August 31, 2011

Natural Order by Brian Francis

Whereas Brian Francis’ novel Fruit (which should have won and nearly did win Canada Reads 2009) was a hilarious little story with an undercurrent of sadness, his second book Natural Order is a sad huge story with an undercurrent of hilarity. Fruit ended with Peter Paddington on the cusp of his teenage years, his dawning awareness of his homosexuality, of a darkness on the horizon. The darkness was so subtle you might have missed it in this deceivingly light novel, and it is this darkness that Francis tackles in this latest book.

Whereas Brian Francis’ novel Fruit (which should have won and nearly did win Canada Reads 2009) was a hilarious little story with an undercurrent of sadness, his second book Natural Order is a sad huge story with an undercurrent of hilarity. Fruit ended with Peter Paddington on the cusp of his teenage years, his dawning awareness of his homosexuality, of a darkness on the horizon. The darkness was so subtle you might have missed it in this deceivingly light novel, and it is this darkness that Francis tackles in this latest book.

The book begins with a death notice from 1984, John Sparks dead of a sudden illness at the age of 31. He is survived by his parents, aunts and uncles, and cousins. And then in the first chapter, we meet his mother Joyce years later, living out the final years of her life in an old age home. Her husband has died, she had no other family, and hers is a lonely life that has caused her to grow a brittle shell. Her one diversion is visits from a volunteer called Timothy, a young man who is gay, and though she at first resists his attempts at connection, she warms to him because he reminds her of her son.

Times run together for the elderly, blurred borders between yesterday and today, and so accordingly, Joyce’s narrative reaches out in a variety of directions. In her youth, she’d developed a crush on a flamboyant co-worker who later commits suicide; we meet Joyce as a young mother delighting in her son; years later, she is dealing with the distance of a son whose true life she refuses to acknowledge (which makes his death, from AIDS, all the more painful. Not that she learns from this– she tells everyone he’s died of cancer). A major componant of the plot involves Joyce as a widow, still living in her home but becoming aware that her days there are numbered, and a discovery she makes that forces her to acknowledge her shortcomings as a mother and a wife.

The delights of this novel are many– Francis writes with a steady hand, creating believable characters who talk and act like people do. I particularly loved Joyce’s friends and neighbours– her single friend Fern in the red sequinned shirt, and her neighbour Mr. Sparrow who calls her to warm her about a strange man prowling around her house, who he’s since invited in for a coffee. Also, jokes about United Church Women who can whip up “a salmon loaf standing on [their] head[s] in thirty seconds”. Though my favourite joke is when Joyce goes over to visit a friend whose father had years before fallen off the roof during a lightning storm: “Stay off the roof,” my father said.

At times, Joyce seems too aware of her role in the story (“But the only way I could control things was if John went to the college here and stayed at home”), but for the most part, Francis has done a stunning job of getting into this character’s mind and creating sympathy for her. He shows Joyce’s overbearing nature as the result of a mother’s efforts to protect a boy who always had a hard time fitting in and faced persecution at school, and her refusal to acknowledge just how exactly he was different as a product of her time and culture.

I’m not crazy about the cover of this book– the whole point of Joyce is her unworldliness, and that she spent her whole life quite sure that the world in her backyard was the world as it was, and what I mean is that she never took her son to the seaside. But her stubbornness in clinging to her own view in the world is what makes her such a compelling narrator. At the end of a life of deception, she becomes quite adept at unflinching truths. She is wry, funny, and far more observant of others’ true nature than perhaps she ever wanted to be.

Brian Francis’ prose is wonderfully readable, he has a talent for perfect detail, though perhaps the novel’s greatest strength lies in how the many different story-lines and time-lines are woven together seamlessly. His generosity with happy endings is measured out just enough to be believable, but also for the novel to be uplifting, and Joyce Sparks is certainly a worthy addition to the canon of Hagar Shipley, Georgia Danforth Whitely, Daisy Stone Goodwill etc.: “I am not at peace.”

