October 16, 2011

Not Being on a Boat by Esme Claire Keith

There was so much right about Esme Claire Keith’s novel Not Being on a Boat that I was planning to review it here anyway, even though there was one thing quite wrong. The one thing being its length, of course, and that being trapped in the mind of her Mr. Rutledge for 350 pages was just too much, but that it was so thoroughly too much was because her Mr. Rutledge was so spotlessly executed. A divorced retiree jacked up on the force of his own consumer power, he has bid farewell to the world and boarded the good ship Mariola to sail off into the sunset. Equipped with two tuxedos and a taste for the finer things in life, he’s expecting good value for his money and some fine conversation with the other passengers in the Captain’s Mess.

There was so much right about Esme Claire Keith’s novel Not Being on a Boat that I was planning to review it here anyway, even though there was one thing quite wrong. The one thing being its length, of course, and that being trapped in the mind of her Mr. Rutledge for 350 pages was just too much, but that it was so thoroughly too much was because her Mr. Rutledge was so spotlessly executed. A divorced retiree jacked up on the force of his own consumer power, he has bid farewell to the world and boarded the good ship Mariola to sail off into the sunset. Equipped with two tuxedos and a taste for the finer things in life, he’s expecting good value for his money and some fine conversation with the other passengers in the Captain’s Mess.

The devil is in the details, however, all of which Rutledge notices, astute businessman (and borderline autistic) that he is, forever on the lookout for number one. But such details and this perspective doesn’t make for great reading, not 350 pages of it, as we learn about the ship’s laundry procedures, and what’s available on the menu, and the historical facts even Rutledge fast tires of as delivered by guides giving tours at the ship’s ports of call. The flawlessness of Keith’s narrative makes reading really hard-going, though things outside Rutledge’s head are certainly interesting: we receive glimpses of the distopian civilization that Rutledge has left behind him, and the problems come aboard the Mariola when one day a group of passengers and some crew fail to return from a port of call. Suddenly, the ship’s standards begin slipping, supplies are getting low, communications are shut down from the outside world, and the problems of the outside world are creeping in through the portholes.

The devil is in the details, however, all of which Rutledge notices, astute businessman (and borderline autistic) that he is, forever on the lookout for number one. But such details and this perspective doesn’t make for great reading, not 350 pages of it, as we learn about the ship’s laundry procedures, and what’s available on the menu, and the historical facts even Rutledge fast tires of as delivered by guides giving tours at the ship’s ports of call. The flawlessness of Keith’s narrative makes reading really hard-going, though things outside Rutledge’s head are certainly interesting: we receive glimpses of the distopian civilization that Rutledge has left behind him, and the problems come aboard the Mariola when one day a group of passengers and some crew fail to return from a port of call. Suddenly, the ship’s standards begin slipping, supplies are getting low, communications are shut down from the outside world, and the problems of the outside world are creeping in through the portholes.

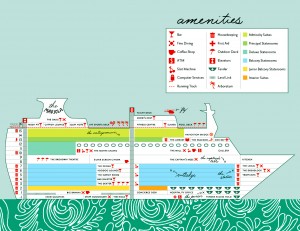

The novel concludes with an end-of-days scenario that had me furious: 350 pages for this? But as the fury wore off, I decided to write about the book anyway because Keith’s control of her project was so impeccable, and also because I’m not sure there was any other way she could have ended it. Not Being on a Boat is a marvelous satire of consumer culture and luxury tourism, so smart and funny, deadpan and sharp. (It is also beautifully designed by kisscut book design, including the map of the boat I discovered under the back flap). And sometimes a flawed book really can still portend the debut of a really great writer, so though “less is more” would really go a long way here, I’d say Keith is one to keep an eye on, and I’d check out what she comes up with next.

I have this on my tbr pile and I love all the good things you’ve said about it. While the length bothered you, and the ending a bit too, what praise you gave was high. I look forward to it!

Love the map!

My reading of Keith’s debut novel at first had me cursing the endless minutiae of Rutledge’s daily life on the cruise — I got what she was doing with it, but it felt absolutely stultifying and I believe the same thing could have been done in fewer pages. But at the same time I was mesmerized. Once the ship’s resources began to run out and communications grew increasingly compromised, the writing was on the wall and an increasing sense of foreboding began to grow in me. Of course the ending can be anticipated. But there’s something so much more ominous about Rutledge’s journey to said end than there would have been if Keith’s protagonist were more “normal”… that is, with a “normal” emotional makeup,rather than with Rutledge’s peculiar kind of self-centredness. I found the last couple of pages so disturbing – even though i had found it inevitable, it still came as a visceral shock — that I had to re-read it the day after, to really digest what seemed to me rendered with a bleak and icy perfection.

The most disturbing thing for me is that the cruise ship, Rutledge and the others aboard are metaphors for this earth and for us, its inhabitants. As a species we are supremely self-centred, to the point of being myopic, and we downwardly adjust our expectations as the earth’s resources run low, just as Rutledge downwardly adjusts his as the ship’s supplies run low. Without even noticing that we’re doing so, really (because actually, do we even want to think about the overall picture? It would just be too much to truly digest!). If Rutledge is a self-absorbed monster with an overblown sense of entitlement, expecting his full share (of whatever happens to be left), then so – as a group – are we.

Overall it’s a damn chilling picture if viewed as metaphor.

DeeM

Thanks for your comment. I agree that the book is a tough read for all the wrong reasons, but it also very worthwhile. And seems much less absurd when viewed against the Costa Concordia shipwreck, no? Truth is strange.