October 8, 2015

Really Fun DIY Autumn Craft

A few trees on our street have gone all autumnal, and while the world is not yet awash in golden and orange, the few trees that have turned already have got us in an autumn spirit. Iris had fun playing peek-a-boo with some of them on her way home from school today, and we’re glad she was not picked up by the Ministry of Flagrant Racism and Canadian Values for daring to hide her face no matter how patriotic her covering.

A few trees on our street have gone all autumnal, and while the world is not yet awash in golden and orange, the few trees that have turned already have got us in an autumn spirit. Iris had fun playing peek-a-boo with some of them on her way home from school today, and we’re glad she was not picked up by the Ministry of Flagrant Racism and Canadian Values for daring to hide her face no matter how patriotic her covering.

(Halloween is coming. If our government is still in office then, what are they going to do?)

And so we were inspired to partake in an autumn craft this evening for our weekly Fun Night, which is a dinner-hour activity that allows us to hang out and play together for a little while, instead of the rush-rush-rushing that is our regular weeknight routine. I’ve included step-by-step instructions below so you can play along too!

- See a link to a DIY Autumn Leaf Bunting tutorial posted on Facebook, and because you have a thing for bunting, actually consider doing it. Even though you hate doing crafts. The site it’s from is called The Artful Parent, but you’re more of an abstract artful parent, if you’re remotely artful, which you’re not.

- Gather leaves on the walk home from school. Feel smug and sanctimonious, anticipating the excellent time you’re going to be spending with your family and anticipate the reactions you’ll receive when you post your DIY Bunting on Facebook. Contemplate making strands upon strands of the stuff, and bringing them to Thanksgiving gatherings all weekend long so that people will admire your creativity and quirky bunting ways.

- Feel extra wonderful because you even let your kids pick up leaves that were kind of gross and had spots on them. Because it’s about them, really. And my, what a terrific childhood you’re providing them with…

- Buy store-brand wax paper at the grocery store.

- And now it’s time! You’ve already made cranberry brie chicken pizza for dinner that made the children cry (although this was before they tried it; they conceded it was delicious in the end) and so you’re on a roll.

- Press the leaves between two pieces of wax paper. The child who is still upset about the pizza gets upset again because she wants matching colours for each piece of bunting, but you want to mix it up like a rainbow. You’re really fucking insistent about this.

- (Read through the instructions for the bunting at The Artful Parent and realize that the Artful Parent actually made HER DIY autumn bunting while her child was at school.)

- Your husband pulls out the iron. Your children have never seen one. They marvel at this shiny and new piece of technology.

- He begins to iron. It should take a few minutes, the instructions say, for something to happen. Nothing happens. So he turns up the temperature. He starts to iron like no one has ever ironed before. Eventually you realize he is about to iron a hole right through your kitchen table. The leaves are burnt to a crisp. The wax still hasn’t melted. The leaves aren’t pretty anymore.

- This is the point when you storm off and start googling “Why won’t my wax paper melt?” This doesn’t actually seem to be something that happens to many people. You get sucked into a hole of websites about weird ways to preserve leaves and really stupid things that people do with them. You wonder what the point of anything is. You are suffering from bunting grief. It’s terrible.

- This is the least fun Fun Night on record.

- Back in the kitchen, however, your husband has saved the day. He’s poured out glue and everybody’s slapping the non-burnt leaves onto paper. “But what’s the point of this?” you ask him. “What’s the point of bunting?” is his retort, which is blasphemous, but still. And gluing leaves onto paper looks like of fun, so you join in.

- The night is saved by your husband’s excellent improvisational skills. And red wine.

October 7, 2015

No wonder the children grew peaky

“So he didn’t have your advantages,” went on Homily breathlessly, “and just because the Harpsichords lived in the drawing room—they moved in there, in 1837, to a hole in the wainscot just behind where the harpsichord used to stand, if ever there was one, which I doubt—and were really a family called Linen-Press or some such name and changed it to Harpsichord—”

“So he didn’t have your advantages,” went on Homily breathlessly, “and just because the Harpsichords lived in the drawing room—they moved in there, in 1837, to a hole in the wainscot just behind where the harpsichord used to stand, if ever there was one, which I doubt—and were really a family called Linen-Press or some such name and changed it to Harpsichord—”

“What did they live on,” asked Arietty, “in the drawing room?”

