September 30, 2010

Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Alison Pick

I met Alison Pick not through literary circles, but because last year she moved in across the street from one of my dearest friends, which was we how ended up attending a babies program at the library together in the depths of winter, and then I happened to run into her one day while I was buying swim diapers at Shoppers Drug Mart. (See, artists are everywhere, out in the world– it’s amazing).

I met Alison Pick not through literary circles, but because last year she moved in across the street from one of my dearest friends, which was we how ended up attending a babies program at the library together in the depths of winter, and then I happened to run into her one day while I was buying swim diapers at Shoppers Drug Mart. (See, artists are everywhere, out in the world– it’s amazing).

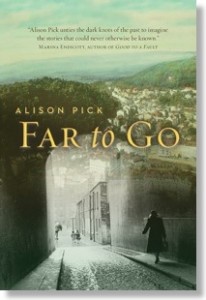

I’d read her first novel The Sweet Edge, and many of her reviews in The Globe & Mail, and I was excited to learn she had a second novel coming out. I read Far To Go over a couple of days in August, and loved it, and it was a pleasure to read it once again in preparation for this interview. Alison and I met up over caffeine and sugar a few weeks ago to get our conversation started, and her little daughter was understanding when Harriet broke her tambourine. Our interview proper was conducted via email during the weeks that followed.

I: I am curious about the idea of adherence to facts in fiction, which becomes much more important in a historical novel than a contemporary one. What kind of factual truths were important for you to achieve in Far to Go as opposed to in your previous novel, The Sweet Edge?

AP: Writing Far to Go was different from writing The Sweet Edge in many ways, one of the primary ones being the need to “get it right” historically. There were two kinds of factual truths I was trying to achieve. Firstly, all the little details needed to line up. Street names, makes and models of cars, kitchen appliances, hair styles: I did a lot of googling, I admit, to ensure all of the above were properly situated in time and place. I wanted all of the small details to work in concert to create the second kind of “truth,’ which was an overall sense of historical aliveness. There’s a danger in historical fiction that the research appears too obvious, too self-conscious. I used hundreds of little facts, but tried to blend them into the background so the reader wouldn’t be conscious of them. Like stitches, I wanted the “facts” of my research, in effect, to disappear within the fabric of the narrative.

I: From a writer’s perspective, what is the relationship between historical aliveness and contemporary aliveness? Issues of period aside, do both kinds of literature “come true” in the same essential ways?

AP: Yes, I think that ideally they do, and that the desired goal is to make the one feel like the other. An historical book needs to be grounded in the small details of its own time and place, but the characters and their motivations should feel entirely contemporary.

I: It’s interesting though that in the present day passages of your novel, we don’t see the same attention to specific detail. Part of this, of course, is that your narrator is to be somewhat of a disembodied voice, but we do come to understand her and her environment even without knowing what shade of nail-polish she’s wearing, for example. So what kind of stitches would you say your narrative is constructed of in these parts of the story?

AP: Yes, good point. The present-day narrator is vague around the edges at the beginning of the story and basically remains so for the duration. Of course, I’m trying to conceal her identity for the purpose of narrative tension, hoping the reader will initially think she is the now-grown Pepik, and then, upon discovering her sex, have to revise. And her theorizing is also somewhat in keeping with her vocation – as a professor of Holocaust Studies focused on the Kindertransport she is uniquely situated to offer overall sweeping commentary on its themes (history, memory, dislocation).

Still, though, I did worry that her vagueness would wind up being a weakness, and tried in various revisions to make her more alive by way of nitty-gritty details. It just didn’t seem to work. At least not in any way I was happy with, and in the end I trusted my original intuition that she was meant to be a different kind of character from Pavel, Anneliese, or Marta. In the final pages Lisa acknowledges that she has chosen to withhold the bulk of her own story, fearing that by revealing too many specifics the overall scope might get lost. So, uh, I’m not sure how that translates in terms of fabric and stitches, but if we can switch to paint, her narrative is created with broad strokes rather than detailed brushwork!

