December 15, 2011

Terroryaki by Jennifer K. Chung

Inside the realm of too much information, you should probably know that I spent a good hour and a bit in the bath last night enjoying Jennifer K. Chung’s novel Terroryaki. And yes, this novel was the winner of the 2010 3-Day Novel Contest, which probably explains its frenetic pacing and shamelessly surfacey plotline, but it’s also about $10 cheaper than your average paperback, its smart design compact enough to fit into your back pocket, and shameless good fun. And perhaps its just the suggestion of its cover, but I came away feeling as though I’d just read a comic book without the pictures (right down to the demon showdown at the end).

Inside the realm of too much information, you should probably know that I spent a good hour and a bit in the bath last night enjoying Jennifer K. Chung’s novel Terroryaki. And yes, this novel was the winner of the 2010 3-Day Novel Contest, which probably explains its frenetic pacing and shamelessly surfacey plotline, but it’s also about $10 cheaper than your average paperback, its smart design compact enough to fit into your back pocket, and shameless good fun. And perhaps its just the suggestion of its cover, but I came away feeling as though I’d just read a comic book without the pictures (right down to the demon showdown at the end).

Daisy’s sister’s wedding is only 3 months away, but her parents are still disapproving of her fiance for not being Asian enough, or rather for not being Asian at all. ( I enjoyed Daisy’s ever-shrieking mother, and Daisy’s description of her: “She wasn’t a Tiger Mom. She was more like a squirrel”). The family dramas are, at least, taking the heat off Daisy for her lack of drive– she works part time in a teriyaki restaurant, and is a passionless student at the community college. Certainly, Daisy does have her passions though: art and food (and food blogging). She becomes obsessed with a food truck she begins to spot around town with a skull and crossbones painted on it, and the promise, “The Best Teriyaki in Seattle.” The teriyaki is indeed delicious, but the truck has a ghostly aura. It keeps appearing and disappearing mysteriously, and it soon becomes clear that something sinister is afoot (possibly connected with Daisy’s sister’s Fascist wedding planner).

It’s rare to read a novel about a blogger, and Chung has done well in incorporating Daisy’s blog posts into the text, adding an additional layer of meaning. The other thing about Terroryaki was that it was all about food, and so evocatively so that the book left me starving, which, being in the bathtub, I could really do very little about. But apart from this complaint, I liked the book completely.

December 14, 2011

My Favourite Not-New Books of 2011

Saving Rome by Megan K. Williams: This short story collection had a mixed response when we read for my book club in October, but I devoured it, adored its depiction of expatriate life, thought Williams’ writing was fabulous, funny and surprising, and now whenever I hear Williams reporting on the CBC from Rome, there’s a whole new dimension to the broadcast.

Saving Rome by Megan K. Williams: This short story collection had a mixed response when we read for my book club in October, but I devoured it, adored its depiction of expatriate life, thought Williams’ writing was fabulous, funny and surprising, and now whenever I hear Williams reporting on the CBC from Rome, there’s a whole new dimension to the broadcast.

Virginia Lee Burton: A Life in Art: If you thought that Burton’s books were interesting, you don’t know the half of it. She was a fascinating woman, a textile designer, and her ideas about book design and children’s books are so subtly presented in her books that you’ve probably taken them for granted, but to have them illuminated makes the books so much richer. It’s a quick read, a beautiful book full of lovely images. Plus her sons have nothing but good things to say about her, which is unusual for a successful woman writer, no?

White Stone: The Alice Poems by Stephanie Bolster: Bolster won the Governor General’s Award for this book which re-examines the mythical girl Alice from every angle. I love its metafictional elements, its bookishness, cross-textual references and that it was an absolute pleasure to read.

White Stone: The Alice Poems by Stephanie Bolster: Bolster won the Governor General’s Award for this book which re-examines the mythical girl Alice from every angle. I love its metafictional elements, its bookishness, cross-textual references and that it was an absolute pleasure to read.

The 27th Kingdom by Alice Thomas Ellis: Here was the surprise of the year, this paperback which had been  languishing on my shelf forever and ever turned out blow my mind with goodness. Think Muriel Spark and Graham Green ala Travels With My Aunt, hilarious (see the bit about eating babies) and an Anglophile’s dream (see the bit about the tea). You’ve got to read it. I love the bit about the horse meat. I read most of this during a brilliant 2 hrs at Huron Washington playground sprawled in the backseat of the play jeep while Harriet put sand in a bucket and dumped it out over and over again.

languishing on my shelf forever and ever turned out blow my mind with goodness. Think Muriel Spark and Graham Green ala Travels With My Aunt, hilarious (see the bit about eating babies) and an Anglophile’s dream (see the bit about the tea). You’ve got to read it. I love the bit about the horse meat. I read most of this during a brilliant 2 hrs at Huron Washington playground sprawled in the backseat of the play jeep while Harriet put sand in a bucket and dumped it out over and over again.

All the Little Living Things by Wallace Stegner: I’ve never read Stegner before, and was afraid there might be too much rugged western manliness here, but here was a West I recognized from women authors (Sharon Butala in Lilac Moon and Joan Didion in Where I Was From) and I fell in love with the place. And with Stegner’s writing: the party scene is the best scripted party scene in the entire history of literary party scenes.

All the Little Living Things by Wallace Stegner: I’ve never read Stegner before, and was afraid there might be too much rugged western manliness here, but here was a West I recognized from women authors (Sharon Butala in Lilac Moon and Joan Didion in Where I Was From) and I fell in love with the place. And with Stegner’s writing: the party scene is the best scripted party scene in the entire history of literary party scenes.

Pathologies by Susan Olding: I hadn’t heard of Olding when we both placed second in the Edna Staebler Contest last  year, and so I didn’t understand what it meant that we were even acknowledged in the same stratosphere. And then suddenly her name started popping up in conversations everywhere, so I had to check out Pathologies, and it’s kind of the definitive book of amazing essays. She writes about troubled family relationships, infertility, her daughter’s adoption from China, and the challenges of motherhood with an admirable gutsiness, and amazing grace. She asks probing questions about and sets an inspiring example for how writers might be advised to consider the role of the self in non-fiction.

year, and so I didn’t understand what it meant that we were even acknowledged in the same stratosphere. And then suddenly her name started popping up in conversations everywhere, so I had to check out Pathologies, and it’s kind of the definitive book of amazing essays. She writes about troubled family relationships, infertility, her daughter’s adoption from China, and the challenges of motherhood with an admirable gutsiness, and amazing grace. She asks probing questions about and sets an inspiring example for how writers might be advised to consider the role of the self in non-fiction.