August 30, 2011

Here be (no) dragons

One day, after ages of it being beloved, Harriet suddenly refused to let me read Sheree Fitch’s Sleeping Dragons All Around. At that point, she was unable to articulate why, but it was still significant as the first time a book had been outright rejected (as opposed to, say, abandoned out of boredom, which is different).

One day, after ages of it being beloved, Harriet suddenly refused to let me read Sheree Fitch’s Sleeping Dragons All Around. At that point, she was unable to articulate why, but it was still significant as the first time a book had been outright rejected (as opposed to, say, abandoned out of boredom, which is different).

She also wouldn’t let us read her The Lady With the Alligator Purse— we’re still not sure why. But by the time she’d gone off two books as various as Neil Gaiman’s Instructions and Robert Munsch’s The Paper Bag Princess, I’d started detecting a theme. And by this time, Harriet had the words to explain: “Too scary,” she told us. Apparently it’s a fire-breathing dragon thing.

But how did she discover that dragons were scary? I’d certainly gone out of my way never to mention such a thing. In fact, I’d never mentioned that there was such a thing as “scary” at all, because little people are so open to suggestion, and I’ve been working hard on cultivating fearlessness. I don’t really do “scary” anyway, except when it comes to sensible things like diving off cliffs and tightrope walking. The closest thing I’ve got to an irrational fear is an extreme unease around dogs (which is not so irrational, I’d argue, because they’re equipped with teeth that could chew your face off), but I promise you that around a dog, Harriet has never, ever seen me flinch.

So this dragons thing has brought me to the limits of my powers, my powers of “cultivation”, and I get it that this is only the beginning of a very long education. And I get it too that it doesn’t take a genius to deduce that oversized fire-breathing lizards are probably best left undistubed between covers. (Interestingly, Harriet’s dragon aversion doesn’t extend to dinosaurs. She loves dinosaurs–plush, fossilized, wooden, Edwina, you name it.)

The thing is actually, that I fucking hate books with dragons (some excellent picture books aside). It’s true. I always have– when I was growing up, I never read a single book with a dragon on the cover. Which wasn’t really difficult to accomplish, because there weren’t many books with dragons on the cover. (My YA self would have been horrified by the popularity of science-fiction/fantasy today. And my adult self remains mystified.) A dragon on the cover was a kind of book design shorthand for “boring book for nerds”, and though I was certainly a nerd, I was the type of nerd who preferred books about pretty girls dying of anorexia or getting cancer.

Fantasy books: here’s another place where I’ve come to the limits of my own powers. I just can’t get into them, though I’ve tried. And I think back and wonder if I’d been less dragon-phobic in my youth, maybe fantasy-appreciation would come easier to me. There are a lot of things I wish I’d spent most of my life being a lot more open minded about, hence the reason why I want to make Harriet’s literary horizons broad from the very start. I want her to read better than I did, but then she persists in having her own feelings about things. She persists in refusing to be malleable, in having fears and preferences and in being a person apart from me.

But also a person who is very much like me, which I’m not sure is more or less disconcerting.

August 29, 2011

Swearing in the margins

One of the nicest things that happened to me earlier this summer was receiving the opportunity to write for UofT Magazine (which published my story “Georgia Coffee Star” two years ago). Even better, my assignment required me to read Ray Robertson’s Why Not? Fifteen Reasons to Live, which was so provocative that I kept swearing in the margins first read through. (This proved to be embarrassing when I had to pass the book on to a fact checker). Upon second reading, however, I really understood and admired what Robertson was up to with this book, even though I didn’t always agree with him.

As I wrote, “Never, ever boring, within the wild trajectory of each piece, Robertson backtracks, repeats himself, changes his mind and displays his characteristic ribald humour. Why Not? is intentionally provocative, stirring readers to vehemently agree or disagree. But this is Robertson’s point: to be stirred at all, regardless.”

