December 5, 2011

Kalila by Rosemary Nixon

Earlier this year when I read Charlene Diehl’s memoir Out of Grief, Singing, I marvelled at the way that fiction holds writers to certain constraints, on the way we have to bend life and draw out connections to build a story. And Rosemary Nixon is aware of this in her novel Kalila, the story of a couple whose daughter is born with inexplicable complications and spends her life in an isolette in the NICU. A novel like this refuses to conform to narrative expectations; as Nixon’s protagonist Maggie tells us, “Stories are meant to lead somewhere. To rising action. Climax. Closure. And they lived Happily Ever After.” Of course, a story like Kalila’s takes on a different shape.

Earlier this year when I read Charlene Diehl’s memoir Out of Grief, Singing, I marvelled at the way that fiction holds writers to certain constraints, on the way we have to bend life and draw out connections to build a story. And Rosemary Nixon is aware of this in her novel Kalila, the story of a couple whose daughter is born with inexplicable complications and spends her life in an isolette in the NICU. A novel like this refuses to conform to narrative expectations; as Nixon’s protagonist Maggie tells us, “Stories are meant to lead somewhere. To rising action. Climax. Closure. And they lived Happily Ever After.” Of course, a story like Kalila’s takes on a different shape.

Which means that as a novel, Kalila is not immediately satisfying, that the narrative is set up in a way that puts the reader at a distance, that the approach is clinical, but this was never a story that was going to satisfy. And Nixon knows exactly what she’s doing here: if Maggie appears to be a protagonist in a trance, it’s because she is. If she and her husband Brodie appear to be disconnected from the world around them, from the experience of pregnancy and childbirth, even from the story they find themselves in the midst of, it’s because they’re meant to be. They feel like strangers in their own story, a story in which they never would have cast themselves, one so entirely different than everything they ever expected when they imagined their baby being born, and a reader’s experience is analogous.

Brodie is a high school physics teacher, and his classroom scenes are beautifully choreographed (and they reminded me of Monoceros in this respect, another Calgary book, and Nixon thanks Suzette Mayr as “my writing buddy”, which wasn’t actually a huge surprise). He keeps his mind off his wife’s pain and the plight of his tiny daughter by focusing on particles and waves, on the sound of his students’ happiness, and the strangely bending laws of the universe. And though as a scientist, he knows the way things fall apart, when he’s alone with his daughter, he resorts to fairy tale narratives, and he tells her a story of a tiny princess in a glass castle locked away.

Maggie doesn’t have the diversion of work, but rather the conspicuousness of being a mother without her baby. She struggles with her displacement as nurses and doctors assume care of her child, doctors and nurses who don’t even know what her name is. She longs to love her child in the proper way, but “it’s too late for love at first sight”, she says at one point, and she doesn’t know what to do with herself. Though she notes that the doctors and nurses don’t quite know what to do with her daughter either, whose problems are innumerable and indecipherable, and who isn’t getting any better.

The baby herself is at a remove from all of this, both literally and figuratively. In every sense, she is the unknown variable. There is a coldness to the parents’ approach to their child, a measuredness. They are wary, weary, heartbroken, and numb all at once. An actual acknowledgement of the workings of their hearts at this moment in time would cause either one to stop and break down, but breakdowns aren’t what Kalila is all about. This is a novel about going forward into the unknown, about how a new mother occupies herself at home during the day when her daughter has needles stuck into her head, and about remembering to put the dog out, to eat, to make small talk with acquaitances in the grocery store.

The novel’s restive pace shifts about 2/3 of the way through when Brodie and Maggie decide to bring their daughter home after five months in the hospital, to have the empty space in their lives finally filled. And though they don’t dare utter the word “miracle”, they’re both thinking it. But as Nixon, of course, has already told us, this rising action is never going to lead to closure, to happily ever after. This ending has always been an inevitable thing.

I’m attracted to stories like this for less than savoury reasons perhaps. There’s a voyeuristic element to it, and one with especially self-serving motives. To me, reading books like these is a way to stare down my very worst fears, to not look away for as long as I can, and imagine that somehow this staring might prepare me for all those things one can never be prepared for. Though I’m not fooling anyone, of course, let alone myself. Further, Nixon writes with a precision that doesn’t really tolerate such self-indulgence on my part. In Kalila, there is no such thing as indulgence– it’s all about the story, and the peculiar shape that lives take on when stories shift into such unimagined terrain.

December 4, 2011

On urban picture books, and concepts of home

I was holding Harriet’s hand the other day as we walked up the flight of stairs to our door when I heard her say under her little-girl breath, “four flights of stairs to family’s apartment.” I recognized it as a line from Corduroy, and asked her, “Whose apartment?” She said, “Lisa’s.” I said, “Did you know that we also live in an apartment?” She said, “No. We live at home.”

I was holding Harriet’s hand the other day as we walked up the flight of stairs to our door when I heard her say under her little-girl breath, “four flights of stairs to family’s apartment.” I recognized it as a line from Corduroy, and asked her, “Whose apartment?” She said, “Lisa’s.” I said, “Did you know that we also live in an apartment?” She said, “No. We live at home.”