The Torontonians by Phyllis Brett Young: Imagine Betty Draper, but in suburban Toronto rather than Ossining NY, and armed with a buckwheat lawn instead of a shotgun. This novel anticipates Betty Friedan and Atwood’s The Edible Woman, but also invokes a Toronto of which much is now lost to us, and much has also stayed the same. This is the novel everybody wants to read once they’ve finished reading Imagining Toronto (and rightly so).

The Torontonians by Phyllis Brett Young: Imagine Betty Draper, but in suburban Toronto rather than Ossining NY, and armed with a buckwheat lawn instead of a shotgun. This novel anticipates Betty Friedan and Atwood’s The Edible Woman, but also invokes a Toronto of which much is now lost to us, and much has also stayed the same. This is the novel everybody wants to read once they’ve finished reading Imagining Toronto (and rightly so).

Elizabeth Bowen by Victoria Glendinning: Oh, the pleasure of a brilliant biography. And so few writers are really  capable of it, but Glendinning is a master. Bowen herself wasn’t even the most important reason why this book was wonderful, but this book was the reason I came away with a whole new appreciation of her work.

capable of it, but Glendinning is a master. Bowen herself wasn’t even the most important reason why this book was wonderful, but this book was the reason I came away with a whole new appreciation of her work.

A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews: I was officially the very last person on earth to read this book, and had held its hype against it, but that’s ridiculous. The book is amazing. But you already knew that.

A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews: I was officially the very last person on earth to read this book, and had held its hype against it, but that’s ridiculous. The book is amazing. But you already knew that.

December 13, 2011

My Favourite New Books of 2011

It’s been a funny old year for me reading-wise. I read fewer new books in general, and I read a lot of new books that were kind of disappointing. I enjoyed much-hyped American books like This Beautiful Life and The Submission, but found them lacking as literature in ways their NYTimes reviews never referred to. A lot of new releases never appealed to me, and all subsequent success never managed to nudge my prejudices. I read very little little poetry, and focused too much on women writers. And more than anything else, I focused on my vast collection of unread novels acquired at various used book-sales over the years, and found such treasures there once I blew the dust off. Also remarkable is that I read so many great books this year that were written by friends of mine, such as Jessica Westhead’s And Also Sharks and Rebecca Rosenblum’s The Big Dream, and though both of these are among my 2011 literary highlights, I’m aware that I’m too close to be fully objective about them.

When I review any book upon my blog, it’s because I feel that the book is worth my time and yours, and a listing of those that have risen to the top can be found here. And what follows now is the top of the top of another rewarding reading year.

Blue Nights by Joan Didion: Like everything Joan Didion writes, this book is not easily summarized and has been misunderstood, even by people who’ve read it. Though apparently it had its origins in a less personal book about parenting, it became an examination of aging and mortality for one to whom it had never occurred that such ideas could be reality. To compare this book with “Good-Bye To All That” and “On Keeping A Notebook” only underlines its depth– amazing how much about loss someone so consumed with nostalgia never knew, but that’s what age does. Like everything Joan Didion writes, the meaning comes from her articulation of universal experience intersecting with her own particular world view. Part of the attraction is pure Joan Didion allure, yes, but most of the attraction is words unloaded with such remarkable precision.

Blue Nights by Joan Didion: Like everything Joan Didion writes, this book is not easily summarized and has been misunderstood, even by people who’ve read it. Though apparently it had its origins in a less personal book about parenting, it became an examination of aging and mortality for one to whom it had never occurred that such ideas could be reality. To compare this book with “Good-Bye To All That” and “On Keeping A Notebook” only underlines its depth– amazing how much about loss someone so consumed with nostalgia never knew, but that’s what age does. Like everything Joan Didion writes, the meaning comes from her articulation of universal experience intersecting with her own particular world view. Part of the attraction is pure Joan Didion allure, yes, but most of the attraction is words unloaded with such remarkable precision.

Outside the Box by Maria Meindl: This is the book I can’t stop talking about, and I’m pleased that I’ve  managed to win it at least a few readers. As noted in a conversation with a friend today, Meindl could write about anything and it would be interesting, but her subject is so interesting too. She chronicles the history of Canadian magazine and broadcast journalism, the history of Toronto literati (and the bohemian Gerrard Street Village in the ’50s), the status of women throughout the 20th century, the dazzling enticement of celebrity, and the story of her extraordinary grandmother whose eccentricities and foibles make her a fascinating character (though undoubtedly a frustrating family relation). But most of all, it’s a really great read, and Meindl proves herself a deft handler of narrative.

managed to win it at least a few readers. As noted in a conversation with a friend today, Meindl could write about anything and it would be interesting, but her subject is so interesting too. She chronicles the history of Canadian magazine and broadcast journalism, the history of Toronto literati (and the bohemian Gerrard Street Village in the ’50s), the status of women throughout the 20th century, the dazzling enticement of celebrity, and the story of her extraordinary grandmother whose eccentricities and foibles make her a fascinating character (though undoubtedly a frustrating family relation). But most of all, it’s a really great read, and Meindl proves herself a deft handler of narrative.

The Antagonist by Lynn Coady: What I’ve only yet confessed to my closest friends is that I’ve never wanted to have sexual relations with a fictional character the way I wanted to get with Rank, Coady’s outsized narrator. My more public declaration was that this was one of the few books ever that I would have read forever and ever, the story and the voice absolutely gripping. I loved the narrative ambiguity, the metafictional elements, the humour, the spot-on portrayal of small town life and also university life (because in many ways, this is as much a campus novel as was Mean Boy). Lynn Coady is amazing, and this book is her very best yet.

The Antagonist by Lynn Coady: What I’ve only yet confessed to my closest friends is that I’ve never wanted to have sexual relations with a fictional character the way I wanted to get with Rank, Coady’s outsized narrator. My more public declaration was that this was one of the few books ever that I would have read forever and ever, the story and the voice absolutely gripping. I loved the narrative ambiguity, the metafictional elements, the humour, the spot-on portrayal of small town life and also university life (because in many ways, this is as much a campus novel as was Mean Boy). Lynn Coady is amazing, and this book is her very best yet.

