December 5, 2011

Kalila by Rosemary Nixon

Earlier this year when I read Charlene Diehl’s memoir Out of Grief, Singing, I marvelled at the way that fiction holds writers to certain constraints, on the way we have to bend life and draw out connections to build a story. And Rosemary Nixon is aware of this in her novel Kalila, the story of a couple whose daughter is born with inexplicable complications and spends her life in an isolette in the NICU. A novel like this refuses to conform to narrative expectations; as Nixon’s protagonist Maggie tells us, “Stories are meant to lead somewhere. To rising action. Climax. Closure. And they lived Happily Ever After.” Of course, a story like Kalila’s takes on a different shape.

Earlier this year when I read Charlene Diehl’s memoir Out of Grief, Singing, I marvelled at the way that fiction holds writers to certain constraints, on the way we have to bend life and draw out connections to build a story. And Rosemary Nixon is aware of this in her novel Kalila, the story of a couple whose daughter is born with inexplicable complications and spends her life in an isolette in the NICU. A novel like this refuses to conform to narrative expectations; as Nixon’s protagonist Maggie tells us, “Stories are meant to lead somewhere. To rising action. Climax. Closure. And they lived Happily Ever After.” Of course, a story like Kalila’s takes on a different shape.

Which means that as a novel, Kalila is not immediately satisfying, that the narrative is set up in a way that puts the reader at a distance, that the approach is clinical, but this was never a story that was going to satisfy. And Nixon knows exactly what she’s doing here: if Maggie appears to be a protagonist in a trance, it’s because she is. If she and her husband Brodie appear to be disconnected from the world around them, from the experience of pregnancy and childbirth, even from the story they find themselves in the midst of, it’s because they’re meant to be. They feel like strangers in their own story, a story in which they never would have cast themselves, one so entirely different than everything they ever expected when they imagined their baby being born, and a reader’s experience is analogous.

Brodie is a high school physics teacher, and his classroom scenes are beautifully choreographed (and they reminded me of Monoceros in this respect, another Calgary book, and Nixon thanks Suzette Mayr as “my writing buddy”, which wasn’t actually a huge surprise). He keeps his mind off his wife’s pain and the plight of his tiny daughter by focusing on particles and waves, on the sound of his students’ happiness, and the strangely bending laws of the universe. And though as a scientist, he knows the way things fall apart, when he’s alone with his daughter, he resorts to fairy tale narratives, and he tells her a story of a tiny princess in a glass castle locked away.

Maggie doesn’t have the diversion of work, but rather the conspicuousness of being a mother without her baby. She struggles with her displacement as nurses and doctors assume care of her child, doctors and nurses who don’t even know what her name is. She longs to love her child in the proper way, but “it’s too late for love at first sight”, she says at one point, and she doesn’t know what to do with herself. Though she notes that the doctors and nurses don’t quite know what to do with her daughter either, whose problems are innumerable and indecipherable, and who isn’t getting any better.

The baby herself is at a remove from all of this, both literally and figuratively. In every sense, she is the unknown variable. There is a coldness to the parents’ approach to their child, a measuredness. They are wary, weary, heartbroken, and numb all at once. An actual acknowledgement of the workings of their hearts at this moment in time would cause either one to stop and break down, but breakdowns aren’t what Kalila is all about. This is a novel about going forward into the unknown, about how a new mother occupies herself at home during the day when her daughter has needles stuck into her head, and about remembering to put the dog out, to eat, to make small talk with acquaitances in the grocery store.

The novel’s restive pace shifts about 2/3 of the way through when Brodie and Maggie decide to bring their daughter home after five months in the hospital, to have the empty space in their lives finally filled. And though they don’t dare utter the word “miracle”, they’re both thinking it. But as Nixon, of course, has already told us, this rising action is never going to lead to closure, to happily ever after. This ending has always been an inevitable thing.

I’m attracted to stories like this for less than savoury reasons perhaps. There’s a voyeuristic element to it, and one with especially self-serving motives. To me, reading books like these is a way to stare down my very worst fears, to not look away for as long as I can, and imagine that somehow this staring might prepare me for all those things one can never be prepared for. Though I’m not fooling anyone, of course, let alone myself. Further, Nixon writes with a precision that doesn’t really tolerate such self-indulgence on my part. In Kalila, there is no such thing as indulgence– it’s all about the story, and the peculiar shape that lives take on when stories shift into such unimagined terrain.

