November 23, 2011

What to expect

“They named me Ruth Frances Beatrice Brennan, and took me home. They days blended together, one into another with no distinctions. The crying, the feeding, the changing, the chafing, the washing, the soothing, the burping, the singing, the sleeping, the waking. As new parents, James and Elspeth were surprised by their fatigue, as well as my dismissal of it. If someone had told them what to expect (and no one had), they hadn’t taken it in, and now, rather than forging ahead, they were rolling and rolling.

Sometimes Elspeth hung over me with smears of purple under her eyes, the skin there loose and fine, like something that would tear easily. She begged me to understand, though she knew she asked too much of me. Just as I asked too much of her, and him, and they of each other. James formed a habit of going to get things before they were needed, because it made him feel helpful and also allowed him to escape, just briefly, what he’d never expected to have to endure.” –Kristen den Hartog, And Me Among Them

November 23, 2011

Today, we get to celebrate

Today, we get to celebrate our beloved, who is now as old as I am. Who’s doing amazing things in his professional day-job life, and in his professional-freelance life, and who as a husband and father is second to none. He is truly adored, and we are very lucky to have him. We are also very lucky because his birthday is another excuse to eat this wonderful Oreo Ice Cream Pie.

Today, we get to celebrate our beloved, who is now as old as I am. Who’s doing amazing things in his professional day-job life, and in his professional-freelance life, and who as a husband and father is second to none. He is truly adored, and we are very lucky to have him. We are also very lucky because his birthday is another excuse to eat this wonderful Oreo Ice Cream Pie.

November 20, 2011

T is for Toronto

Just in case I wasn’t totally steeped in Toronto already, having just finished the Eatons’ biography, they scheduled the Santa Claus Parade for this weekend. We’ve never been before, even though it goes by right around the corner from our house, but we made it out this year because Harriet’s at the perfect age to be overwhelmed by the magic of it all. She enjoyed the whole thing, found the giant Barbie appropriately disturbing, and said that the Mother Goose float was her favourite of all of them. Which is unsurprising really, because we’re Mother Goose mad around our house these days.

Just in case I wasn’t totally steeped in Toronto already, having just finished the Eatons’ biography, they scheduled the Santa Claus Parade for this weekend. We’ve never been before, even though it goes by right around the corner from our house, but we made it out this year because Harriet’s at the perfect age to be overwhelmed by the magic of it all. She enjoyed the whole thing, found the giant Barbie appropriately disturbing, and said that the Mother Goose float was her favourite of all of them. Which is unsurprising really, because we’re Mother Goose mad around our house these days.

Since Harriet arrived in our lives, we’ve come into possession of no less than four Mother Goose Books, which you might think is overkill but each offers something slightly different– we’ve got Scott Gustafson’s stunningly gorgeous Favourite Nursery Rhymes from Mother Goose which is handled with care, a second-hand copy of Iona Opie’s My Very First Mother Goose which is loved with wild abandon, Richard Scarry’s Best Mother Goose Ever with its illustrations guaranteed to transfix wee ones (and also its admirably subversive violent edge), and the nice and portable Sing a Song of Mother Goose by Barbara Reid.

I’ve also come ’round to “Bat bat come under my hat…” and no longer think it’s stupid.

November 17, 2011

Our Best Book of the Library Haul: The Elephant and the Bad Baby

It was a very good week for library books this week, mostly because we showed up at the library on Monday not long after the librarian had replenished the featured book shelf, and then we took most of them. (Is this bad library etiquette? I’m never sure. Though even if I was, I’d do it anyway.) Stand-outs included the wonderful Dear Baobab by Cheryl Foggo, and Ella May and the Wishing Stone by Cary Fagan, and I think that if Harriet were older, either one of these would have taken the prize. But because Harriet is only 2, our best book of the week was not from the featured shelf at all, it was The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont and Raymond Briggs, which we turned up while hanging out in the stacks in the vicinity of Judith Viors and Bernard Waber.

It was a very good week for library books this week, mostly because we showed up at the library on Monday not long after the librarian had replenished the featured book shelf, and then we took most of them. (Is this bad library etiquette? I’m never sure. Though even if I was, I’d do it anyway.) Stand-outs included the wonderful Dear Baobab by Cheryl Foggo, and Ella May and the Wishing Stone by Cary Fagan, and I think that if Harriet were older, either one of these would have taken the prize. But because Harriet is only 2, our best book of the week was not from the featured shelf at all, it was The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont and Raymond Briggs, which we turned up while hanging out in the stacks in the vicinity of Judith Viors and Bernard Waber.