“Afternoon tea,” said Homily, “nothing but afternoon tea. No wonder the children grew up peaky. Of course in the old days it was better—muffins and crumpets and such, and good rich cakes and jams and jellies, And there was an old Harpsichord who could remember sillabub of an evening. But they had to do their borrowings in such a rush, poor things. On wet days, when the human beings sat all afternoon in the drawing room, the tea would be brought in and taken away again without a chance of the Harpsichords getting near it—and on fine days it might be taken out into the garden. Lupy has told me that, sometimes, there were days and days when they lived on crumbs and water out of the flower vases. So you can’t be too hard on them; their only comfort, poor things, was to show off a bit and wear evening dress and talk like ladies and gentlemen…” —Mary Norton, The Borrowers

(We’re reading this right now and I’m loving it so much. I don’t know that I’ve ever read it before. When I was a child, I was into the American knockoff, The Littles, but I had no taste, and Mary Norton is so clever, funny and bright. I also like our copy because the cover is by Marla Frazee, who is one of my favourites. And sort of related, we recently finished reading The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, which went over very well, except that Iris now walks around saying apropos of nothing, “Aslan die?” and I don’t think she knows what die means, or even Aslan for that matter. But Harriet is quite enchanted and now we’re going to read the whole series, and tonight we were reading a new book called Written and Drawn by Henrietta, by TOON Books, and there was a Narnia reference, and I haven’t seen Harriet that excited since she found out she had a wobbly tooth.)

October 7, 2015

Rereading Anne’s House of Dreams

I’ve been reading the Anne books as long as I’ve known how to read, though my preferences among them are a bit curious as Anne aficionados go. Anne’s House of Dreams was always my favourite, followed by Anne of Ingleside, because I found her children incredibly amusing. Rainbow Valley I could take or leave, but of course I loved Rilla of Ingleside, which seemed a proper grown-up book. Anne of Ingleside didn’t particularly, however, but it did permit glimpses inside Anne’s marriage, which I was fascinated by. (“They sleep in different bedrooms,” I said to my mother one summer day at the locks at the Rosedale Canal. We were with family friends. “So how did they manage to make babies?” I was told we’d talk about it later.) Anne of Ingleside is the one book of all my Anne book whose binding has completely come apart, which isn’t that surprising considering it was a crappy Seal paperback (and oh, good gracious, the typos! The typos!), although the others are holding up okay. It is possible that I have never reread Anne of Avonlea or Anne of the Island. Grown-up Anne was always more interesting to me than her youthful counterpart, although I’ve reread Anne of Green Gables twice in the last ten years and it’s only deepened my appreciation for its goodness and depth.

I’ve been reading the Anne books as long as I’ve known how to read, though my preferences among them are a bit curious as Anne aficionados go. Anne’s House of Dreams was always my favourite, followed by Anne of Ingleside, because I found her children incredibly amusing. Rainbow Valley I could take or leave, but of course I loved Rilla of Ingleside, which seemed a proper grown-up book. Anne of Ingleside didn’t particularly, however, but it did permit glimpses inside Anne’s marriage, which I was fascinated by. (“They sleep in different bedrooms,” I said to my mother one summer day at the locks at the Rosedale Canal. We were with family friends. “So how did they manage to make babies?” I was told we’d talk about it later.) Anne of Ingleside is the one book of all my Anne book whose binding has completely come apart, which isn’t that surprising considering it was a crappy Seal paperback (and oh, good gracious, the typos! The typos!), although the others are holding up okay. It is possible that I have never reread Anne of Avonlea or Anne of the Island. Grown-up Anne was always more interesting to me than her youthful counterpart, although I’ve reread Anne of Green Gables twice in the last ten years and it’s only deepened my appreciation for its goodness and depth.

And so last week I turned again to House of Dreams, because we’re reading it for our book club. And I was a bit surprised to find that reading it was nothing but a pleasure, and it was rich with humour and surprises. And both, in the case of the regular references to suicide by Miss Cornelia Bryant: “Doctor Dave hadn’t much tact, to be sure—he was always talking of ropes in houses where someone had hanged himself.” There’s a lot of dark humour in the book, and darkness full stop in regards to poverty and status of women in the village families. Anne and Gilbert’s home stands in contrast to to the world around them, just like Captain Jim’s light house.

And yes, Captain Jim, the one bit I was just not as taken by. He was a bit like an idiot savant and I kept wondering about his sexlessness. I wondered a lot about sex in general, actually, and have a better understanding of why fan fiction was invented because I would actually like to read Anne and Gilbert porn—wouldn’t you? Anyway, I was relieved when LM dialled it back whenever I fear that he was about to launch into a sea yarn. There is no book I’d ever want to read less than Captain Jim’s life book, and while I didn’t feel relief, exactly, when he crosses the bar, I wasn’t worry to see the last of him.