This Will Be Difficult to Explain and other stories by Johanna Skibsrud: Were this the very first book we’d ever read by Skibsrud, I think she’d be the critics’ darling, and we’d all be lamenting her underappreciatedness. But her Giller win last year cast her into the spotlight with The Sentimentalists, which means that all the people who dislike successful people don’t like her and neither do those with little patience for challenging writing (and that almost makes everybody). The Sentimentalists was a divisive book, and though I liked it, I thought it was more interesting than brilliant. Her story collection This Will be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories, however, is excellent and I’m sorry that more people haven’t had the chance to fall in love with it. When I read it a second time to prepare for my interview with Skibsrud, I discovered new depths I hadn’t even detected first time around– these stories are rife with buried treasure. My Mavis Gallant comparison didn’t come from nowhere– in the Year of the Short Story, this book stands out as one of the best.

This Will Be Difficult to Explain and other stories by Johanna Skibsrud: Were this the very first book we’d ever read by Skibsrud, I think she’d be the critics’ darling, and we’d all be lamenting her underappreciatedness. But her Giller win last year cast her into the spotlight with The Sentimentalists, which means that all the people who dislike successful people don’t like her and neither do those with little patience for challenging writing (and that almost makes everybody). The Sentimentalists was a divisive book, and though I liked it, I thought it was more interesting than brilliant. Her story collection This Will be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories, however, is excellent and I’m sorry that more people haven’t had the chance to fall in love with it. When I read it a second time to prepare for my interview with Skibsrud, I discovered new depths I hadn’t even detected first time around– these stories are rife with buried treasure. My Mavis Gallant comparison didn’t come from nowhere– in the Year of the Short Story, this book stands out as one of the best.

Never Knowing by Chevy Stevens: I am such a snob that I never get to fall in love with the books that  everybody else loves because I always think they’re terrible. Which means that I never get to wrapped up in fat paperbacks about serial killers, but with Stevens, I had the chance. I’ve heard from those who read her first book that the violence was a bit gratuitous, but I think she dialled it back a bit for this one. I loved that she managed to create suspense with a character who operated like a real person rather than one who committed stupid though plot-enabling conventions such as keeping secrets, and going down to the basement. In a truly remarkable cliche-defying feat, Steven proves that popular fiction is capable of being awesome.

everybody else loves because I always think they’re terrible. Which means that I never get to wrapped up in fat paperbacks about serial killers, but with Stevens, I had the chance. I’ve heard from those who read her first book that the violence was a bit gratuitous, but I think she dialled it back a bit for this one. I loved that she managed to create suspense with a character who operated like a real person rather than one who committed stupid though plot-enabling conventions such as keeping secrets, and going down to the basement. In a truly remarkable cliche-defying feat, Steven proves that popular fiction is capable of being awesome.

I’m a Registered Nurse Not a Whore by Anne Perdue: Oh, the gasps, as I read this book on my summer vacation. My husband had to tell me to shut up because I was bothering him, but I couldn’t stop, because Perdue kept delivering one shock after another. The range of stories in the collection is really remarkable, the spectrum including a rooming house resident to one master of the suburban barbecue (and oh, that ending. Gasp. Holy John Cheever). Perdue is Jessica Westhead meets Alexander MacLeod, and I love this book.

I’m a Registered Nurse Not a Whore by Anne Perdue: Oh, the gasps, as I read this book on my summer vacation. My husband had to tell me to shut up because I was bothering him, but I couldn’t stop, because Perdue kept delivering one shock after another. The range of stories in the collection is really remarkable, the spectrum including a rooming house resident to one master of the suburban barbecue (and oh, that ending. Gasp. Holy John Cheever). Perdue is Jessica Westhead meets Alexander MacLeod, and I love this book.

The Forgotten Waltz by Anne Enright: I don’t know if I’ll ever understand why this book never made the  awards lists this year, and maybe it’s like Skibsrud and that you get lost in the shuffle when the follow-up to your divisive acclaimed work is even better than what came before. But there is no better novel for 2011 than this one (which I read in its entirety one day in June when I was sick in bed, and it’s the only book I’ve ever read while sick that I don’t feel sick when I think about). It’s about the economic crisis for goodness sakes, and real estate boom and bust, and so this is serious stuff, you know. But it’s also about a love affair, which is the most real thing in the entire world. Enright’s sentences are to die for, but she’s also created an unforgettable voice in Gina, and perfect document of the way we live now.

awards lists this year, and maybe it’s like Skibsrud and that you get lost in the shuffle when the follow-up to your divisive acclaimed work is even better than what came before. But there is no better novel for 2011 than this one (which I read in its entirety one day in June when I was sick in bed, and it’s the only book I’ve ever read while sick that I don’t feel sick when I think about). It’s about the economic crisis for goodness sakes, and real estate boom and bust, and so this is serious stuff, you know. But it’s also about a love affair, which is the most real thing in the entire world. Enright’s sentences are to die for, but she’s also created an unforgettable voice in Gina, and perfect document of the way we live now.

Better Living Through Plastic Explosives by Zsuzsi Gartner: Zsuszi Gartner’s success is what happens when great innovative writing is marketed to the mainstream, rather than relegated to a weird literary ghetto.I read its title story first in an issue of The New Quarterly, and I’d never encountered anything else like it. And there is justice in the world in that Gartner made it to the Giller shortlist, because this collection is everything you never imagined that CanLit could be– sharp-witted, biting, urban, satirical, scathing and shocking. It asks more of its reader than the average acclaimed book tends to, but the rewards are plenty. You’ll finish this book and look around you and think, “Truly, this is a place where something is going on.” (Runner up in this category is Carolyn Black’s collection The Odious Child.)

Better Living Through Plastic Explosives by Zsuzsi Gartner: Zsuszi Gartner’s success is what happens when great innovative writing is marketed to the mainstream, rather than relegated to a weird literary ghetto.I read its title story first in an issue of The New Quarterly, and I’d never encountered anything else like it. And there is justice in the world in that Gartner made it to the Giller shortlist, because this collection is everything you never imagined that CanLit could be– sharp-witted, biting, urban, satirical, scathing and shocking. It asks more of its reader than the average acclaimed book tends to, but the rewards are plenty. You’ll finish this book and look around you and think, “Truly, this is a place where something is going on.” (Runner up in this category is Carolyn Black’s collection The Odious Child.)