December 4, 2011

On urban picture books, and concepts of home

I was holding Harriet’s hand the other day as we walked up the flight of stairs to our door when I heard her say under her little-girl breath, “four flights of stairs to family’s apartment.” I recognized it as a line from Corduroy, and asked her, “Whose apartment?” She said, “Lisa’s.” I said, “Did you know that we also live in an apartment?” She said, “No. We live at home.”

I was holding Harriet’s hand the other day as we walked up the flight of stairs to our door when I heard her say under her little-girl breath, “four flights of stairs to family’s apartment.” I recognized it as a line from Corduroy, and asked her, “Whose apartment?” She said, “Lisa’s.” I said, “Did you know that we also live in an apartment?” She said, “No. We live at home.”

I appreciate Don Freeman’s illustrations in Corduroy, probably for similar reasons black parents would have appreciated them when the book was published in the 1960s: here is a picture book that reflects the reality of my child’s life. Lisa’s is an urban world, with stairwells, department stores, laundromats and sidewalks. And it’s a world far removed from the one that I grew up in, at the end of a cul de sac, with a big backyard. I grew up in neighbourhoods where they didn’t even have sidewalks, and the only store nearby was a Beckers. The families we looked down upon were those with single-car garages, and the families who looked down on us had driveways made from interlocking brick.

Such a childhood served me well– who needs sidewalks when you can play in the street? And manicured lawns are fine and well when there are ravines to explore, and creeks to wade in, and games of Nicky Nicky Nine Doors to be won. But the choices we made for our family would be different– we want to be able to walk to our places of work, and not have to work so much, and not working so much means we don’t own a house, and not owning a house means we get to live in the apartment of our dreams in a neighbourhood close to the places where we work, and so it goes, a most unvicious cycle.

Ours not such an unusual choice, of course, and this is underlined by the so many wonderful children’s books these days depicting urban life. In fact, some of these books commodify urban life to such hipsterish effect– I’m thinking about Urban Babies Wear Black, or the various board books we own about sushi. We’re big fans of Mo Willems’ Knuffle Bunny Books, and for a long time, I would read these and wonder if Harriet’s urban life wasn’t urban enough, and were we denying her a proper childhood in a Brooklyn brownstone? And then I read an article about the time Willems has to spend photoshopping the unsavoury elements of his neighbourhood out of the books’ photographic illustrations, and came to terms with our urban life as it is.

Ours not such an unusual choice, of course, and this is underlined by the so many wonderful children’s books these days depicting urban life. In fact, some of these books commodify urban life to such hipsterish effect– I’m thinking about Urban Babies Wear Black, or the various board books we own about sushi. We’re big fans of Mo Willems’ Knuffle Bunny Books, and for a long time, I would read these and wonder if Harriet’s urban life wasn’t urban enough, and were we denying her a proper childhood in a Brooklyn brownstone? And then I read an article about the time Willems has to spend photoshopping the unsavoury elements of his neighbourhood out of the books’ photographic illustrations, and came to terms with our urban life as it is.

Urban life presented how it is is why we love Bob Graham’s Oscar’s Half Birthday, with the graffiti in its streets and the wonderful rumble of the train overhead. It’s why we love Subway by Anastasia Suen and Karen Katz (“We go down to go uptown. Down down down in the subway”). Joanne Schwartz and Matt Beam’s City Alphabet and City Numbers present city grit in all its glory. And Don Freeman’s contemporary too, Ezra Jack Keats, whose sidewalks and alleys are ways of delight. Even Shirley Hughes’ books with their domestic focus have the city as their backdrop– buses, stoops, parks and traffic.

We are fortunate that some of our very favourite urban stories are set in the city where we live: Allan Moak’s A Big City ABC, poems from Alligator Pie, Who Goes to the Park by Warabe Aska, Jonathan Cleaned Up and Then He Heard a Sound by Robert Munsch, and when Harriet’s bigger, I hope she’ll enjoy Bernice Thurman Hunter’s Booky books as much as I did. One of our favourite books of all time is Teddy Jam’s Night Cars, set against a Toronto streetscape, and we love the familiar TTC as presented in Barbara Reid’s The Subway Mouse. (Find more Toronto kids books as recommended by Imagining Toronto‘s Amy Lavender Harris.)