You can read the whole thing here.

August 28, 2011

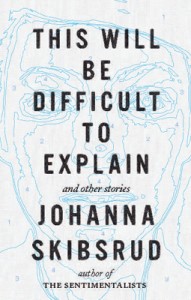

This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories by Johanna Skibsrud

It’s not quite what you’d explect, This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories, Johanna Skibsrud’s first collection of short fiction. Though what we’re meant to expect from Skibsrud is hard to tell exactly– she’s the author who published her novel with an artisanal small press then won the Giller Prize, the recent overnight success with (now) four books under her belt, the poet whose novel concludes with a court transcript. Johanna Skibsrud appears to exist in order to defy our expectations, and so perhaps it’s smart to just abandon them altogether, and take the stories as they come.

It’s not quite what you’d explect, This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories, Johanna Skibsrud’s first collection of short fiction. Though what we’re meant to expect from Skibsrud is hard to tell exactly– she’s the author who published her novel with an artisanal small press then won the Giller Prize, the recent overnight success with (now) four books under her belt, the poet whose novel concludes with a court transcript. Johanna Skibsrud appears to exist in order to defy our expectations, and so perhaps it’s smart to just abandon them altogether, and take the stories as they come.

The book is slim, and the stories are diverse– presumably, the collection itself has been quickly assembled on the tail of Skibsrud’s Giller fame. Nothing hasty about the assembly of the stories themselves, however, which display the precision some readers found lacking from The Sentimentalists. There are links between a few of them, and each one portrays a character who is “caught at exact point of intersection between impossibility and desire”. Each one demonstrates, as described in the story Fat Man and Little Boy, “that things happen, not at any particular or recordable time, but at an indeterminate midpoint. Somewhere, that is, between the verifiable and measurable tick and the ensuing and otherwise unremarkable, tock… in that incalculable interval of both space and time.”

The collection reminded me of Mavis Gallant’s Home Truths, with its stories of expats, continent-hopping themes, and also the ability of the narrative to telescope in and out of time. In many of the stories, young Canadian or American protagonists are bumbling their way through France, though they’re never aware of the bumbling until after the fact. Skibsrud is good at “after the fact”, her stories full of deft reveals and fitted with fantastic endings.

In “The Electric Man”, a young woman reveals herself to a mysterious man who reveals nothing of himself; in “The Limit”, a single father struggles to connect with his daughter and clings to a landscape which makes his own limits clear; in “French Lessons”, which deals with the struggles of translation, Martha (who we’ll see again in other stories) receives a startling glimpse into an old woman’s loneliness, hears the message on the wrong beat, and responds with inappropriate laughter; “Clarence” is the story of a young local newspaper reporter who inadvertently interviews a corpse (and this ending was my favourite, I think); in “Signac’s Boats”, we meet Martha again, who’s struggling with the immovable limits of her perspective (but then “limits are real”), even as she puts herself out in the world, and then she’s stunned to realize that love is a new kind of limit, “that it simplified her, when she’d thought it would have made her more integral, more complex.”

“Cleats” was my favourite story, I think, the one that really had me thinking about Mavis Gallant (and not just because of Paris). This long, wonderful novel in a story hinges over and over on sudden shifts of perspective, on carpets pulled out from underneath you. A mother’s complicated relationship with a grown daughter as the mother struggles to make her way in the world after leaving her marriage. Another mother-child relationship is sharply depicted in “Angus’s Bull”, another mother who notices with unease that her child “notices everything”. And then “Fat Man and Little Boy” is the story of Martha’s friend Ginny who goes to Japan to visit an old friend, and finds herself strangely moved and unmoved by the Peace Museum at Hiroshima, by thoughts of her own uncle who worked at Los Alamos and is now dying of cancer, by the fact that nothing is ever one thing, that each singular moment contains the entire world.