The book I do want to read is this one though, about Anne and Gilbert’s first year of marriage. About Anne’s longing for motherhood, which is a subtle but persistent force throughout the book (and even violently so on the part of her friend, Leslie Moore). It goes unspoken, but it’s remarkable that in having a child, Anne would meet a blood relative for the very first time, which even in a world lousy with kindred spirits has to mean something. At the beginning of the book she witnesses Diana holding her own daughter:

“cuddling Small Anne Cordelia with the inimitable gesture of motherhood which always sent through Anne’s heart, filled with sweet unuttered dreams and hopes, a thrill that was half pure pleasure and half a strange ethereal pain.”

The beginning of the book is wonderful, a homecoming to Avonlea, Anne and Gilbert’s wedding the first Green Gables has ever seen. The prose is still so familiar to me from when I read it years and years ago, and I can anticipate each next line as I encounter it: the bit about the bird that sang during the ceremony. Marilla is stiff and deadpan, and Mrs. Rachel Lynde is still every bit herself, and we’re acquainted with characters from previous books (although not Windy Poplars, which was published after House of Dreams, although it takes place before, making it seem as though her friends from Summerside did not making the guest list).

They move to Four Winds Harbour, near the village of Glen St. Mary. There they meet the neuter seafaring Captain Jim, and Miss Cornelia Bryant in her ostentatious wraps and declarations of, “Isn’t it just like a man?” And Leslie Moore, whose name I always found so euphonic, and quite fitting that her husband was called Dick. Indeed. Tragic Leslie, who hates Anne for her fortune as much as she admires her as a friend, and Montgomery’s acknowledgement of that complexity in female relationships is really quite profound. I also rejoiced at the birth of Bertie Shakespeare Drew, who would come to be an important character in the following book.

I always found the romance between Anne and Gilbert most endearing, and I imagine that my greatest attraction reading the book when I was young was imagining that somebody might love me as much as Gilbert loves Anne. This is also why, while I am lucky that somebody loves me much indeed today. I often admonish him for not voicing his interior monologue using phrases like, “I can hardly believe that you are mine.” (My husband believes I am his too much entirely. Poor man.) It is possible that Gilbert Blythe gave me an entirely unrealistic standard of courtly love.

I don’t recall being disappointed by the Anne in Anne’s House of Dreams, though I can certainly see why one would be and I really liked Sarah Emsley’s post about Anne’s dismissal of her writing talents in the novel. Kate Sutherland (who, lucky us, is in our book club!) address this too in a post a few years ago, suggesting that Anne had not let herself down so much as readers had misidentified her as a writer. She had had other goals for herself, although yes, it would have been nice if literature proper in the novel wasn’t so gendered. And while Anne does go the route of plucky childhood heroines and settles down into conventionality ala Laura Ingalls, Dorothy Ellen Palmer made a great point on Facebook about the importance of seeing Anne as an adopted child whose spiritedness may have been a way to deal with trauma, loss and insecurity, and that the trajectory of this character to a happy and stable adult, wife and mother, is incredibly remarkable. (See also: Alison Kinney’s essay, “The Uses of Orphans.”)

What has always been most striking to me about the book is Mongomery’s depiction of the stillbirth of Anne’s first baby, this indefatigable character overcome by heartbreak, and her pain is so real. The experience was close to its author’s heart, giving an extra layer of poignance to the narrative, as well as authenticity. Striking too is Marilla’s fear at the loss of her own daughter, and her relief when Anne’s life is saved. Her inability to articulate her emotions too: “‘Time will help you,” said Marilla, who was racked with sympathy but could never learn to express it in other than age-worn formulas.” And Leslie Moore who dares to say, “I envy Anne… and I’d envy her even if she had died! She was a mother for one beautiful day. I’d gladly give my life for that!” Which is neither kind nor wise but something beyond either. Anne’s anger as well at the idea her daughter was in “a better place.” And when she’s told that one day it will hurt less and she replies, “The thought that it may stop hurting sometimes hurts me worse than all else.”

Although the novel’s most heartbreaking part of all takes place when we learn in chapter 35 that Gilbert Blythe is an ardent Conservative—but of course, and so was Matthew, we remember. But then after 18 years, the Tories lose to a sweeping majority by the Grits, which does to show that anything can happen. Captain Jim himself redeemed by the fact that he wasn’t a Conservative himself—though he dies. Hopefully not a comeuppance, but I do hope that somehow Montgomery’s narrative is some kind of political forecast. More accurate than some polls, I am sure. It doesn’t have to be the Liberals necessarily, but please, in two weeks, let us be able to say, paraphrasing Captain Jim, “After nearly ten years of Tory mismanagement, this down-trodden country is going to have a chance at last.”