And Me Among Them by Kristen den Hartog: Odd, the second book on my list about an outsized  narrator, this time Ruth Brennan who is seven feet tall and whose perspective beholds remarkable things. From the intro to my interview with Kristen den Hartog: “When I fell in love with And Me Among Them last spring, it really felt like a spring, because it was the first novel I’d loved in ages after a long cold winter. The magical elements of the story about a girl who grows to be seven feet tall and is blessed with a strange omniscience were so perfectly countered with a realism that kept the story’s feet on the ground, and the entire effect delighted me, which is remarkable when one notes my aversion to books about freakish sorts (confession: I am of the handful of people who hated Geek Love).”

narrator, this time Ruth Brennan who is seven feet tall and whose perspective beholds remarkable things. From the intro to my interview with Kristen den Hartog: “When I fell in love with And Me Among Them last spring, it really felt like a spring, because it was the first novel I’d loved in ages after a long cold winter. The magical elements of the story about a girl who grows to be seven feet tall and is blessed with a strange omniscience were so perfectly countered with a realism that kept the story’s feet on the ground, and the entire effect delighted me, which is remarkable when one notes my aversion to books about freakish sorts (confession: I am of the handful of people who hated Geek Love).”

![]() Out of Grief, Singing by Charlene Diehl: On New Years Eve last year, the Globe and Mail published recommendations by Canadian literary types, and this was Alison Pick’s. Part of my attraction to this book is my insistence upon staring worst fears in the face, which is a faulty insurance, I know, but Diehl’s story about the loss of her baby not long after birth is also an affirming tribute to the power of story, and represents a remarkable broadening of the motherhood narrative.

Out of Grief, Singing by Charlene Diehl: On New Years Eve last year, the Globe and Mail published recommendations by Canadian literary types, and this was Alison Pick’s. Part of my attraction to this book is my insistence upon staring worst fears in the face, which is a faulty insurance, I know, but Diehl’s story about the loss of her baby not long after birth is also an affirming tribute to the power of story, and represents a remarkable broadening of the motherhood narrative.

Also: A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan and Burley Cross Postbox Theft by Nicola Barker: I read these books whilst on vacations, therefore leisurely, and never put coherent thoughts together about them except I LOVE THESE BOOKS. Further, this was a year with Margaret Drabble in it, with her remarkable collected stories A Day in the Life of the Smiling Woman. So naturally, it was a very good year.

Coming tomorrow: My Favourite Not -New Books of 2011

December 12, 2011

Mnemonic: A Book of Trees by Theresa Kishkan

“And how many people could write so interestingly about filbert catkins?” asks Theresa Kishkin in her essay collection Mnemonic: A Book of Trees, and it’s a very interesting question, made no less interesting by my not knowing my catkins from my filberts anyway. Which is to say that there is a gap between Theresa Kishkan’s world and mine, between Theresa Kishkan’s brain and mine. This is a woman who keeps the bone of her dead dog’s pelvis on her desk; she writes, “This is not as macabre as it sounds (or maybe it is).”

“And how many people could write so interestingly about filbert catkins?” asks Theresa Kishkin in her essay collection Mnemonic: A Book of Trees, and it’s a very interesting question, made no less interesting by my not knowing my catkins from my filberts anyway. Which is to say that there is a gap between Theresa Kishkan’s world and mine, between Theresa Kishkan’s brain and mine. This is a woman who keeps the bone of her dead dog’s pelvis on her desk; she writes, “This is not as macabre as it sounds (or maybe it is).”

Kishkan’s essays are very different from others I’ve delighted in during the past year, Kyran Pittman’s, Susan Olding’s, Ray Robertson’s, even Joan Didion’s, all of whom write essays whose points of access were profound moments of identification with my own experience, whose prose illuminated my own experience. But Theresa Kishkan’s essays have nothing to do with my own experience, or when they do, identification is far from the point. Her essays are the epitome of what Susan Olding described in her own esssay, “That Trying Genre”:

Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.

Though the essays in Mnemonic: A Book of Trees are less unsettling than enchanting, and they’ve been echoing in my head in the days since I’ve finished reading, as I encountered the woodsy picture book Singing Away the Dark on Friday, and as my house was filled with the scent of balsam fir when we fetched our Christmas tree on Saturday. I may not live in the woods on the edge of the continent, but clearly I know something of trees- how could I not when this is the view from my bed?

And then Theresa sent me her Canadian Bookshelf reading list, and Singing Away the Dark was actually on it, and so maybe the gap between us is not so wide after all.

Whatever I know about trees though, I’ve got nothing on Kishkan who built her own house from felled logs, is an ever-avid student of dendrology, who wove a bowl from pine needles, remembers reading Nancy Drew under oaks when she was ten, who makes her home in the tree-rich province of British Columbia, spent a season inhaling the scent of Greek olive groves, and connects the beech tree to the homeland of the grandfather she barely knew. Trees are what bind this collection together, however loosely, as Kishkan shares stories from her life, the places she has been, the books she’s read, the music she’s loved, and the people she has known. She uses various trees as mnemonic devices to awaken the past and illuminate the present.

Not since I first read Pilgrim at Tinker Creek have I encountered anything like this, any mind like this. These essays are challenging, rich and surprising, and well worth the close attention they demand from their reader. And lack of knowledge of about filbert catkins ceases to matter anyway, though Kishkan leaves you curious, but the point is to follow where she leads, her path through the woods, and there’s no doubt you’re in the hands of a most capable guide.

December 12, 2011

A Jolly Old Elf

…and of course I’m talking about Abe the Advent Book Elf, who is facilitating passionate recommendations of new books every single day over at the Advent Book Blog. Check out my recommendation for Maria Meindl’s Outside the Box, which was one of my favourite books of the year. And then grow your Christmas list even longer by checking out all the others, and perhaps you might even submit a recommendation of your own!

…and of course I’m talking about Abe the Advent Book Elf, who is facilitating passionate recommendations of new books every single day over at the Advent Book Blog. Check out my recommendation for Maria Meindl’s Outside the Box, which was one of my favourite books of the year. And then grow your Christmas list even longer by checking out all the others, and perhaps you might even submit a recommendation of your own!

December 12, 2011

Speaking of Seth

Speaking of Seth, the latest issue of Canadian Notes & Queries arrived in my mailbox on Friday. It contains my essay “The Not-So-Good Terrorist: Reading Zsuzsi Gartner’s ‘Better Living Through Plastic Explosives'” which I am very proud of, about a story that I love. I’d recommend you pick up the issue when you come across it on news-stands in the coming weeks.

Speaking of Seth, the latest issue of Canadian Notes & Queries arrived in my mailbox on Friday. It contains my essay “The Not-So-Good Terrorist: Reading Zsuzsi Gartner’s ‘Better Living Through Plastic Explosives'” which I am very proud of, about a story that I love. I’d recommend you pick up the issue when you come across it on news-stands in the coming weeks.