Skibsrud’s preoccupations become evident throughout this excellent collection– with limits, and how we fixate on them and/or reject them, with where we come from and where we go, with who are parents are and how we fixate on them and/or reject them, with history and the impossibility of fully inhabiting just one single moment. Clearly Johanna Skibsrud is as at home in the short story form as she is throughout the rest of them, and my expectations have been more than met. I’m more intrigued by this author than ever before, and convinced that Ali Smith was onto something after all.

August 27, 2011

Toronto Saturday (and books)

We’re kind of allergic to crowds, so we tend to go to where they don’t go. But perhaps another way to honour Jack Layton is to spend a good Toronto Saturday, and that’s what we did. We hauled ourselves out of bed (which was difficult. We’d spent last night watching The Long Good Friday, which is the best movie we’ve seen in ages, and it was hard to fall asleep after that) and walked through Little Italy down to Queen Street West, and met our friends in Trinity Bellwoods Park for some caffeine and Clafouti croissants. And then we crossed the street to Type Books to attend the

We’re kind of allergic to crowds, so we tend to go to where they don’t go. But perhaps another way to honour Jack Layton is to spend a good Toronto Saturday, and that’s what we did. We hauled ourselves out of bed (which was difficult. We’d spent last night watching The Long Good Friday, which is the best movie we’ve seen in ages, and it was hard to fall asleep after that) and walked through Little Italy down to Queen Street West, and met our friends in Trinity Bellwoods Park for some caffeine and Clafouti croissants. And then we crossed the street to Type Books to attend the  launch of This New Baby, a book by Teddy Jam with new illustrations by textile designer Virginia Johnson. Which meant that Virginia Johnson read us stories, and we got to eat yummy cheese.

launch of This New Baby, a book by Teddy Jam with new illustrations by textile designer Virginia Johnson. Which meant that Virginia Johnson read us stories, and we got to eat yummy cheese.

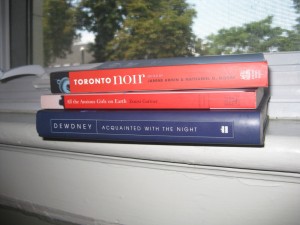

We bought a copy of the book for ourselves, a few for friends, and somehow a copy of Lynn Coady’s The Antagonist fell into my purchases. Then we walked home via Kensington Market where we had a good lunch. Also via a yardsale just up the street–the best thing about my neighbourhood is that it’s full of writers and university professors, so the book selection at the yardsales is always top-notch (if not a bit weird/specialized. A lot of Holocaust Studies, Lesbian Short Fiction Anthologies, and Irritation Bowel Syndrome books at this one). I got Toronto Noir, All the Anxious Girls on Earth, and Acquainted With the Night.

August 26, 2011

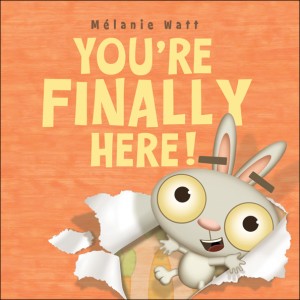

Our Best Books from this week's library haul: Big Wolf & Little Wolf and You're Finally Here

I do like my picture books to have a message, but one curled up so tiny in the core of the story that you don’t even notice it until you think about it. We don’t like our picture books to patronize, of course, and a little silliness is always welcome, but as a student of literature, I am accustomed to deconstructing the best books and coming up with something, something greater than the whole.

I do like my picture books to have a message, but one curled up so tiny in the core of the story that you don’t even notice it until you think about it. We don’t like our picture books to patronize, of course, and a little silliness is always welcome, but as a student of literature, I am accustomed to deconstructing the best books and coming up with something, something greater than the whole.