October 6, 2015

Canadian books for high school readers

This summer, I got one of the coolest gigs I’ve ever had, the opportunity to write a list of suggested Canadian fiction titles with which high school English teachers can freshen up their syllabus. As I write in the piece, I was inspired by Natalee Caple’s “Why I Teach Brand New CanLit,” which was about university classes, but her points were just as relevant for high school teachers as well. And it was no challenge to come up with the 25 titles I ultimately included in the list—I do suspect that teachers are actually spoiled for choice in this context, should they choose to be.

My list appears at Education Forum, which is the magazine of the Ontario Secondary School Teacher’s Federation. You can read it here.

October 4, 2015

Ledger of the Open Hand, by Leslie Vrydenhoek

“Great civilizations aren’t remembered for their tax policies.” —Marsha Lederman, The Globe and Mail.

I thought of Ledger of the Open Hand, by Leslie Vryenhoek, when I read the quote above, from a story about the failure of politicians in our federal election to grapple with issues deeper than budgets and surpluses, to talk about anything except money. Because Vryenhoek’s novel is about a character just like these uninspired (and uninspiring) politicians, Meriel-Claire Elgin who sees the world in terms of debits and credits, who conflates value with values, and the novel is also about how limited is such a worldview.

Though it’s an easy trap to fall into, this obsession with fiscal responsibility and thinking of thrift as a moral virtue. Raised in a small prairie town by parents of modest means, Meriel-Claire is determined to prove herself responsible as she begins university in the city, working in the summers and part-time to supplement her parents financial support. Though she quickly sees her experience in contrast with that of her sophisticated roommate, Daneen, who takes her family’s wealth for granted. Their respective financial situations seem to demarcate their places in the world, Meriel-Claire decides, imagining herself as the hard-working ant while her grasshopper friend devotes herself to shallow and frivolous concerns. Unconsciously seeing the fable analogy to its end, Meriel-Claire envisions a day when there will be justice, when her hard-work and prudence will be rewarded and Daneen will meet her inevitable downfall.

But of course, life is not this simple, structured like a ledger sheet (which, cleverly, is suggested in the novel’s cover image), and neither is the novel. Interestingly, the story of the ant and the grasshopper has alternate versions in which it’s the grasshopper who is actually the virtuous one, and The Ledger of the Open Hand (like life itself) permits plenty of space for such ambiguity. The novel is broad in its scope, taking place over three decades, and showing the changes in the life of Meriel-Claire (and in her family’s) as she moves from her twenties to her forties. And because all of this is presented from Meriel-Claire’s point of view, everything is about money—she starts off as a bookkeeper and eventually becomes a debt counsellor; with colleagues and family, she gains a fierce (and justified) reputation as a tightwad. Though Meriel-Claire doesn’t see it quite that way herself, and Vryenhoek gives us real sympathy for her situation and how she got there, and the truth is that so much about being in the world is about money after all. It’s just simpler for people like Daneen who don’t have to worry about it. Of course it’s easy not to think about money all the time when you have no need to.

Written in short chapters that whisk the reader through the years, we follow Meriel-Claire through her first jobs, home-ownership, through failed investments and unexpected windfalls. We see her parents sell their business and begin to enjoy their retirement, and live a life that seems at odds with Meriel-Claire’s memories of her modest upbringing. Their distance from their daughter is augmented by tragedy in their lives, tragedy that none of them is really ever able to account for. And looking on through all of this is Daneen, who grows close to the family and eventually becomes a successful author whose stories seem a bit too familiar to Meriel-Claire, raising issues of just how much borrowing is permitted in matters of story as well as money, and also of how adept is anybody at seeing a reflection of her own self?

While all too present on the political stump, issues of finance are curiously absent from so much of literature, whose bills seems to get paid almost by magic (unless it’s a book about the farm and foreclosure). Vryenhoek manages to weave a deep and engaging novel out of money matters, though she makes it about more than that. While at times Meriel-Claire is a bit robotic in her approach to the world and Daneen can verge on caricature, Mariel-Claire’s parents are rich, complex and fascinating characters, and the connections between all these people over the decades yield surprising insights and remarkable depth, culminating in a really wonderful story. Vryenhoak’s prose is bright and accessible, the novel fast-paced and compelling, and there is a startling originality to all of it.