The Elephant and the Bad Baby delights the parts of us that worship all things Albergh, and we think that Alan and Janet must have read this one back in the day. I love it most because just why the baby is “the bad baby” is never really explained (except once where he doesn’t say please), because I love elephants, and because when the elephant runs down the street, it goes, “rumpata, rumpata, rumpata” (of course!). The baby and the elephant run through town stealing things from shopkeepers, from sausages to lollypops (and maybe this is why the baby is the bad baby? Though the elephant really led him on), and being chased by the shopkeepers (some bearing cleavers), and then they all sort of work it out and end up back at the bad baby’s house where his mother makes them pancakes, and they sit around the table with a big teapot in the middle. Also, the elephant is drinking milk from a bucket, which Harriet finds no end of fascinating.

November 17, 2011

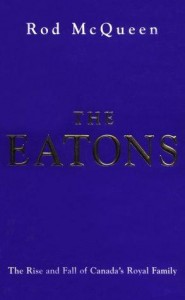

Of Eatons and Avenues

Last night I finished Rod McQueen’s The Eaton’s: The Rise and Fall of Canada’s Royal Family, which I was reading because Jonathan Bennett had included in his Power & Politics Book List, and then I found a copy in a cardboard box outside a house on Borden Street last summer. And to be reading this book right after Heather Jessup’s The Lightning Field is to be steeped in old Toronto now, to be rumbling up and down its avenues like the old cream coloured streetcars of my childhood. And to be so steeped is to be led down strange avenues online, pursuing the odd history of Dundas Street, or even leaving town to find this fascinating 1958 article in Macleans by Peter C. Newman about Deep River ON: “The Utopian town where our atomic scientists live and play has no crime, no slums, no unemployment and few mothers-in-law. But maybe you wouldn’t like it after all. Here’s why.”

Last night I finished Rod McQueen’s The Eaton’s: The Rise and Fall of Canada’s Royal Family, which I was reading because Jonathan Bennett had included in his Power & Politics Book List, and then I found a copy in a cardboard box outside a house on Borden Street last summer. And to be reading this book right after Heather Jessup’s The Lightning Field is to be steeped in old Toronto now, to be rumbling up and down its avenues like the old cream coloured streetcars of my childhood. And to be so steeped is to be led down strange avenues online, pursuing the odd history of Dundas Street, or even leaving town to find this fascinating 1958 article in Macleans by Peter C. Newman about Deep River ON: “The Utopian town where our atomic scientists live and play has no crime, no slums, no unemployment and few mothers-in-law. But maybe you wouldn’t like it after all. Here’s why.”

McQueen’s story of the Eaton family was readably rife with scandal and gossip, and good old fashioned story. Art heists, a foiled kidnapping, cuckolds, Fascists, terrorists, Rolls Royces, idiots, feuding siblings, and fallen empires– you wouldn’t know this was Canada. How the Eatons myth was divorced from its reality, and the public was so determined to keep the myth perpetuated. The book ends in 1997, when how far the Eatons would fall was still not entirely clear, and that they only fell further doesn’t undermine the story’s importance. That this book is out of print, however, to be found in curbside cardboard boxes only (though thank heaven for such distribution really) is totally ridiculous.

November 16, 2011

I am in a book!

Today I had the remarkable experience of walking into a bookstore and finding a book with my name on it. The Best Canadian Essays 2011 is out now, featuring my essay “Love is a Let-Down”, along with other essays by writers including Caroline Adderson, Mark Kingwell, Stephen Marche, David Mason and Barbara Stewart*. The Best Canadian Essays series editor is Christopher Doda, issue editor is Ibi Kaslik, and I’m so honoured that they’ve included my work in this collection. Though I must admit that part of the thrill is the idea of being in a book at all. Me! In a book! Which is more than kind of a dream come true.

Today I had the remarkable experience of walking into a bookstore and finding a book with my name on it. The Best Canadian Essays 2011 is out now, featuring my essay “Love is a Let-Down”, along with other essays by writers including Caroline Adderson, Mark Kingwell, Stephen Marche, David Mason and Barbara Stewart*. The Best Canadian Essays series editor is Christopher Doda, issue editor is Ibi Kaslik, and I’m so honoured that they’ve included my work in this collection. Though I must admit that part of the thrill is the idea of being in a book at all. Me! In a book! Which is more than kind of a dream come true.

*We published a great essay “The God Edit” by Barbara Stewart on Canadian Bookshelf this week. See also Caroline Adderson’s book list Imperfect People. And check out Susan Olding’s wonderful article on the essay form, “That Trying Genre”.

November 14, 2011

This is where we used to live.