December 11, 2011

Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Kristen den Hartog

When I fell in love with Kristen den Hartog’s novel And Me Among Them last spring, it really felt like a spring, because it was the first novel I’d loved in ages after a long cold winter. The magical elements of her story about a girl who grows to be seven feet tall and is blessed with a strange omniscience were so perfectly countered with a realism that kept the story’s feet on the ground, and the entire effect delighted me, which is remarkable when one notes my aversion to books about freakish sorts (confession: I am of the handful of people who hated Geek Love).

When I fell in love with Kristen den Hartog’s novel And Me Among Them last spring, it really felt like a spring, because it was the first novel I’d loved in ages after a long cold winter. The magical elements of her story about a girl who grows to be seven feet tall and is blessed with a strange omniscience were so perfectly countered with a realism that kept the story’s feet on the ground, and the entire effect delighted me, which is remarkable when one notes my aversion to books about freakish sorts (confession: I am of the handful of people who hated Geek Love).

But it’s because den Hartog’s novel is not about freakishness at all that the story so resonated; instead of staring at the giant girl, we’re given the gift of the world through her eyes, and the view is extraordinary. And the novel is so rich that when I finished it, I wanted to know more.

One Thursday morning in mid-November, Kristen den Hartog came over to my house for some conversation, cheese and baked goods. We tried not to be distracted by the toddler in our midst who decimated the cheese plate and sang made-up songs. What follows is an edited version of our talk, the toddler-centric bits edited out completely (and you probably won’t even notice that at one point here, I was in the other room changing a diaper).

Kristen den Hartog is a novelist, memoir writer, mom, sister, wife, daughter and incredible kids’ book blogger. And Me Among Them is due out soon in the U.S. as The Girl Giant. Her previous novels are Water Wings, The Perpetual Ending, and Origin of Haloes. The Occupied Garden: A Family Memoir of War-torn Holland, was written with her sister, Tracy Kasaboski, and they are now at work on another collaboration. She lives in Toronto with her husband, visual artist Jeff Winch, and their daughter.

I: Where did And Me Among Them begin?

I: Where did And Me Among Them begin?

Kdh: At first it was a short story about parents whose son is a giant and dies of complications from his condition. Much of that early draft focused on their loss and how they tried to get over it. Then I decided I wanted the boy to be a girl, because it presented more complicated body issues. It isn’t easy to be a teenage girl, even with a normal sized body, so I was interested in exploring that, and the more I did it, the more I realized I couldn’t have her die. I didn’t want her to be a victim. I wanted her to be powerful and strong, which is why I told the story as if she was looking down on her life from above, seeing things she couldn’t possibly see. I kept thinking, I know it can’t be that way, but I’m just going to plow through and do it because it feels right. I’m so glad I persisted, because that unusual perspective seems to me the very core of the novel.

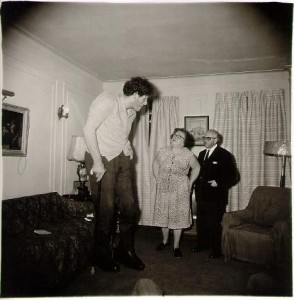

I: I’m also interested in the Diane Arbus photo Jewish Giant at Home With His Parents in the Bronx,  which you mention in your acknowledgements. How did that factor into your creation of Ruth?

which you mention in your acknowledgements. How did that factor into your creation of Ruth?

KD: I’ve known about that photo for a long time. What I love about it is how ordinary the background is and how ordinary the parents are, but he’s just rising up and changing everything by being there.

The image inspired me because of the sheer size of the boy in relation to his parents. But also I thought, when our daughter Nellie was born, in a way her presence was like that too. She was this massive force. Even though she was a normal-sized child, everything changes when you have a baby.

I: The novel literalizes so many things that I’ve only ever seen in metaphor—I’m thinking of “bird’s eye view”, “head in the clouds”, even the image of a child’s fumbling fingers playing with a dollhouse, sentences like, “After she arrived, the roof of our house came off.” It occupies this strange space between awake and dreaming, between plausible and otherwise, between metaphor and concrete. And it’s kind of a constraint to be writing in a space like that. Or did you think so?

KD: It just came really naturally. It felt like the right way to tell the story. I knew that because I was writing about an actual medical condition, there were things I needed to get right, like how it feels to inhabit a body like that, to hold a pencil, or to walk down stairs when your feet are so huge; and what can be done medically for such a person. But there had to be this playful, magical quality too, so the reader could embrace the idea of Ruth telling the story from above, and watch with her as her life unfolds.

I ended up reading other accounts like that written by people who knew a giant. So that’s how I got to understand what it’s like to be in a body like that, because they’d talk about the size of the hands and the difficulty of walking down stairs.

I: Did you come across any accounts written by giants themselves?

KdH: I came across some interviews with a woman called Sandy Allen who just died recently, actually, and her life story was very useful to me because she was born around the same time as Ruth. But mostly I read accounts by people writing about a brother or an uncle.

I: Which makes sense, actually, considering how much your story is about the family dynamics. Which was part of the reason it reminded me of a Carol Shields book, how you illuminate the ordinary in the same way she does. Your book is rife with allusions to children’s books, and the stories about giants you mentioned, but I wonder if it has any less overt antecedents?

KdH: I tend to stay away from things that feel too familiar to the project I’m working on. So for instance, when I was writing Water Wings, I read a lot about bugs and butterflies, gathering the facts I needed to create my characters’ world. This time it was the fact side of being a giant that I was looking for, and also the details I could mine from fairy-tales. I didn’t want to read novels about close family relationships and the connections between people. Those things needed to come from inside me or be the sparks I notice in my daily life.

But also, books creep in. There’s a book I read with Nellie, Sylvester and the Magic Pebble by William Stieg. It’s about a donkey named Sylvester who has a magic pebble and wishes himself into a rock because a lion is nearby. And he can’t wish his way out again, so he’s gone missing and his donkey parents are terrified and can’t find him anywhere.

It’s a heartbreaking story to read to a child, because every parent has had those terrifying thoughts. So those kinds of books are always in my head, since they explore what I write about as well—family, relationships, and the things that pull us together, as well as the things that threaten to pull us apart.

I: How has reading with your daughter and a focus on children’s books changed you as a reader and as a writer?