October 1, 2015

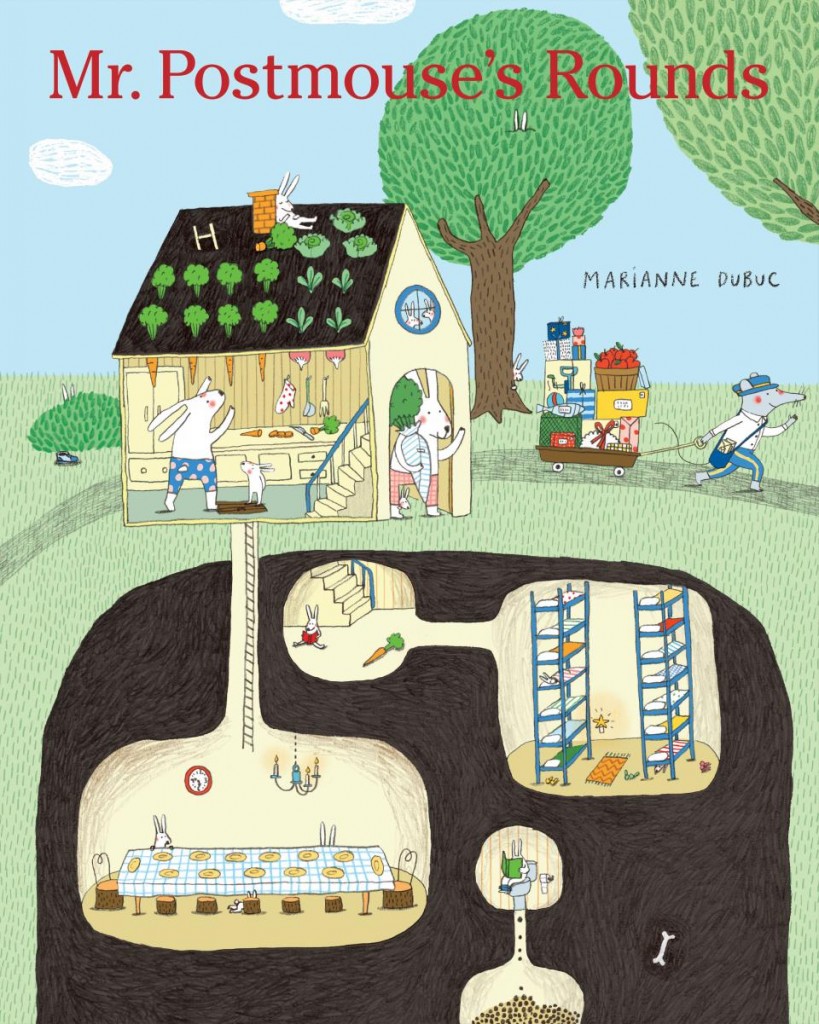

Mr. Postmouse’s Rounds by Marianne Dubuc

We are a little bit crazy for Marianne Dubuc in our house, which is interesting because she does something very different with every book she writes, but what all her books have in common are elements of whimsy, unabashed absurdity, rewards for those who are attentive to detail, and an all-engaging strangeness. And in Mr. Postmouse’s Rounds, she has written a book about the mail, and so naturally I am totally obsessed. As are my kids, because, well, look right there on the cover: there is a rabbit pooing. Sitting on the toilet reading, no less. And this glimpse into the rabbits’ hidden world is what’s so entrancing about this book, exploring these animal abodes that Dubuc has dreamed up: the bear’s house has honey on tap from a hive on the roof; the snake’s long skinny house is outfitted with heat lamps; the squirrel’s got a clothesline and sleeps in a hammock; the mole house has a kettle on the stove.

It’s the kind of book a kid can read with her finger, tracing along the Postmouse’s route and in and out of the houses he delivers to. While the illustration style is very different, we love it for the same reasons I loved Jill Barclay’s Brambly Hedge books when I was little, tiny worlds magnified, access into hidden corners, such incredible attention to detail. And yes, it’s funny. There’s the poo (and the flies’ house is actually a giant piece of much poo, much to everybody’s delight). And there are abandoned shoes, mitts and candy wrappers littering the animals’ neighbourhood, and just what’s going on in each of these dwellings? Each house containing a story of its own, so that you can read Mr. Postmouse’s Rounds over and over again and—which I know from experience—the young reader will continue to keep exploring its pages long after the reading is done.

October 1, 2015

The Possibility of Elephants

“I had a job at Pizza Hut in the last years of the old century, the location on Toronto’s Bloor Street just west of Avenue Road. I worked the take-out counter, serving ancient slices that were sweating under the heat-lamps, and one day I looked up from the till to see an elephant lumbering by, a bright emerald ribbon secured to its tail…”

“I had a job at Pizza Hut in the last years of the old century, the location on Toronto’s Bloor Street just west of Avenue Road. I worked the take-out counter, serving ancient slices that were sweating under the heat-lamps, and one day I looked up from the till to see an elephant lumbering by, a bright emerald ribbon secured to its tail…”

And so begins my essay on rereading Ann-Marie MacDonald’s Adult Onset, which is also about the mutability of memory, of literature, and of streetscapes, Bloor Street’s in particular. It’s about Balloon King, Starbucks, mistakes in fiction, parallel universes, and the Shafia family murders. It’s about Honest Eds and trauma, Daniel Libeskind’s “Crystal” and Jian Ghomeshi’s creepy voice. Plus, about having a two year old.