2001/2002 was my final year at university, the year I had a back page column in the school newspaper and therefore had a platform from which to address the question of what it meant to live on a “grimy, yet potentially hip strip of Dundas St. West”, as my block had been described by the Toronto Star in a restaurant review of Musa. To live on such a strip meant kisses in doorways, I wrote, because no boy would ever let you walk home alone, it meant watching from your bedroom window as a dog devoured a skunk, and having to call the police when people started smashing car windows with implements from the community garden. I can’t remember what else I wrote in that piece, and Musa burned down two summers ago, but neither point means that year is lost. I have never gotten over it.

2001/2002 was my final year at university, the year I had a back page column in the school newspaper and therefore had a platform from which to address the question of what it meant to live on a “grimy, yet potentially hip strip of Dundas St. West”, as my block had been described by the Toronto Star in a restaurant review of Musa. To live on such a strip meant kisses in doorways, I wrote, because no boy would ever let you walk home alone, it meant watching from your bedroom window as a dog devoured a skunk, and having to call the police when people started smashing car windows with implements from the community garden. I can’t remember what else I wrote in that piece, and Musa burned down two summers ago, but neither point means that year is lost. I have never gotten over it.

Everything felt monumental that year, not because of anything specific, although it was our final year of school, and 9/11 occurred days into it, serving to make us think a lot about things we’d always before taken for granted. “That was a year,” wrote my friend Kate in a recent email, “we all made enormous leaps into adulthood even if many days it felt like we were just playing.” And of course, everybody has had those years, monumental if only for how they delivered us to here. A threshold to something finally real, but we were aware of it happening all the time, and so amazed to watch the world opening up before our eyes.

And so it felt entirely appropriate when I discovered last week that they’d turned our entire apartment into an art exhibition. (It all feels a bit Tracey Emin.) “They” being the people at Made Toronto, which now lives downstairs from where we used to live, though that storefront was a Chinese herb shop when it was ours. (It was a different time. We’d never heard of hipsters, and Musa was the only place to get brunch for blocks and blocks. David Miller wasn’t even the mayor then, and Spacing Magazine had yet to be invented.) The exhibition took place last year, designer furniture and housewares on display in a “typical Toronto apartment,” which is funny because there was nothing typical about it– for about nine months that I know of, that apartment was the centre of the universe. It’s also funny because it’s the ugliest apartment I have ever, ever seen. Aesthetically speaking (although “aesthetic” was not, in fact, a word I was aware of when I lived there), that apartment’s sole redeeming feature was the patio where I used to go to pretend to smoke cigarettes, and watch the city skyline.

Part of the reason I love my husband is because I brought him home for a visit from England in 2003 when the apartment was still inhabited by friends of mine. And they had a party to welcome me back, and so for two days, he got to know almost exactly what I was talking about when I talked about that place, about that time. I love that he was there, that brief intersection between my new life and my old one. I love that my roommates are still such dear friends, no matter that we live so far apart now. And I love that the hideous pink linoleum floors are just the same, and that we’ve come so far, they’re considered art now.

November 13, 2011

The Lightning Field by Heather Jessup

Knowing what I know now of Heather Jessup, it’s not altogether surprising that we had more than a few mutual friends. Heather Jessup is the sort who’s beloved by a lot of people, and the reason why was underlined to me the day she showed up at my door bearing a jar of pickles. Which was, sadly, only a few days before Halifax stole her away from Toronto, and though I was only just beginning to know her, I knew enough to be sorry to see her go. But it was consoling to know I had her first novel The Lightning Field to look forward to, and it’s doubly nice now that the book is read to know it forever has a place in my library.

Knowing what I know now of Heather Jessup, it’s not altogether surprising that we had more than a few mutual friends. Heather Jessup is the sort who’s beloved by a lot of people, and the reason why was underlined to me the day she showed up at my door bearing a jar of pickles. Which was, sadly, only a few days before Halifax stole her away from Toronto, and though I was only just beginning to know her, I knew enough to be sorry to see her go. But it was consoling to know I had her first novel The Lightning Field to look forward to, and it’s doubly nice now that the book is read to know it forever has a place in my library.

Partly because it’s a Gaspereau Book. Oh, just to hold one of these! And this one in particular, the dust jacket illustrated with diagrams of the Avro Arrow. Remove the dust jacket itself, and the book itself is patterned with the planes, triangles fashioned together into lines. The book’s typeface is a brand new one called Goluska (“used in advance of… commercial release”), and the note goes on to explain, “Also making brief appearances are Courier New and Adobe’s Garamond Premier Pro.” Beautiful thick paper, such considered design– a Gaspereau book is always something wonderful to behold. And to hold. Except that I always feel like I should wash my hands before I touch one, which makes picking up the books a little difficult.