We are fortunate that some of our very favourite urban stories are set in the city where we live: Allan Moak’s A Big City ABC, poems from Alligator Pie, Who Goes to the Park by Warabe Aska, Jonathan Cleaned Up and Then He Heard a Sound by Robert Munsch, and when Harriet’s bigger, I hope she’ll enjoy Bernice Thurman Hunter’s Booky books as much as I did. One of our favourite books of all time is Teddy Jam’s Night Cars, set against a Toronto streetscape, and we love the familiar TTC as presented in Barbara Reid’s The Subway Mouse. (Find more Toronto kids books as recommended by Imagining Toronto‘s Amy Lavender Harris.)

The urban setting in children’s literature has become one we can almost take for granted over the past 50 years, thanks to pioneering author/illustrators like Freeman and Keats. These days, children’s books are working to further broaden notions of home in stories like Maxine Trottier’s Migrant, about a young girl belonging to a family of itinerant workers. In Laurel Croza’s award-winning I Know Here, a girl whose home is a trailer in Northern Saskatchewan contemplates a move across the country to Toronto, and takes stock of all she knows and loves about the place where she lives. Martha Stewart Conrad‘s books (we like Getting There) show children from communities all over the world enacting various versions of every day life, portraying the fascinating ways in which we’re all alike and different at once.

How wonderful that my child’s storybook worlds can be as diverse as the one we see outside our window. And once she understands that home is a concept that is broader than just this place where we live, she’ll know how hers fits in with all the rest of them.

December 2, 2011

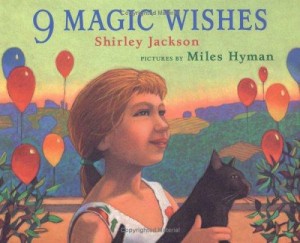

Our Best Book of the Library Haul: 9 Magic Wishes by Shirley Jackson

Harriet is amazing, and so too turn out to be the books she randomly plucks off the shelf at the library. And this week it was 9 Magic Wishes by Shirley Jackson, a book I didn’t even realize existed. This new edition is illustrated by Miles Hyman, Jackson’s grandson, who so perfectly managed to capture the essence of Shirley Jackson: the Gothic architecture of the house, the cat’s constant presence, the weirdness. But there is nothing sinister here, and the book is absolutely charming. The prose displaying Jackson’s skill with cadence and euphony. It’s the story of a strange day during which all the trees were flying balloons, and a magician came down the street granting 9 magic wishes, but what if you only want 8? (My favourite wish was “a little box, and inside was another little box and inside is another little box and inside is another little box and inside is an elephant.”)

Harriet is amazing, and so too turn out to be the books she randomly plucks off the shelf at the library. And this week it was 9 Magic Wishes by Shirley Jackson, a book I didn’t even realize existed. This new edition is illustrated by Miles Hyman, Jackson’s grandson, who so perfectly managed to capture the essence of Shirley Jackson: the Gothic architecture of the house, the cat’s constant presence, the weirdness. But there is nothing sinister here, and the book is absolutely charming. The prose displaying Jackson’s skill with cadence and euphony. It’s the story of a strange day during which all the trees were flying balloons, and a magician came down the street granting 9 magic wishes, but what if you only want 8? (My favourite wish was “a little box, and inside was another little box and inside is another little box and inside is another little box and inside is an elephant.”)

December 1, 2011

Big Town: A Novel of Africville by Stephens Gerard Malone

I read Stephens Gerard Malone’s Big Town: A Novel of Africville this week as the story of the crisis of Attawapkiskat unfolded in the media, and each story so illuminated the other. The story of a Canadian community whose people live in unheated shacks with no running water, with no access to safe drinking water. A community of people treated as second-class citizens by the rest of the world– Malone writes about how hydro lines were down, Africville was always the last place the electric company came to, and usually when you called the police, they never came at all. A community for which the outside world purports to know what’s best, applying simple solutions to complicated problems, solving exactly nothing, and never mind all that gets lost.

I read Stephens Gerard Malone’s Big Town: A Novel of Africville this week as the story of the crisis of Attawapkiskat unfolded in the media, and each story so illuminated the other. The story of a Canadian community whose people live in unheated shacks with no running water, with no access to safe drinking water. A community of people treated as second-class citizens by the rest of the world– Malone writes about how hydro lines were down, Africville was always the last place the electric company came to, and usually when you called the police, they never came at all. A community for which the outside world purports to know what’s best, applying simple solutions to complicated problems, solving exactly nothing, and never mind all that gets lost.