Anyway, I am really proud of it. As many of you already know, the word “essay” comes from the French verb “to try” and for me this piece was certainly an experiment. But I am very pleased with how it turned out, and grateful for Rohan Maitzen and her colleagues at Open Letters Monthly for their work on the piece, and for giving it such a wonderful home.

September 29, 2015

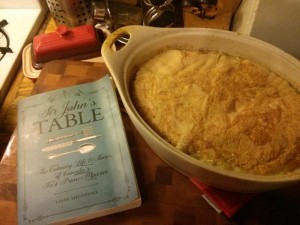

Sir John’s Table, by Lindy Mechefske

I could never be a food blogger for all kinds of reasons, one of which is that all my pots and serving dishes are indelibly stained and my kitchen is old and grubby (and poorly lit). The other important reason is that I tend to interpret recipes as general guidelines instead of instructions, but in the case of the new book, Sir John’s Table, by Lindy Mechefske, this turned out to be an advantage. It meant I was unafraid to take on the recipe for Sir John A’s Pudding from a cookbook from the 1880s, a recipe named in honour of the first Prime Minister of Canada, whose instructions included “size of an egg” for butter portioning, no word on what vessel to cook it in, and vague baking instructions as follows: “Bake in oven for a few minutes.”

I could never be a food blogger for all kinds of reasons, one of which is that all my pots and serving dishes are indelibly stained and my kitchen is old and grubby (and poorly lit). The other important reason is that I tend to interpret recipes as general guidelines instead of instructions, but in the case of the new book, Sir John’s Table, by Lindy Mechefske, this turned out to be an advantage. It meant I was unafraid to take on the recipe for Sir John A’s Pudding from a cookbook from the 1880s, a recipe named in honour of the first Prime Minister of Canada, whose instructions included “size of an egg” for butter portioning, no word on what vessel to cook it in, and vague baking instructions as follows: “Bake in oven for a few minutes.”

We really weren’t sure. “This is an experiment,” I kept telling my family, and then asking them, “Isn’t living with me a glorious adventure?” No one answered. They were all a bit irritated that our main course had been roast cauliflower. “I bet none of your friends are having pudding tonight in honour of Canada’s first Prime Minister,” I told Harriet. She looked at me funny: “Mom, do we have any ice cream?”

Sir John A’s Pudding is from Dora’s Cook Book, by Dora E. Fairfield, published in 1888—one known copy is still publicly available. It is a bread pudding, the bottom made with bread crumbs, egg yolks and lots of milk. Spread on top are stiff egg whites and sugar. I baked the whole thing in the oven for much longer than a few minutes (though I can’t remember how long now—I am as bad as Dora). When it came out of the oven, the topping was nicely browned but the pudding still seemed a little gloopy (“But gloopy means delicious, right?” I asked. Nobody cheered.) However once it had been resting for a little while the pudding was set, and now it was finally time to dish it up and assess the damage.

Sir John A’s Pudding is from Dora’s Cook Book, by Dora E. Fairfield, published in 1888—one known copy is still publicly available. It is a bread pudding, the bottom made with bread crumbs, egg yolks and lots of milk. Spread on top are stiff egg whites and sugar. I baked the whole thing in the oven for much longer than a few minutes (though I can’t remember how long now—I am as bad as Dora). When it came out of the oven, the topping was nicely browned but the pudding still seemed a little gloopy (“But gloopy means delicious, right?” I asked. Nobody cheered.) However once it had been resting for a little while the pudding was set, and now it was finally time to dish it up and assess the damage.

Guess what: it was totally divine. And everyone conceded that living with me was an adventure after all, a most delicious one. I did my I’m always right dance. I always mostly am.

Though not, admittedly, with my immediate assessment of Mechefske’s book. Sir John’s Table: A Culinary Life and Times of Canada’s First Prime Minister as a concept did not seem at first compelling to me, but then I opened it up and started reading. And what I found was an engaging, light and fun and informative text. So engaging, yes, that it led me to attempt archaic heritage recipes, plus the book is also a really interesting biography of Canada’s first Prime Minister.