But I managed to cast aside thoughts of my mucky mitts, and start reading The Lightning Field late last week, and it read as something apart, like nothing I could directly compare it to. It’s the story of a couple, Lucy and Peter Jacobs who meet at the end of WWII, and get married, because it’s what you do. And because they love each other, and because they’ve got dreams. Peter is working as an engineer with the A.V. Roe Company, working on the Avro Arrow’s wing’s, and they’ve built a brand new house on Maple Street in Malton. The children arrive, the years go by, Lucy looks around the cul-du-sac of her life, and imagines, “Is this it?”

And then one day– on the day the Arrow is revealed to the world for the very first time– on her way to the bakery to pick up a cake, Lucy is found unconscious in a field, struck by lightning, burned and comatose. The space between the couple becomes broader through the struggles of her recovery, and the damage become irrevocable when Peter’s dreams are smashed with the cancelling of the Arrow project. The years that follow fail to realign their lives, so spun out by loss of promise.

The Years is the book that this book put me in mind of, structurally speaking. Though The Lightning Field spans more than forty years, nothing is epic in its presentation. As Woolf did, rather than years, Jessup hones in on the moments, and the culimination of these moments into something that is life. And it is very much like life, the novel that she makes. The way the people talk in particular, and the moments themselves with their details– it’s as if Jessup has infused her novel with the essence of the short story in this way. And I’ve never read a historical novel that felt so contemporary, which is all in the prose, of course– Jessup’s writing is charged with energy, and vision, the whole way though.

The whole way through is not a journey without its bumps, of course, though the problems are less remarkable than its strengths. At times it felt as though these characters were so contained in themselves that it was difficult to understand who they were, which was certainly the case in their relations with one another, but as a reader, I wanted more privileged access. And the other problem, which I try to forget because the spell wasn’t otherwise broken, but I can’t– there would have been no CN Tower to see from Andy’s window as his plane departed from the city in 1971 (but then maybe I’d fixate more on this than the average person due to my background in CN Tower fiction).

However, The Lightning Field is not one of those books in which such detail makes or breaks, because the novel is constructed upon something more abstract and true than historical fact. And in this, the book succeeds, and also mesmerizes. Yes, with the detail, even (or especially?) removed from its context– all the bits about flight, and the engineering of a plane’s wing, and Toronto geography, and the music, and the orange colour of a suburban living room wall– so much that Jessup gets totally right. But truly, the effect comes of nothing of what this book is really about having to do with plot exactly, or with character. Context was never the point anyway, and not so simple in this way, the novel is almost a poem. A story of love, and family, and broken dreams, but it transcends that, and becomes about more and less at once, universal and specific, and absolutely transporting.

November 13, 2011

Our Best Book from the Library Haul: Argus by Knudsen/Wesson

So Argus, which was written by Michelle Knudsen and illustrated by Andrea Wesson, is another story of a misidentified egg, along the lines of The Odd Egg by Emily Gravett or Duck and Goose by Tad Hills. When it comes time to hatch chicks at school, poor Sally ends up with the odd one out. The egg hatches into what appears to be a dragon, and no one takes much notice, as poor Sally struggles to care for her most unruly “chick.” In the end, she learns that it’s not so bad to stand out from the crowd, but for me, the story’s chief appeal lies the narrative involving Sally’s teacher Mrs. Henshaw, who never bats an eye at the dragon in her room, even when she’s forced to leap atop desks to prevent it from eating her students. And anyone who dares to cross her is stopped with the teacher’s signature phrase, “Don’t be difficult.” And really, who can argue with that?

So Argus, which was written by Michelle Knudsen and illustrated by Andrea Wesson, is another story of a misidentified egg, along the lines of The Odd Egg by Emily Gravett or Duck and Goose by Tad Hills. When it comes time to hatch chicks at school, poor Sally ends up with the odd one out. The egg hatches into what appears to be a dragon, and no one takes much notice, as poor Sally struggles to care for her most unruly “chick.” In the end, she learns that it’s not so bad to stand out from the crowd, but for me, the story’s chief appeal lies the narrative involving Sally’s teacher Mrs. Henshaw, who never bats an eye at the dragon in her room, even when she’s forced to leap atop desks to prevent it from eating her students. And anyone who dares to cross her is stopped with the teacher’s signature phrase, “Don’t be difficult.” And really, who can argue with that?

November 12, 2011

Time passes for the curators

“As a scholar of a historical science I was accustomed to seeing the events of the past unfold before me like a parade. But I had thought of myself as a bystander, timeless. How ironic for me, the time traveller, to suddenly realize at the edge of a contemporary archeological exacavation that I was simply another event in the parade. And that time passes for curators, as well as for the things they study”. Dr. Peter L. Storck, “Passing into History”, ROM Magazine, Fall 2011 cc. Joan Didion, Blue Nights