Africville was a black settlement outside of Halifax Nova Scotia, razed during the 1960s by the city for reasons of public health and progress. Malone situates his novel in the community’s dying days, showing that social order had broken down by this time, as it had in so many communities during that turbulent decade. Africville had become conspicuous by its proximity to the town dump, and to the unsavoury characters attracted to its fringes, like Early Okander’s father.

However, Early himself, who is white, a white simple-minded teenager devoted to his young friend Toby, is embraced by the community, and cared for by its residents all the while his father beats him and prostitutes him to his poker buddies on Saturday nights. In contrast to the trailer where Early and his father lives, Toby’s home with his grandfather Aubrey is a domestic oasis, supplied with nourishing food by neighbouring Mrs. Aada who owns the local store, and the company of other neighbours who remember a better time when the community was strong and thriving. It is as a testament to this better time that Aubrey is building a concert hall out of used bottles as a performance space for the Miss Portia White, the world famous singer who’d once lived in Africville and who, according to Aubrey, would be making a pilgrimage home now any day to help restore the community to its former glory.

The novel is meant to be told from Early’s perspective, though Malone refrains from the Faulkner-esque challenge of letting such a limited perspective wholly take over. Which makes Big Town a less challenging read, albeit one less narratively interesting. Malone plays with the ambiguity of Early’s point of view at times, but never so ambitiously, and the read between the lines is more obvious than it would like to be.

In many ways, Malone’s novel has more in common with a book like To Kill a Mockingbird, complete with its own Scout Finch in Early and Toby’s friend Chub, a girl who wants to be a boy and cuts her own hair with paper scissors. Though the story being filtered through the children’s point of view lacks the weight and nuance of To Kill a Mockingbird, however much that’s a high standard to hold any book to. The bleakness is also unrelenting– both Toby and Chub engage in self-harm, Aubrey is battling his own demons, Early’s father’s acts of violence against him are devastating; whither art thou, Atticus Finch?

Though that Malone proposes no saviour is wholly understandable, because certainly Africville never managed to be saved. And though at times I felt that the children’s perspectives were so limited as to simplify the story behind them, that story held fast my attention. Malone has made vivid a time and place thought lost to history, broadening the range of stories that we call Canadian.

November 30, 2011

The Vicious Circle reads Imagining Toronto

Last night, The Vicious Circle gathered in a the farthest reaches of the inner-city to read Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto (which was one of my favourite books of 2010). We’d braved torrential downpour to be there (which now joins a major snowstorm and a temperature of 50 degrees celsius as weather we’ve braved in order to be Vicious in 2011). Curling up in the world’s coziest living room, lined with books (as is every room in that house), and well-supplied with cheese, we sat down and gossiped, and gossiped some more, and then it was time to speak of bookish things.

Last night, The Vicious Circle gathered in a the farthest reaches of the inner-city to read Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto (which was one of my favourite books of 2010). We’d braved torrential downpour to be there (which now joins a major snowstorm and a temperature of 50 degrees celsius as weather we’ve braved in order to be Vicious in 2011). Curling up in the world’s coziest living room, lined with books (as is every room in that house), and well-supplied with cheese, we sat down and gossiped, and gossiped some more, and then it was time to speak of bookish things.

Imagining Toronto left us wanting to explore Parkdale, and wanting to read The Torontonians. We loved the way Harris acknowledges how much Toronto’s neighbourhoods are at different stages of similar narratives. We talked about Kensington, the Union Station of Toronto neighbourhoods, and how much that neighbourhood had changed– apparently Sneaky Dees used to be a Pie Shop?

We loved the sense she creates of a walk around the city, the psychogeography. Learning the history of an area like Yorkville, whose reality is different from myth– Yorkville’s heyday wasn’t a long day. We liked the structure of the book for the most part, how she organizes by neighbourhoods. We note that Toronto books were how we learned about Toronto back when we were growing up in the suburbs and small towns. As Harris writes, a city unfolds from its telling, and culture emerges from narrative. We also realize for the first time that all of us grew up in the suburbs and small towns, none of us in Toronto at all. We note that we’re part of a homogenization of the city, in the age of “the myth of the monocultural suburb.”

Some of us took issues with categorical statements that framed the city in a way that was contrary to how we understand it. That the literary Annex is not dead, for one. Or that Little Italy is not the only neighbourhood in Toronto with connections to the Old World, when we’re thinking about Roncesvalles, Little Portugal, Corso Italia, and others.