Since we’re going all Full Disclosure in this post, I will reveal to you that I’ve not watched any political debates during this current federal election. As these debates fail the Bechtel Test on every discernible level, are intellectually stupefying AND we don’t have TV, I’ve felt more comfortable getting my political information from newspapers instead. There is something about the absence of women’s voices and the general feeling that anything concerning women’s experiences is mere frippery that renders most politics (and political biographies) null and void to me. It’s grown-ups acting out playground games, and taking themselves far too seriously. It’s just inherently uninteresting.

Since we’re going all Full Disclosure in this post, I will reveal to you that I’ve not watched any political debates during this current federal election. As these debates fail the Bechtel Test on every discernible level, are intellectually stupefying AND we don’t have TV, I’ve felt more comfortable getting my political information from newspapers instead. There is something about the absence of women’s voices and the general feeling that anything concerning women’s experiences is mere frippery that renders most politics (and political biographies) null and void to me. It’s grown-ups acting out playground games, and taking themselves far too seriously. It’s just inherently uninteresting.

Which is not to say that political biographies must necessarily contain a recipe for bread pudding, or that the domestic is anymore inherently a female purlieu, but it certainly was in the 19th century. Which means that “culinary life and times” of Sir John A. Macdonald is going to give special attention to the women in his life and the personal and political roles they played: his mother, his wives, his lifelong friend who was also a pub owner. We learn about the food (bannock!) his mother brought to feed her family on the long voyage from Scotland to Canada. Also about Macdonald’s favourite childhood desserts, how traditional British foods were adapted to North America, wedding cakes from the 1860s, mourning rituals (after the death of his first wife), how the picnics at which he made his famous stump speeches would have been catered (by Mrs. Beeton, at least), and just how a roast duck dinner managed to save the Dominion after all.

For a light book, Mechefske manages to be rigorous about colonial atrocities, juxtaposing a lavish Toronto dinner with Metis and First Nations people starving on the plains at the same time. Her story of the triumph of Sir John A’s railroad also includes a legacy of racism and exploitation of the Chinese workers who built it. She manages to balance her portrayal of the generous and charismatic Macdonald with the dark side of his legacy—also his own propensity for problems with drink: “He joined the Temperance Society again,” is a sentence that pops up more than once.

My one criticism is that the recipes have not been adapted for modern cooks, and so are more a curiosity than something the reader can use. Although there is value too in these heritage recipes reprinted as they were, for what they tell us about how 19th century cooks did their work, how ingredients, measurements and cooking methods were different, and also the peculiar stylistic quirks of their writers. And my own experience certainly shows (who knew?!) that the intrepid 21st century cook can have success with these recipes all the same.

September 27, 2015

Fishbowl, by Bradley Somer

It’s true what you might have heard about Bradley Somer’s Fishbowl being a novel that actually chronicles a goldfish’s plummet from the twenty-seventh floor balcony of a high rise apartment building. (I heard my first raves about this book from the Parnassus Books blog.) And yes, the goldfish parts of the novel are actually from the fish’s point of view: at one point, one eye is skyward, and the other is focussed on the ground—what must the world look like like that?; his brain is too limited for a train of thought—it’s more like a handcar. Yes, the fish’s name is name is Ian. And it’s also true what you might have heard about Fishbowl if the thing you’ve heard is that it’s great.

It’s true what you might have heard about Bradley Somer’s Fishbowl being a novel that actually chronicles a goldfish’s plummet from the twenty-seventh floor balcony of a high rise apartment building. (I heard my first raves about this book from the Parnassus Books blog.) And yes, the goldfish parts of the novel are actually from the fish’s point of view: at one point, one eye is skyward, and the other is focussed on the ground—what must the world look like like that?; his brain is too limited for a train of thought—it’s more like a handcar. Yes, the fish’s name is name is Ian. And it’s also true what you might have heard about Fishbowl if the thing you’ve heard is that it’s great.

The structure of fishbowl is similar to the apartment building that is its setting, each unit home to its own story, stories stacked on top of stories. Common spaces are spare, unremarkable. Nobody lingers there. For each character it’s easy to imagine that he or she is alone in the world, to disregard the sound of footsteps overhead. But one day when the elevator breaks down, the illusion is shattered. Suddenly lives are intersecting in curious, irrevocable ways. A baby is about to be born. An old man has died. A cheating lover is about to meet his comeuppance. A lonely burly crossdressing construction worker is about to feel more beautiful than he’s ever felt before. And Ian the goldfish is about to be launched upon the ride of his life.