In Nadine Brun-Cosme and Oliver Tallec’s Big Wolf & Little Wolf, I suppose that something is a message about an older sibling’s fear of his place being usurped by a younger. I think a child who’s experiencing such fears could be led to some good conversations by discussing this book, but this is not the reason this is one of our favourite books this week. No, we like it because Brun-Cosme has named her two wolves Big Wolf and Little Wolf, and when you’re two years old, the big/little  dichotomy is endlessly fascinating. Also, because when you’re two, you feel an affinity with “little” things. When Little Wolf (who’s moved into Big Wolf’s territory in a way that’s quite presumptuous) disappears, Harriet becomes very concerned. “Where is Little Wolf?” she asks on every page, and then when we finally catch a glimpse of Little Wolf way off on the horizon, she feels as though she’s done something heroic in locating him. It’s a story about friendship, love and sharing: “For the first time he said to himself that a little one, indeed a very little one, had taken up space in his heart. A lot of space.” And let’s face it, we all know what that’s like…

dichotomy is endlessly fascinating. Also, because when you’re two, you feel an affinity with “little” things. When Little Wolf (who’s moved into Big Wolf’s territory in a way that’s quite presumptuous) disappears, Harriet becomes very concerned. “Where is Little Wolf?” she asks on every page, and then when we finally catch a glimpse of Little Wolf way off on the horizon, she feels as though she’s done something heroic in locating him. It’s a story about friendship, love and sharing: “For the first time he said to himself that a little one, indeed a very little one, had taken up space in his heart. A lot of space.” And let’s face it, we all know what that’s like…

Bonus: Our bonus book of the week is You’re Finally Here by Melanie Watt, which we can’t take any credit for discovering because the librarian handed it to us. It’s a bit of a metafictional riff of Mo Willems’ We Are In a Book, except that the bunny rabbit here has no qualms about being a storybook character. He’s just bored, waiting for the reader to finally arrive, and then when we do, he can’t quite hold his tongue– What took us so long? Because he hates waiting, and it’s rude to keep someone waiting, and he so harangues us in a most amusing fashion with blazing text and fury that Harriet finds funny. And then his cell-phone rings, and we discover who’s the rude one after all…

August 25, 2011

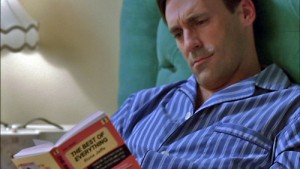

The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe

I still haven’t watched the fourth season of Mad Men— I’d like to fix the world in order to have Mad Men perpetually before me. We recently rewatched Season 1 though, and got so much out of it– partly because we watched it first time around when Harriet was still so small, so concentration was limited, plus somehow we missed the pivotal “Babylon” episode, so no wonder I felt the narrative was a little out of sync. It’s an extraordinarily good show, no doubt about it now. Though I have feelings for Don Draper in a way that I haven’t harbored for any imaginary person since Dylan McKay in the early 1990s.

I still haven’t watched the fourth season of Mad Men— I’d like to fix the world in order to have Mad Men perpetually before me. We recently rewatched Season 1 though, and got so much out of it– partly because we watched it first time around when Harriet was still so small, so concentration was limited, plus somehow we missed the pivotal “Babylon” episode, so no wonder I felt the narrative was a little out of sync. It’s an extraordinarily good show, no doubt about it now. Though I have feelings for Don Draper in a way that I haven’t harbored for any imaginary person since Dylan McKay in the early 1990s.

My Mad Men reading also continues– I’m still making my way through The  Collected Stories of John Cheever. For literary illumination into Betty Draper, I had the pleasure of The Torontonians last winter. And I’ve just finished reading The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, which is a little bit Peggy Olson, a little bit Joan Holloway, not to mention a book that Don Draper himself was seen reading once in bed. (He looks at Betty. “This is fascinating.”)

Collected Stories of John Cheever. For literary illumination into Betty Draper, I had the pleasure of The Torontonians last winter. And I’ve just finished reading The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, which is a little bit Peggy Olson, a little bit Joan Holloway, not to mention a book that Don Draper himself was seen reading once in bed. (He looks at Betty. “This is fascinating.”)