We like how the book succeeds in doing what city books are meant to do– not describing the city, but recreating the city, becoming the city. We talked about Toronto as a city without an identity, and noted that it’s not that Toronto doesn’t have a creation myth, but that it hasn’t been immortalized. We talked about the nuances of the chapter on multiculturalism, and Harris’s ideas about multiculturalism being a process that begins with us engaging with tensions, acknowledging our own discomfort with one another.We felt the “Desire Lines” chapter was less successful, and wondered about its organization– parts about gay literature, sex work, pedophilia, and birth didn’t seem to fit together so well. We expressed discomfort with gay literature belonging with the rest, and also with the lack of nuance in the bit on sex work (and wondered why it didn’t fit into the chapter on Work). We wondered why the part about Anthony De Sa’s Barnacle Love and the the Shoeshine Boy might not have fit better into a chapter on Little Portugal. Why were these stories removed from the neighbourhoods in which they took place?

Imagining Toronto, we decided, functions as a remarkable starting point, and creates desire to go explore both the city and the its stories. We praised its balance of academic and accessible writing, and it was pointed out that Harris is writing about really complex ideas in this book, but delivers them in a way that is so readable and seems unconscious of their weight. We talked about this book being published by a small Toronto press rather than an academic press, and what an undertaking this must have been for Mansfield Press, and perhaps why the overall package is intimidating to behold– small text, no images. We noted that it must have been an undertaking for Harris as well, and that nobody had ever attempted to do this. We noted that Harris does it so well that even her footnotes were interesting. We wondered about books that were missing from the book, and the Toronto stories still to come. Some of us thought we’d check out the Imagining Toronto website, and we all look forward to seeing what Harris does next (and to reading Imagining Toronto Part II).

And then we started gossiping again, and soon the cheese was nearly gone.

November 29, 2011

Frog and Toad: The Letter

Without a bit of exaggeration, I promise you that “The Letter” by Arnold Lobel is the very best short story I’ve read lately. A chapter in Lobel’s book Frog and Toad Are Friends, “The Letter” begins with Frog coming along to discover his friend Toad sitting on his porch looking sad. Toad explains that this is his sad time of day, because it’s the time of day when he waits for the mail, but not once has he ever received a letter.

Without a bit of exaggeration, I promise you that “The Letter” by Arnold Lobel is the very best short story I’ve read lately. A chapter in Lobel’s book Frog and Toad Are Friends, “The Letter” begins with Frog coming along to discover his friend Toad sitting on his porch looking sad. Toad explains that this is his sad time of day, because it’s the time of day when he waits for the mail, but not once has he ever received a letter.

Toad, characteristically, is resigned to his sadness, but Frog wants to help his friend. So he rushes home and he writes Toad a letter, arranging to have it delivered to Toad by– and wait for it– “a snail that he knew.” And I’m not going to give away any spoilers here, but I suspect you can surmise where the rest of the story might go.

Frog and Toad is a recent discovery for us, part of the Classic I Can Read Books whose series include both Frances and Little Bear, who we love. All three series are simple in their language, but magic in their depths, in their strangeness, their child’s-eye-view of the world revealing such startling vision. The characters are all lovable, real in their foibles, and driven by a very human kind of motivation (which is remarkable, actually, when we’re talking about toads, badgers, and bears).

Frog and Toad in particular is philosophy and poetry, provocative, but also comforting. And they’re funny, on the surface yes, but also underlyingly so in a way that young readers won’t necessarily understand, but won’t feel foolish for missing either. Arnold Lobel never patronizes. What a truly masterful storyteller.

November 27, 2011

True Stories: My Canada Reads Addendum

CBC Canada Reads is tackling nonfiction for 2012, which got me thinking about true stories. One of the best things about lately barrelling through my unread books in author-alpha-order is that I’ve finally been driven to pick up the nonfiction I’ve been so long putting off, fiction always being what I turn to first. And so I finally read Christopher Dewdney’s Soul of the World, biographies of Elizabeth Bowen, Gertrude Bell and The Eaton Family. Nonfiction I’ve been compelled to read without prodding recently have been Maria Meindl’s Outside the Box, the biography of Virginia Lee Burton, Bring on the Books for Everybody, and Cinderella Ate My Daughter. So yes, there has been a lot of nonfiction to appreciate.

