May 21, 2008

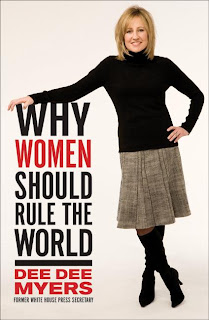

Why Women Should Rule the World by Dee Dee Myers

I decided I had to read Why Women Should Rule the World after I heard Dee Dee Myers interviewed on CBC’s The Current last month. Her intelligence and experience made a remarkable impression, but it was her optimism that was so inspiring. Coupled with the absolute sensibility of her message: that empowering women is good for everybody. The title is provocative but Myers means it, defining world-ruling as “[taking] advantage of all that each of us has to offer.”

I decided I had to read Why Women Should Rule the World after I heard Dee Dee Myers interviewed on CBC’s The Current last month. Her intelligence and experience made a remarkable impression, but it was her optimism that was so inspiring. Coupled with the absolute sensibility of her message: that empowering women is good for everybody. The title is provocative but Myers means it, defining world-ruling as “[taking] advantage of all that each of us has to offer.”

This book’s strength is its fusion of disparate ideas to form a comprehensive whole– so refreshing. Part of it is the politically sensitive nature of Myers’ material– she’s doing a lot of elaborate sidesteps on the way towards her arguments, in order not to be read as in attack mode.

But more than sidestepping, Myers articulates her ideas well beyond polemics. Part of this is her book’s hybrid nature: part memoir, part treatise. She is able to illustrate her own experiences in politics, the ways in which being a woman hindered her own advancement– as White House Press secretary she was given more responsibility than authority, which seems to be a typical story; how she was told, when she protested a subordinate colleague being paid a higher salary, that he had a family to support; the struggle to be likable in authority, which men are rarely faced with. Myers worked as Press Secretary in the Clinton White House for two years, worked in writing and television afterwards, and then got married and had a family.

She writes, “That’s my story, but…” The “but” being key, that hers is not the only choice. “Women want and deserve not only the flexibility to manage work (and family) from day to day, but also the ability to make choices that allow them to pursue their goals across a lifetime.” Her focus remains on power, however, because “[a]ssuming that women– even women with children– don’t want the top jobs means that too many women will never get the chance to make those important decisions for themselves.”

Myers’ reality is complex, and she asserts that women need to accept and support women whose choices are different from their own. She thinks of herself as a feminist, but from watching her son and her daughter she’s certain– “[it] isn’t nature or nurture: It’s both.” She acknowledges aggressive tendencies inherent in men in particular, but realizes these inherited traits aren’t our destiny. Dealing with the example of Margaret Thatcher: that it is too much to expect one woman to change everything, and surely her position altered the world’s opinion of what women were capable of.

That different can be equal: “That doesn’t mean that every man should be expected to behave one way, nor every woman another. Rather it means that women’s ideas and opinions and experiences should be taken as seriously as men’s– regardless of whether they conform to traditional stereotypes.”

Through her own experiences, statistics, and interviews with other women, Myers illustrates the various ways women can be systemically excluded from power. Showing that this is dangerous, not just in principal, but in terms of economics: she shows women as “the engine driving economic growth worldwide,” and not just with their immense consumer power, as she cites studies showing that Fortune 500 companies with the highest percentage of women on their boards have significantly higher returns on equity, sales and invested capital.

Myers explains that men and women experience the world differently, and she demonstrates how traits typical to women, such as negotiation skills and collaborative strengths, can be highly effective in business. Moreover that women’s own lives are strong training grounds for management experience– motherhood in particular. She cites examples of women playing key roles in peace processes around the world. That in achieving “critical mass”– wherein women are not token, but a strong enough force to actually make a difference– everybody wins.

Myers is not overtly prescriptive– the general nature of her arguments ensures her book’s relevance is wide. Surely different institutions must find their own way towards solution, by Myers’s book is undeniable impetus for them to do so. I would like to think a man would read this, and find it as fascinating as I did– and not get defensive. That women could cease slinging internecine arrows for a little while, and understand that ganging up on each other is part of a game we don’t have to keep playing. The world can be better.

“This isn’t what I think,” writes Myers. “It’s what I know.”