The Best of Everything is the story of a group of women working at a publishing company in New York City during the early 1950s. Their lives are not especially intertwined, the narrative follows them separately, but they each begin in the same place, working in the typing pool. Smart, beautiful Caroline Bender has been recently jilted by her fiance and is looking for a way to direct her life without him– she has her sights on becoming an editor, but her boss Miss Farrow knows it and is determined to keep Caroline from succeeding (because there is only so much success for women to go around, of course.)

April Morrison is a gorgeous girl from Colorado with no such ambition. She just wants to fit in, and she does after a while. Once she figures out how to reject the advances of her lecherous boss, that is, and reinvents herself with a stylish haircut and new clothes paid for on her charge card. When she lands herself a rich boyfriend, she figures she’s got it made, and it takes her a long time (and an abortion) to realize that he’s been stringing her along. Ever the optimist, however, she starts sleeping with every other boy who comes along in home that one of them will fall in love and make her the wife she yearns to be.

April Morrison is a gorgeous girl from Colorado with no such ambition. She just wants to fit in, and she does after a while. Once she figures out how to reject the advances of her lecherous boss, that is, and reinvents herself with a stylish haircut and new clothes paid for on her charge card. When she lands herself a rich boyfriend, she figures she’s got it made, and it takes her a long time (and an abortion) to realize that he’s been stringing her along. Ever the optimist, however, she starts sleeping with every other boy who comes along in home that one of them will fall in love and make her the wife she yearns to be.

Caroline’s roommate Gregg only lasts at the publishing company a short time. She’s an actress, and she has promise, and she also has a prized contact in David Wilder Savage, the theatre director who becomes her boyfriend. Or he’s kind of her boyfriend– when they show up at the same parties, he always brings her home, but she can never stay. She longs to sew curtains for his bare kitchen windows, and in spite of the openness, there’s always more going on in his life than she is privy to. Eventually, he puts her at a distance and that begins to make do some crazy things.

Then there’s Barbara Lemont, who’s divorced and relies on her job to support her little daughter. When someone finally falls in love with her, every single thing is right about him except that he is married. And there’s Brenda, who’s getting married, and Mary Agnes the office gossip, who is getting married too, and for those two, the job is a stop-gap. But then it never is entirely: “It’s funny, she thought, that before she had ever had a job she had always thought of an office as a place where people came to work, but now it seemed as if it was a place where they also brought their private lives for everyone else to look at, paw over, comment on and enjoy.”

with her, every single thing is right about him except that he is married. And there’s Brenda, who’s getting married, and Mary Agnes the office gossip, who is getting married too, and for those two, the job is a stop-gap. But then it never is entirely: “It’s funny, she thought, that before she had ever had a job she had always thought of an office as a place where people came to work, but now it seemed as if it was a place where they also brought their private lives for everyone else to look at, paw over, comment on and enjoy.”

It’s all a bit of a soap opera, and the endings are too easy, but it all culminates into something more than that, and the book becomes utterly absorbing. Fascinating too that these are the women John Cheever’s characters leave behind when they take the train to Westchester at the end of the day, the kind of women that Betty Draper and Karen Whitney wonder about, when Betty and Karen are the women these women long to be. Almost. And it reminds me of the thing I keep forgetting whenever I think about 20th century history, which was that people were having sex in the 1950s, and willy-nilly to boot. That the more things change, the more they stay the same, and why do stories of beautiful people with terrible lives always seem so incredibly appealing?

August 24, 2011

The Vicious Circle reads Hell by Kathryn Davis

There are some books that make us suspect rumours of the Vicious Circle’s awesomeness might just be overstated. And also that we chose our books back in March with a bit too much zeal and too little caution because, yet again, one of our books has conspired to kill us. This book was Hell by Kathryn Davis, whose cover made us think we’d love it, and we did love it, in parts, but in other parts it made us want to die, fall asleep, close the book and/or fling it against the wall.