Eschewing a linear narrative for something more like a fish’s grasp of eternity, the novel takes place over a half hour or so, moving back and forth within that span of time (and sometime telescoping omnisciently into a distant future) to examine the period from a variety of points of view. For those ascending the building’s staircase—the elevator is broken, remember—time moves in slow motion, ploddingly, exhaustingly. For the lying cheat upstairs who is hurriedly ridding his bachelor suite of all signs of debauchery, time moves much too fast, not enough of it to allow him to clear away the evidence. For the woman whose baby is coming, everything is happening much too quickly, but also taking forever. And when she finally manages to reach her boyfriend at the pub, he tells her that he’ll be there—after one more round.

Fishbowl is a novel about relativity and relationships, and infinite interconnectedness of things. It’s also funny, absorbing, poignant, rich with twists and surprises, smartly plotted, deep and intelligent. And heartwarming—if you’re into that kind of thing. Underlining that although a person might be lonely, she is never really alone.

September 25, 2015

A Veritable Marathon

This morning I had the pleasure of dropping my children off at their respective schools, and then heading over to Victoria College to pre-drink for the book sale which started at 10am. By which I mean that I ordered a chocolate croissant and a cup of tea at Ned’s Cafe, and indulged in all of it—the food, the time, the solitude, the book sale anticipation. Thinking also about the extraordinary kindness with which people have responded to my previous blog post, and how it has caused all kinds of people special to me but far flung to get in touch after ages, and the whole thing has all been wonderfully buoying. I wasn’t expecting that. I just needed to get the words out, all 2000 of them, which took and hour and a half the other night, but it was time well spent, I can now say. As was this morning, the pleasure of my own company. I have adjusted extraordinarily well to having my mornings free (of the children, I mean; my mornings are generally full of work—I worked extra hard this week so that today I wouldn’t have to). The whole arrangement is so good, I feel like it should be illegal.

This morning I had the pleasure of dropping my children off at their respective schools, and then heading over to Victoria College to pre-drink for the book sale which started at 10am. By which I mean that I ordered a chocolate croissant and a cup of tea at Ned’s Cafe, and indulged in all of it—the food, the time, the solitude, the book sale anticipation. Thinking also about the extraordinary kindness with which people have responded to my previous blog post, and how it has caused all kinds of people special to me but far flung to get in touch after ages, and the whole thing has all been wonderfully buoying. I wasn’t expecting that. I just needed to get the words out, all 2000 of them, which took and hour and a half the other night, but it was time well spent, I can now say. As was this morning, the pleasure of my own company. I have adjusted extraordinarily well to having my mornings free (of the children, I mean; my mornings are generally full of work—I worked extra hard this week so that today I wouldn’t have to). The whole arrangement is so good, I feel like it should be illegal.

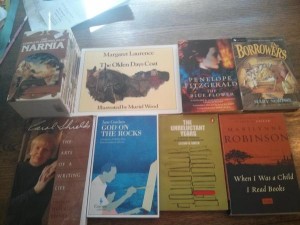

And the book sale? (BTW, this year they have a blog!) It was fantastic, and this is the first time I’ve not had to browse while toting a screaming baby. (Last year, whenever I turned a corner, someone would look up and say, “Oh, that was your baby crying.”) I’d intended to buy very few books, but it turns out that’s far simpler to accomplish when one is doing the toting a screaming baby thing. This year, alone, I managed to put down far more books that I picked up, but still came away with a sizeable pile, although nothing on years past. Complete Chronicles of Narnia—we’re halfway through The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe now, and we’re loving it. (Stuart and I, growing up on different continents, were both traumatized by the cartoon film version of this book as children, so have never really read the books.) So we look forward to reading the other books in the series. And also The Borrowers, and Margaret Laurence’s The Olden Days Coat to add to our Christmas Book library.

I picked up Carol Shields: The Art of a Writing Life, which I read about ten years ago but would like to read again. Marilynne Robinson’s When I Was a Child I Read Books, because Kate Sutherland handed it to me, and I generally follow her advice on most things. The Unreluctant Years: A Critical Approach to Children’s Literature, by Lillian H. Smith, famous Toronto children’s librarian who now has a library in her name. Published in the 1950s, I’m interested to see how this reads now—particularly now since I am an official children’s literature expert myself.

And finally, the novels. I walked around in the fiction section upstairs and was at one point holding a stack of ten books, which is lunacy because I have so many books to read already, I do not need to be gathering more. So I whittled my pile down to The Blue Flower, by Penelope Fitzgerald, and God On the Rocks, by Jane Gardam, both is excellent condition, and I feel very good about my choices.

Even with the tea and croissant, however, I find myself exhausted by the whole experience. One who has never lived it could not imagine how tiring it is to browse for books for two hours, pressure on the back, the shoulders, all that standing. Not to mention fighting for space with other browsers, elbow weaponry. Carrying the books around in the meantime. It’s a veritable marathon.

Thankfully I am an athlete in my prime.