I: I think your intuition was right– these broad strokes come together to create a complex and realized character– perhaps the most realized in the book, as we’re granted access to her thoughts, and everything she’s writing about is so intensely personal. I found a confidence in Lisa’s construction that was not as apparent with the other characters, and this made a great deal of sense once I understand the origins of the historical story.

Were her challenges as a historian (which were to “put what is senseless into a top hat and pull out a knotted scarf of meaning” [and oh, I did like the scarf motif recurring throughout…]) at all analogous to your own as a fiction writer? Isn’t fiction writing also “that need to search for what isn’t there?” How is making a story different?

AP: Well, my first instinct is that being a fiction-writer is a whole lot more fun! But that’s probably just because I’d make an awful academic. The pure pleasure of writing fiction, for me, comes partially from being bound by nothing but the story’s own demands, and having the freedom to follow those demands exactly where the story wants to go. That said, Lisa’s challenge as an historian—as the particular kind of historian that she is—is to create a narrative that is not only truthful but also pleasing to her audience, and that we share. And some of the strictures Lisa works within—those of a particular time and place—were also surprisingly helpful for me when I was writing the novel. I’d underestimated the extent to which an historical backdrop would make the writing easier. Rather than having to constantly fabricate tension, I could relax into the events that actually happened, and that readers are already familiar with, and use them to propel the narrative action.

I: However familiar I am with the history of Nazism, though, the enormity of what transpired makes the whole era seem  impossible. Marta has a similar reaction when she hears of the attack on Pavel’s brother in Austria: “‘I’m so sorry,’ she whispered, but the blanket of fog in her mind had now closed in, and something inside her dismissed the threat entirely. Mr. Bauer clearly had his details confused.”

impossible. Marta has a similar reaction when she hears of the attack on Pavel’s brother in Austria: “‘I’m so sorry,’ she whispered, but the blanket of fog in her mind had now closed in, and something inside her dismissed the threat entirely. Mr. Bauer clearly had his details confused.”

Was it a challenge to render these events as believable? To put hateful and anti-Semitic words in your characters’ mouths, and have those characters still be people (which, of course, is every fiction writer’s objective)?

AP: It was a challenge, yes, but I had the bulk of literature already written about the Holocaust on my side, so I could read how others had done it. And the hateful, anti-Semitic things Marta, at least, says at the start of the story are not so different from the things people are saying all around us today. Part of what I wanted to show in her character was how subtly and gradually hatred can begin. Marta is a “regular” person—a person with a stronger need for approval than the average, maybe, but with the same desire to fit in and to be loved that we all share. Her motives are not actually political, but psychological. It was easy, in fact, to imagine her words as she struggled to know her own mind on the situation unfolding around her, and as she worried about its personal repercussions. Putting those things in her mouth was part of what I hoped made her a believable character.

The other character in Far to Go who is especially anti-Semitic is Ernst, and to have written from his perspective would have been much harder. It was easier as a writer, and as a person, to have him as a classic villain, in stark contrast to the generally good—though obviously fallible—Marta.

I: The remarkable conclusion of Far To Go seems to be that there are some stories that history alone is not equipped to handle, and that art is necessary to really understand our past. Is this something you came to discover as a result of writing the book, or did you suspect it from the outset?

AP: It’s something I believed all along, I think, although writing the book brought it more into consciousness. And as I explored Lisa’s part in the story, I became more certain it was something she as a character would conclude. Toward the end of the book she says that she’s spent her life recording other people’s stories but has chosen to withhold the bulk of her own, for the reason that something always gets lost in the telling. History and the historical method are somehow inadequate to experience—I wonder, would a real life historian ever conclude the same? In any case, for me as a writer, art is infinitely more nuanced, and engaging, and mysterious, and it seemed a safe bet that a reader might feel the same way. And, more importantly, it seemed one of the conclusions toward which everything I’d written had been pointing, even if it wasn’t something I’d initially set out to say.

I: Are you a poet or a fiction writer first, or both, or does it depend on the day? Does the distinction matter? (And here, I will point out that your prose doesn’t read like a poet’s in that way that some critics often complain that a poet’s prose does, so I think maybe the distinction does matter.)