I appreciate Don Freeman’s illustrations in Corduroy, probably for similar reasons black parents would have appreciated them when the book was published in the 1960s: here is a picture book that reflects the reality of my child’s life. Lisa’s is an urban world, with stairwells, department stores, laundromats and sidewalks. And it’s a world far removed from the one that I grew up in, at the end of a cul de sac, with a big backyard. I grew up in neighbourhoods where they didn’t even have sidewalks, and the only store nearby was a Beckers. The families we looked down upon were those with single-car garages, and the families who looked down on us had driveways made from interlocking brick.

Such a childhood served me well– who needs sidewalks when you can play in the street? And manicured lawns are fine and well when there are ravines to explore, and creeks to wade in, and games of Nicky Nicky Nine Doors to be won. But the choices we made for our family would be different– we want to be able to walk to our places of work, and not have to work so much, and not working so much means we don’t own a house, and not owning a house means we get to live in the apartment of our dreams in a neighbourhood close to the places where we work, and so it goes, a most unvicious cycle.

Ours not such an unusual choice, of course, and this is underlined by the so many wonderful children’s books these days depicting urban life. In fact, some of these books commodify urban life to such hipsterish effect– I’m thinking about Urban Babies Wear Black, or the various board books we own about sushi. We’re big fans of Mo Willems’ Knuffle Bunny Books, and for a long time, I would read these and wonder if Harriet’s urban life wasn’t urban enough, and were we denying her a proper childhood in a Brooklyn brownstone? And then I read an article about the time Willems has to spend photoshopping the unsavoury elements of his neighbourhood out of the books’ photographic illustrations, and came to terms with our urban life as it is.

Ours not such an unusual choice, of course, and this is underlined by the so many wonderful children’s books these days depicting urban life. In fact, some of these books commodify urban life to such hipsterish effect– I’m thinking about Urban Babies Wear Black, or the various board books we own about sushi. We’re big fans of Mo Willems’ Knuffle Bunny Books, and for a long time, I would read these and wonder if Harriet’s urban life wasn’t urban enough, and were we denying her a proper childhood in a Brooklyn brownstone? And then I read an article about the time Willems has to spend photoshopping the unsavoury elements of his neighbourhood out of the books’ photographic illustrations, and came to terms with our urban life as it is.

Urban life presented how it is is why we love Bob Graham’s Oscar’s Half Birthday, with the graffiti in its streets and the wonderful rumble of the train overhead. It’s why we love Subway by Anastasia Suen and Karen Katz (“We go down to go uptown. Down down down in the subway”). Joanne Schwartz and Matt Beam’s City Alphabet and City Numbers present city grit in all its glory. And Don Freeman’s contemporary too, Ezra Jack Keats, whose sidewalks and alleys are ways of delight. Even Shirley Hughes’ books with their domestic focus have the city as their backdrop– buses, stoops, parks and traffic.

We are fortunate that some of our very favourite urban stories are set in the city where we live: Allan Moak’s A Big City ABC, poems from Alligator Pie, Who Goes to the Park by Warabe Aska, Jonathan Cleaned Up and Then He Heard a Sound by Robert Munsch, and when Harriet’s bigger, I hope she’ll enjoy Bernice Thurman Hunter’s Booky books as much as I did. One of our favourite books of all time is Teddy Jam’s Night Cars, set against a Toronto streetscape, and we love the familiar TTC as presented in Barbara Reid’s The Subway Mouse. (Find more Toronto kids books as recommended by Imagining Toronto‘s Amy Lavender Harris.)

We are fortunate that some of our very favourite urban stories are set in the city where we live: Allan Moak’s A Big City ABC, poems from Alligator Pie, Who Goes to the Park by Warabe Aska, Jonathan Cleaned Up and Then He Heard a Sound by Robert Munsch, and when Harriet’s bigger, I hope she’ll enjoy Bernice Thurman Hunter’s Booky books as much as I did. One of our favourite books of all time is Teddy Jam’s Night Cars, set against a Toronto streetscape, and we love the familiar TTC as presented in Barbara Reid’s The Subway Mouse. (Find more Toronto kids books as recommended by Imagining Toronto‘s Amy Lavender Harris.)

The urban setting in children’s literature has become one we can almost take for granted over the past 50 years, thanks to pioneering author/illustrators like Freeman and Keats. These days, children’s books are working to further broaden notions of home in stories like Maxine Trottier’s Migrant, about a young girl belonging to a family of itinerant workers. In Laurel Croza’s award-winning I Know Here, a girl whose home is a trailer in Northern Saskatchewan contemplates a move across the country to Toronto, and takes stock of all she knows and loves about the place where she lives. Martha Stewart Conrad‘s books (we like Getting There) show children from communities all over the world enacting various versions of every day life, portraying the fascinating ways in which we’re all alike and different at once.

How wonderful that my child’s storybook worlds can be as diverse as the one we see outside our window. And once she understands that home is a concept that is broader than just this place where we live, she’ll know how hers fits in with all the rest of them.