KdH: It’s been amazing to either rediscover or find new stories with her. It’s such a moving thing. And blogging about what we read together is wonderful because it means the stories stay with me longer. I have to put my thoughts about them into words, so I appreciate them more. As with a book club. When you sit and discuss a book with others, you get so much more out of it. I: What’s different about reading with kids too is that as an adult, you don’t very often read with people. But as a family, we’ve found ourselves talking about characters in books as a kind of shorthand, connected with ordinary life.

KdH: We’ve just gone through the whole Harry Potter series, which had us all three reading together. We got up in the morning and read at the breakfast table and then as soon as we were all together again, we would read. And in fact, that has stuck with us, because we did it so regularly with those books. The first thing Nellie says when she gets up is, “Don’t forget the book, Mom!”

I: Something else that interests me, because you talk about things creeping into books, is that I found that in your book, the outside world didn’t appear to creep in so often. There were a couple of references to songs on the radio, but we never know the song. The one exception to this is when Iris says that “women have finally had enough and they’re beginning to fight back,” and I guess this is around 1960. But otherwise, we don’t get a sense of the popular culture, and I wondered if that was a deliberate omission and what role did it play?

KdH: I wanted to keep specific reference pulls you out of that, and makes you flip to your own experience.

I: And also makes you measure the plausibility of what’s going on.

KdH: It pulls the reader up off the page, I think. It can be very effective, but in this story, I felt their world needed to be contained, closed off like the parents were as people, and that certain things needed to be blurred.

I: Which is unusual with writers writing about that time because the popular culture is such an easy reference point.

KdH: Yes. But to be honest I’m usually put off by that as a reader.

I: But there was one way the world did creep in. I reread this book around Remembrance Day, and what I noticed that I hadn’t the first time is that it’s such a war novel. It’s a domestic novel, so much about motherhood, but war is always in the background. And one of Elpeth’s aunts makes the point that “the world needs war”. Did your novel need war as well?

I: But there was one way the world did creep in. I reread this book around Remembrance Day, and what I noticed that I hadn’t the first time is that it’s such a war novel. It’s a domestic novel, so much about motherhood, but war is always in the background. And one of Elpeth’s aunts makes the point that “the world needs war”. Did your novel need war as well?

KdH: I think so, though that happened organically. Before this book, I had been writing The Occupied Garden with my sister so we were steeped in war research for a long time. It took me ages to move on to a new project because the work on that book had affected me so deeply. And when I finally did, I made Ruth’s mom an English warbride and her father a soldier, because it fit with the era I had chosen. At the time, it wasn’t something I thought about a lot. Then as the story progressed and I began to focus on making Ruth powerful and not a victim, I wanted to underscore the fact that James and Elspeth had brought their own baggage into their relationship from separate places. The problems didn’t all come from Ruth and the difficulty of having a misfit child. The more James and Elspeth fail to talk about their pasts and how the war affected them, the greater the distance grows between them. I love that point in the book where James is trying to decide whether or not to tell Elspeth about his affair with Iris. He absolutely wants to do the right thing, and he decides that his confession needs to be about his experience on the beach at Dieppe that day rather than about his infidelity. His guilt and despair about that day is what’s always been in the way of them growing closer. And Elspeth has her own confession in that sense too.

I: It’s interesting because the way that so many writers deal with the 1950s and 1960s and their focus on popular culture gives the illusion that the war was really far away by that point. I guess that’s what people were trying to do, to get on with things, but it really was so close, and your book shows that.

KdH: The children who were born in that time were born into this new world, and yet their parents had experienced all that tragedy and didn’t know how to talk about it.

I: But even if they didn’t talk about it, it was there.

KdH: And that was something that I went back and refined so that it was mentioned consistently, because I realized how much the war had really become part of the story.

I: But motherhood is also part of the story. You write about it so brilliantly. In fact, the first piece I ever read by you was “Draw Crying” in The New Quarterly.

KdH: Which was written when Nellie was Harriet’s age.

I: And Harriet wasn’t even born. I was pregnant. I remember being so struck by the piece. And then rereading it again later and realizing I didn’t even get it the first time.

KdH: Because you can’t, right? Until you go through it yourself.

I: Which you write about in And Me Among Them. That excerpt from when the baby was born—the feeding, the crying. It’s such a small part of the novel, just a paragraph. And if I hadn’t have experienced it, I might have just skipped over that part and not realized the weight of it.

KdH: I’ve always written about families. I never set out to create a body of work about families and relationships but I can see how that’s become a constant thread that runs through my work. And in the beginning, I was often taking the child’s point of view. It’s a really natural place for me to go. Even though I can’t really remember a lot of my childhood very clearly, I remember the feeling so I can write about that very effectively and I enjoy doing it.

But what’s newer to me, and what started to come after I had Nellie, was writing about the parents’ point of view in contrast to the  child’s. And I just love that. I think I began to really get it when I was working on The Occupied Garden. The book is about my dad’s family in Holland in WW2, and there’s a point in the story when a bomb landed in my dad’s backyard. He and his brother were outside playing, and they were both very badly wounded—my dad lost his leg and my uncle lost his arm.

child’s. And I just love that. I think I began to really get it when I was working on The Occupied Garden. The book is about my dad’s family in Holland in WW2, and there’s a point in the story when a bomb landed in my dad’s backyard. He and his brother were outside playing, and they were both very badly wounded—my dad lost his leg and my uncle lost his arm.

My grandfather at that time was inside the house and had heard the plane coming. He didn’t have time to run out and he called out the window to them to run, but of course it was too late, and I remember collecting the information for the book and asking my dad about that day, which he’d always downplayed as being no big deal. But this time I asked him, “What do you think it would have felt like for you were in Opa’s place? If you were inside the house and you were the father and you were calling to us and there was a plane coming?” And when he wrote back, he said, “I can’t believe this. I’m sitting here with tears running down my face because I’ve never thought of it that way. I always thought about it from my perspective, never my dad’s.”

And hopefully I would have thought of asking him that question even if I’d never had Nellie, because as a good writer you should be able to imagine all kinds of things without having to live through it—

I: Like how you imagined being 7 feet tall.

KdH: Yeah, but it does sort of open things up once you’re actually living it, once you’re actually being a parent.

I: In a way, all the characters in the novel are set apart from one another, and yet, you have so firmly demonstrated that we’re not so far apart in that you’ve imagined what it’s like to Ruth. You’ve allowed us to understand it. There’s such connection there. I mean, at one point, very briefly, you write from the point of view of a strawberry. You show that we really can cross these lines.

KdH: It’s the connections that are really important to me. The connections between people and the natural world around them are more important to me than the story. The connections are the story. And some people love that and totally get that, and some people want something more straightforward. But I can’t do it any other way. I can only do it my way.