There are some books that make us suspect rumours of the Vicious Circle’s awesomeness might just be overstated. And also that we chose our books back in March with a bit too much zeal and too little caution because, yet again, one of our books has conspired to kill us. This book was Hell by Kathryn Davis, whose cover made us think we’d love it, and we did love it, in parts, but in other parts it made us want to die, fall asleep, close the book and/or fling it against the wall.

One of us had a library copy of the book which featured a sticker on its spine that said, “Suspense”, and we figured that sticker had probably resulted in a lot of disappointment for some readers. “Part mystery, part domestic meditation, part horror story” says the back of the book, but we just didn’t get it. Long, long paragraphs of impermeable prose, and even when you took it all apart, the mechanics were generally unclear. Which doesn’t make it seem worth it after a while, to read those paragraphs over, and over, and over.

Some of us came to terms with this by reading it just once and letting Davis’ mesmerizing prose wash over with no concern with meaning. Others came to terms with this by not finishing the book. Those of us who finished the book positively hated the end, and resented Davis for taking the narrative away from the part of the story that most appealed. We liked the 1950s family story, which reminded she of us who’d just read it of Barbara Gowdy’s Falling Angels (except the people were less weird, and the narration was more so). We thought it was cool that this was a Hurricane Hazel story, because we’d never read one that was not Toronto-centric. Most of liked that the story was about the residents of an actual house and the residents of a dollhouse, and the lines between the two were always being blurred. Davis writes about the miniature, about the domestic and its detail. Did we know that medicine cabinets used to have slots in the back where used razor blades could be disposed of? And this is what a house is, an innocent-looking place until you get down between its walls and you find they’ve sliced open your wrist.

“Of course every house in the world, no matter how well-built, will eventually catch fire, blow up, wash away, get knocked down to make way for something new. No matter how durable a house, it isn’t immortal… For this reason the house is jealous of spirit and, as is often the case, becomes possessive. This is why houses are haunted and why, if you love the form of a thing too much, there’s really only one way out.”

There are many stories– the family with the alcoholic mother and philandering father, the eldest daughter who refuses to eat, and who yellow-eyed friend turns up dead due to mysterious circumstances. The narrative goes back and forth in time, and somewhere in time the father is elderly, incapacitated, and lying on the floor after having suffered a stroke. It also goes way back in time to a Mrs. Beetonish character called Edwina Moss whose daughter also refuses to eat and who is preoccupied by Napoleon’s chef. There is food everywhere, but it is disgusting. The domestic is much less heaven and hell, or it is heaven and hell, and the vision of hell is what makes us conscious of our own limitlessness, the magnificence of our construction, the nimbuses surrounding every single hair on our heads, whereas heaven is too finite. And if that doesn’t make any sense to you, know that it didn’t to any of us either.

But it did to somebody. There are readers who have loved this book, and express that it’s not going to appeal to everybody, and that it’s demanding, but the Vicious Circle failed to reap any of the rewards. Which made some of us shrug and say that if we can’t get it, it might not be a great book after all. Others are going to pick it up again sometime, because it might be one of those books that needs five or ten reads to be loved (Hello, Virginia Woolf! And you were worth it too!).

And then we threw our books down because it was still a summer night, the autumn chill distant enough that we can ignore the need for sweaters, and we poured another glass of wine and let talk drift away to other things.

August 23, 2011

P is for Park

I don’t update my blog on the weekends, and due to travel, fun, family and houseguests, this past weekend seems to have leaked well into the week. Much fun has been had, many restaurants have been eaten at, but I’m slowly getting my act together (and finishing The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe. Can’t wait to post about this. Also the latest Vicious Circle recap). In the meantime, here is Harriet living the Big City Alphabet…

August 22, 2011

So let us be loving

“My friends, love is better than anger. Hope is better than fear. Optimism is better than despair. So let us be loving, hopeful and optimistic. And we’ll change the world.” —Jack Layton (1950-2011), August 20 2011