December 2, 2011

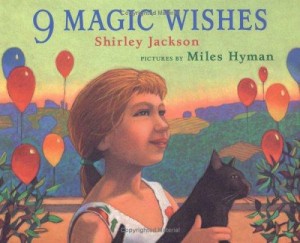

Our Best Book of the Library Haul: 9 Magic Wishes by Shirley Jackson

Harriet is amazing, and so too turn out to be the books she randomly plucks off the shelf at the library. And this week it was 9 Magic Wishes by Shirley Jackson, a book I didn’t even realize existed. This new edition is illustrated by Miles Hyman, Jackson’s grandson, who so perfectly managed to capture the essence of Shirley Jackson: the Gothic architecture of the house, the cat’s constant presence, the weirdness. But there is nothing sinister here, and the book is absolutely charming. The prose displaying Jackson’s skill with cadence and euphony. It’s the story of a strange day during which all the trees were flying balloons, and a magician came down the street granting 9 magic wishes, but what if you only want 8? (My favourite wish was “a little box, and inside was another little box and inside is another little box and inside is another little box and inside is an elephant.”)

Harriet is amazing, and so too turn out to be the books she randomly plucks off the shelf at the library. And this week it was 9 Magic Wishes by Shirley Jackson, a book I didn’t even realize existed. This new edition is illustrated by Miles Hyman, Jackson’s grandson, who so perfectly managed to capture the essence of Shirley Jackson: the Gothic architecture of the house, the cat’s constant presence, the weirdness. But there is nothing sinister here, and the book is absolutely charming. The prose displaying Jackson’s skill with cadence and euphony. It’s the story of a strange day during which all the trees were flying balloons, and a magician came down the street granting 9 magic wishes, but what if you only want 8? (My favourite wish was “a little box, and inside was another little box and inside is another little box and inside is another little box and inside is an elephant.”)

December 1, 2011

Big Town: A Novel of Africville by Stephens Gerard Malone

I read Stephens Gerard Malone’s Big Town: A Novel of Africville this week as the story of the crisis of Attawapkiskat unfolded in the media, and each story so illuminated the other. The story of a Canadian community whose people live in unheated shacks with no running water, with no access to safe drinking water. A community of people treated as second-class citizens by the rest of the world– Malone writes about how hydro lines were down, Africville was always the last place the electric company came to, and usually when you called the police, they never came at all. A community for which the outside world purports to know what’s best, applying simple solutions to complicated problems, solving exactly nothing, and never mind all that gets lost.

I read Stephens Gerard Malone’s Big Town: A Novel of Africville this week as the story of the crisis of Attawapkiskat unfolded in the media, and each story so illuminated the other. The story of a Canadian community whose people live in unheated shacks with no running water, with no access to safe drinking water. A community of people treated as second-class citizens by the rest of the world– Malone writes about how hydro lines were down, Africville was always the last place the electric company came to, and usually when you called the police, they never came at all. A community for which the outside world purports to know what’s best, applying simple solutions to complicated problems, solving exactly nothing, and never mind all that gets lost.

Africville was a black settlement outside of Halifax Nova Scotia, razed during the 1960s by the city for reasons of public health and progress. Malone situates his novel in the community’s dying days, showing that social order had broken down by this time, as it had in so many communities during that turbulent decade. Africville had become conspicuous by its proximity to the town dump, and to the unsavoury characters attracted to its fringes, like Early Okander’s father.

However, Early himself, who is white, a white simple-minded teenager devoted to his young friend Toby, is embraced by the community, and cared for by its residents all the while his father beats him and prostitutes him to his poker buddies on Saturday nights. In contrast to the trailer where Early and his father lives, Toby’s home with his grandfather Aubrey is a domestic oasis, supplied with nourishing food by neighbouring Mrs. Aada who owns the local store, and the company of other neighbours who remember a better time when the community was strong and thriving. It is as a testament to this better time that Aubrey is building a concert hall out of used bottles as a performance space for the Miss Portia White, the world famous singer who’d once lived in Africville and who, according to Aubrey, would be making a pilgrimage home now any day to help restore the community to its former glory.

The novel is meant to be told from Early’s perspective, though Malone refrains from the Faulkner-esque challenge of letting such a limited perspective wholly take over. Which makes Big Town a less challenging read, albeit one less narratively interesting. Malone plays with the ambiguity of Early’s point of view at times, but never so ambitiously, and the read between the lines is more obvious than it would like to be.

In many ways, Malone’s novel has more in common with a book like To Kill a Mockingbird, complete with its own Scout Finch in Early and Toby’s friend Chub, a girl who wants to be a boy and cuts her own hair with paper scissors. Though the story being filtered through the children’s point of view lacks the weight and nuance of To Kill a Mockingbird, however much that’s a high standard to hold any book to. The bleakness is also unrelenting– both Toby and Chub engage in self-harm, Aubrey is battling his own demons, Early’s father’s acts of violence against him are devastating; whither art thou, Atticus Finch?

Though that Malone proposes no saviour is wholly understandable, because certainly Africville never managed to be saved. And though at times I felt that the children’s perspectives were so limited as to simplify the story behind them, that story held fast my attention. Malone has made vivid a time and place thought lost to history, broadening the range of stories that we call Canadian.