I: At some point in the book, you write about giants needing to be seen to be believed. I think it’s in regards to a book that Elspeth was reading about giants. But you managed to show us Ruth without us having to see her. And you make what she sees even more important than how she looks. Was that always the more interesting question to you?

KdH: Yes. I was interested in how she saw her parents, and people like Suzy and Patrick too, and those descriptions of their dusty, sandy, sun-kissed look; when she looks down at Suzy’s part line with the bug bites. When we do see Ruth, it’s because she’s imagining what Suzy sees, and then she decides that she doesn’t want to spoil the moment of her imagining by seeing herself that way, and she puts the cloth over her mirror. It was more important for me to imagine inhabiting her body than to imagine looking at her. If we saw her too much from the outside, there would be too much distance while reading her story. I wanted to get across her sense of compassion, and empathy, and how she’s so set apart from people but able to understand them in a lovely way, even if they can’t return the gesture.

I: She’s a curiously unreliable narrator though. I love it when she talks about how the story is “her truth”, if not the truth.

KdH: Whenever anybody tells a story, it’s their version. That’s one thing my sister and I learned while working on The Occupied Garden, and interviewing my dad and his siblings about their lives. They would often tell contradicting stories. For instance, in the story about my dad and my uncle being outside when the bomb dropped, one version says that my youngest uncle (who was a baby) was asleep in his crib and didn’t wake up until after it was all over, but he remembers walking through the house and crunching over the broken glass, and coming down and seeing what had happened. It’s just a flicker of a memory and he doesn’t know if it’s real or something he created from the facts he got later. That was one of the most gratifying things about writing nonfiction – figuring out how to incorporate the various versions, and still tell a “true” story.

I: As a writer, does fiction or nonfiction feel like the more natural fit for you?

KdH: Fiction still feels more natural, because it’s more familiar; it’s what I’ve done for so long. But I like the constraints of nonfiction. It’s kind of like cooking, when you say, I can’t go out and buy anything, I have to use what’s here, and I have to make something really delicious. That to me is like nonfiction, and fiction is when you can go out and get whatever you want. It’s up to you, it’s a blank slate.

I: But sometimes a blank slate can be as intimidating as a stocked pantry.

KdH: So true.

I: Who are some of your favourite writers?

KdH: I think I answer this question differently every time it’s asked. Today, Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Carson McCullers come to mind. For children, Roald Dahl and William Steig.

I: What one book would you recommend that your readers read, in addition to your own?

KdH: Do you mean in conjunction with? That would be an interesting question to flip to readers. Two friends told me they read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn after reading my book, and loved the fit. What comes to mind for me is Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. I’m stunned to think she was only 23 when she wrote that book.

I: Who were the writers who made you want to write?

KdH: Hmm. I wanted to write before I could read. Then as an older child, I was as curious about L.M. Montgomery as I was about Anne. I was well into my 20s when I finally figured out what I wanted to write about. I suppose Alice Munro had a hand in that, because she wrote about characters and places that were familiar to me.

I: What are you reading right now?

KdH: Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol.

December 8, 2011

Virginia Lee Burton and the Graphic Novel

I’ve enjoyed Virginia Lee Burton’s books for as long as I can remember, though never more than I have in the past year as I’ve come to understand her approach to book design (and how far-reaching was her influence). Anyway, last weekend our friend Aaron picked our copy of Katy and the Big Snow, which has no dust cover because Harriet has declared it her mission to rid books the world over of their dust jackets (plus the jacket was already battered– this was a discarded library book we bought for a quarter. Jacket has been put away to avoid further battering).

I’ve enjoyed Virginia Lee Burton’s books for as long as I can remember, though never more than I have in the past year as I’ve come to understand her approach to book design (and how far-reaching was her influence). Anyway, last weekend our friend Aaron picked our copy of Katy and the Big Snow, which has no dust cover because Harriet has declared it her mission to rid books the world over of their dust jackets (plus the jacket was already battered– this was a discarded library book we bought for a quarter. Jacket has been put away to avoid further battering).

And Aaron said, “Don’t you think this looks like something by Seth?” And we thought,  “Hey, he’s right,” of course. And because I know very little about Seth or about cartooning, I did a bit of googling, and found this blog post from Drawn & Quarterly entitled “Virgina Lee Burton: Godmother of the Graphic Novel.” So goes the post:

“Hey, he’s right,” of course. And because I know very little about Seth or about cartooning, I did a bit of googling, and found this blog post from Drawn & Quarterly entitled “Virgina Lee Burton: Godmother of the Graphic Novel.” So goes the post:

I always find it curious when people draw distinctions between kids comics and kids picture books, basically you’re telling stories with pictures in both instances, and the art can’t be separated from the words. Why is Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams a comic, while Chicken and Cat is not? And really, aren’t graphic novels just pictures books for adults. Semantics, I know.

The post is referring to a slide show with the “Godmother of the Graphic Novel” title presented by cartoonist James Sturm. The site it was published on seems no longer current, and the slideshow itself isn’t functional, which is driving me crazy, because I want to see it so badly! I’ve scoured the internet for Sturm’s contact info, but no dice. So I’m disappointed, but also excited that the importance of Virginia Lee Burton might be greater than I’ve imagined yet.

December 7, 2011

On being in a book (!)

In 2007, my friend Rebecca Rosenblum had her story “Chilly Girl” published in the Journey Prize Stories 19. And I will never forget how exciting it was to go into the Book City at Yonge and Charles (which is, like many other bookstores, no longer with us) and her buy her book off the shelf. Rebecca’s first story collection came out the following year, and the whole thing was so exciting, but to me, nothing ever topped the excitement of that first actual book with Rebecca’s story in it.

In 2007, my friend Rebecca Rosenblum had her story “Chilly Girl” published in the Journey Prize Stories 19. And I will never forget how exciting it was to go into the Book City at Yonge and Charles (which is, like many other bookstores, no longer with us) and her buy her book off the shelf. Rebecca’s first story collection came out the following year, and the whole thing was so exciting, but to me, nothing ever topped the excitement of that first actual book with Rebecca’s story in it.

I also remember that a bird shat on my hand as I was walking down Charles Street toward the bookstore, and the good luck that I was wearing a mitten at the time, and I remember thinking as I contemplated good luck, “One day, I want to be in a book like that one, with binding, and editors, and everything.”