CBC Canada Reads is tackling nonfiction for 2012, which got me thinking about true stories. One of the best things about lately barrelling through my unread books in author-alpha-order is that I’ve finally been driven to pick up the nonfiction I’ve been so long putting off, fiction always being what I turn to first. And so I finally read Christopher Dewdney’s Soul of the World, biographies of Elizabeth Bowen, Gertrude Bell and The Eaton Family. Nonfiction I’ve been compelled to read without prodding recently have been Maria Meindl’s Outside the Box, the biography of Virginia Lee Burton, Bring on the Books for Everybody, and Cinderella Ate My Daughter. So yes, there has been a lot of nonfiction to appreciate.

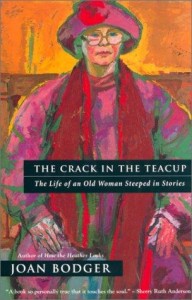

But to show my true appreciation, and in the tradition of me reading alongside and offside what CBC folks are doing, I’m going to rereading a truly great Canadian nonfiction book this winter. It’s like Canada Reads Independently, but it’s one book, and a lot less trouble. I’m going to be rereading Joan Bodger’s memoir The Crack in the Teacup: The Life of a an Old Woman Steeped in Stories, and I’d love it if you could read along with me. If you’re following along with Canada Reads, I promise that your experience will be richer if you include this book along with the other five (and that it will blow the other five out of the water, no contest.)

From my blog post about the book: “Joan Bodger’s life was never, ever boring, from the grandmother who was killed in a shipwreck, to her unconventional girlhood as the daughter of a sailor, her stint in the army working as in decoding, the terrible sadness of her family life, what she learned about story and its power to transform children’s lives (and what I learned about Where the Wild Things Are in reading about this), her fascinating work in early childhood education, the loveliness of her second marriage, her shamelessness (which is learned, and earned with age), her honestly, her passion, that she placed her husband’s ashes in the foundations of the Lillian H. Smith Library which was then under construction.”

November 27, 2011

Launch: Best Canadian Essays 2011, December 6

The Best Canadian Essays 2011 will be launching on Tuesday December 6 at the Dora Keogh Pub (Broadview and Danforth) at 7:00. I will be there and will be reading from my essay, and I’d love to see you there!

The Best Canadian Essays 2011 will be launching on Tuesday December 6 at the Dora Keogh Pub (Broadview and Danforth) at 7:00. I will be there and will be reading from my essay, and I’d love to see you there!

In other events, I’m also looking forward to hearing Rebecca Rosenblum (The Big Dream) and Anne Perdue (I’m a Registered Nurse Not a Whore) read this Thursday December 1 at the Lillian Smith Library at 6:30.

November 26, 2011

A pile of books

Today we went to a book and toy sale at Huron Playschool, where Harriet will attend next year when she is three (and “when I am a boy,” she has noted, intriguingly). The sale was to support a trust fund for the son of Jenna Morrison, who was killed in a cycling accident two weeks ago, and whose death has profoundly affected our community, even those of us who didn’t know her.

Today we went to a book and toy sale at Huron Playschool, where Harriet will attend next year when she is three (and “when I am a boy,” she has noted, intriguingly). The sale was to support a trust fund for the son of Jenna Morrison, who was killed in a cycling accident two weeks ago, and whose death has profoundly affected our community, even those of us who didn’t know her.

We got a pile of books, happy to be able to do something to help. We brought them home and began to read through the stack, which wouldn’t have made for a blog post normally, except that every single book that we read was so incredibly good. We got Silly Lilly by Agnes Rosenstiehl , Owl Babies by Martin Waddell and Patrick Benson, Paddington Takes a Bath by Michael Bond, A Difficult Day by Eugenie Fernandes, Beneath the Bridge by Hazel Hutchins and Ruth Ohi, and The Alphabet Room by Sarah Pinto.

November 24, 2011

Midsummer Night in the Workhouse and My Friend Says It's Bullet-Proof

Midsummer Night in the Workhouse is a collection of Diana Athill’s short stories from the 1950s to the 1970s, published in Britain by the fabulous Persephone Books, and now in Canada by the just as worthy House of Anansi Press. I read it this week, and just happened to follow it with Penelope Mortimer’s My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof, first published in 1967 and reissued by Virago Classics in the 1980s. The lone connection between the two, I thought, was that I’d bought another of Penelope Mortimer’s novels Daddy’s Gone a Hunting at the Persephone Shop when we were in England last winter. But then something in the tone of the Mortimer book served to be illuminating the Athill all the way through, and never was this more clear than when I came across the line, “But what? What shall I do? It will all happen. When it’s happened, you’ll know what you did. Not until then.”