AP: Until recently I probably would have said I’m a poet first, but I’m not so sure anymore. Writing Far to Go was such fun, such a challenge, and such an accomplishment (in the sense that I had no idea how to write an historical novel when I started out, so even finishing it felt like a big deal) and I must admit that I’m eager to write more fiction. In my heart of hearts, I’m a plain old writer first, and my writing just happens to take different forms. I know other writers, poets in particular, who feel that to write prose is to sell out, not just financially but aesthetically or even morally somehow. I do understand the argument that to get very good at any particular thing it’s best to give yourself to that thing, and to do so over and over again. My own experience, though, is that working in one genre strengthens the other as well. Then, of course, there really is the very real issue of making a living at it, difficult but possible as a fiction-writer, and completely impossible as a poet. I’ve been wondering lately, if I could remove that very glaring discrepancy, would I still focus on fiction next. I think I would, but I can’t say for certain.

I: Apart from the obvious (which is time constraints, those of both of us being why I’m sending this last block of questions at once now), do you anticipate that having become a mother will alter how you write and what you write about when you once again sit down at an empty page?

AP: I think it will, in the clichéd ways that everyone told me it would, and that I could not honestly have imagined before becoming a parent. By which to say, my heart is more open. I know the interconnectedness of the world in a way that used to be intellectual and is now entirely visceral. Being continually in the presence of someone very vulnerable, I’m more attuned to vulnerability of people both real and imagined (ie; characters). The novels that I’ve loved recently—Room by Emma Donoghue, The Road by Cormac MacCarthy, Dog Boy by Eva Hornung—are all at core about the profound attachment between parent and child. I don’t know what I’ll write when I come back to fiction, but at this stage a parent and child dynamic seems appealing to explore. Finally, on a pragmatic level, becoming a mother has already made me more focused. No more with the hours and hours wasted on Facebook—or, at least, when I waste them, the regret is greater and the writing suffers more.

I: I’ve long felt like I shouldn’t ask writers about their experiences as mothers, because male writers never get similar questions about fatherhood. But I’m changing my mind about this, because I’m really interested to know more about artists who are mothers, and certainly parenthood is one of those male/female experiences that don’t necessarily run parallel anyway. Do you think such questions are relevant?

AP: Being so new to motherhood, I’m always curious about the same thing. Everyone seems to say something different: some that mothering made them better writers (for some of the reasons mentioned above), and others that it has landed them in a perpetual domestic quagmire that seriously hampers them artistically. I’ve already experienced both extremes, and I imagine I’ll fluctuate back and forth between them for the duration of my writing and mothering life. Anyway, in answer to your question, and despite the fact that I’m still wondering about this one myself, yes, I think it’s a very relevant question, and will continue to be so as long as there are men and woman and art.

AP: Being so new to motherhood, I’m always curious about the same thing. Everyone seems to say something different: some that mothering made them better writers (for some of the reasons mentioned above), and others that it has landed them in a perpetual domestic quagmire that seriously hampers them artistically. I’ve already experienced both extremes, and I imagine I’ll fluctuate back and forth between them for the duration of my writing and mothering life. Anyway, in answer to your question, and despite the fact that I’m still wondering about this one myself, yes, I think it’s a very relevant question, and will continue to be so as long as there are men and woman and art.

I: What writers have inspired you to become the writer you are today?

AP: Jack Gilbert, Charles Wright, Bronwen Wallace, Jane Mead, Jane Hirshfield, Jane Kenyon (a pattern emerges!), Susan Minot, Tolstoy, Tsvetaeva.

I: What are your favourite books?

AP: Currently: Anna Karenina, The Road, The Great Fires, Room, Dog Boy, Given Sugar Given Salt.

I: What are you reading right now?

AP: A Spell of Winter by Helen Dunmore, Freedom by Jonathan Franzen (actually, I’m listening to it—somewhat begrudgingly—in the car), and various (largely disappointing) books about how to get my child to sleep without pretending she isn’t there.

Artists’ babies don’t sleep either! And we are all foolish enough to turn to books. (Of course as writers when must feel extra dissapointed because if the books don’t help us who can?)

Great interview Kerry.