Last night, a crowd of some of the very best people I know came out to the launch of Best Canadian Essays 2011, and I proceeded to have 2 pints of beer and fall even more in love with everyone. (I had to stop at 2. At 3 pints, I get feisty and start offending people even more than usual.) It was really, truly a spectacular night, and I felt honoured that my essay was chosen, that it was published along with so many other wonderful pieces, and that so many faces in the crowd belonged to people I love as I read from “Love is a Let-Down.”

I’ve got a sense of proportion about these things. I know the pond is big and I am small, but I’m still in awe of the fact that I get to swim in it. And I really would like to publish a book of my own one day, but who among us doesn’t have a dream like that? In the meantime though, I’m feeling a tremendous amount of satisfaction about an accomplishment that bird-shit on my mitten may have portended years ago: I am in a book. And more over, it’s a pretty great book.

I’ve been revelling in every bit of all this, and it feels as wonderful as I imagined it would be.

December 6, 2011

What I Hate About Book Bloggers

It’s certainly not a secret that publishers send me books to review. I’m currently indulging in a Goose Lane binge because of a package that arrived on by doorstep last week. Most of the new releases I review have come my way via my mailbox. But I don’t make a note in each post of where my books came from, because I promise you that it really has no bearing on how that book gets reviewed. Also because professional book reviewers are not required to disclose that they were also sent the book for free, so why should I have to? I don’t regard the books I receive in the post as compensation– books don’t pay the rent, my friend. I’m not obliged to do anything with the books that come my way, to review positively, or even to review at all. Regardless of how these books found their way to me, I am beholden to nobody.

Which is not to say that this has always been the case. Of course, I’ve never received compensation for a review on my site– that’s so not my style, plus the very best books don’t have to pay people to like them. But when I started receiving books from publishers about 5 years ago, I found the whole process pretty overwhelming. I was flattered by the attention, and anxious to please, and though I was never dishonest in my early reviews, I was sometimes more generous in my assessments than I should have been. Though I also think I was a more generous reader then– 5 years of reading so many middling books does tend to make a reader rather crabby. But I’ve also found my footing as a reader, as a critic (though it’s still evolving; it has to be), I’ve read so much more, and learned so much more that I feel more comfortable to simply term a book a disaster, rather than trying to puzzle through the writer’s intentions as I might have done once upon a time. Though I don’t often declare a book a disaster here on my site, partly because it’s inconsistent with the tone here, and also because I don’t have enough free time to devote to writing reviews of books that are terrible.

During the past week, book bloggers have been getting some attention after many received a letter from William Morrow laying down the laws of book bloggerdom– reviews must be posted within a month of the book’s release, failure to adhere to these rules will result in getting bumped off their mailing list. To be honest, I didn’t find the letter or its tone too surprising– since the economy broke in 2008, I’ve noticed a similar reining in of bloggers by the big publishers I deal with. Gone are the days when they’d send me any/every book in the catalogue (and sometimes screw up the ordering so I’d end up receiving the same books twice, or three times). And obviously, I’m not exactly heartbroken about this, because the three-book thing never really seemed like an excellent business plan anyway. Also because there were so many books that I was often overwhelmed, and I ended up reading books I wasn’t even particularly interested in, which didn’t make me happy at all.

The problem with the reining in however, in letters like William Morrow’s and elsewhere, is not that publishers are asking more of bloggers or that bloggers are practicing book banditry, but rather that the publishers are treating the bloggers like kindergarteners. There is an abject disregard here by publishers of what bloggers do, no understanding of their function beyond that of unpaid publicists, and it’s clear that bloggers are not being taken seriously as the force they are. And when I look out at the book blogosphere these days and see such an abundance of unfortunate blogs (enacting many of the problems William Morrow notes in their letter), I’m not sure the bloggers themselves are entirely to blame. Sure, there seems to be a lack of responsibility on behalf of the bloggers, but the publishers are doing absolutely nothing to cultivate an alternative, which it will be very much in their purview to do.

The upside to beginning to receive free books on my blog, along with the overwhelmingness and dangerous sense of flattery, was the notion that someone was taking what I was doing seriously. It was a revelation! And the individuals I was dealing with at various publishing companies did take me seriously, working to create a genuine relationship, reading and engaging with my blog, suggesting books that they’d considered and thought that I would like. Many of these individuals were book bloggers themselves, rather than marketing types straight-up, and so they understood how it worked, that a book blogger requires the autonomy that any reviewer does.

Of course, the book blogosphere was smaller then, so such relationships were easier to foster, and I know that publishers’ resources have become unbelievably stretched in recent years. But I can’t help thinking that publishers themselves could have had more control over what has been the general decline of book blogs (or maybe what I mean is that they had more control than they imagined in the decline itself). Why, for example, do they send books to bloggers whose blogs are terrible? Does it still count as “buzz” if it’s generated by idiots (and it’s probably at this point that you clue in to the fact that I’m really not a marketer, no?)? Why send books to those bloggers who think a “review” is a 50 word assessment, and a pasting of the book’s marketing copy? Why do you send YA books about dragons to 35 year old men who like reading Malcolm Gladwell? The point of bloggers is to create buzz, yes, but that buzz is only going to buzz if it’s coming from a legitmate conversation. And publishers have missed their opportunity to heighten that converation’s tone.

Now I’m sounding like Jaron Lanier, I think, sitting back in my rocking chair wearing my enormous black t-shirt. Back in my day, I’ll tell you, things were different. I lament the decline of the individual voice in book blogs, I hate the standardization, the memeishness. I can’t stand the “In My Mailbox” meme, and I do wonder how anyone finds the times to read all those books, which are so often the very same books that other bloggers are receiving, so that the conversation is an echo chamber, and what is lost for that.

I do hope that the bloggers receiving so many free books continue to do their share as readers by actually buying books– I certainly did my bit with a $240 splurge at Book City last week (and hey everybody, guess what you’re getting for Christmas from me this year!). I want bloggers to keep exploring the fringes of the literary scene, whether it be with new books by independent presses or dusting off old books from the shelves. Blogs have always been interesting for being an alternative to what we might find in our newspaper’s dwindling review pages, and not simply a regurgitation. For the discoveries they yield that no mainstream medium would have been able to bring forth, and for the small, specialized communities they foster. For the genuine connections that happen.

And I don’t hate book bloggers at all, of course (though I am well-versed in writing an attention-grabbing title). I have as much hope for the what we can offer to books and literature in general as I ever did. But I just think that when publishers ask more of us, it should be about not simply towing their line, and that it’s most important that we never stop asking more of ourselves.