Midsummer Night in the Workhouse is a collection of Diana Athill’s short stories from the 1950s to the 1970s, published in Britain by the fabulous Persephone Books, and now in Canada by the just as worthy House of Anansi Press. I read it this week, and just happened to follow it with Penelope Mortimer’s My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof, first published in 1967 and reissued by Virago Classics in the 1980s. The lone connection between the two, I thought, was that I’d bought another of Penelope Mortimer’s novels Daddy’s Gone a Hunting at the Persephone Shop when we were in England last winter. But then something in the tone of the Mortimer book served to be illuminating the Athill all the way through, and never was this more clear than when I came across the line, “But what? What shall I do? It will all happen. When it’s happened, you’ll know what you did. Not until then.”

Athill’s characters are similarly detached from their own experiences, lately set adrift in narratives beyond their control, and yet they are fascinated by the drifting, by where it’s taking them. They are aware of the growing gap between how they’re perceived by the world and who they actually are, or perhaps by how the former is shaping the latter, and their adriftness allows them to inhabit that liminal space. These are characters all on the threshold of something, and Athill holds them there, poised, right before it really happens and they find out what they’ll do.

In “The Real Thing”, a young girl attends a party and has her first kiss, viewing the entire evening as a rehearsal for something great to come, her faith in herself still wholly unshaken, and her naivete is startling, funny, and heartbreaking. In “No Laughing Matter”, a young woman is rejected by the lover in whom she’d invested so much, and is able to view herself from afar, as had the character in the first story; she begs her future self, “Whatever it may seem to you then, you must remember that now it is like this, that it couldn’t possibly be more terrible. Please, please promise that you will never laugh.”

These are characters who are trying on guises, playing at being the people they will one day become. In other stories, those who are already established in themselves are also playing at something: romances enacted by lovers aware there is no future, characters on vacation daring to become somebody else for a while, what a wife will do when her husband is away, or when she does the unexpected and storms drunkenly after an argument in the dark of night. These are characters toying with the possibilities of narrative, just as much as is the frustrated writer on retreat in the title story. And when she finally finds her inspiration, the story starts flowing, almost just out of her control, and she follows it where it leads her, which is what all these characters are doing anyway.

Some fifty years old, Athill’s stories read like they’re contemporary, as does the work of Penelope Mortimer, though this could be because so many issues that women writers were grappling with in the ’50s and ’60s are still unresolved. Or at least this seems to be the case when one considers Mortimer’s work, the frustrated suburban wife and mother in Daddy’s Gone a Hunting scheming to get her daughter an abortion, or Muriel Rowbridge in My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof who has just lost a breast to cancer and is trying come to terms with what has happened to her and her body in relation to her identity as a woman.

Some fifty years old, Athill’s stories read like they’re contemporary, as does the work of Penelope Mortimer, though this could be because so many issues that women writers were grappling with in the ’50s and ’60s are still unresolved. Or at least this seems to be the case when one considers Mortimer’s work, the frustrated suburban wife and mother in Daddy’s Gone a Hunting scheming to get her daughter an abortion, or Muriel Rowbridge in My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof who has just lost a breast to cancer and is trying come to terms with what has happened to her and her body in relation to her identity as a woman.

My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof is The Golden Notebook meets The Edible Woman. Muriel is a columnist for a woman’s magazine in England, sent to Canada with a contingent of journalists for a cultural discovery tour. She’s the only woman in her group, and this is her first foray into the world since her surgery, and also since her breakup with her married lover. She is conscious of her status in the group, but more so of the prosthetic breast tucked inside her bra. She finds herself connecting on various levels with men she encounters on the trip, and finds that her missing breast and her experience with cancer renders no connection staightforward.

As with Athill’s characters, Muriel has been removed enough from her own context that she is free to experiment in looking at herself (which is also to be being seen) in new ways. New sexual experiences and an affair with a man who’s also known tragedy gives her a sense of renewal:

“She had found, after all this time of searching, an image: myself as I am. I prefer myself as I am. The implications came crowding in on her with the impact of light, air and sound after a long imprisonment. Boldness and freedom were both available. She could do anything she wanted to do.”