she can’t avoid talking about mortality, about the “death of promise”; Quintana died in 2005 at the age of 39, not long after her father’s sudden death one evening at the dinner table (the year after which Didion chronicled in her previous memoir).

“When we talk about mortality, we are talking about our children,” writes Joan Didion in her new book Blue Nights. And in fact, when Didion is talking about any one thing in this book, she is usually talking about something else, a point which she spends much of the book considering– her struggles of late as a writer to be direct, to get to the point. In particularly in regards to her daughter Quintana, and when Joan Didion is talking about Quintana, she can’t avoid talking about mortality, about the “death of promise”; Quintana died in 2005 at the age of 39, not long after her father’s sudden death one evening at the dinner table (the year after which Didion chronicled in her previous memoir).

When Didion is talking about Quintana, she’s not only talking about her daughter’s mortality, but about her own. The years since her daughter’s death have brought about a general ill-health, a growing frailty that she has struggled to address with various health professionals with very little success. And then it occurs to her– she is 75 years old. Perhaps this alone is the problem, and there is no “fix”. And this has never occurred to her before, that she would eventually (or quite suddenly) get old. “Time passes… Could it be that I never believed it?”

This from a woman whose writing has always been drenched in nostalgia, who from the time she picked up a pen has been eulogizing the way we don’t live anymore and the “all that” she’d said good-bye to. That Joan Didion has never believed time to pass is impossible to consider, except that maybe she never considered herself passing along with it.

“The common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I,'” wrote Didion in “On Keeping a Notebook,” from her 1968 collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, except now she’s 75 and that common denominator seems less a sure foundation. In the same essay, she’d also written, “Remember what it was to be me. That was always the point.” And now more than 40 years later, she doesn’t want to remember anymore.

She writes that well-meaning friends try to assure her through her loss: “You have your memories”. She writes that for many years, she fetishized these memories, saving everything– drawers and cupboards stuffed, mementos pinned to the walls– believing that they would help keep people “fully present”. And when she most important people in her life are lost, she’s left with “detritus of this misplaced belief.” She writes that remembering the past only reminds her of how much she failed to appreciate what she had in the first place.

And when she writes about failing to appreciate what she had, she’s writing about Quintana. She’s writing about her own relationship to her daughter (who happened to be adopted), which is similar to any mother’s relationships to her child, adopted or otherwise. Contemplating that newborn bundle: “What if I fail to take care of this baby? What if this baby fails to thrive, what if this baby fails to love me?… what if I fail to love this baby?”

Except that Quintana doesn’t just “happen to be adopted”, and Didion has realized that failing to acknowledge this was a significant failing of her own as a mother. That Quintana’s mental health problems (which are referred to obliquely; this is no expose) could have been rooted in her own fears of abandonment. That what the “choice narrative” so favoured towards 1960s adoptees left unsaid was the underside of adoptive parents’ choosing, why a child was up for choosing in the first place. And Didion notes that she could never treat this underside, that she chose to avoid it because to highlight her daughter’s origins would be to expose her own terrible fear– that this miraculous child who’d been placed in her arms would somehow be stolen away from her. To acknowledge Quintana’s fear of abandonment, to acknowledge the fact of Quintana herself, would have been to clarify her own feelings and fears about her daughter, which Didion could never bring herself to do.

Except that she’s lost her now, a worst fear realized, and her daughter’s death has served to bring her own death closer. And without her daughter to survive her, when she dies she will “Pass into nothingness,” a phrase from Keats’ she discovers in one of Quintana’s high school exercise books. A phrase that had resonated with the teenaged depressive Quintana, another side of her that Didion had never allowed herself to understand. A side that she’s coming to understand now as she contemplates the end of her own life, and how much her daughter’s sense of mortality and her actual mortality have illuminated her own.

She finds it hard to be direct now. She offers a passage from her novel The Last Thing He Wanted to show the way her prose used to come so easily, that she wrote it like the rhythm it was. But she can’t do that now. She can’t find the right words, she can’t get to the point, she keeps falling, and forgetting, and getting frailer all the time. The point is slipping farther away. But it’s not that she is afraid to die. She writes that she’s getting so she’s afraid not to die, but it’s not that, and it’s not the writing either.

She writes, “The fear is for what is still to be lost,” and she’s writing about her memories of her daughter. “How could I not still need that child with me?” She writes, “there is no day in her life on which I do not see her.”

October 31, 2011

Tricks and Treats

Harriet was Tilly Witch for Halloween this year, which was a grand success, except for the blip around 4:30 when she decided that she going to wear her Easter Bunny ears instead of the witch hat, and I had to go upstairs and have a moment to myself in order to avoid murdering her. By the time I’d calmed down, the bunny ears were abandoned, and the rest of the evening was splendid, resulting in a bucketful of treats.

Harriet was Tilly Witch for Halloween this year, which was a grand success, except for the blip around 4:30 when she decided that she going to wear her Easter Bunny ears instead of the witch hat, and I had to go upstairs and have a moment to myself in order to avoid murdering her. By the time I’d calmed down, the bunny ears were abandoned, and the rest of the evening was splendid, resulting in a bucketful of treats.

Over at Canadian Bookshelf, I’ve written “I am Not At Peace: Ghosts and Haunting in Canadian Fiction”, exploring the spookier side of CanLit. And if you’re not subscribing to the blog, you should. There’s great new stuff up three days a week.